The Messed Up History Of Australian Penal Colonies

Australia has a strange and fascinating history, particularly the part that begins in the late 1700s. In 1788, to be precise, the British founded New South Wales ... and they founded it as a prison colony. Mad Max? That was almost non-fiction.

The area functioned as a prison state for the next eight decades, and over the course of that time, around 160,000 convicts were sent there. The effects have been long-lasting, and according to the BBC, about 20 percent of today's Australians can trace their roots back to a convict marooned there by the British. That includes their former prime minister, Kevin Rudd. His family goes back to his great-great-great-great-great-grandmother, who had been sentenced to life in Australia's penal colonies when she was just 11 years old. The crime? Robbery.

Australia has always had a bit of a conflicted relationship with its convict past. According to The Conversation, it's gone from shoving aside thoughts and memories of their ancestors to talking about them with a sense of pride. Because it wasn't just a case of "we're going to send all these murderers to Australia," it was much more complicated than that. But no matter how you look at it, life in the Australian penal colonies was incredibly messed up.

Why was Australia made into a penal colony in the first place?

The run-up to Australia's time as a penal colony is a pretty interesting era, and it wasn't just a matter of the British seeing the massive island and thinking, "Hey, we know what we can do with that!" They were actually in the middle of a major crisis.

For starters, it was a time of incredible advancement over in Great Britain, particularly in the agricultural sector. But with farming getting increasingly more mechanized, fewer people were actually needed to work on the farms, and that put a lot of people out of employment. Those people headed to the cities, where they found life wasn't really any better. In turn, that led to a lot of people turning to a life of crime to support their families, and according to the Sydney Living Museums, a lot of that crime was pretty petty. It was stuff like stealing livestock and filching apples, and this petty crime was so widespread that prisons filled up.

Incredibly, minor crimes became punishable by transportation to Australia. There was simply no room in British jails, and according to History, there was another thing at work: elitism. It was 18th-century, upper-class wisdom that criminals were irredeemable, so there was no sense in keeping them around in the hopes that they would become productive members of society.

There were a lot of crimes that could get you sent to Australia

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, British citizens needed to mind their Ps and Qs because there were a lot of reasons they could be sentenced to transportation to Australia. The State Library of Queensland has made a lot of the convict records public, and they're fascinating — if heartbreaking — reading.

First, there are some serious crimes on the list. Several hundred people were sentenced for murder and manslaughter, and everyone can agree that's legit. There are also the convicts who were sentenced for assault, "child stealing," bestiality, highway robbery, violent theft, rioting, and things of that sort.

But then, there are others, and most have to do with stealing. We're talking like stealing potatoes, corn, a cap, a gown, a hair brush, linen, "a tissue of fine silk," a shovel, a handkerchief, napkins ... the list goes on and on.

And each one has names attached to it. John Nicholls was sentenced to 50 years for stealing razors, silk, ivory combs, wig ribbon, and human hair from his employers, who were "hair merchants and perfumers." Janet Campbell was sentenced to seven years for stealing a handkerchief, shirt, and bucket. And Edward (the Younger) Cushing? He was sentenced to seven years for allowing ewes to mix with rams of a different breed of sheep.

Life was terrible from the moment you hit the seas

It wasn't just life in Australia that was tough, it was life on the high seas, too. According to the Sydney Living Museums, the largest of the prison ships used to transport convicts was around 210 feet long and could hold up to 300 convicts, in addition to the regular crew and supplies. If that sounds terrible, it was. Around 6,000 people were shipped off to Australia between 1776 and 1795, and of those, around 2,000 never made it.

Cholera and typhoid were commonplace on these ships, and it wasn't helped by the fact that in order to keep costs low, prisoners were fed pretty meager rations — usually some soup and biscuits for the day. And here's the weird thing: Not everyone who was sentenced to transportation was sent to Australia. Some were just forced to live on board the ships, which never left port in England. They would spend 10 to 12 hours a day doing back-breaking work like river-cleaning, stone-cutting, and hauling wood, while spending the rest of their sentence on the ships. Most of those ships were owned by private owners who contracted their services as convict-keepers with the government. That was eventually phased out in favor of government-run programs in 1814, but still, keeping costs low was key.

