Stories From History That Ignore The Real Hero

In many ways, history is a series of stories that we tell ourselves. But while we oftentimes can't help but indulge in narratives that have clear beginnings, ends, heroes, and villains, life isn't always quite so clear. Even when there are real people doing genuinely heroic things, the unjust truth is that sometimes their stories get buried. It may or may not be intentional, but ultimately you've got to conclude that quite a lot of people were left out of even the biggest stories you learned in history class.

If you're not so sure, consider some of these questions: Who made it so we can feed our species to the point where, as of 2025, there are more than 8 billion of us? Who was one of the first people to urge doctors to clean their darn hands? Why do the gas tanks at your local filling station specify your fuel is unleaded? And, while we're asking these sorts of big-picture questions, why did people once get human anatomy so wrong, and who set about correcting our basic understanding of the human body? If you don't know the answers already, there's no better time than the present to set about fixing things and uncovering some of the ignored real heroes of history.

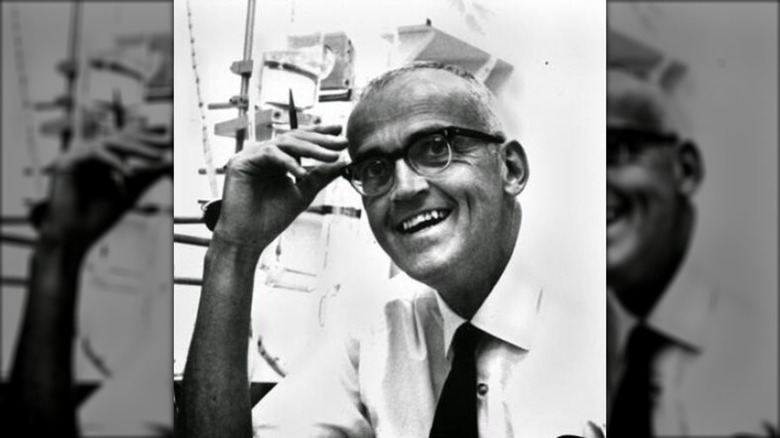

Norman Borlaug kicked off an agricultural revolution

If you ever got around to studying agriculture in history or science class, you've likely gotten a broad overview of the agricultural revolution, but you may not have heard of one particular man at the center of it all: Norman Borlaug. The Green Revolution, which saw a massive increase in crop yields and saved untold numbers from starvation, may not have happened without him. While the Green Revolution isn't without its critics (namely those who worry about its extensive use of pesticides and fertilizers), surely we agree that someone who helped millions not starve to death deserves more attention.

Initially a forestry student at the University of Minnesota, by 1944 Borlaug was a geneticist directing the Cooperative Wheat Research and Production Program, stationed in Mexico. Under his direction, its team began churning out wheat hybrids in the quest to develop an especially disease-resistant, high-yield variety. The result proved successful not just in Mexico, but also across the globe. Borlaug shared these wheat seeds with interested nations, with the stipulation that they set up research and graduate-level agricultural science programs.

For both his scientific research and humanitarian efforts to combat worldwide hunger, Borlaug was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970. Oh, and he also won the Congressional Gold Medal and Presidential Medal of Freedom, while also getting inducted into the National Wrestling Hall of Fame (he found the time to wrestle, coach, and referee while still in college).

Can you name the first known author in history?

Who was the first named author in history? You might guess Homer, but you'd be wrong. Enheduanna lived in ancient Mesopotamia more than 4,000 years ago and was the daughter of empire-builder Sargon of Akkad. The Akkadian Enheduanna was installed as the high priestess of the main temple of Ur, a city in Sumeria. As a result, Enheduanna was in a tricky situation where she had to combine Sumerian and Akkadian religious traditions while supporting her father's expansionist ventures. As referenced in one of her poems, political troublemaker Lugal-Ane temporarily forced Enheduanna into exile. In "The Exaltation of Inanna," she gives credit to the titular goddess for restoring Enheduanna back to power.

Enheduanna is credited with crafting religious hymns that influenced countless later works. Besides "The Exaltation of Inanna," her name is also attached to "The Great-Hearted Mistress" and "Goddess of the Fearsome Powers," all three of which are meant to honor Inanna (along with another 42 or so poems). Only, this wouldn't have been quite the same Inanna that the Sumerians of old would have worshipped. Part of Enheduanna's canny political and cultural work meant melding Sumerian and Akkadian deities, which kept her in power for over four decades — and established her name in history.

