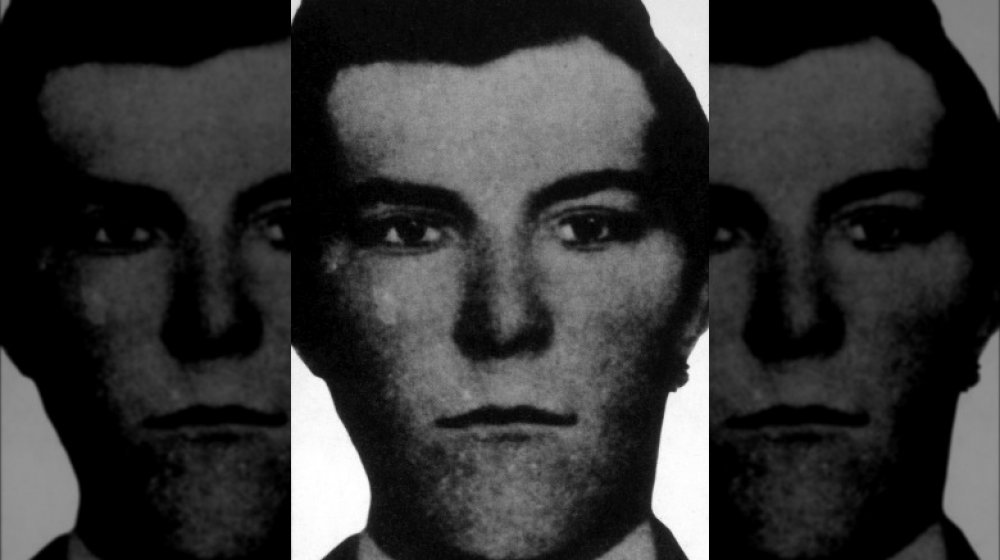

The Crazy Real-Life Story Of John Wesley Hardin

When you think of the phrase "Wild West,” certain things are likely to come to mind. You've got saloons, geographically misplaced cacti, no-nonsense sheriffs, and, of course, outlaws — hard, icy-eyed men who shoot first and ask questions never. Loyal only to themselves and always on the lookout for the next big score, these criminals leave trails of corpses in their wake. And as far as outlaws go, few check all the boxes better than John Wesley Hardin.

A perennial fugitive, Hardin shot down rivals, lawmen, and soldiers, and he did much of it before he was old enough to grow the requisite handlebar mustache. Many of the details of Hardin's life come from his autobiography, which he wrote while in prison for murdering a lawman. As he had a reputation for making exaggerated claims, Hardin's own accounts of his exploits should be taken with a grain of salt, but no one doubts that he was a vicious gunslinger to be crossed at one's own peril. His real-life story is a crazy one indeed.

John Wesley Hardin first saw murder at eight years old

John Wesley Hardin Hardin was born in Bonham, Texas, on May 26, 1853, the son of a traveling Methodist preacher who became a lawyer in 1861. With the outbreak of the Civil War that year, Hardin was exposed to a Texas-sized helping of violent anti-Yankee rhetoric. Years later, he recalled frequently seeing effigies of Abraham Lincoln shot and burned.

Hardin would witness murder for the first time in 1861, as well. In his autobiography, he recounts the story of an old pauper by the name of John Ruff, who owed money to a much richer man, Turner Evans. One night, Evans had been drinking, and he began to roam the town of Sumpter, Texas, (Hardin's home at the time) with an entourage, looking for Ruff. Evans proclaimed to anyone within earshot that he'd cane Ruff once he found him, which he finally did in a small grocery store.

Before eight-year-old Hardin's eyes, Evans confronted Ruff, insulting and deriding the old man. Ruff told Evans to leave, to which Evans replied that he would only after he'd caned Ruff, a statement he punctuated with a blow to Ruff's head by said cane. But Ruff had had it. He pulled a Bowie knife and lunged at Evans. Despite more blows from the latter's cane, as well as strikes from chairs wielded by his friends, an enraged Ruff opened Evans' throat, severing his jugular. Ruff was arrested, Evans soon died, and Hardin had seen his first killing.