The First Fleet was ill-prepared for Australia

In 1788, 11 ships sailed into the waters off Australia, all ready to found a brand new penal colony. Six of those were convict hulks, three carried supplies, and two were navy escorts. When the 1,000-odd people made it to shore, what they found was a whole lot of nothing.

According to the Sydney Living Museums, the First Fleet was ill-prepared for what they found and what they had to do — starting with building a settlement from the ground up. Convicts lived in makeshift shelters while they quarried stone, chopped trees, dug clay, and laid out roads. And for the first few years, there was a constant suspicion of those who were living nearby. Local Aboriginals kept their distance after a deadly smallpox outbreak, and in 1790, a confrontation with a predictable outcome led to unpredictable results. Aboriginals shot and wounded the First Fleet commander, and from there on out, things were sort of all right.

But there were still a ton of problems. The convicts didn't make willing workers, and theft, unrest, and drunkenness were commonplace. Then, factor in the idea that farming is harder than it looks and that rations weren't just dwindling, they were rotten and rat-infested. Violent outbursts were common, attempts to reach China for a re-supply run failed, and it wasn't until 1792 that buildings began to take shape, people settled into jobs they were good at, and things started looking up ... in spite of the near-constant threat of war and rebellion from nearby Aboriginal peoples.

New Zealand sent their 'criminals' there, too

Convicts who found their way to the penal colonies of Australia weren't just from the UK and Ireland. They were sent there from New Zealand, too. New Zealand became a British colony in 1840, and by 1843, they were shipping their convicts off to Australia. Here's the troubling part, though: They were sort of playing loose with the definition of "convict."

According to Kristyn Harman of the University of Tasmania (via The Conversation), there were a lot of murderers and thieves who were sent to Van Diemen's Land (aka Tasmania), but there were a lot of people sentenced to transportation for the crime of resisting British colonization. Some of the biggest and bravest among the Maori warriors were sentenced, as a way of sending a very clear message to anyone else who considered rebellion.

There was another group who was sent into exile right alongside those warriors, and those were the British redcoats who'd deserted — most, after realizing what terrifying warriors they were facing. Others got out of fighting another way. Striking a superior officer was, of course, an offense punishable by transportation, so some would go that route, instead. While deserters were sometimes captured and returned to their units by Maori friendly to their colonizers, giving your commanding officer a quick smack with the butt of a rifle was guaranteed to get you out of harm's way.

There was no age limit in the penal colonies

When it came to whether or not transportation was on the table for convicts, the answer was "yes," regardless of their age. And when it came to life in the colony, children got no special treatment. Both boys and girls as young as nine years old were sent packing to Australia — with or without adults to help them along. According to Sydney Living Museums, kids needed to make their own way in the world, find their own place to live, and work just like everyone else. When they arrived, they were given a single change of clothes, a hammock in workhouse barracks, and a place on a gang who headed out to their work site from breakfast to sunset.

Things went in the other direction, too. In 1787, Dorothy Handland was put onto the Lady Penrhyn and sent off to New South Wales, where she arrived in January 1788. She was serving a seven-year sentence for perjury ... and was 82 years old when she set sail. According to the State Library of Queensland, it's unclear what happened to her. While she was the oldest convict in her fleet, sources vary as to her fate. Some claim she hanged herself in 1789 and was Australia's first suicide, while others suggest she served her time and was sent back to England in 1793.

The ship that became known as the 'floating brothel'

PBS says that when the First Fleet — the English ships that kickstarted Australia as a penal colony — got to the Land Down Under, they found out real quick that they were missing a few key things: fresh water, shelter, and women. In order to fix the last thing on the list, it was decided that a ship full of female convicts was going to be sent immediately, in order to "promote a matrimonial connection to improve morals and secure settlement."

In other words, the 225 women loaded on board a ship called Lady Juliana were essentially being sent overseas as "breeding stock" that would prevent the men already there from partaking in "gross irregularities," as they'd already been found to be doing. That's not the whole story, though.

