The Incredible Life Of The Real Sherlock Holmes

Back when Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was writing and publishing the stories that would later help Benedict Cumberbatch elicit swoons as the slim and sexy sociopath, the inspiration for Doyle's most prominent creation was alive and well. Sherlock Holmes may have inspired thousands of detective stories and fan clubs around the world, but who was the sleuth that inspired this seemingly superpowered genius of investigation? Well, he wasn't really a detective at all, not in his everyday profession anyhow.

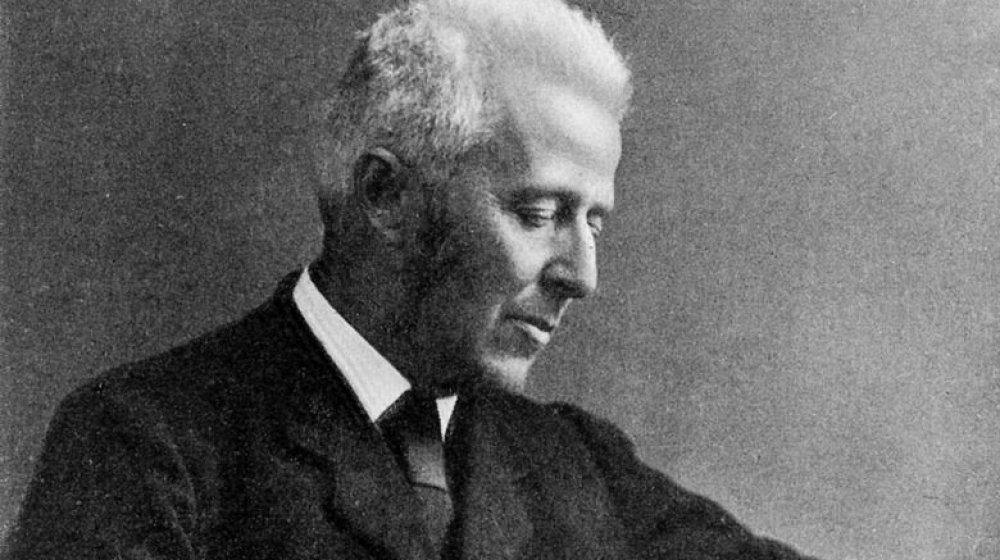

He may not have looked anything like Robert Downey Jr., but Dr. Joseph Bell was similar to Doyle's legendary hero in many ways. (Though, from what we can tell, he probably didn't share Sherlock's classic opium addiction.) Both Holmes and Bell had immense powers of observation and deduction, but where Sherlock Holmes used his gifts primarily for his detective work, Dr. Bell used his skills first and foremost for medicine. Joseph Bell was many things to many people, and being a part-time detective is only part of his story.

The early life of Dr. Joseph Bell

Bell was born in 1837 and raised in Edinburgh, Scotland at a time when his strict religious upbringing would seem very normal. Thanks to his father's involvement with the Free Church, which had no ties to the state or government, Bell and his siblings were well-educated in all things Biblical. Bell's affinity for the church would continue throughout his life and later influence his charitable works.

As a young student, Bell was that kid who never got into trouble and always excelled in his studies. His studious nature is what allowed him to make it through the class of one James Gloag, a math teacher at Edinburgh Academy who had a penchant for beating his students with a type of leather whip known as a "tawse," according to The Real Life Sherlock Holmes: A Biography of Joseph Bell. It seems Bell was rarely a target of Gloag's.

Bell came out on the other side with a well-formed education, including several languages, and an extensive athletic resume that would turn into an intellectual love of boxing later on. Think Robert Downey Jr.'s Sherlock minus all the "ouch."

Surgery was Joseph Bell's real calling

Joseph Bell enrolled in medical school at the University of Leiden when he was just 17 years old. It was a renowned school that educated the likes of Rene Descartes and John Quincy Adams, but Bell left early due to a serious case of homesickness. He gave it a second go at the University of Edinburgh, where he graduated at just 22, according to National Galleries Scotland. This in itself is one heck of an accomplishment, although most people would have a hard time trusting a 22-year-old to cut them open and put everything back in the right spot.

After medical school, Bell quickly gained popularity in the surgical community. He published several texts on medicine and practiced as a senior surgeon at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh before becoming the first surgeon at Edinburgh's Royal Hospital for Sick Children. It isn't too surprising that Bell went down this road: Surgery was in his blood. Bell's father, grandfather, and great-grandfather were all accomplished surgeons.