He committed his first murder at age 15

Hardin was never one to shy away from a fight. He claims to have hatched a plan at nine years old to run away with one of his cousins to fight against the North in the Civil War, an idea his father shot down by giving him "a sound thrashing." He nearly became a murderer at 14 during an altercation with a schoolmate whom Hardin described as a bully. The boy in question, Charles Sloter, had written a disparaging statement about a female classmate on the blackboard and blamed Hardin. Upon Hardin's denial, Sloter allegedly punched him and pulled a knife. Hardin drew a blade of his own and stabbed Sloter in the chest and back, almost killing him.

Things didn't turn out so well for Hardin's next adversary. As told by historian Leon Metz, one day in November 1868, Hardin, 15, had gone to visit his uncle. There, he and a cousin pitted themselves against a former slave named "Mage" Holshousen in a wrestling match (likely because neither teen could've pinned the man alone). During the match, Holshousen was thrown to the ground, resulting in a cut to his face. Angered, Holshousen threatened Hardin, whose uncle ordered Holshousen off the property. The next day, Hardin was riding home when he came across Holshousen, who — according to Hardin — intercepted the boy and grabbed his horse's bridle, stopping the animal. Hardin pulled a Colt .44 and shot Holshousen dead.

How John Wesley Hardin became a fugitive

Neither Hardin nor his father believed he'd get a fair trial for murdering a black man. The Civil War was over, and Texas was ruled by the North. Historian Leon Metz, however, notes that had Hardin gone to trial, he would likely have been acquitted by an all-white jury. Nevertheless, Hardin fled to Logallis Prairie, where his older brother Joseph worked as a teacher. Fearing the prying eyes of the military, he stayed not with Joseph but with an old man named Morgan, who lived nearby. Hardin spent the next six weeks hunting in the wilderness.

In December 1868, Joseph warned his younger brother that three soldiers were in the area, and they were asking about Hardin. The teenage fugitive took his Colt, as well as a double-barreled shotgun, and lay in wait at Hickory Creek Crossing. When the soldiers came by, Hardin ambushed them, killing two with a blast from each barrel of the shotgun. The third fled, and Hardin pursued, demanding that the soldier surrender in the name of the now-defunct Confederacy. Instead, the soldier shot back at Hardin, hitting the boy in the arm. So Hardin killed the man. A few sympathetic local farmers buried the three soldiers downstream, and Hardin, fully committed to the life of an outlaw, fled once more.

He was wrongfully arrested once

On January 9, 1871, Hardin rode into Longview, Texas. There, the 17-year-old was arrested for stealing a horse and for four murders. As detailed by Leon Metz, he was soon released but was quickly rearrested, this time to be sent to Waco to stand trial for horse theft and yet another murder. Although Hardin was never one to shy away from taking credit for a death, he denied responsibility for these crimes in his autobiography.

Hardin found himself in jail awaiting transfer. Hoping to escape, Hardin bought a smuggled — and loaded — Colt .45 from a cellmate. He even hatched a doomed escape plan, but unable to convince his three cellmates to go along with it, Hardin had no choice but to wait to be taken to Waco.

A few days later, Lieutenant E.T. Stakes, who'd arrested Hardin, and Private Jim Smalley came to ferry the teen to Waco. Hardin was placed on a pony without a saddle, and the three began a 175-mile trek through the winter cold. As evening fell on January 22, the group made camp near Waco. Stakes left for supplies, leaving Smalley to guard their charge. According to Hardin, Smalley liked to threaten him at such times. In this case, Hardin leaned against the pony and pretended to cry while reaching for his gun. Smalley reached for his own weapon when he saw Hardin's Colt, but it was too late. Hardin shot Smalley dead and escaped on the private's horse.

John Wesley Hardin's face-off with Wild Bill Hickok

By June 1871, Hardin had found himself in Abilene, Kansas, the marshal of which was one "Wild Bill" Hickok (pictured). In his autobiography, Hardin admitted to a desire to test the lawman. At the time, Abilene had a ban on wearing pistols, so continuing to wear his was all Hardin had to do. Indeed, as Hardin and others were having a raucous good time in a saloon, Hickok showed up due to complaints about the noise. Seeing Hardin's six-shooters, Hickok told him he'd have to relinquish the weapons until he was ready to leave Abilene. Hardin responded that he was willing to leave town, but he wouldn't give up his weapons. The two gunslingers headed outside.