Nils Bohlin is still keeping you safe in car crashes

Hopefully, everyone reading this who drives or rides in a car uses their seatbelt. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration estimates that nearly 15,000 people were saved by seat belts in 2017 alone, and that between 1975 and 2017, a staggering 374,276 people were saved by seat belts. So, who's to thank?

That would be Nils Bohlin, the Swedish engineer who created the three-point seatbelt in nearly every car today. Prior to Bohlin's invention, which went live in Volvo cars in 1959, seat belts — if anyone bothered to use one at all — were a simple two-point lap belt that sometimes caused serious internal injuries in a crash. Bohlin, who had designed ejector seats for planes, was brought on by Volvo to address that problem. His goals included not just increasing safety, but doing so in a way that was convenient for users to implement. After about a year of designing and testing, the result was the three-point belt, which secured a person more effectively and was easy to use one-handed. Volvo made Bohlin's design available to other car makers at no cost. In the U.S., seat belts were mandatory parts of vehicle design from 1968 onward.

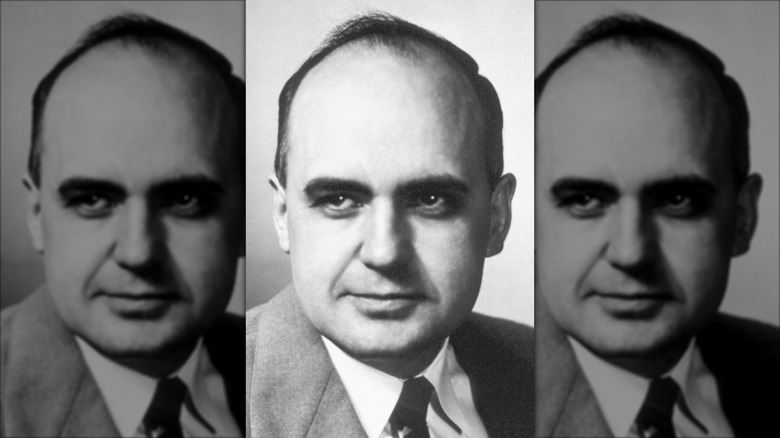

Maurice Hilleman developed vaccines and saved lives

While vaccines may be controversial in certain quarters, hard data shows that they can be powerful tools in the fight against infectious diseases. A 2024 paper published in medical journal The Lancet showed that, since 1974, vaccines have been able to prevent an estimated 154 million deaths, including about 146 million that would have otherwise taken the lives of children younger than 5 years old. But can you name some of the key people who helped implement such a major advance?

Maurice Hilleman developed over 40 vaccines, including a combined one for measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) that you likely received during your own childhood. In fact, Hilleman had a major hand in creating or markedly improving nine of the 14 vaccines that are now standard recommendations for children in the U.S. He also developed a hepatitis B vaccine that became the first known one to prevent cancer in humans. His study of how viruses mutate over several short-term generations helped prevent what could have been a major flu pandemic in 1957 U.S. (via some 40 million doses of a custom-made flu vaccine).

Perhaps you don't know much about Dr. Hilleman because he didn't tend towards self-promotion. One of the few personal touches he brought to his research was sampling the mumps virus from his own daughter, Jeryl Lynn, in 1963. He named the strain — which replaced a far less-effective vaccine – after her.

