The Tragic Lives And Deaths Of Jack The Ripper's Victims

Generally, we tend to look back on Victorian England with a sort of wistful nostalgia. It was the stuff of A Christmas Carol and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. It was a time of scientific advancement, of a blossoming cultural landscape, and British domination on a global scale.

But it was also a dark and dismal place, particularly in London's East End. While the "haves" were proudly proclaiming the might of the British Empire — and reaping the rewards — just three miles from the lavish West End was Whitechapel. There, thousands of people lived amidst disease and poverty, scraping by with what meager living they could make. The two worlds rarely collided, and even the Diocese of London called it (via National Geographic) an area that was "as unexplored as Timbuktu."

And then Jack the Ripper showed up.

When the first body was found on August 31, 1888, it did something unexpected. The extreme violence and the horrible, grotesque things done to the bodies kicked off a wave of unrest. The well-to-do Londoners were suddenly forced to look to the east and acknowledge their poverty-stricken neighbors. It fueled the fire of racial and class conflict, stumped the era's best and brightest detectives, and remains one of the world's most well-known cold cases. Everyone knows the name Jack the Ripper ... but what about the names of his victims? Who were these poor women? Well, today, we're taking a look at the tragic lives and deaths of Jack the Ripper's victims

Mary Ann 'Polly' Nichols was the first canonical Jack the Ripper victim

It's been long debated just when Jack the Ripper started killing, but the first victim that isn't disputed is 43-year-old Mary Ann Nichols. She was better known to her neighbors as Polly, and she didn't have an easy life. She was born the daughter of a blacksmith, and she married a printer named William Nichols. Five (some sources say six) children later, though, they split up. William had decided to hook up with a neighbor instead, and during the 1880s, Polly found herself living on the streets of London.

By then, she'd already started down the path to alcoholism. She drifted from workhouse to workhouse, occasionally into infirmaries, and sometimes she resorted to sleeping in Trafalgar Square. In 1888, she gravitated toward the East End, and when she could afford it, she opted for getting a bed in an area lodging house. On the night she was murdered (via The History Press), she'd actually earned enough money to pay for a bed ... but drank it away, instead. At 2:30 AM, an acquaintance saw her stumbling through the dark, early morning streets. She was so drunk she was having difficulty walking, and just an hour and 15 minutes later, two men discovered what they thought was a pile of bloody rags.

It was Polly, and according to the Oxford University Press Blog, she was found on August 31, 1888, in a narrow alley called Buck's Row. She'd likely been strangled before she was killed, and her throat had been cut, her genitals mutilated, and her abdomen sliced open. There was actually a suspect, a slipper maker named Jack Pizer, but the man known as "Leather Apron" was eventually cleared, and the killing continued.

Annie Chapman had a hard life and a terrible death

Annie Chapman — the second victim — started out fairly well-to-do, at least compared to Jack the Ripper's other victims anyway. She was born into a working-class family, and as The Guardian explains, since her father was in the army, she started out life in "the better parts of London." But tragedy struck when she was young. In 1844, she saw four of her five siblings die thanks to scarlet fever and typhus, over the course of just three weeks.

Still, she married well. John Chapman was a gentleman's coachman, and their combined earnings meant they had a comfortable home and could afford to educate their three children. It sounds brilliant on the surface, but she soon saw the same tragedy she'd suffered through with her siblings hit her own children. Their 12-year-old daughter Emily Ruth died in 1882 after succumbing to meningitis, and their son, John Alfred, was born with a disability that required special care. He was sent to a charity school, and both Annie and her husband descended into alcoholism. Even as their other daughter left home to join what Whitechapel Jack describes as a "traveling ... performance troupe in France," John died of cirrhosis in 1886.

And so Annie found herself alone and on the streets. She made what little money she could by selling flowers and crocheting. After drifting through different lodging houses, she was eventually given a regular place to stay thanks to a man named Ted Stanley. Her last hours are debated, but it seems she got into a fight with another lodger and headed out into the streets. She was found on September 8, at No. 29 Hanbury Street, and she was so mutilated that the medical examiners left out the worst of the details at the inquest.

Elizabeth Stride had fallen on difficult times

According to Casebook, those who knew Liz Stride described her as a kind soul who would do a "good turn for anyone." But she, too, had fallen victim to hard times.

Stride wasn't English. She'd been born in Sweden and worked there as a domestic servant. In 1866, she moved to a Swedish parish in London, and got a job working for a family in Hyde Park. Three years later, she married John Stride and together, they opened a coffee shop. Even though she frequently claimed to have been on the SS Princess Alice when it sank in the Thames — and that she lost her husband and children in the accident — there's nothing that suggests that was the truth. John Stride actually died in 1884, and it wasn't long before Liz Stride's life dissolved into episodes of drinking, fighting, and being dragged before the local magistrate.

