The Messed Up Truth About The Tiananmen Square Massacre

When people rebel, authoritarian governments will try to crack down on them. The history of revolutions is filled with blood, as ordinary citizens have often faced hardship, censorship, and violence when they dare to speak truth to power. Despite this, people in countries across the world have continued to rise up, rebel, and stay vigilant.

Such was the case in China in 1989. The Tiananmen Square massacre, also known as the June 4th incident, was a horrific event wherein the government slaughtered thousands of protesting individuals in cold blood. Perhaps most horrifying of all, though, is that in mainland China, information regarding this mass murder has been suppressed for decades. For the rest of the world, one of the most potent of images the 20th century was that of the so-called "Tank Man," an unidentified Chinese individual who blocked a column of tanks during the protests, but not so in the country it happened. Here is the story of how the protests began, when martial law was declared, and the continuing impact of this historical atrocity on the present day.

The history of Tiananmen Square

Today, the words Tiananmen Square are synonymous with carnage. It wasn't always that way, however.

First constructed in 1651, according to Encyclopedia Britannica, the location takes its name from the massive stone Tiananmen — "gate of heavenly peace" — located inside its northern side, which had been constructed over two centuries earlier to separate it from the Forbidden City. Since then, Tiananmen Square has been a prized location in Chinese history, and today, the area is decorated by a number of monuments to events from the past: since 1958, for instance, the Monument to the People's Heroes fixture has stood in the center of the Square, and since 2003, the square's east side has been marked by the National Museum of China. Over to the west, then, there is the Great Hall of the People, an active political location wherein the National People's Congress meets annually, in a hall that seats 10,000.

A lot of history? For sure, but there's a rather large chunk that is missing: the two massive protests that occurred there, in the 20th century, are not referenced within the square itself. The first one, in 1919, was the outbreak of the May Fourth Movement. This rebellion was echoed 70 years later, in 1989, with a protest that has since been called the June 4th movement — and which, tragically, led to the military crackdown that still reverberates across the world today, and forever marred Tiananmen Square's reputation.