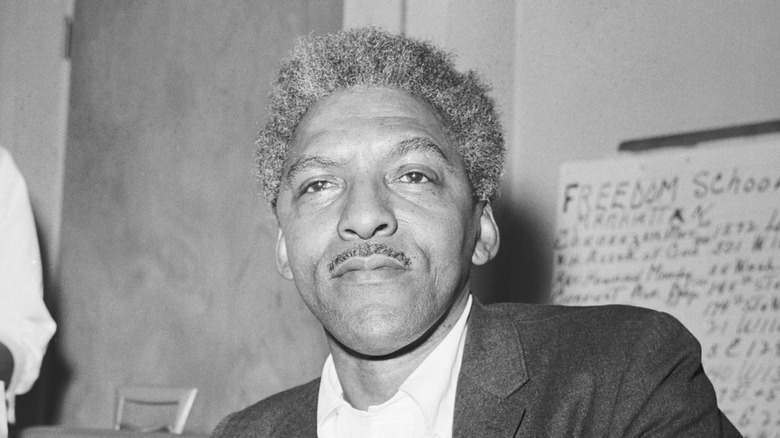

Bayard Rustin was an integral part of the Civil Rights Movement

When discussing the Civil Rights Movement, don't forget Bayard Rustin, a nonviolent activist who advised MLK and was integral to organizing the 1963 March on Washington. How was he so forgotten? For one, politics. As a young adult, Rustin joined the Young Communist League, which later turned him into a political liability as anti-Communist sentiment took hold in the U.S. (Rustin left the Communist Party in 1941). Then, there was his arrest and conviction in 1953 for "lewd conduct" with other men. As a result, he was pushed to resign from the American Friends Service Committee.

Though he continued his activist work, homophobia proved to be a serious roadblock, such as when opponents of the March on Washington attempted to start the false rumor that Rustin's complex relationship with MLK was somehow romantic. Rustin even resigned from King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference, but put aside what must have been a painful snub and came back to work for King. Still, thereafter he was often pushed to the side or purposefully left out of the narrative, for fear that political opponents would use his prior stint as a communist and ongoing life as an openly gay man against the credibility of the movement.

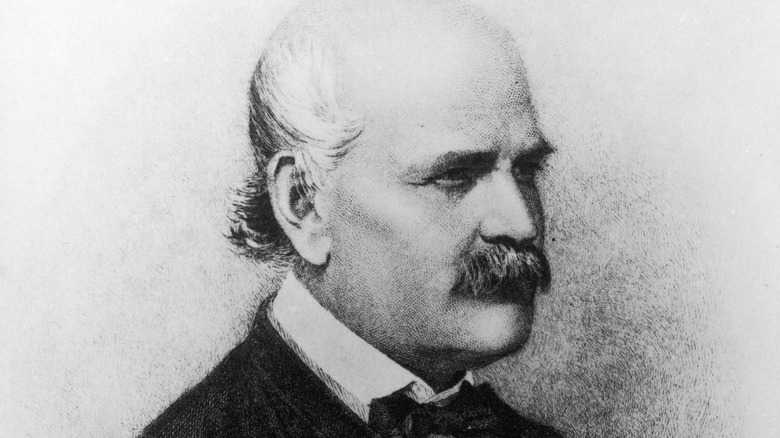

Ignaz Semmelweis saved untold people by washing his hands

At first, Ignaz Semmelweis may have seemed like any other newly minted doctor in 1844 when he received his degree in Vienna. But after starting work at an obstetric clinic, he became all too familiar with puerperal fever, in which postpartum women fell victim to sometimes deadly infections. Those who delivered in a hospital faced the worst odds, with some encountering chilling mortality rates of 30%. Even worse, many doctors just sort of shrugged their shoulders and accepted that women were just going to keep dying.

Semmelweis decided to actually do something. At first, he considered whether differences in birthing positions or even a priest scaring patients were to blame, but found no supporting evidence. When an associate autopsying a patient who had died of puerperal fever wounded himself mid-procedure, he died of a very similar infection, and Semmelweis concluded that the two deaths were caused by the same pathogen. When he ordered medical students to begin disinfecting their hands with a chlorinated solution before examining patients, death rates plummeted from 18.27% in one ward to just 1.27%.

Unfortunately, the tragic part of Semmelweis' story is that the abrasive doctor experienced major opposition. Ultimately, he began to experience mood disturbances and other mental health issues, to the point where he was committed to an asylum in 1865, at just 47 years old. He died just two weeks later, ironically due to an infected wound.

Mary Anning should be a bigger figure in paleontology

While the crazy story of the bone wars deserves attention, there's another very real figure in the field of paleontology who doesn't get nearly enough recognition. Upon first glance, Mary Anning may have seemed like any other woman living in the seaside town of Lyme Regis on the southwestern coast of England, but she was also a fossil hunter. Fossils sometimes emerged from the crumbling cliffs near her town, leading some to risk injury and death amongst rockslides to scoop up interesting specimens and sell them to collectors. Mary's father Richard did just that, using both the area's rich fossil deposits, its tourist hub, and growing interest in the natural sciences to make money for his family.