Around ten months after the ship left England, it reached Australia ... and it was carrying a few more babies than it had been when it left. It was dubbed the "floating brothel," and the women — many of whom were prostitutes or thieves by trade — had been busy earning money that they saved to give themselves a bit of a head start on life in Australia. Most, says News.com.au., were pregnant when they arrived or had just given birth.

And they were absolutely not a welcome sight. Starving convicts and settlers alike had been expecting a ship carrying supplies, not more mouths to feed. Fortunately, supply ships arrived just three weeks later, and suddenly, having some women around wasn't such a bad thing after all.

The 'Sydney Slaughterhouse' was a hospital

The building called the "Sydney Slaughterhouse" didn't involve meat at all ... well, not the kind of meat you'd want to eat, at least.

According to the Sydney Living Museums, it was officially called the General Hospital or the Rum Hospital, because it had been paid for with an exchange on the exclusive rights to import 45,000 gallons of rum into the colony. And it was a gruesome place.

This was, remember, a time when medical treatments were incredibly bizarre and still involved things like "copious bleedings." Bloodletting was still prescribed for a lot of sicknesses, as doctors were still operating under the impression that illnesses were usually caused by an imbalance in the body. And speaking of operations, when they had to do one of those, there was no anesthetic, and it was performed in the surgeon's quarters.

Hospital surgeon William Redfern left behind some fascinating documents, in which he described treatments like rubbing sores with a live toad and treating cancer with a poultice of figs boiled in milk. Presumably, that was as successful as his recipe for creating gold. And given that injuries were common and sometimes horrific — explosives are dangerous, after all, and floggings needed to be tended to after they were handed out — it's not surprising that those relying on the hospital dreaded going there.

The Australian penal colony was bad ... and Norfolk Island was worse

In 1824, the British Government came up with a solution to a very important problem. What do you do with criminals who continue to be terrible even after they've been sentenced to a lifetime of transportation? Well, you turn Norfolk Island — a tiny dot of land off the cost of Australia — into another prison colony.

According to Norfolk Online, it was the place where people were sent "forever to be excluded from all hope of return." Life was awful there, days were filled with hard labor, and punishments could be as many as 500 lashings. And all the convicts held there weren't the worst of the worst, irredeemable souls. They were also Irish.

According to The Irish Times, Norfolk was the first destination for Irish rebels, and when writer Robert Macklin did a deep dive into the island's history, he found that the local who'd told him "Satan lives here" had it right. In addition to the horrors everyone was subjected to, there was another footnote for Irish prisoners. If ever a non-British ship was seen approaching, Irish prisoners were herded into a wooden stockade. If the ship landed, the stockade was set ablaze, because the British knew that if there was any conflict, the Irish would be the first to turn on them.

Daily life was so bad that many Catholic prisoners resorted to committing crimes they would be executed for. After all, their faith kept them from suicide, but still ... they needed a way out.

