The Tragic Life Of Florence Nightingale

As a statistician, as a social reformer, and most importantly, as a nurse, few people have done more to improve public health worldwide than Florence Nightingale. Nightingale became a legend within her own lifetime. She launched an unprecedented heath and sanitary improvement campaign at the British military hospital in Scutari that saved countless of soldiers' lives during the Crimean War. Her work turned her into a media sensation, and images of the "Lady with the Lamp" dominated English papers during the conflict.

Her work did not stop with the war's end. Over the course of her life, Nightingale invented the modern nursing profession and changed the course of public health forever through her relentless drive and ambition. Her tireless work improved health care worldwide and saved countless lives. But it is a great irony that the woman who did so much to improve health care spent much of her own life sickly, reclusive, and adverse to the media attention that her successes brought. This is the tragic life of Florence Nightingale.

Florence Nightingale's family did not support her calling

Nightingale was born in 1820 in Florence, Italy, to a wealthy family. According to Biography, her mother, Frances, was from an elite family of merchants, and her father, William Edward Nightingale, was an affluent landowner. When Nightingale was a year old, they left her namesake city and returned with her to England. At first, they split their time between their two estates, Lea Hurst in Derbyshire and Embley Park in Hampshire, but the latter eventually became the primary family home, and Nightingale spent most of her childhood there.

Nightingale enjoyed many of the benefits of upper-class life. She was comfortable, well-traveled, and unlike most girls of the time, she received a rigorous education. Her father tutored her in math, science, philosophy, history, and the classics. But her family held very rigid, traditional beliefs about the role women were expected to play in society. They did not believe women of wealth should work outside the home. Instead, they should be focused on finding a suitable husband, marrying well, and maintain their class standing.

This became a point of contention when, at the age of 16, Nightingale received what she described as a call from God to become a nurse and minister to the sick. Her family, especially her mother, rejected this idea outright. Frances had married well, and she expected the same of her daughter. Nursing was not a suitable profession for a respectable woman, and Nightingale's family forbade her from pursuing her call.

Nursing was not a respected profession in Victorian England

Nursing as a formal profession did not exist until after Nightingale invented it. In the early 1800s, women who worked as nurses were lower-class and not well respected. They were perceived as lazy, disinterested, and generally inept women, who were too fond of the bottle and at times even dabbled in prostitution. This commonly held stereotype was exemplified by the fictional character, Sarah Gamp, a nurse in Charles Dickens' The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit, who was poor, uneducated, drunk, and occasionally cruel.

Wealthy, well-educated women, on the other hand, were not expected to work at all, let alone in such a lowly position. But Nightingale rejected her expected societal role. Instead, she devoted herself to performing charitable works and learning nursing as best as she could on her own. In 1850, Nightingale went to Germany to study nursing at Kaiserswerth, , according to Britannica, against her family's wishes. Nightingale trained for a little over three months, mastering the basics of patient care and hospital administration. In 1853, her father relented, and gave her a stipend that allowed her to move to London and accept the position of superintendent at the Institution for Sick Gentlewomen in Distressed Circumstances.

Florence Nightingale turned down two marriage proposals

Nightingale was strong-willed, stubborn, and even at times socially awkward, but according to nurse and writer Elisabeth Robinson Scovil, she still received her fair share of suitors. As a young woman, she rejected at least two proposals of marriage. Nightingale's cousin, Henry Nicholson, proposed to her in 1844, but Nightingale turned him down. The second proposal, however, caused her much more grief. Nightingale met the poet Richard Monckton Milnes in 1842, and he was her suitor for seven years. He proposed to her in 1847, and she took her time thinking it over. Nightingale was very fond of Milnes, and the decision was not an easy one. According to biographer Sir Edward Cook, she felt a "passional" attraction to Milnes, and she believed she "could be satisfied spending a life with him, combining our different powers in some great object."

Finally, in 1849, he pressed her for a final answer, and she turned him down one last time. She believed marriage would interfere with her calling to help people, ultimately deciding she could not be satisfied "spending a life with him in making society and arranging domestic things. . . . To be nailed to a continuation and exaggeration of my present life, without hope of another, would be intolerable to me. Voluntarily to put it out of my power ever to be able to seize the chance of forming for myself a true and rich life would seem to me like suicide."