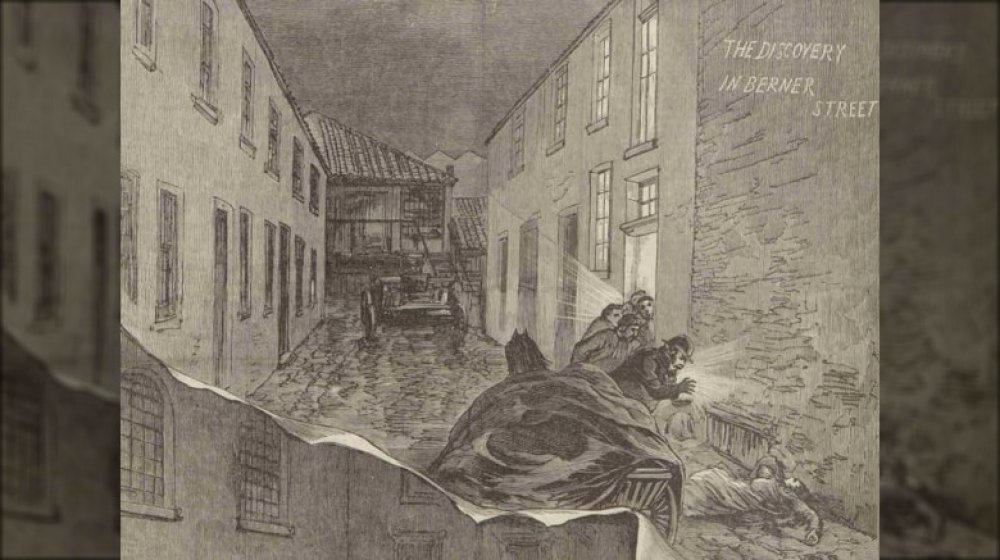

By 1888, she was earning a bit of cash cleaning rooms at a Flower and Dean Street lodging house, and she hooked up fairly regularly with a man named Michael Kidney. He last saw her five days before her body was discovered, and while multiple people claimed to have seen her in her final hours, witness reports range from contradictory to unlikely. What's known is that she was discovered at 1 AM on September 30, in Dutfield's Yard by a jewelry salesman. His pony refused to go into the yard, leading him to believe that not only had he interrupted the murderer, but that the Ripper was probably still there when he found her. Her throat had been cut, but she hadn't been mutilated as the others were.

Catherine Eddowes lost her life ... and an important organ

Sometimes she was called Catherine, sometimes Kate, and sometimes Kate Kelly, but regardless of what name she gave, it was her kidney that was sent to George Lusk in October 1888. When Police Constable Watkins found her body in Mitre Square on September 30, he found a gruesome sight. Her throat had been cut, her face sliced, and she'd been disemboweled, with her intestines arranged around her body. And, of course, a kidney had been removed.

It was a horrible end for the woman described (via Whitechapel Jack) as scholarly, intelligent, and as a "very jolly woman, always singing."

Catherine Eddowes was born in Wolverhampton, and she was educated at St. John's Charity School and then Dowgate Charity School. By the time she turned 21, she was still in Wolverhampton and involved with a military man named Thomas Conway. They didn't marry, but they lived together for almost 20 years, had three children, and made their living by writing and selling cheap books and songs known as "gallows ballads." They ultimately split because of her drinking problems, and she ended up at Cooney's Lodging House on Flower and Dean Street. She made her living doing odd jobs wherever they were needed, and she also regularly got work in the countryside picking crops.

In fact, Eddowes — along with her partner, John Kelly — had just returned from the countryside when she was killed. They'd had no luck getting work picking hops that year, and they walked back to London. By the time she died, all of Whitechapel was on high alert. Kelly warned her to be cautious, and her last words to him were, "Don't you fear for me. I'll take care of myself, and I shan't fall into his hands."

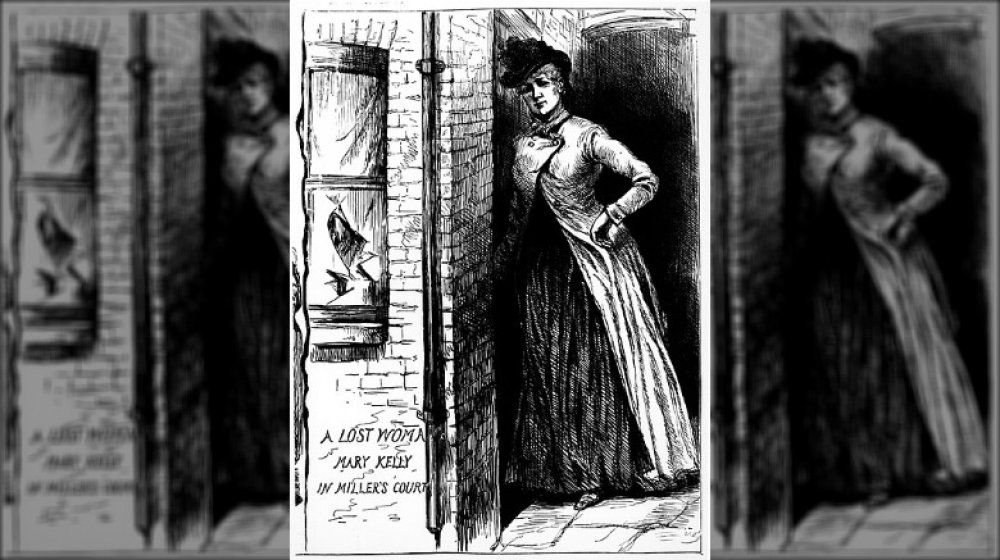

Mary Kelly was well-liked and horribly murdered

It was November 9, 1888, and when Thomas Bowyer, shop assistant to the landlord she was renting from, was sent to collect Mary Kelly's past rent, he found broken windows and (via Whitechapel Jack) what looked like lumps of meat on the table bedside her bed. Those "lumps" were parts of Kelly, and her body was only identifiable by her blonde hair and her eyes.