When he died in late 1810, Mary and her brother Joseph continued fossil hunting, and the two found an ichthyosaur over the course of 1811 and 1812. On her own, Mary found a nearly complete plesiosaur fossil in 1823. While scientists at the prestigious Geological Society of London debated its authenticity, Anning wasn't invited. Likewise, she was rarely credited by collectors or museums.

Eventually, tourists began making special trips to see Anning and her fossil shop. She gained some recognition for her carefully observed finds of pterosaur fossils, coprolites, and small marine creatures, though she struggled financially all her life. When she died of breast cancer in 1847, she was still short of money and recognition.

Clair Patterson upended the gas industry

Prior to 1921, cars often experienced engine trouble known as "knocking," but engineer Thomas Midgley Jr. had a solution: lead. Specifically, he proposed adding tetraethyl lead (TEL) to gasoline to increase engine efficiency and do away with that terrible knocking noise. Actually, ethanol seemed the best option, but Midgley's employer, General Motors, didn't like that it couldn't patent ethanol. TEL seemed to be a fine replacement that allowed GM to control production. Who cared if it was a known toxin and spewed lead out of a car's exhaust?

Clair Patterson did. While a geochemist at Caltech, he published a 1965 paper revealing high levels of lead in the environment due to human activity. The average American at the time was so chock-full of the stuff that they were dancing on the edge of toxicity, he said. Patterson originally wanted to uncover the precise age of the Earth, which required measuring uranium and lead isotopes. But, despite highly controlled lab conditions, Patterson found lead all over the place. He even examined ancient human remains and compared lead levels there to modern samples, confirming that modern humans had far higher lead exposure.

Patterson realized that TEL deposited via engine exhaust (as well as other sources like industrial production) was almost everywhere. Patterson controversially testified before the U.S. Senate in 1970, where his research provided backing for the passage of the Clean Air Act of 1970.

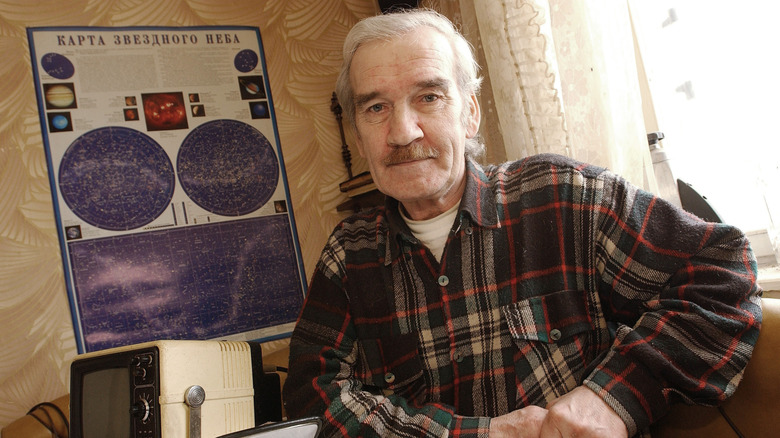

You have Stanislav Petrov and Vasily Arkhipov to thank for not living in a nuclear wasteland

If everyone really understood just how close we got to WWIII not once but twice (at least), you might never sleep. Consider the dual cases of Vasily Arkhipov and Stanislav Petrov. Arkhipov was an officer on a Soviet submarine in October 1962 in the midst of the Cuban Missile Crisis. When they encountered a U.S. destroyer, the surface ship began dropping depth charges to get the Soviets to surface.

Only, the submariners couldn't reach Moscow and thought it was perhaps the outbreak of war. Should it fire a nuclear torpedo? Two of the three senior officers aboard agreed to do so, but Arkhipov, the second captain, refused. Without his approval, the torpedo had to stay in its tube. Instead, he convinced them to surface, where they found war had not broken out.

Two decades later, on September 26, 1983, Stanislav Petrov was a lieutenant colonel on watch in a sleepy military outpost. In the middle of the night, Petrov was shocked to see the early warning system blare to life, warning of five intercontinental ballistic missiles seemingly launched by the U.S. military against the U.S.S.R. If Petrov reported it to command, they would retaliate with no time to reach out to the Americans. Instead, Petrov rightfully clocked it as a false alarm and did nothing. Good thing, too, as the combined death toll of U.S. and Soviet strikes would have soared into the hundreds of millions, with many more likely dying in the lingering aftermath.

