The Tragic Real-Life Story Of Frida Kahlo

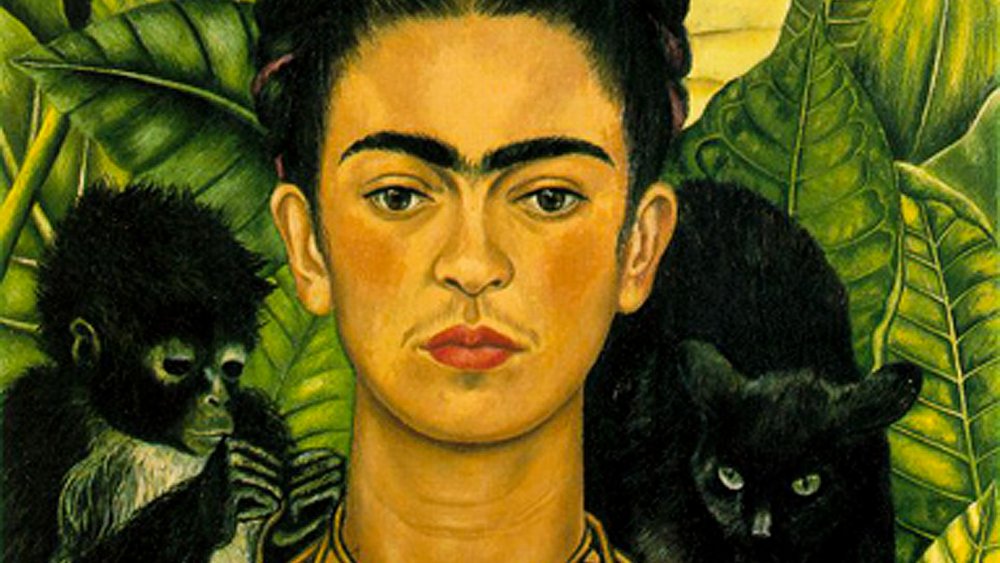

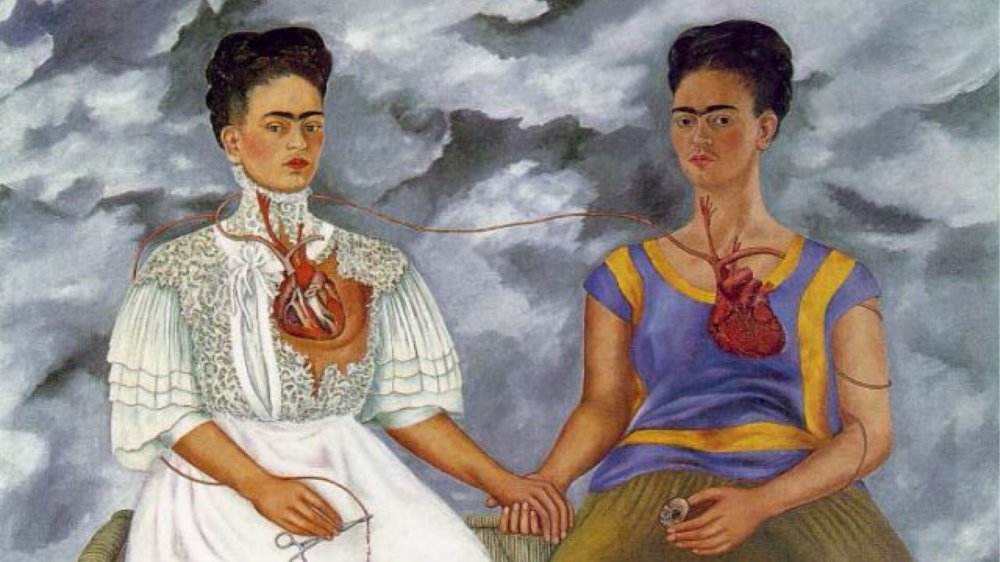

Frida Kahlo is one of the most admired artists of the 20th century. Her artistic talents are unmatched even today, and her works have sold for millions. But Kahlo's artwork has become indistinguishable from Kahlo the artist. According to the New York Times, in recent years Kahlo has "undergone transformation from a compelling cult figure to a universally recognized symbol of artistic triumph and feminist struggle" while at the same time becoming the "centerpiece of a kitsch marketing bonanza."