After they'd exited, Hickok pulled his own gun on Hardin and demanded the latter's revolvers. As Hardin tells it, he obliged, offering his guns handle-first. As Hickok reached out to take them, Hardin whirled his pistols around, leaving Wild Bill staring down the barrels of both. Hickok praised Hardin's speed and offered a truce by way of a drink in the saloon. Hardin, though wary, accepted the offer, and according to him, the two spoke at length inside and became friends.

He may have killed a man for snoring

An oft-repeated statement about Hardin is that he was so mean that he once killed a man for snoring. As True West Magazine notes, the truth of the story is murky. In August 1871, Hardin was staying at the American House in Abilene, as was his unfortunate victim, Charles Couger. It's known that Hardin (who'd been living in Abilene under the alias "Wesley Clements") shot Couger through the wall of his room, but no newspaper accounts of the murder state that Couger was snoring. One, however, did say he was reading a newspaper. Nevertheless, the story that Hardin killed Couger for snoring has been told since at least 1877.

Leon Metz, something of an authority on Hardin, has offered his own speculation as to what happened that night. According to him, Couger was asleep when Hardin and another man, Gip Clements, stumbled in drunk. Couger's snoring kept the two awake, so they shouted at him to pipe down. Couger perhaps sat up and read a bit as a result, but he drifted off again, snoring louder than ever. This time, Hardin and Clements fired several shots through the thin wall to show Couger that they meant business. Instead, they killed him. Whatever Couger was doing when he was shot, Hardin knew Wild Bill Hickok wouldn't let him get away with this, so it was time to flee once again.

He was forced to surrender after getting shot twice

Hardin's luck turned south in August 1872 in Trinity City, Texas. According to Legends of America, he'd beaten a man named Phil Sublett at poker, and Sublett wasn't happy. As Hardin stepped out onto the street, Sublett fired one barrel of his shotgun at Hardin, but he missed. Hardin later recounted that he didn't want to get in any more trouble, so he deliberately missed when he returned fire. Sublett fired his other barrel, and two pieces of buckshot hit Hardin in the kidney. Sublett ran, and Hardin, rapidly losing blood, couldn't catch him. One of Hardin's cousins showed up, and the gunfighter gave him gold and silver to be carried to his wife, Jane, who was in the town of Gonzales. (Yes, Hardin had actually gotten married.)

A doctor removed the buckshot, and Hardin decided to lay low for a little while. But then a few weeks later, Hardin killed one of two policemen who came looking for him, receiving a new wound in his thigh for his trouble. Now weaker than ever, he arranged to surrender to the sheriff, lest he be killed by an angry mob. Sheriff Dick Reagan came, and as Hardin was surrendering his pistols, a jumpy member of Reagan's crew shot Hardin in the knee. After a few more weeks of recuperation, Hardin was moved, first to Austin and then to Gonzales, where murder charges awaited. But on October 10, 1872, he cut through his jail's bars with a saw and was on the run yet again.

John Wesley Hardin killed the wrong man

Of all the people Hardin killed, the most consequential murder in his life would be that of Deputy Sheriff Charles Webb. On May 26, 1874, Hardin was celebrating in a saloon in Comanche, Texas, where he lived with his family. On top of it being his 21st birthday, Hardin had won big betting on horse races that day. His party, though, was about to be crashed.

When Webb, who'd come from Brown County, showed up, Hardin was naturally suspicious of the lawman, but Webb claimed he wasn't there for him. According to True West Magazine, however, he had indeed come to collect a bounty on Hardin, dead or alive. By his own recollection of that day, Hardin saw Webb pull a pistol, so he jumped sideways and drew his own gun. Webb's shot tore a nasty gash in Hardin's left side, and his return shot struck Webb in the left cheek. Webb went down as Hardin's group peppered him with bullets.

Hardin and a friend, Jim Taylor, fled, pursued first by an angry mob and eventually by Texas Rangers. Hardin's older brother Joseph and two of his cousins, Bud and Tom Dixon, were later lynched by the townsfolk. Hardin swore revenge, but there was little he could do.