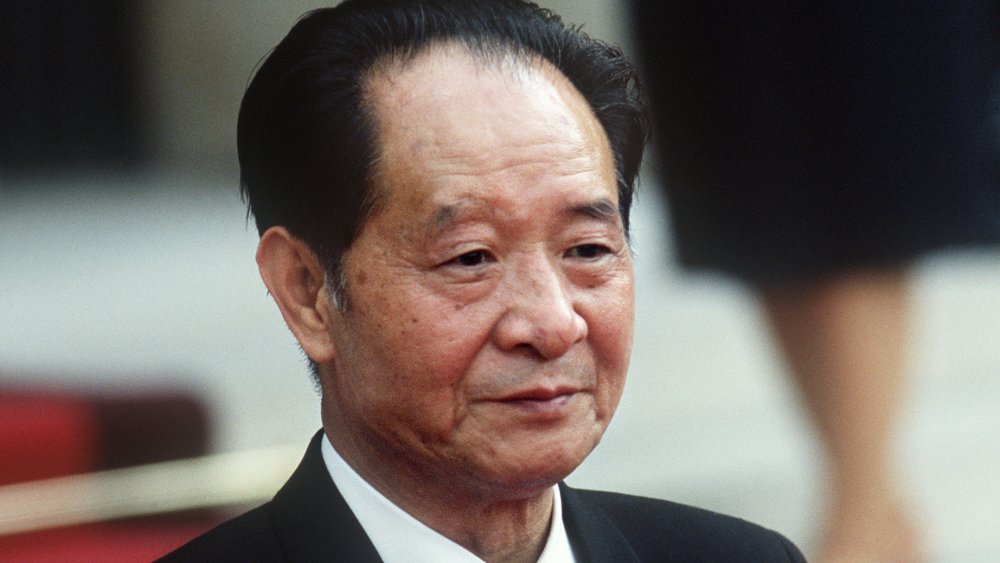

The death of Hu Yaobang triggered the protests

In 1989, the spark that ignited the powder keg was the death of Hu Yaobang (pictured), according to the Guardian, a Communist party official, and a leading member of the party's "liberal wing." Hu was beloved by the young and disenfranchised because of his advocacy for social and economic reforms, but this same record of progressiveness made him despised — and punished, via demotion — by his conservative enemies in government. Throughout the eighties, according to the South China Morning Post, Hu earned a reputation as a passionate liberalizer, striving to institute the sorts of democratic reforms that were being demanded by China's young, politically active student population. Hu, as a fierce critic of the Mao Zedong era, tried to dismantle the authoritarian power structures in place, introducing such measures as term limits, age limits, and collective leadership for government officials. Because of this, students considered him one of the few government officials who wasn't corrupt, and he only gained further accolades when he sought justice for the millions who had been persecuted under Mao's reign.

When Hu died of a heart attack at the age of 73, thousands of mourning students paid their respects by flooding Tiananmen Square, according to the Atlantic. Soon, this mass gathering became a mass protest against the government, whom had undermined Hu's efforts at every turn. As the days went on, these protesters put their collective boots down, and refused to leave Tiananmen Square.

The Tiananmen Square protests begin

To be clear, the protests at Tiananmen Square didn't come out of nowhere. Due to a combination of government corruption and income inequality, civil unrest had been brewing within the population for a long time, particularly among the youth. The death of Hu Yaobang was simply the moment where it all came together.

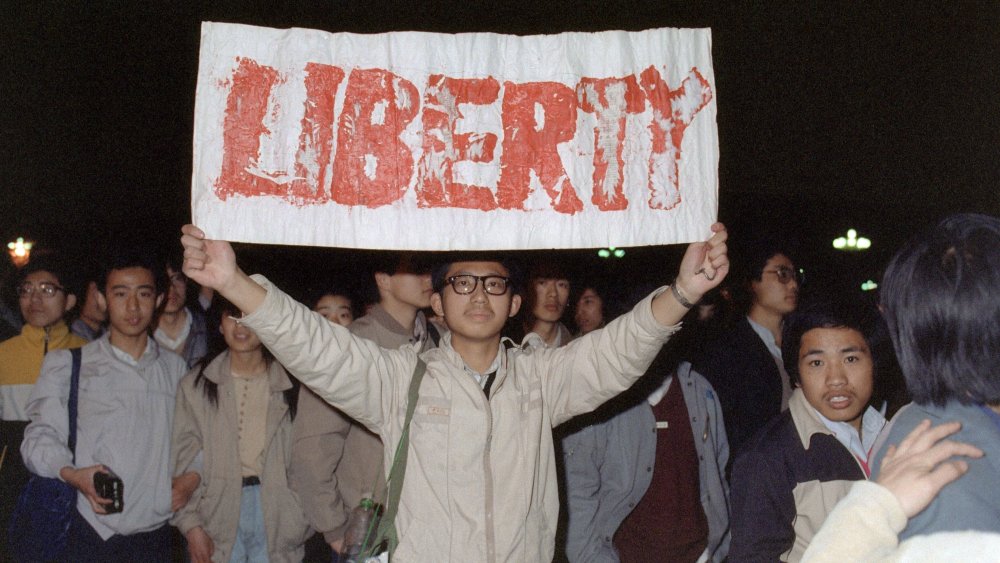

In the name of Hu Yaobang, according to PBS, these students demanded such reforms as a free press, more equal pay, fair housing, and other reasonable concerns which are similar enough to the problems that people are still protesting about in many countries today, the United States included. This also, for the record, was not an isolated group of protesters acting against the interests of the common people, despite government propaganda which claimed (and continues to claim) otherwise. This was a mass movement. Workers soon joined the students. By mid May of 1989, that the crowds gathering within Tiananmen Square had jumped from tens of thousands, to 100,000, to a mass of approximately 1.2 million. Classroom strikes followed. From there, Reuters reports, the movement only grew more powerful, as pro-democracy demonstrations soon took off in other parts of Beijing and the rest of China, as well.