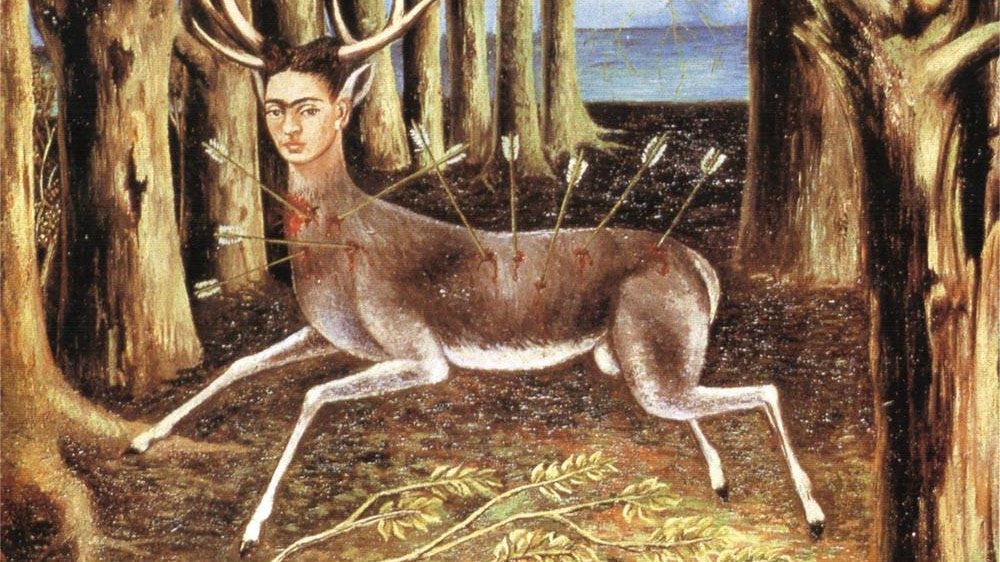

This so-called "Fridamania" shows no signs of stopping anytime soon, but the kitschy buttons, T-shirts, or tote bags emblazoned with Kahlo's iconic image do little to reflect to reality of Kahlo's troubled existence. Kahlo's great artistic genius came at a price. Her personal life was marred with tragedy, loss, illness, infidelity, and chronic pain that plagued her throughout her time on Earth. Kahlo never shied away from representing her struggles in her work. Perhaps it is this intermingling of her life and her paintings that has cemented her status in history as both a tortured artist and a global icon. This is the tragic real-life story of Frida Kahlo.

Frida Kahlo's childhood was not a happy one

Frida Kahlo was born into an unhappy household. Her father, Guillermo Kahlo, married her mother, Matilde Calderón y González, after the death of his first wife, but their marriage wasn't a loving one. According to Amy Fine Collins of Vanity Fair, Kahlo's mother had given birth to a son shortly before she became pregnant with Kahlo, but the child died in infancy. Matilde was still deep in mourning for her lost son when Kahlo was born in 1907. She was mentally unable to take care of her new daughter. Instead, Kahlo was passed off to be raised by wet nurses, not all of whom were up to the task. Matilde was forced to fire one of them for being drunk on the job.

Having been ignored since birth in favor of a lost son, it is not surprising that Kahlo felt pressure to fill that void. She took it on herself to fulfill the role of the "son" of the family. She was a textbook tomboy, pursuing sports like boxing and wrestling, and was her father's favorite child, presumably because she was the most like him.

While she was close to her father, he suffered from epilepsy and struggled with his health. Kahlo was not close to her mother, who she described as tense, cruel, and fanatically religious. Growing up neglected and sickly in a strict and largely loveless household, Kahlo described her own upbringing as a "sad" one.

Polio left Frida Kahlo permanently disfigured

When Kahlo was around 6-years-old, she contracted polio. The disease caused her right leg to thin and shorten. At first, Kahlo hid her deformity under bandages and thick socks, hoping it would go undetected by her parents. Her disease was not discovered for some time, and as a result, she never received proper treatment. Without the aid of a brace or orthopedic shoes, Kahlo developed a limp that caused lasting damage not only to her right leg, but to her pelvis and spinal cord. As she got older, her spine and pelvis grew in twisted and misshapen, causing permanently injuring her leg and back.