A silly blunder led to his final capture

In January 1875, the state of Texas put a $4,000 bounty on Hardin. Per the Texas State University's John Wesley Hardin Collection, he, his wife, and his daughter ultimately fled to Pollard, Alabama, near the Florida border, with Hardin taking the name "J.H. Swain." Hardin lived a relatively quiet life here, fathering two more children over the next three years. Through all of this, the Texas Rangers still hunted him. As detailed by the Texas Bar Journal, the Rangers knew of Hardin's alias, and when they got their hands on a letter addressed to "Swain" in Pollard, they headed east.

In August, they found Hardin sitting in a train in Pensacola, Florida, as people boarded. Ranger John Armstrong, as well as local law enforcement, moved in, stationing themselves on each side of Hardin's train car. The men burst in, and a surprised Hardin reached for his pistol. This time, however, the gun was caught in the fugitive's fancy suspenders. Armstrong reached Hardin and clubbed him, and the outlaw was finally caught. Though the Rangers had no authority in Pensacola, History Collection notes that the local police were more than happy to help them get Hardin back to Texas post-haste. And when he returned to the Lone Star State, an Austin jury sentenced Hardin to 25 years in prison for the murder of Charles Webb.

Escape attempt after escape attempt

Hardin began his sentence in Huntsville, Texas, in October 1878. Barely had he stepped through the door before his mind turned to escape. And his first escape attempt was pretty crazy. He hatched a plan to tunnel to the armory, grab the guns, and take the prison. He recruited several able-bodied confidants, and clandestine work began in early November. The tunnel was nearly complete by the 20th, at which point several convicts snitched on Hardin, who received 15 days in solitary.

Next, Hardin came up with the idea of fabricating his own keys to the cells in his row, but once again, another prisoner ratted him out. Hardin was stripped naked and flogged for his efforts. By June 1879, Hardin wasn't nearly as keen on trusting other inmates, so he tried bribing a guard, this time letting only a single other prisoner in on his plan. He was flogged yet again, though "not so cruelly as before," according to him. Hardin claimed to have been flogged another time afterward for nothing at all.

Hardin kept hatching new escape plans, but in the fall of 1883, his old kidney wound developed an abscess, and he was left bedridden for eight months, effectively shutting down any hope of getting out on his own terms. In 1885, Hardin began to focus his efforts on studying law, hoping to become a lawyer as his father had been. But in 1892, his wife, Jane, who'd stuck by him through his life on the lam, died. In other words, things were looking pretty rough for John Wesley Hardin.