From surgeon to teacher to becoming Sherlock Holmes

During the course of Bell's medical work, he would become a professor of medicine at the University of Edinburgh. It was here, in 1876, according to National Galleries Scotland, that a certain student would walk through the doors expecting to graduate and live out his life as a surgeon, but that's not what fate had in mind. The student would instead meet Dr. Joseph Bell and have his future and the world of literature change forever. That student was Arthur Conan Doyle.

Bell was known for teaching observational methods as an important part of medical diagnosis, believing that using your senses could tell you as much, if not more than, asking questions. Also he was really, really good at it. Further, he'd teach the power of imagination as a way to weave observations into theories. He enjoyed using his deductive and reasoning skills to impress his students by giving them patient histories that he seemingly pulled out of a hat. It was these skills, and his reported cold and calculated demeanor toward patients, that would be the basis for Sherlock Holmes, according to Stanford University.

Even Queen Victoria was impressed by the real-life Sherlock Holmes

It's not every day that someone impresses Queen Victoria. That could be because she's been dead for quite a while now, or it could be because impressing a queen isn't an easy feat. But then again, Bell wasn't your average Joseph. He was so renowned as a surgeon that he would later become the queen's personal surgeon anytime she visited Scotland, according to Edinburgh Live. But that's not really where this story starts.

In the 1860s, there was an outbreak of diphtheria in Britain. One of the symptoms of the disease is gross, puss-filled pockets in the throat, and doctors didn't have a way to deal with it at the time. So Joseph Bell invented a special pipette to suck away the diseased material. While treating patients during the epidemic, Bell contracted the disease himself.

The stories of Bell's courage during the outbreak later prompted Queen Victoria to visit him and to rename his hospital ward "The Victoria" in his honor, because that's how honor works sometimes.

Joseph Bell was Sherlock Holmes, and Conan Doyle was Dr. Watson (ish)

We've established that Joseph Bell was the inspiration for Sherlock Holmes, but we haven't discussed Dr. Watson at all. Dr. John Watson, Sherlock's fictional sidekick and scribe of his tales, was played by Arthur Conan Doyle, for a while at least.

In Doyle's second year of medical school, Bell hand-picked him to work as his medical assistant in Bell's ward, according to Conan Doyle Info, which gave Doyle more than ample opportunity to study Bell's personality and methods closely. Doyle would take Bell's belief that observation was the key to being a good physician and to coming up with an accurate theory or diagnosis, and stow it away for future use as a character we know and love. Just as Watson took notes on his boss, Sherlock Holmes, and later whipped the notes into grand adventures, so Doyle took notes on Joseph Bell. When he later turned these observations into the Sherlock Holmes stories, Doyle essentially became Watson in real life.

Sherlock's (Bell's) powers of observation revealed

What Joseph Bell did with observation, many would believe to be magic or perhaps that Bell was a magician of the David Copperfield variety. He could seemingly tell you a person's life story from across the room, but according to Mount Sinai Journal, it wasn't magic at all.

Bell would teach his students to use their eyes, ears, brain, perception, and deductive skills to piece "a broken chain" together or to untangle a web of clues. It was common for the doctor to show off in his classroom by inviting patients to be a sort of subject for him to decode. He would study the calluses on a patient's hand to deduce the type of manual labor he worked, notice small bumps in a breast pocket where an alcoholic was hiding his liquor, and, according to Conan Doyle Info, hear the smallest change in inflection — something he had trained himself to do over the years — to deduce a patient's place of origin.

So where Joseph Bell's and Sherlock Holmes' observational methods seem mysterious, they aren't anything more than the observing of small details, a broad knowledge of, well, everything, and the brainpower to fit the pieces together.

Investigating was only Joseph Bell's side job

We've established that Joseph Bell was a surgeon and a teacher, but we've talked very little about his detective work, mostly because it wasn't a big part of his life. Unlike the infamous Sherlock Holmes, whose investigative work was the mainstay of his identity, Bell's time as a detective was only a part-time gig. There weren't cameras on street corners or FBI databases full of DNA sequences in the 1800s, so the police in Edinburgh had to use old-fashioned deduction. And Joseph Bell was one of the best. According to Mount Sinai Journal, Bell rather enjoyed detective work and fancied himself an amateur investigator.

When Bell worked on crimes, they were usually major crimes and he was usually working alongside the police doctor Sir Henry Duncan Littlejohn. While working with Littlejohn, Bell had been involved with the case of Elizabeth Chantrelle's murder in 1877 and the Ardlamont mystery in 1893. Littlejohn and Bell found that Chantrelle, "thought to have died of gas inhalation, had in fact been poisoned by her husband," according to Scottish Field. In the Ardlamont case, Littlejohn and Bell discovered that a suspected suicide was actually a murder, but prosecutors couldn't secure a conviction against the suspect. Unless you're a serious Victorian history buff, you probably haven't heard of these cases, but don't worry — he also worked on the Jack the Ripper case.