Some went deeper down the rabbit hole of crime

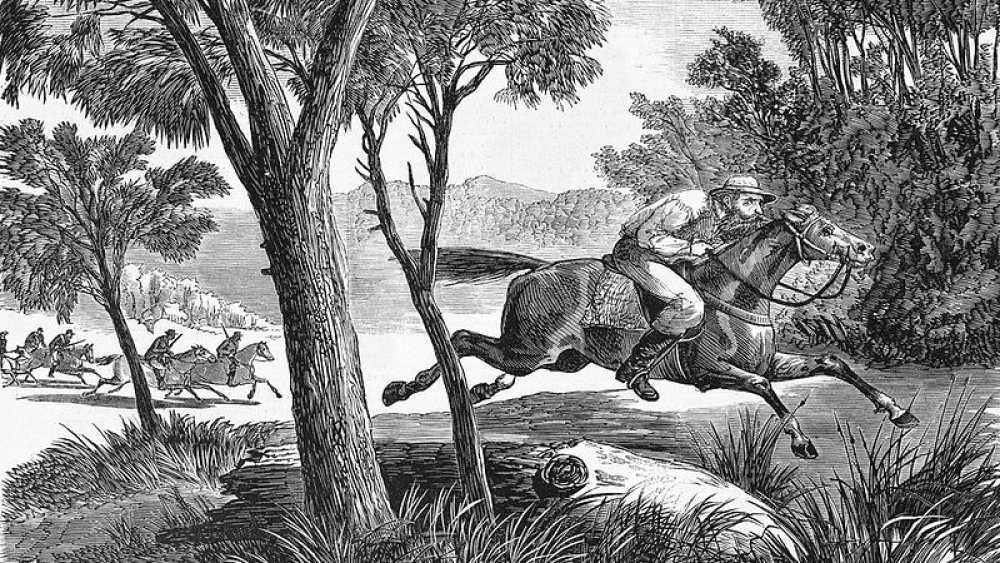

When it comes to pop culture, Australia's bushrangers exist somewhere between Robin Hood and the outlaws of America's Wild West. But as for the truth? Well, that depends.

According to Australian Geographic, most of the era's bushrangers were British and Irish convicts who'd gotten tired of the hard labor that came with their sentence of transportation, so they escaped into the Australian bush. The first, says National Geographic, was thought to be John Caesar. He adopted the nickname "Black Caesar," but for the most part, he made his way through life by hunting, fishing, and making friends with the locals. But others weren't nearly so nice.

Take Alexander Pearce. When he was captured, he had some "human flesh" in his pocket. Eventually, he was hanged for cannibalism. Dan "Mad Dog" Morgan (pictured) liked to torture the people he killed, and he once shot a man who said hello to him. "Brave" Benjamin Hall rode at the head of a gang who committed more than 100 armed robberies, but they never killed anyone. Neither did Martin Cash, the "Gentlemen Bushranger," who stole from the rich and died a peaceful death at age 69.

Then, we can swing back the other way to Charles "Black Douglas" Russell, who liked to tie up his victims then fill their boots with fiery bull ants — not a pleasant way to die at all. Strangely, bushrangers one and all have become something of a symbol of Australia's national pride ... usually, without mention of the bull ants.

The children of convicts grew up to be taller than their UK-based peers

When we think of the convicts sent to serve their time in Australia, we think of people sent to live a very, very hard life, indeed. But some research suggests that they may have ultimately been better off than those who stayed behind in Great Britain.

The Digital Panopticon project looked at the lives of tens of thousands of convicts, many of whom stayed in Australia and started families there. They found (via The Conversation) that the children of those convicts were, on average, more than four centimeters taller than their parents, whether they had come from Britain or Ireland.

They chalk this up to a few things. Because so many people had died on the first few voyages, it was only the hale and hearty who were actually sent overseas on later ships. In other words, those who survived were pretty tough and had overall good health.

But they also say that in many ways, life in Australia was better — and more conducive to a healthy lifestyle — than life in the crowded cities of Britain. The air was fresher, the water was cleaner, and food was more abundant and higher in protein. Also, women weren't allowed to have kids until they'd finished their sentence, and they generally had fewer offspring. The result? Taller, tougher, healthier children.

The story of Australia's last surviving convict

The idea that Australia served as a home to Britain's unwanted sounds like something that happened ages ago, but in the grand scheme of things, it wasn't that long ago. According to the University of Liverpool (via The Conversation), the last ship to take convicts to Australia docked in 1868. For perspective, that's just a few years after the end of the American Civil War. A long time ago, right?

That makes it even stranger that the last living convict only died in 1938 — at the eve of World War II. His name was Samuel Speed, and he'd been born in Birmingham in 1841. A very young Speed had been living in Oxfordshire when — homeless — he set a haystack on fire. He'd been hoping to get arrested and to spend the night in the warmth of a jail cell. Instead, he was sentenced to seven years transportation and was shipped off to Australia in 1863.

Speed's story was unusual in that it has a happy ending. He was released on something like probation in 1869, earned his full freedom two years later, and went on to become a bridge-builder. He never got in trouble again ... unlike an estimated 80 percent of those who arrived on that last ship in 1868.