Florence Nightingale struggled with depression throughout her life

Throughout her 20s, Nightingale suffered from frequent bouts of depression. She believed that nursing was a Divine calling, and her family's constant refusal to support her vocation exacerbated her dark moods. In 1845, Nightingale's parents refused to allow her to go to Salisbury Infirmary to pursue nursing. She became increasingly frustrated by the confines of her life.

Her relationship with Milnes was another source of distress. She struggled for years with her decision to marry or not. She struggled under the pressure of her relationship with Milnes and her family's constant disapproval. According to the New World Encyclopedia, she suffered a mental breakdown in 1847. She went to Rome to recover, where she met Sidney Herbert, a politician and secretary of war. This meeting changed the course of her life. Herbert became a lifelong friend, confidant, and political ally, and she became one of his most trusted advisers.

But it did not put an end to her periods of unhappiness. Nightingale wrote in 1850: "In my thirty-first year, I can see nothing desirable but death...my present life is suicide." She remained uncertain if she had made the right decision rejecting Milnes's marriage proposal, writing: "I know that if I were to see him again, the very thought of doing so quite overcomes me. I know that, since I refused him, not one day has passed without my thinking of him, that life is desolate to me to the last degree without his sympathy."

Florence Nightingale fought her own battles in the Crimean War

In 1854, Britain went to war with Russia on the Crimean Peninsula. The New York Times reported the British military lacked the necessary infrastructure to care for their wounded soldiers. Many men languished in poorly-kept hospitals, dying not only of their injuries but of preventable illnesses such as typhoid, dysentery, and cholera.

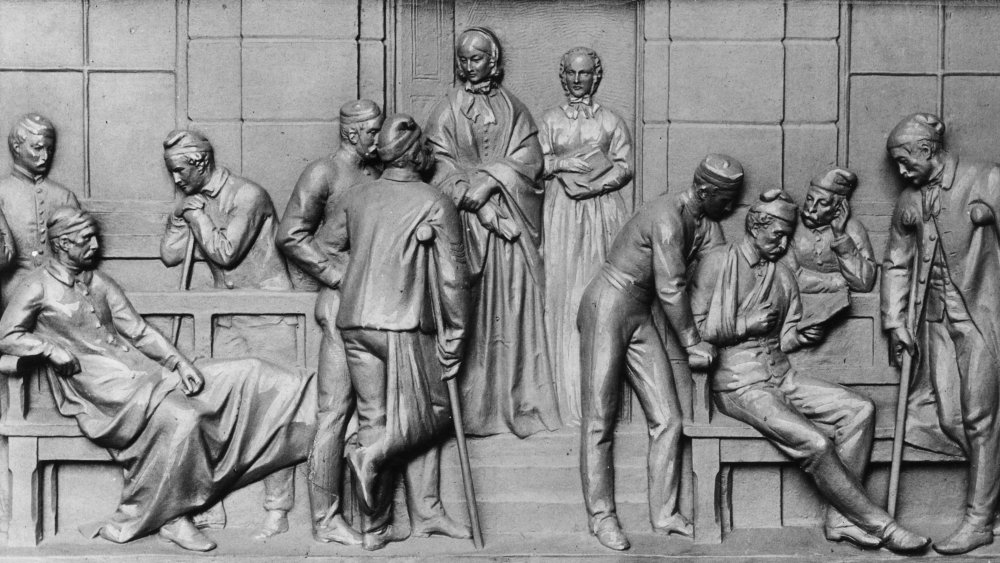

According to the BBC, when news of the treatment of wounded soldiers reached England, public outrage forced Sectary of War Sidney Herbert to seek out Nightingale's help. In October 1854, Nightingale led a group of 38 volunteer nurses to Scutari to improve the dismal conditions at Barrack Hospital. She encountered the terrible unsanitary conditions, filth, and overcrowding. She also dealt with inadequate supplies, overworked and uncooperative staff, and a death rate of over 40 percent. In the winter of 1855, 4,077 British soldiers died at Scutari.

Immediately, Nightingale pushed for a sanitary commission to flush the latrines, clean the water supply, and improve air flow in the wards. She was met with resistance, butting heads with commanding officers and uncooperative male doctors, but she eventually succeeded. Smithsonian magazine reported that, with improved ventilation and sanitary procedures, the death rates dropped to just 2.2 percent. In between implementing structural changes, managing her stuff of volunteers, and lobbying the government for funds, Nightingale still found time to administer hands-on care to her patients. She wandered the wards at night, a lamp in hand, earning herself the nickname "The Lady with the Lamp."