Joseph Bell was one of the earliest pioneers in forensic science

Like Sherlock Holmes, Joseph Bell was an early pioneer in forensic science and, more specifically, forensic pathology. Bell used observational and scientific methods to find evidence at crime scenes and when examining the corpses of murder victims. He was able to find facts, which he would use to formulate theories. It sounds like common sense now, but that wasn't how most investigations worked during the late 1800s and early 1900s — well, not until pioneers like Joseph Bell got on the scene. It was more common for detectives to begin with a theory, then twist the facts to fall in line with their theory.

According to Crime Traveler, a criminology resource website, Bell is one of the fathers of crime scene forensics. He was one of the first people to bring scientific observation into police work, opening people's minds to what was possible with a better scientific method. Before forensic science, a court would need a confession of guilt or eyewitness testimony to convict a suspect. Crime Traveler also claims the stories of Sherlock Holmes did a lot to further forensic science by highlighting Bell's techniques and increasing his popularity.

Joseph Bell's involvement in the Jack the Ripper Case

The case of Jack the Ripper was filled with brutal killings that confused and frustrated investigators to the point that Scotland Yard began to enlist help from detectives around the United Kingdom, Joseph Bell and Sir Littlejohn included. In this case, the two doctors didn't work together but instead conducted two independent investigations. As Bell put it, "When two men set out to investigate a crime mystery, it is where their researches intersect that we have a result." And, this is where the conspiracy buffs get interested.

You know how the Ripper case never got solved? Well, it actually might have been solved, but no one alive today has evidence to prove the identity of the killer. According to Scottish Field, Bell and Littlejohn may have cracked the case. They say that at the end of both doctors' investigations, the pair met to exchange the name of their suspect by writing them down and exchanging names. And they supposedly both wrote the same name. Scottish Field notes that the murders stopped soon after and nothing seems to have come of their investigation.

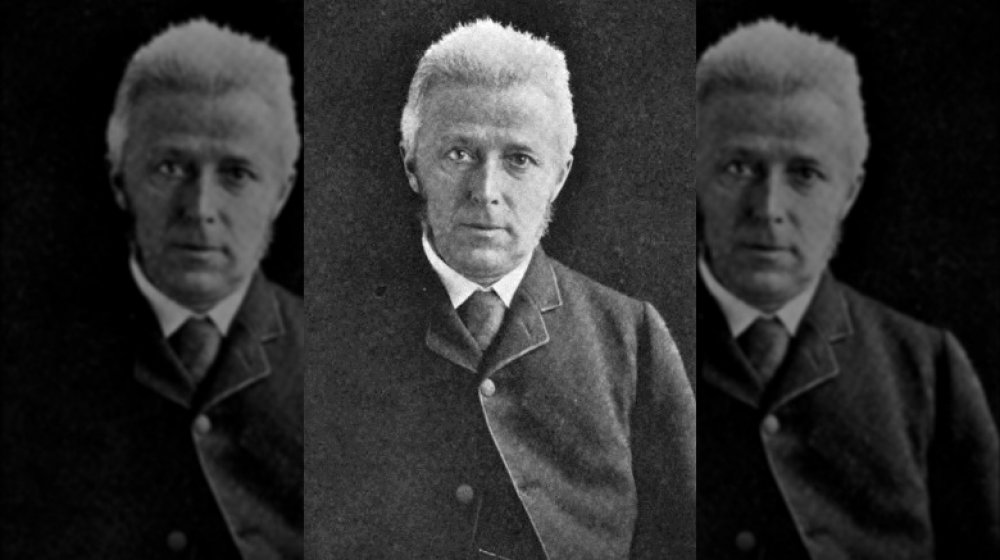

Joseph Bell didn't like the publicity Sherlock Holmes brought him ... at first

During the beginning of Sherlock Holmes' literary life, when Joseph Bell's friends and Edinburgh locals were making some "elementary" deductions of their own, Bell was getting slammed with the type of local fame and publicity that no busy person wants in their life. Every new journalist who wanted an interview added to Bell's annoyance. According to Scottish Field, Bell had claimed: "I am haunted by my double, Sherlock Holmes."

The irritation ran deep. Bell once wrote to a friend, according to Mount Sinai Journal, to call Doyle's stories "cataract of drivel" and to state Doyle never thought "such a heap of rubbish" would fall on Bell's head due to the stories he'd published.