Per Vanity Fair, she was teased for her disfigurement by her peers, who called her "peg leg." But Kahlo found there was one upside to her disease. She got more attention at home, saying that "my papa and mama began to spoil me a lot and love me more."

Her father encouraged her to take up sports, like swimming, soccer, and wrestling. He believed activity would help heal her leg, but she never fully recovered from the effects of polio. Her leg and back remained permanently disfigured.

Frida Kahlo had a difficult time in school

Due to her health problems, Kahlo started school late, and was older than most of her classmates. According to Biography, she was not a terribly popular. As a child, she was bullied for her physical ailments.

Her sisters were enrolled in convents, but Kahlo's parents enrolled her in a German school instead. At the age of 13, the gym teacher at the school, a woman named Sara Zenil, singled Kahlo out. Zenil decided she was too fragile for sports, and pulled her out of class. Shortly after, Zenil initiated a sexual relationship with Kahlo, according to Vanity Fair. The sexual abuse continued until Kahlo's mother found compromising letters between Kahlo and Zenil. When her mother learned what was happening to her child, she pulled her out of the German school.

When she was 15, Kahlo was accepted to the elite National Preparatory School in Mexico City. She was one of only 35 girls who attended after it opened its doors to girls in 1922, according to The Art Story. While there, Kahlo finally seemed to find her footing. She did well academically. Planning to become a doctor, she studied anatomy, botany, and philosophy. She also made friends with a group of intellectual, left-leaning students who called themselves "Cachuchas." They exposed Kahlo to activist and social justice issues, and encouraged her interest in Mexican politics and identity.

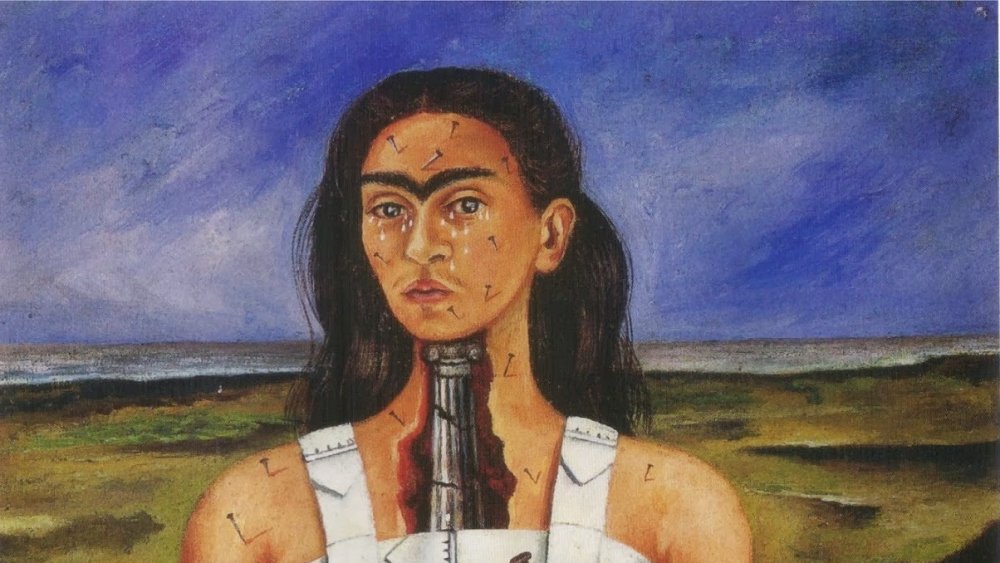

A bus accident nearly took Frida Kahlo's life

The 18-year-old Frida Kahlo was riding on a bus with her then-boyfriend, Alejandro Gómez Arias, when a trolley slammed into it. Arias survived the accident relatively unscathed, but Kahlo was impaled by a metal handrail, which tore through her pelvis. Kahlo was so badly injured that many onlookers did not believe she would survive the accident. Her pelvis was shattered, her spinal column and collarbone were fractured, and she suffered 11 fractures in her right leg, as well as a dislocated shoulder, according to Biography.

In a part of the story that seems more myth than fact, Kahlo's clothes were torn off in the accident. More strangely, another passenger on the bus had been carrying a packet of powdered gold, which broke open during the crash, covering Kahlo's naked, broken body with a shiny gold dust, according to National Geographic.