By this point, the government was growing deeply concerned, with Premier Li Peng arguing that the protests needed to be "nipped in the bud."

The cry for change spreads outside Tiananmen Square

While Tiananmen Square was the focal point of these massive protests, it's important to recognize that the movement took hold all across the city, and not just among the student population (who, by this point, were not attending class anymore). As the protests grew exponentially, according to PBS, the people participating in them became increasingly diverse: Medical professionals, scientists, and even members of the Chinese Navy joined the fight for political reform, marching alongside the students. Old and young, industrial workers and police, the movement had grown to a point where 1 in 10 Beijing residents had joined in, clearly pitting the people against the government's top leaders.

The youth, though, continued to be the leaders of the movement. On April 22nd, 1989, over 100,000 university students gathered outside the Great Hall of the People, and demanded to meet with Premier Li Peng. Li did not answer their call. He was, around the same time period, working to convince the Party elder Deng Xiaoping that the students were trying to overthrow him, and that he needed to act decisively. This put Li and his faction in opposition with the minority faction of General Secretary Zhao Ziyang, who also wanted to curb the protests, but advocated for negotiation with the students rather than shutting them down.

Meanwhile, as April drew to a close, the foreign presses had zoomed in on the situation, and were covering it closely, much to the Chinese government's dismay.

The hunger strike

The protests slowed in the early days of May, according to PBS, as students returned to classes. However, the fire came roaring back to life on May 13th, with a mass hunger strike by 160 students, timed in anticipation of the historic visit of the Soviet Union's Mikhail Gorbachev.

Deng Xiaoping demanded that the students leave Tiananmen Square before Gorbachev arrived. They refused, pointing out that the government had refused to discuss reforms with them, and printed a manifesto that read: "The nation is in crisis — beset by rampant inflation, illegal dealing by profiteering officials, abuses of power, corrupt bureaucrats, the flight of good people to other countries and deterioration of law and order. Compatriots, fellow countrymen who cherish morality, please hear our voices!" With this rallying cry in hand, the protesters didn't step down. Thus, Gorbachev's arrival could not be greeted with the traditional welcoming ceremony in Tiananmen Square.

On May 19th, Zhao Ziyang (who was, by this point, the primary voice in government who advocated for negotiating with the students, instead of military action) took matters into his own hands, by publicly begging the protesters to leave the square peacefully. Unfortunately, Zhao's efforts at compromise were frowned upon by the hardliners in government: May 19th marked the last time Zhao was ever seen in public. He was subsequently stripped of his title, denounced as a traitor, according to the New York Times, and confined to house arrest for his remaining years.

The military crackdown on Chinese citizens

On May 20th, 1989, as explained by Reuters, Li Peng declared martial law. Three days later, 100,000 protesters marched through Beijing, declaring that Li should be removed, and the Tiananmen Square crowds constructed a 33-foot tall tribute to the Statue of Liberty, called the Goddess of Democracy. Soon, these students were labeled "traitorous bandits," and as military involvement escalated, foreign presses tried to capture every moment, for the world to see.

In June, everything exploded. On June 3rd, thousands of Chinese soldiers — armed with guns and tear gas — charged toward Tiananmen Square, and were repelled by students. The following morning, tanks descended on the square, and opened fire on the thousands of unarmed Chinese citizens inside it. The scene was chaotic, as History describes, with countless young students desperately fleeing the gunfire while others tried to defend themselves by setting military vehicles ablaze. 10,000 protesters were arrested, and it is believed that thousands more were slaughtered, by the hand of their own government. This tragic, horrible event, the "June 4th incident," marked the end of the Tiananmen Square protests.

The world watched, in shock and horror. China's allies and enemies alike decried the military crackdown. China falsely claimed a death toll of 300, claiming that all but 23 of those casualties had been military officers. Deng Xiapoing praised the military, and condemned the murdered students. As for Li Peng, still considered by many as the "Butcher of Beijing," he retained his position until 1998.