Much of Kelly's life is a mystery, told and retold by her partner, Joseph Barnett, and the scores of friends she made across the East End. She was — they said — born in Ireland but grew up in Wales, and there were hints that she was from a very well-off family. Those who knew her best said she was well educated and artistic, but life hadn't been kind. When she was just 16, she married, and three years later, her husband was killed in a mine explosion. From there, she headed off to Cardiff, then made her way to London, finally landing in a high-class brothel in the West End. After a brief trip to Paris, she was back in London, and this time, living in the East End.

There, she had the now familiar host of problems. She was fined several times for drunk and disorderly behavior, but at the same time she supported herself mainly by prostitution, she regularly shared her small room with other girls who had nowhere else to go. It was Catherine Pickett, a friend of Kelly's, who summed her up like this: "She was a good, quiet, pleasing girl, and was well-liked by all of us."

Was Martha Tabram actually the first of Jack the Ripper's victims?

There are a lot of unknowns when it comes to the Jack the Ripper case, and one of those is how many people did he actually kill. There's a whole slew of potential victims, and while many have been written off by most scholars, there's one that's worth mentioning: Martha Tabram. She was killed in pre-dawn hours of August 7, 1888 (via Jack the Ripper 1888), and even though she was of "the lowest class," papers still struggled with reporting the brutality of the murder. She was stabbed 39 times, with all her wounds across her torso — the Ripper's favorite part of the body.

So, who was she? She, too, suffered from some extreme misfortune. She married a foreman furniture packer named Henry Samuel Tabram in 1869, and they moved right into their new home. Two sons quickly followed, but so did alcoholism. Henry left because of her drinking, and although he continued to support her with a weekly allowance, her constant need of more money — and her moving in with another man — led to him cutting her off. According to Casebook, her constant drinking only got worse, and she funded it with the occasional bit of prostitution and by selling trinkets. On the night she died, she was last seen in the company of two men that she and a friend had met in the Two Brewers pub. After pub crawling a bit and escorting them into an alley, she was later seen "sleeping" on a landing in the George Yard Buildings. She wasn't sleeping.

But they were all prostitutes ... right?

If there's anything most people know about the victims of Jack the Ripper, it's that they were all prostitutes ... right? Absolutely not, says historian Hallie Rubenhold (via The Guardian). She did a deep dive into the lives of the five women killed by the Ripper, wanting to make them more than just victims. And as she explained, "The more I looked for evidence of sex work, the more I found that it just simply wasn't there. What I found instead was a lot of convoluted, confused definition of what prostitution was among the working classes and the poor. It is ... totally at odds with what we call 'Victorian morality.'"

In her research, she found that only two of the Ripper victims — Stride and Kelly — actively worked as prostitutes. More often, even though they were down on their luck and living rough, the others eked out a living by taking on work as domestic servants or in laundries.

So why does everything think they were prostitutes? A big part of the reason is how they were viewed in life. They were poor, they were scraping by to make ends meet, and they were often living on the streets. As far as high society was concerned, that all pretty much just made them prostitutes. Rubenhold makes another point, too. If people could somehow convince themselves the women had been asking for their deaths, it would make the crimes that much easier to come to terms with.

The number of women like Jack the Ripper's victims is pretty shocking

At the time the Ripper was prowling the streets, he had an almost shocking number of potential victims. According to the BBC, the East End was home to somewhere around 78,000 people in 1888, and they were broken down into three classes: the poor (laborers and dock workers), the very poor (mostly women, making their living washing clothes, sewing, or weaving), and the homeless. Disease and hunger were so rampant that any baby born had about a 50/50 chance of living past their fifth birthday. And those lodging houses? They weren't great, but at least it got you out of the streets ... where everyone tended to dump their sewage.

However, lodging houses — like the ones the Ripper victims scrimped and saved to buy a night in — were so bad that they don't sound real. There were around 200 in the Ripper's time (via Victorian Web), and every night, they provided shelter — albeit temporary — for between 8,000 and 8,500 people. Anyone wanting one of the coffin-sized beds needed to fork over four pence. And for two pence? Each one had a rope that ran from one wall to the other, and that two pence got you a position to lean against the rope.

In 1849, The Times published a letter from the slum-dwellers in St. Giles. It read, in part (via The British Library), "We live in muck and filthe. We aint got no priviz, no dust bins, no drains, no water-splies, and no drain or suer in the hole place. ... We all of us suffur, and numbers are ill, and if the Colera comes Lord help us." In other words, Jack the Ripper's hunting grounds were a terrible place to live, and it sounds like the Victorian era was truly messed-up.