Ida B. Wells was a major civil rights figure

Ida B. Wells, born in 1862 in Mississippi, started her life as an enslaved person and was freed while still a young child. Her parents, Elizabeth and James Wells, were especially focused on education and community work, with her father joining the Freedman's Aid Society and helping found Rust College, a historically Black institution still operating in Holly Springs, Mississippi. Ida herself attended Rust College, though she was struck by terrifically bad circumstances when she had to drop out and her parents died of yellow fever when she was only 16.

Later, after having worked as a teacher and taking care of her remaining family, she enrolled at Nashville's Fisk University. It was while traveling back to Nashville in 1884 that she had a dramatic encounter with racism. Though she'd bought a first-class ticket, train personnel attempted to force Wells into a segregated car. She fought back and was kicked off the train. She sued and won a settlement, but the Tennessee Supreme Court overturned the case.

Wells began publishing articles discussing race and segregation, and even came to own two newspapers while still working as a teacher in Memphis. When her work — initially published under a pseudonym — came to light, she was fired from her teaching job in 1891. The next year, she began more directly criticizing lynching murders of Black Americans and started working as an investigative journalist. On one occasion, an angry mob entered her newspaper's offices and trashed the place. Wells, who was in New York at the time, permanently moved away from the American South.

Andreas Vesalius upended centuries of bad anatomy

If you view doctor's appointments as a nuisance at best, consider how much worse it would be if we still thought human anatomy was pretty much the same as a sheep's. That was the sort of mistake made by ancient Greek physician Galen and perpetrated by his many adherents for centuries afterward. It's not precisely his fault, as Galen was doing his best in a society that condemned human dissection. His next best thing, in at least one case, was to crack open a sheep's head and assume that its internal structures were more or less the same as ours.

So, how did we get from Galen's whoopsies to our more advanced anatomical knowledge? Andreas Vesalius, who as a doctor in Renaissance Europe was able to dissect human remains and was willing to entertain an almost heretical notion: what if Galen was wrong? Other doctors were aghast, but Vesalius was willing to rely on his own findings instead of longstanding convention.

By 1543, his richly illustrated anatomy textbook, "De humani corporis fabrica libri septem" (you can just call it the "Fabrica"), was published. It was nothing short of revolutionary, with artistic and scientific achievements that included paper flaps allowing readers to examine the different aspects of human anatomy in sequence. Eventually, Vesalius served as physician to Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, to whom he dedicated and presented a copy of the "Fabrica." Vesalius also produced a follow-up anatomical text known as the "Epitome."

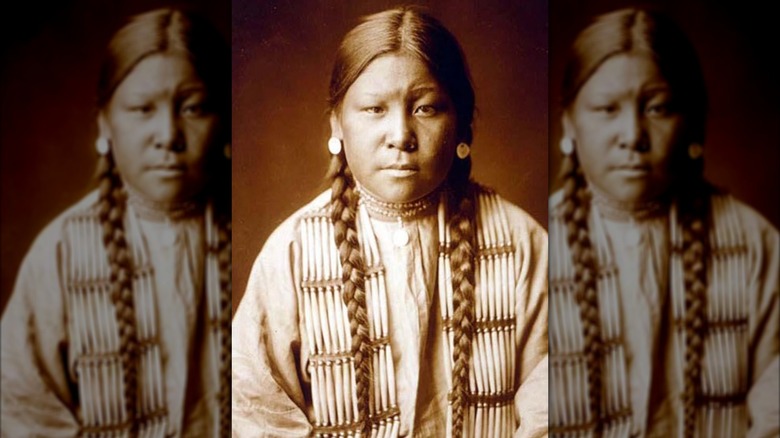

Buffalo Calf Road Woman faced off against Custer

The 1876 Battle of Little Bighorn saw a group of Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne combatants facing off against U.S. Army troops led by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer. This engagement infamously ended with the complete devastation of Custer's 600-man force. But, while the 19th-century U.S. Army didn't admit women, the Lakota and Cheyenne people did have a small number of women who engaged in this fateful battle. Perhaps most striking of all are the accounts swirling around Buffalo Calf Road Woman (sometimes also called Buffalo Calf Trail Woman). Another woman's eyewitness account published in 1967's "Custer on the Little Bighorn" said that Buffalo Calf Road Woman (here referred to as Calf Trail Woman) "was the only woman there who had a gun [...] She was the only woman I know of who went with the warriors to that fight."