How many people were actually killed at Tiananmen Square?

When the world expressed its horror at China's military crackdown upon their own citizenry, China tried to spin the events as a necessary action against "counter-revolutionaries," according to Reuters. Now, China's dual claim about there only being 300 deaths, and that most of the deceased were members of the military, is blatantly false on both counts. However, even now, the true death toll has never been fully confirmed.

For years, people on the scene speculated that a few thousand protesters had been murdered. Sadly, it seems that this estimation was too optimistic. As the BBC announced in 2017, newly-released British documents from the U.K. ambassador to China reported that the death toll in Tiananmen Square was monstrously higher — perhaps even as much as 10,000. The report also contained explanations of the sheer brutality with which the protesters were murdered, with descriptions of young students being bayoneted as they begged for their lives, while others linked arms only to mowed down, over and over again, until their bodies became "pie," that was later collected by a bulldozer.

Tiananmen Square's iconic Tank Man

Though the Chinese government did everything it could to silence the movement, the world remembers what happened. One image from the massacre, in particular, has remained an enduring symbol of freedom of resistance — and that image, of course, is Tank Man.

"Tank Man," as the New York Times explains, is the name given to the anonymous individual who, following the massacre, was filmed confronting an entire convoy of tanks, on his lonesome, with no weapons. As the video evidence shows, Tank Man stood before the tanks, blocking them. Even when they tried to move around him, or pushed forward and nearly ran him over, he refused to get out of their way. Even today, in the era of social media, nobody has ever pinpointed who, exactly, Tank Man really was ... or what happened to him. Thus, it's unclear whether his courageous act of defiance led to him being imprisoned, murdered, or saved. The Chinese military, government, and police are the only ones who might have answers, but they refuse to give them.

Decades later, Tank Man's prevalence as a symbol of rebellion has led the Chinese government to censor all images and/or references to him, and in 2019, they even convicted four men for selling bottles that referenced him, labeled with the phrase "Never forget, never give up." Most likely, Tank Man's true identity will never be revealed to the public, but his actions will always be remembered, and continue to inspire others.

Lies, propaganda, and coverups of the Tiananmen Square massacre

From the beginning, even before the military crackdown had occurred, the Chinese government tried to slander the student activists, according to the Guardian, by referring to the protests as "premeditated and organised conspiracy and turmoil." This sort of propaganda is, of course, the sort of thing that all authoritarian governments dish out when their own people are rebelling against them, as seen in countless other countries across the world.

However, these lies only hinted at the later, even more insidious silencing effort that was to come. In the decades since the Tiananmen Square massacre, the June 4th incident has been avoided, not spoken of, and erased from all Chinese schools, media programs, and textbooks. It's the single most taboo piece of the nation's history. Even now, in China, anyone who tries to publicly mark the event is cracked down upon. Relatives of the slaughtered protesters are not permitted to publicly mourn. When the massacre's 30th anniversary neared, Chinese writers, thinkers, and activists were placed under house arrest, beforehand, to prevent them speaking out, as foreign reporters were blocked (or removed) from Tiananmen Square. Essentially, China — in truly Orwellian fashion — has tried to wipe the event right out of their history book, according to the Washington Post, to the point of outright denying that they murdered thousands of their own citizens in cold blood.

A failed international response to the Tiananmen Square massacre

When the Tiananmen Square massacre occurred, the world had to respond. Sadly, many found these reactions to be deeply lacking.