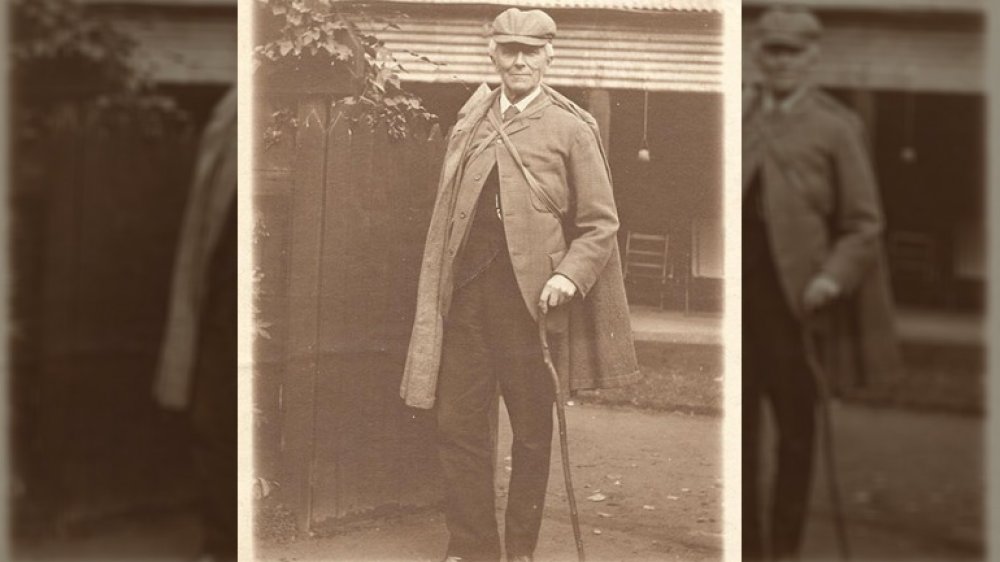

But this was in the early years of Sherlock Holmes. After a while, Bell grew more attached to Doyle's character, believing it led people to think and observe — two skills he believed were lacking for most people. By the end of his life, Bell had gotten over the publicity and was even pitching story ideas to Doyle. There's even a surviving photo of Joseph Bell in Sherlock Holmes' traditional deerstalker hat and cloak, above.

Joseph Bell was ahead of his time in supporting women's rights

In the political landscape of the late 1800s, right around the time of the women's suffrage movement in America, the real-life Sherlock Holmes was well ahead of the game in supporting women's rights. He adamantly campaigned for women to be admitted to medical school, according to National Galleries Scotland, unheard of at the time. Bell even wrote a helpful manual titled Notes on Surgery for Nurses, one of the earliest medical texts for nurses. He dedicated it to his friend, Florence Nightingale.

Joseph Bell was also a key figure and founder of the Queen Victoria Jubilee Institute for Nurses in Edinburgh, where he held the office of vice president. Though controversial at the time, Bell agreed to formally teach medicine to female students, according to Scottish Field. This lined up pretty well with his support of women's suffrage, which was also controversial at the time.

Joseph Bell was good friends with Florence Nightingale

Thanks to Joseph Bell's relatively progressive views, according to Scottish Field, his work would lead to a close friendship with Florence Nightingale. Nightingale created the philosophy of care and comfort that would be the foundation for modern nursing, as Britannica recounts. In 1860, the Nightingale School of Nursing, the first science-based school for the profession, opened in London.

Nightingale was famous for her work on social reform and the reformation of nursing. She enjoyed long walks on the ward at night and checking on patients during "rounds" with an old-timey oil lamp, earning her the name "Lady with the Lamp." Essentially, she was a big deal in the nursing world. Nightingale and Bell made friends while he was helping to organize a series of medical lectures for nurses. The two were known to correspond by letter frequently. In one, Nightingale personally thanked Bell for dedicating his medical manual for nurses to her.

A surgeon with a literary career

Sure, Joseph Bell didn't write the sort of fiction that would bring him oodles of fame like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle did, but he had a literary career of his own, mostly in the field of medicine. Joseph Bell's books, being what they were, did fairly well. Notes on Surgery for Nurses would be a best-seller through the 1890s, according to The Queen's Nursing Institute Scotland, and his Manual of the Operations of Surgery would manage to run seven editions. Bell would also author several medical theses and other articles on non-medical topics throughout his life. He even worked as Edin Medical Journal's editor for a solid 23 years.

Bell also wrote poetry, according to The Real Life Sherlock Holmes: A Biography of Joseph Bell, mostly dabbling in poems regarding nature or inspired by religious themes. Poetry never really became part of Bell's money-making career, but with all of the other accomplishments under his belt, we can probably forgive the real-life Sherlock Holmes for not becoming a world-renowned poet as well.