Kahlo was confined to bed for three months while she recovered. With nothing else to do, she began painting. Kahlo recounted the experience in 1938, writing: "I was bored as hell in bed . . . so I decided to do something. I stoled [sic] from my father some oil paints, and my mother ordered for me a special easel because I couldn't sit down... and I started to paint." She painted a self-portrait for Arias, but their love affair had soured when he refused to visit her while she was bedridden. While that relationship did not last, her relationship with painting was just beginning.

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera had a troubled relationship

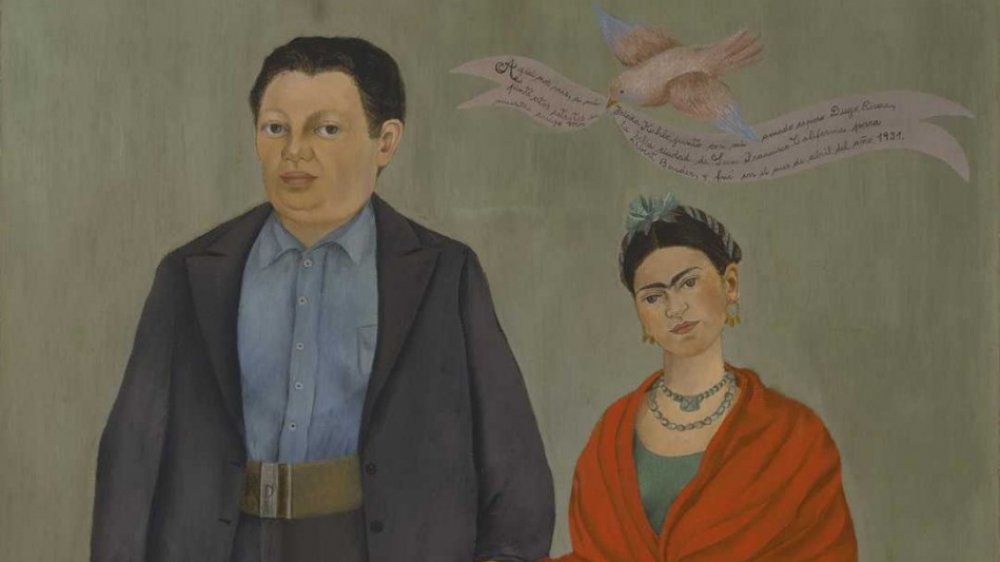

Kahlo first met the renowned mural artist Diego Rivera when she was 15 and he was 36. Unintimidated by his large size -– he tipped the scales at over 300 pounds and over six feet tall –- or his outsized artistic reputation, she went to see him after her accident and demanded he critique her paintings. According to Smithsonian Magazine, he was taken with her artwork, later writing that it was obvious to him "that this girl was an authentic artist."

He was also taken with the artist herself. They began a romantic relationship shortly after, to the displeasure of Kahlo's mother. Undoubtedly, they were an odd match. He was huge, and she was small and delicate. She was a teenager, while he was pushing middle age. But Kahlo was obsessed with him, and, over her mother's protestations, the couple was married in 1929, per The Art Story.