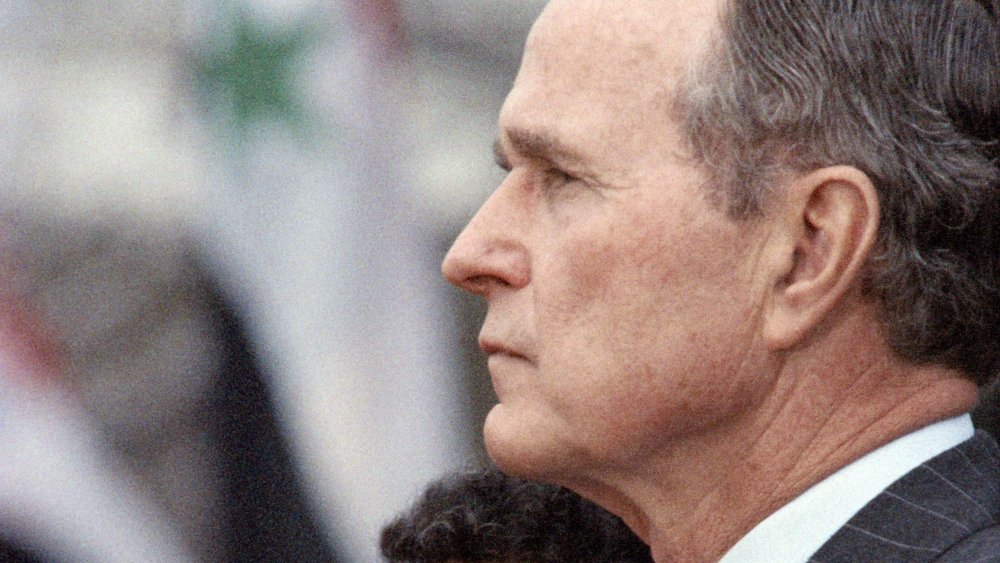

Certainly, as Foreign Policy writes, the international community quickly condemned the Chinese government's violence. After being pressed by congress, U.S. President George H.W. Bush even imposed an embargo on arms sales to China. Behind the scenes, though, the Bush administration also sent officials to meet with PRC leadership, mere months after the massacre, to reassure China that they wanted to maintain strong ties. Bush believed, as outlined by the Diplomat, that the future stability of the Asia-Pacific region depended on strong bilateral trade relations between the U.S. and China, and pushed aggressively to keep the two nations close, a decision he'd later be hammered on for during the 1992 election.

Now, how should the U.S. have reacted? Your argument there, as Psychology Today points out, probably depends on your foreign policy stance, since one doesn't have to look far to find examples of how badly foreign interventionism can go. Regardless, the U.S.'s failure to truly condemn China's actions did set a terrifying precedent, which continues to this day: While China has grown immensely in regard to power and influence, the human rights scandals have not ceased. As said by Bao Tong, an imprisoned ally of Zhao Ziyang, "There are miniature Tiananmens in China every day, in counties and villages where people try to show their discontent and the government sends 500 policemen to put them down."

Today, Tiananmen Square does not refer to the events

2019 marked the thirtieth anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre. The event was noted by many publications across the world, and marked by a candlelit vigil in Hong Kong. In mainland China itself, though, all mentions of the June 4th incident are blacklisted, propagandized, and/or punished.

If you visit Tiananmen Square today, according to CBS News, you will find no reference to the protesters who fought for a better, more democratic country, and were brutally slaughtered for their efforts. There are no markers. No plaques. The government's propaganda campaign is so widespread that when reporter Elizabeth Palmer visited the location and showed the Tank Man picture to young locals, they claimed to not recognize it. Minutes afterward, Palmer and her team were detained by police and held for six hour.

This erasure campaign has extended to the legacy of Hu Yaobang himself, according to the Atlantic. His name was, for 16 years, forbidden from all materials, and even when what would have been Hu's 90th birthday was commemorated in 2005, the man whose ideals inspired the June 4th movement was framed as someone whose reform initiatives stood perfectly alongside the current Chinese government's authoritarian views. This false portrait, sadly, couldn't be further from the truth. In 2018, according to the BBC, China's presidential term limits were eliminated, effectively allowing Xi Jinping to become president for life. And, in many regards, today's Chinese citizens are less free than they were before the 1989 massacre.