Florence Nightingale contracted an illness in the war that would affect her for the rest of her life

In the spring of 1855, Nightingale traveled to the Crimean Peninsula. Her goal was to assist with medical care at Balaklava military hospital. She made several trips to the Peninsula, but on one of her excursions there she contracted Crimean Fever, otherwise known as brucellosis. It is a highly contagious bacterial infection that Nightingale most likely contracted by coming into contact with contaminated animal products, like milk. Weakened by her illness and slow to recover, she was forced to leave the Crimean Peninsula.

However, rather than return home to England, Nightingale went back to Scutari, where she remained until the end of the war. According to Britannica, the Treaty of Paris signed in Arch of 1856, effectively ending the war. The military hospitals in Turkey closed that spring, and Nightingale finally returned home to England in August of 1856. Nightingale never fully recovered from brucellosis, and the ill effects of the disease lingered for the rest of her life.

Florence Nightingale became a heroine in England

News of Nightingale's work in Scutari had reached the press, and she became a media sensation in England. Her dramatic reduction of mortality rates and improvement of hospital conditions earned her recognition and praise. The Times described her as "a 'ministering angel' without any exaggeration in these hospitals, and as her slender form glides quietly along each corridor, every poor fellow's face softens with gratitude at the sight of her. When all the medical officers have retired for the night... she may be observed alone, with a little lamp in her hand, making her solitary rounds." The poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, embellished the image in his poem Santa Filomena:

Lo! in that house of misery

A lady with a lamp I see

Pass through the glimmering gloom,

And flit from room to room.

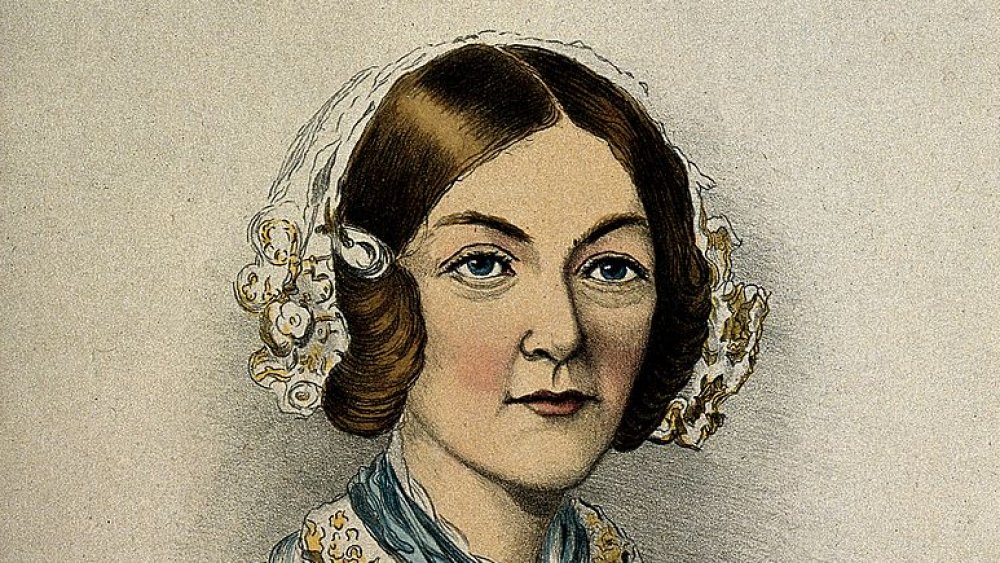

The image of the lady with the lamp stuck. A portrait in the Illustrated London News (pictured), published in February 1855, depicted Nightingale tending to rows of sick patients, holding a lamp to light her way. Nightingale's iconic image was reproduced on keepsakes and sold. The public loved her, even sending her fan mail.

When she finally returned to Derbyshire in 1856, she was lauded as a heroine of the Crimean War, but all the attention made her uncomfortable. Nightingale, exhausted and battling the effects of Crimean Fever, shied away from the spotlight. She preferred to stay in her home, doing most of her important work away from the public eye.

Nightingale had to rely on male allies for help

Nightingale's intelligence and ambition was unmatched. According to the New York Review of Books, her work revolutionized health care institutions. Her most notable works, Notes on Hospitals and Notes on Nursing: What It Is and What It Is Not, detailed the proper ways to run a sanitary hospital and administer care to the sick. She turned nursing into a respectable profession held to strict standards of care.