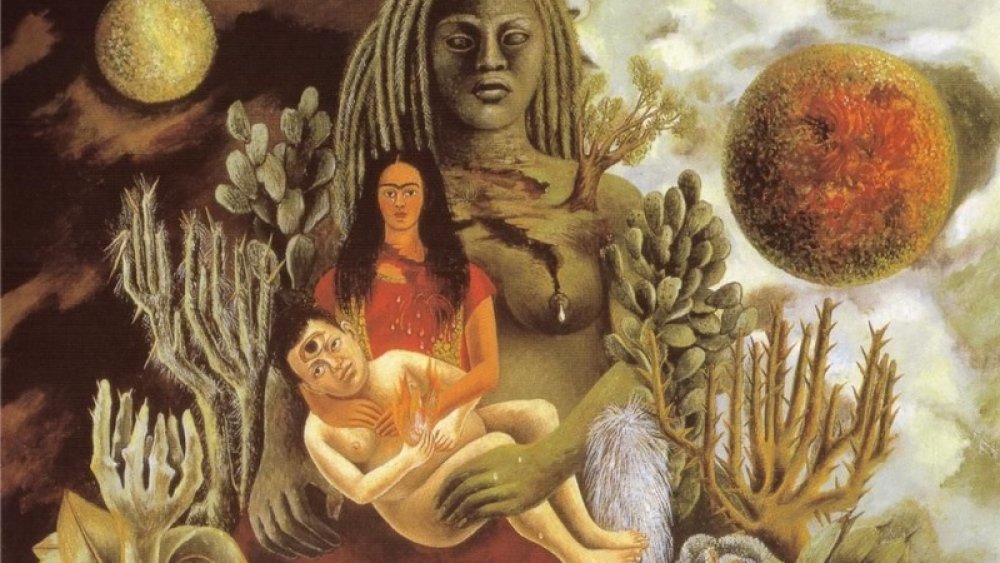

While Kahlo clearly loved Rivera, their marriage was far from happy. Both had affairs, and they fought bitterly over each other's infidelities. Rivera requested a divorce from Kahlo in 1939, but they couldn't stay apart for long. They remained in constant contact even after their separation, and less than a year later, they reconciled. Rivera and Kahlo remarried in December of 1940, and, though they both continued to have extramarital affairs, they remained married until Kahlo's death.

Frida Kahlo disliked 'Gringolandia'

In late 1930, the couple moved to America, after Rivera received a commission to paint murals for the Luncheon Club of the San Francisco Stock Exchange and the California School of Fine Arts. From San Francisco, Rivera's career took them to New York City for his MOMA retrospective, and then Detroit for another mural commission.

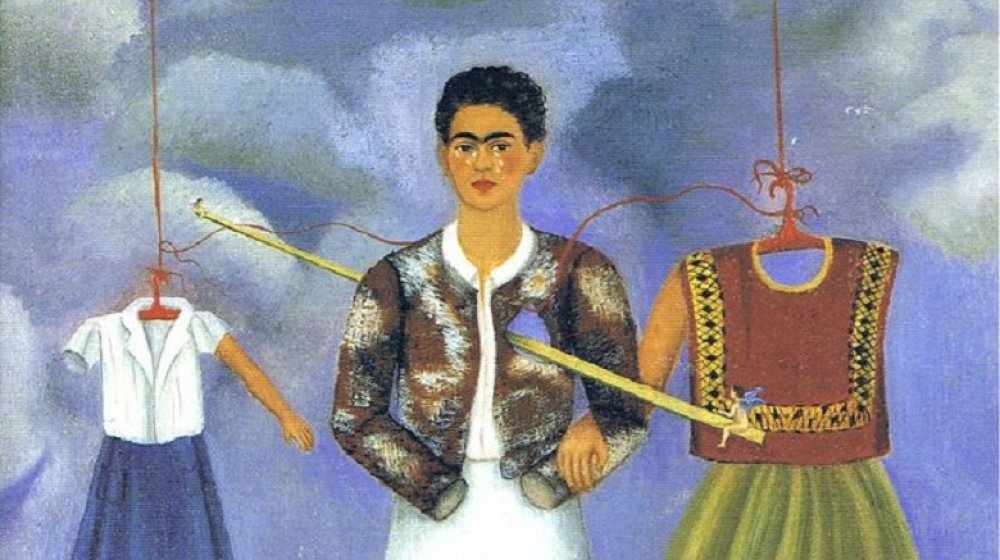

According to the New York Times, the couple was "lionized" in America. They rubbed shoulders with creative giants like photographer Imogen Cunningham and artist Georgia O'Keefe. Kahlo's creative work also flourished, and she created some of her most well-known works in these years, including Henry Ford Hospital (Flying Bed) and Self-Portrait on the Borderline Between Mexico and the United States (pictured). However, despite their popularity and creative success, Kahlo was homesick. She hated living in "Gringolandia." She disliked "the horrible poverty here and the millions of people who have no work, food or home" and the "filthy rich asses" for whom Rivera worked. Kahlo told friends back home: "I don't particularly like the gringo people...They are boring and they all have faces like unbaked rolls (especially the old women)," Andrea Kettenmann reported in her book Frida Kahlo, 1907-1954: Pain and Passion.

Kahlo pressured Rivera to return to Mexico, but he liked America and wanted to stay. He finally relented in 1933, but he remained resentful of Kahlo for forcing him to leave.