Accounts from the Northern Cheyenne go even further and say that Buffalo Calf Road Woman may have dealt a major blow against Custer himself by knocking him off his horse. She may have been amongst the group of women who moved through the battlefield and finished off lingering soldiers — Custer included. Afterward, Buffalo Calf Road Woman and her husband, Black Coyote, moved to an Oklahoma reservation in 1877. They attempted to return home, but Black Coyote reportedly became mentally ill and violent. When he killed U.S. soldiers, he was executed, while Buffalo Calf Road Woman grew ill and died in May 1879.

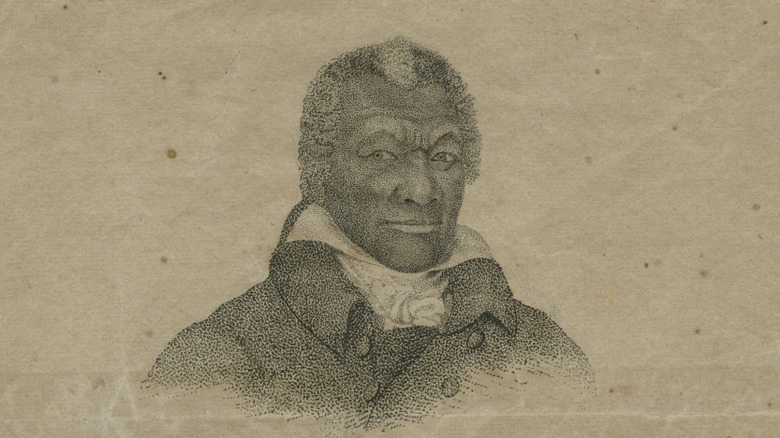

Revolutionary War histories often forget James Armistead Lafayette

Around 1760, James Armistead was born enslaved in Virginia. With the arrival of the revolution, he enlisted in a colonial unit associated with the Marquis de Lafayette, then further distinguished himself by becoming a spy. It was certainly a complex situation, as although up to 8,000 Black men fought for the Continental Army, an estimated 20,000 allied themselves with the more overtly anti-slavery British.

Armistead's personal motivations are all but impossible to tease out, but we know he gained unprecedented access to British sources, ferried vital intelligence back to the Continental Army, gave the British bad information, and even worked for the infamous Benedict Arnold. In 1781, Armistead informed Lafayette and George Washington that British reinforcements were on their way to the Battle of Yorktown. They managed to block these new troops, leading to a decisive colonial victory.

Lafayette thought highly of Armistead's work, writing in 1784 that he "appears to me entitled to every reward his situation can admit of" (via Mount Vernon). Yet Armistead was forced to return to being enslaved, as his secret intelligence work disqualified him from the emancipation granted to other soldiers. It wasn't until Lafayette stepped in once more that Armistead was granted freedom in 1787, and the French military officer was so instrumental in Armistead's life that he added Lafayette's name to his own as a mark of esteem.

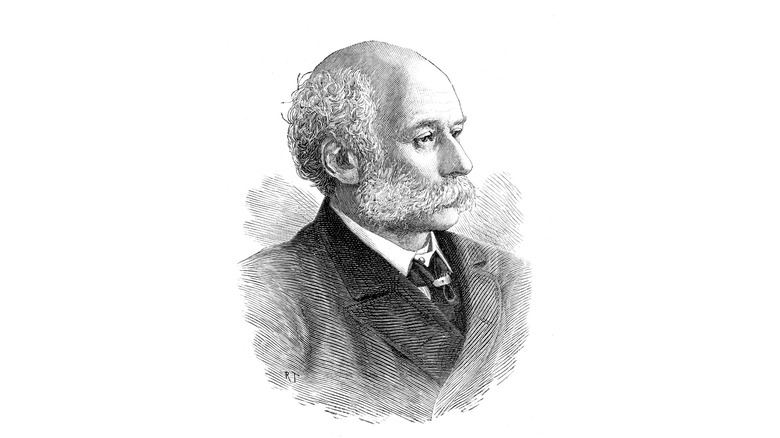

Joseph Bazalgette, sewer king

Consider this: would you rather live in a London of cesspits and open drainage channels full of all manner of waste, or one with covered sewers? We thought so, too, but who's to thank for such a momentous change? Well, Joseph Bazalgette might not have innovated enclosed sewers, but his extensive redesign of London's sewer system in the middle of the 19th century almost certainly saved thousands or even millions of lives. You see, by the 1850s, many Londoners were struck by cholera epidemics, a deadly disease that festered and grew in unsanitary conditions. What's more, London was decidedly gross.