She was also a brilliant statistician, using graphs and pie charts to display her reports. She used her findings to lobby the government to improve public health, particularly in rural India. She advocated for improved sanitation, helped establish an improved drainage system that reduced the spread of fatal diseases, and supported efforts to relieve famine and poverty.

Yet, despite all she accomplished, she still had to face the limitations of being a woman. Although her social standing did command some respect, she still lacked any real authority to implement her ideas. She was reliant on male allies, notably politically influential figures like Sidney Herbert and John Sutherland, to bring her ideas into reality, while she worked in the background. But the limitations she faced only drove her to work harder. Nightingale held herself and other women to high standards, and often criticized her sex for falling short, admonishing those who "have only tried to be 'Men' & they have only succeeded in being third-rate men." Her harsh critiques and overall complicated relationship with feminism has led to some criticism, as Vice reported.

Florence Nightingale struggled with chronic illness throughout her life

In spite of all she did to improve the health of others, Nightingale spent most of her own life in a bad way. She was intermittently bedridden after 1857. Her biographers believe she suffered from the lingering effects of the Crimean Fever that she contracted during the war. There was no cure, and Nightingale suffered from symptoms of the disease for the rest of her life. The disease contributed to a host of other medical complications, including irritability and insomnia, nausea, weakness, and fatigue.

Her brucellosis would flare up on and off throughout her life. Some attacks were worse than others. Journalist DAB Young reported that in December 1861, Nightingale suffered from a particularly severe attack that left her unable to walk. She was unable to leave her home for six years. The attack also caused chest pains and headaches, and the pain combined with her solitary confinement contributed to bouts of depression, loneliness, and feelings of worthlessness. Nightingale used opium to cope with the worst of the symptoms, but there was only so much that could be done for the women who had done so much to help others. Although the worst of her symptoms seemed to have improved after 1880, she never fully recovered and remained infirm for most of her adult life.

Nightingale might have also suffered from spondylitis

In 2008, Nightingale biographer Mark Bostridge put forth the theory that Nightingale also suffered from spondylitis, a chronic inflammatory spinal disease for which there was no cure. The disease caused back and joint pain, swelling, and stiffness. Over time, the bones of the spine can fuse together and new ones can form, causing immobility. The onset of the disease most likely started when Nightingale was in her 40s, and continued to worsen with age. With little effective treatment available for the condition, the pain often forced Nightingale to remain in bed for weeks at a time. Although there are rumors that Nightingale took bromide to lessen her libido, Bostridge's research shows that she actually took the bromide to ease her spondylitis symptoms and help lessen the pain.

According to Bostridge, spondylitis "is what kept her bedridden during the 1860s. Somebody once said that posterity has done Florence Nightingale a great disservice by saying she wasn't suffering from an organic disease. She was."

Florence Nightingale struggled with her mental health

While it is known Nightingale suffered from multiple physical illnesses in her life, some modern psychiatrists speculate it is possible she had serious mental ailments as well.

According to Dr. Katherine Wisner, a professor of psychiatry and obstetrics/gynecology at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, it is possible Nightingale actually suffered from untreated bipolar disorder throughout her life. She suffered from well-documented bouts of depressive episodes in her teens and twenties, and the Divine calling she claimed to have received from God might also be explained if Nightingale heard voices in her youth. Both of these symptoms can be indicators of bipolar disorder.

In her adult life, Nightingale had documented mood swings that her physical ailments alone might not fully account for. Nightingale was intensely ambitious, and she was extremely driven and productive, writing prolifically and working tirelessly from her home. But her life was punctuation by bouts of seclusion, fatigue, listlessness, and depression. Dr. Wisner suggests that "illness alone does not account for her severe mood swings, or the fact that she could be so incredibly productive and so sick at the same time."

Florence Nightingale's death made national headlines

Nightingale never married and had no children. Her work was her legacy. At the end of her life, she became even more reclusive, although she did receive two great honors for her achievements shortly before her death. According to the National Army Museum, Nightingale received the title of Lady of Grace of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem in 1904, and she became the first woman to be granted the Order of Merit in 1907.

Nightingale's obituary in The Guardian reported her death at the age of 90 from heart failure in 1910. Because of her many accomplishments, Nightingale was eligible for a state funeral and burial at Westminster Abbey, but her will specified that her service be a reserved affair. In keeping with her final wishes, her family declined the offer of the state funeral. Instead, Nightingale's memorial was held at St. Paul's Cathedral in London. She was laid to rest on her family's plot at St. Margaret's Church in East Wellow, Hampshire, not far from her father's estate at Embley Park.