Frida Kahlo abused drugs and alcohol

Kahlo was a heavy drinker for most of her life. According to National Geographic, Kahlo supposedly drank a bottle of brandy daily. Kahlo was also fond of tequila, and she often surprised people who underestimated her tolerance due to her small size. Per Smithsonian Magazine, Rivera's second wife, Lupe Marín, was surprised and impressed by how "this so-called youngster" was able to drink tequila "like a real mariachi."

As she got older, both depression and chronic pain drove her to drink as a coping mechanism. Later in her life, Kahlo also abused prescription painkillers. Following an unsuccessful spinal surgery in 1946, Kahlo was prescribed morphine and Seconal, she abused those as well, even obtaining them illegally once her prescriptions ran out. Her excessive drinking and drug use began to take a toll on her already fragile health.

While living in San Francisco, Kahlo met a doctor named Leo Eloesser. He became a confidant and close friend for twenty years. Dr. Eloesser did his best to convince Kahlo to quit drinking to excess, recommending "bed rest, a more nutritious diet, cessation of alcohol consumption, and 'therapy'" as a better way to cope with her pain, according to the Oxford Academic Physical Therapy Journal. But Kahlo did not listen. She continued to drink heavily and use prescription drugs until the end of her life.

Kahlo and Rivera were notoriously unfaithful to each other

Both Kahlo and Rivera were extraordinarily unfaithful throughout their marriage. Rivera, a known womanizer, was already married to his second wife when he started seeing Kahlo, according to National Geographic. Rivera's many affairs upset Kahlo. Most devastatingly, Rivera had an affair with her younger sister Cristina in 1935. Upon finding out, Kahlo sunk into depression and cut off all her hair. Her friend Dr. Eloesser tried to comfort Kahlo, writing that "'Diego loves you very much, and you love him. It is also the case ... that besides you, he has two great loves: 1) painting 2) women in general. He has never been, nor ever will be, monogamous," via the Guardian.

Although Kahlo was deeply pained by Rivera's constant infidelity, she herself was not faithful. She took many lovers, both men and women. Sometimes she would attempt to get back at Rivera by seducing his female lovers, although Rivera seemed unbothered by her with affairs with other women. Kahlo had a 10-year affair with the photographer Nikolas Muray, per his official website. She also claimed to have seduced the great painter Georgia O'Keefe. She even had a love affair with Leon Trotsky, when the couple hosted him and his wife at their home after his exile in 1937.

While adultery caused Kahlo much emotional anguish, it also had unintended physical consequences. According to The Art Story, Kahlo suffered from syphilis, the result of either her or Rivera's many extramarital trysts.

Frida Kahlo was unable to have a child

Kahlo was desperate to give Rivera a baby. She conceived multiple times, but the metal rod that had punctured her womb in the bus accident had left her apparently unable to carry a child to term. According to Vanity Fair, she became pregnant once in 1929, just before her wedding, but was forced to have an abortion when it became clear her health issues would not allow her to endure childbirth. She conceived again after coming to America in 1932, but that pregnancy ended in a miscarriage.

Kahlo was distraught over her lost child, telling her friend Dr. Eloesser in a letter: "I had so looked forward to having a little Dieguito that I cried a lot, but it's over, there is nothing else that can be done except to bear it," per the Guardian. It is possible she had yet another pregnancy, which she chose to terminate because Rivera was not the father.

She fell into depression after every failed pregnancy. Despite her fragile health, Kahlo was still able to conceive, but she was never able to give birth to a child.