John Wesley Hardin's inauspicious death

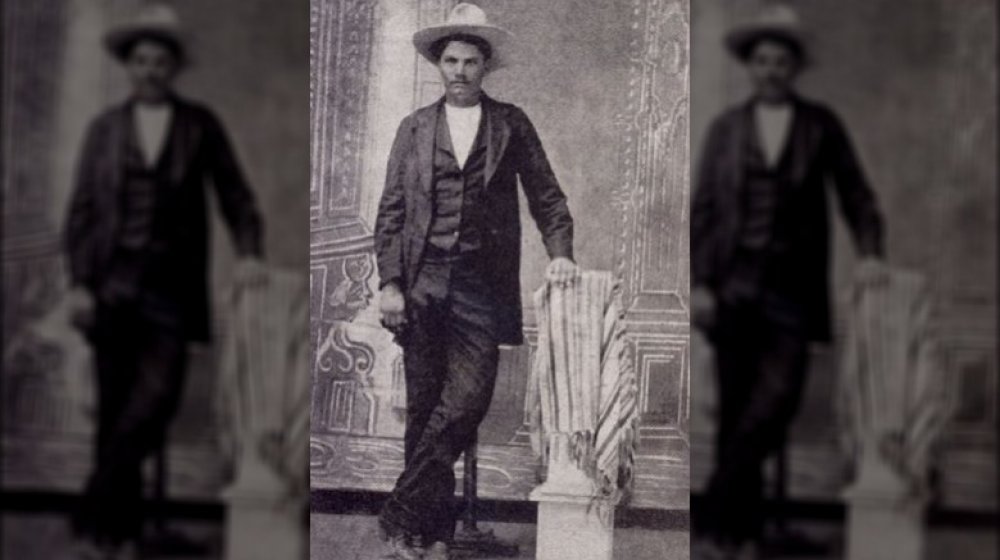

In February 1894, Hardin was released from prison for, believe it or not, good behavior. He received a pardon in March and was officially a free man. Per the University of Texas, Hardin, now 40 years old, returned to Gonzales to be with his family. Here, the outlaw became a lawyer, passing the bar and starting his own law practice. In December, he moved to Junction, where his brother lived, and continued to practice law. While there, he married a 15-year-old girl named Callie Lewis, but according to True West Magazine, she left him after five days.

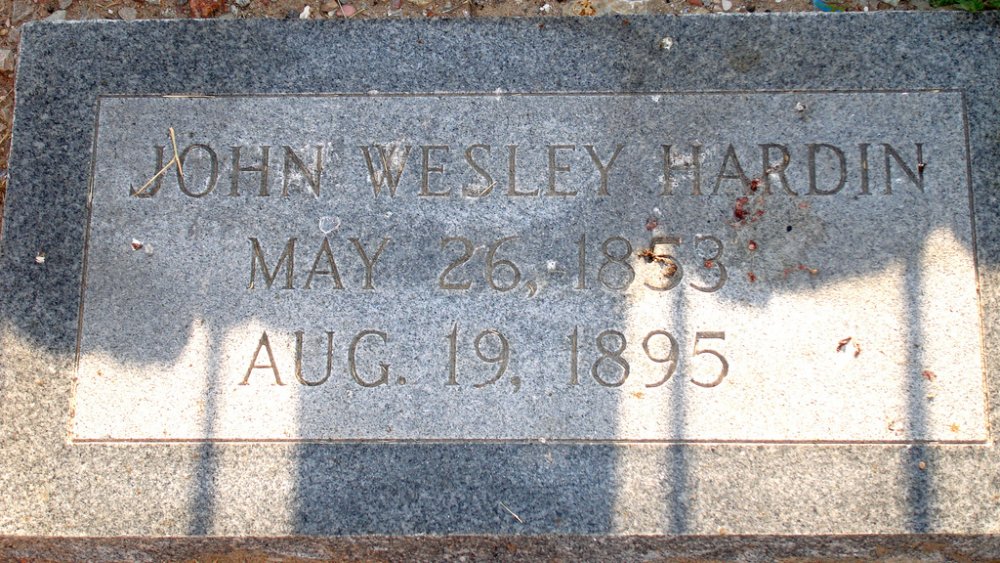

Hardin ended up in El Paso in 1895, where, as noted by History, the carrying of guns had recently been outlawed in an attempt to reduce violence. In August, Hardin's girlfriend was arrested for possession of a gun by a police officer named John Selman. Hardin, still temperamental, found Selman and threatened him for what he'd done, an altercation witnessed by several bystanders. It was to be Hardin's last. On August 19, as Hardin was sitting in the Acme Saloon, Selman, off-duty at the time, walked up behind Hardin and shot him in the head. The slain gunslinger was buried in El Paso's Concordia Cemetery.

The fight over John Wesley Hardin's remains

For most people, a gunshot to the back of the head would be a solid punctuation mark to the end of their story. Not so for Hardin, whose remains became the focus of a fight between residents of El Paso and Nixon, Texas, in the mid-1990s. Early one morning in August 1995, as reported by the Chicago Tribune, a small group consisting of Hardin's descendants and Nixon residents slipped into Concordia Cemetery with an order to disinter Hardin and take him back to Nixon to be buried next to his first wife. They were met by historian and El Paso resident Leon Metz, other city residents, and police officers. According to the Associated Press, they had a restraining order barring the Nixon group from taking Hardin's body.

Each side had words for the other. Metz accused Nixon, a small town east of San Antonio, of simply seeking Hardin's remains for use as a tourist attraction and pointed out that Hardin only lived there for a very brief time. The Nixon group sought to paint Hardin as a family man who'd put down roots in their town. In February 1996, a judge ruled that Hardin's grave wouldn't be moved, and despite appeals, he remains buried in Concordia.