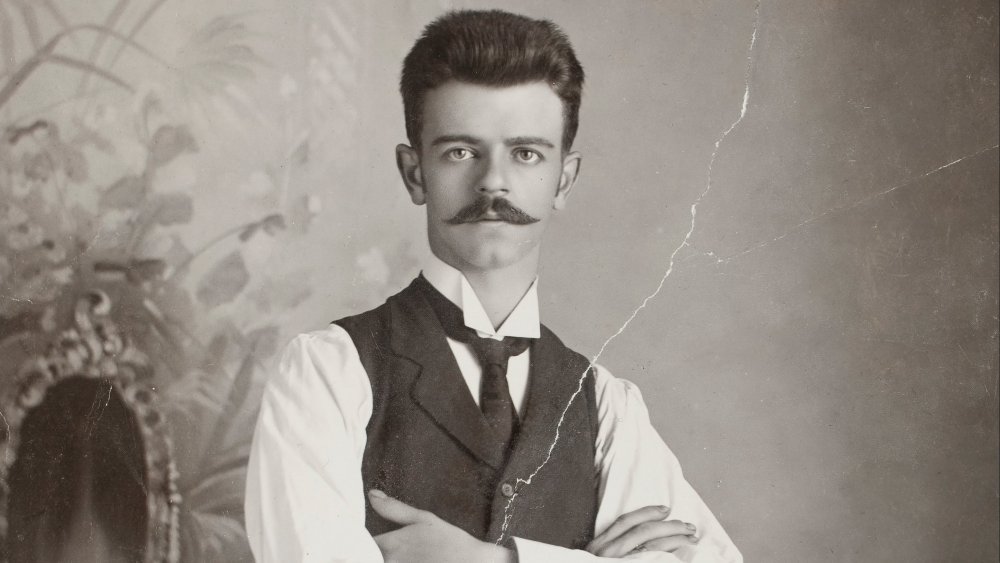

Frida Kahlo was exceptionally close to her father

The similarities between Frida and Guillermo Kahlo ran deep. Like her, Kahlo's father was both an artist and chronically ill. He suffered from epilepsy, and Kahlo would frequently nurse him through his epileptic fits, In turn, Guillermo cared for Kahlo during her period of invalidity following her near-fatal accident, according to DW.

Guillermo immigrated from Germany to Mexico in 1891, where he inherited a photography business from Kahlo's mother's family after their marriage. Kahlo frequently assisted him in the studio with his photography work, and it was there that she learned techniques of lighting, posing, and spacing that she would later incorporate into her own paintings. Guillermo always supported her artistic work, even arranging a drawing apprenticeship between her and one of his friends, an artist named Fernando Fernandez, according to The Art Story. Kahlo was her father's favorite child, and she was closer to her father than her other siblings. The pair shared a lifelong bond. He even went against his wife and supported her marriage to Rivera.

Guillermo died in April 1941, and she took the loss very hard. When her mother died, she did not even view the body, but she was deeply affected by her father's passing. Kahlo had been commissioned to paint a series of famous Mexican women, but she too overtaken with grief over her father's death (on top of her continuing physical problems) to complete the project.

Frida Kahlo tried to take her own life

Kahlo had been in chronic pain her whole life, and her husband had cheated on her for her whole life, but by the end of the 1940s, it all seemed to be too much. She was exhausted.

Her health had entered a rapid downward spiral, one that it was unlikely she would ever fully recover from. According to Biography, she spent nine months in the hospital in 1950, undergoing several unsuccessful surgeries on her spine, her foot, and her leg. She was increasingly immobile and mostly confined to a wheelchair after 1950. By the end of her life, Kahlo had undergone more than 30 surgeries.

While she was at her sickest, her husband had played the role of attentive spouse, but it didn't last. He soon returned to philandering. Kahlo couldn't take the constant heartbreak anymore. Depressed, ill, and exhausted, Kahlo tried to take her own life. In 1953, she was hospitalized again and it's believed that this time it was due to a suicide attempt.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

'I hope the leaving is joyful'

Kahlo's health had been steadily deteriorating for the last decade of her life. According to Biography, in August 1953, she had contracted gangrene on her right leg, and eventually had to undergo an operation to have it amputated below the knee. Also in 1953, Alvarez Bravo's Gallery of Contemporary Art hosted what would be Kahlo first and last solo art show in Mexico. She arrived on opening night in an ambulance. She was carried in on a stretcher and theatrically placed in the middle of a four-poster canopy bed for the rest of the show, per Smithsonian Magazine.

Kahlo was hospitalized with bronchial pneumonia near the end of that year. Her condition worsened over the next few months. On the morning of July 13th, 1954, Kahlo's nurse found her dead in her bed. She was only 47-years-old. Her official cause of death was listed as a pulmonary embolism, but many people were skeptical that she really died of natural causes, speculating that she may have succeeded in taking her own life after all.

Either intention or not, Kahlo knew that the end was near. According to Vanity Fair, the last words she ever wrote in her diary were: "I hope the leaving is joyful—and I hope never to return—FRIDA."