In the summer of 1858, hot weather essentially cooked all that open water, creating a stench so stomach-turning that it became known as the Great Stink. This was apparently the last straw for city organizers, who got to work fixing the notoriously bad sewer system. In 1852, Bazalgette was elected as the Metropolitan Board of Works' engineer. With the odiferous summer of 1858 in the immediate rear view, he got to work essentially redesigning London's sewer system, which included about 1,300 miles of pre-existing sewer lines and a woefully unaddressed drainage system.

Bazalgette's redesign rerouted sewage away from populations and to treatment plants. By the 1870s, embankments he'd had built along the Thames also reclaimed over 50 acres of tidal flats, protecting portions of the new sewer, providing new land for development, and making way for sections of the all-important Underground rail system.

Henrietta Lacks fundamentally changed medicine

Remarkably, many vaccines, medications, and other treatments that relied on human cell cultures to get their start all come back to the controversial story of a woman named Henrietta Lacks. Lacks was a housewife and mother of five who lived near Baltimore, Maryland. In early 1951, she went to The Johns Hopkins Hospital — one of the few that treated low-income Black people in the area — to investigate the cause of odd bleeding she'd noticed. Doctors found a large, malignant tumor on her cervix and took a cell sample, sending it to a Johns Hopkins lab without her knowledge. Despite undergoing an early form of radiation treatment, Lacks died from the progression of her cancer by October, at only 31 years old.

However, her cell line, sent to the lab of Dr. George Gey, lived on — and on. Unlike previous cell lines, Lacks' cancer cells were incredibly resilient. Deemed HeLa cells, they were shared with many other labs and proved instrumental in scientific and medical research. HeLa cells played a role in the development of the polio vaccine, treatments for sickle cell anemia, HIV medications, and vaccines for HPV — the last of which can lead to some forms of cervical cancer. Yet Lacks didn't get greater recognition for her contribution until the early 2000s, when author Rebecca Skloot's original research brought the story of Lacks, her family, and the uncomfortable meeting of medical science and racism to greater attention.

Marian Rejewski deserves more credit for breaking the Enigma code

For a good chunk of WWII, German forces used the Enigma machine, which scrambled messages into an incomprehensible mess to anyone without a cipher. When you read about the Enigma code, you'll soon see mention of the British team at Bletchley Park, where mathematician Alan Turing played a key role in cracking the code. But Turing and his team weren't the first to figure out the Enigma. That honor instead goes to a Polish team headed by mathematician Marian Rejewski.

Poland had been attempting to break into German Enigma communications since the 1920s, using mathematical models instead of more common (and less successful) linguistic ones. Captain Maksymilian Ciężki of the nation's Cypher Bureau recruited a highly intelligent former student, Marian Rejewski, along with two other former students, Jerzy Różycki and Henryk Zygalski. When this team got hold of an Enigma manual and a couple months' worth of German Enigma settings, Rejewski finally figured out how the machine worked.

Their success was dulled somewhat when, in October 1936, the German military began changing the code every day instead of every three months and later increased the complexity of the machine. Even so, Rejewski and his team got past those moves and managed to decrypt the vast majority of Nazi plans before the Germans invaded Poland in September 1939. At this point, their work was passed on to teams in the safer territories of France and Britain.

If you need penicillin, thank Margaret Hutchinson Rousseau

Penicillin's use as an antibiotic was first identified when British bacteriologist Alexander Fleming came back from a 1928 vacation and found that pathogens in one petri dish left in his lab were killed off by a strain of Penicillium mold. However, it wasn't until the 1940s that it was developed as a powerful antibiotic.

With so many medical applications and the threat of war rearing its gruesome head, it became clear that someone had to learn how to make a bunch of penicillin, and fast. Scientists, pharmaceutical companies, and the U.S. government improved on lab techniques, developing a tank-based submersion method that produced higher yields. Amongst this diverse group was a chemical engineer named Margaret Hutchinson Rousseau who worked for Pfizer in the 1940s. There, she brought together her industrial design experience with the penicillin problem to create a deep-tank fermentation process that allowed for commercial-level production of penicillin. By June 1945, more than 646 billion units of penicillin were produced every year, thanks in part to Rousseau's innovation. Rousseau is also credited as the first American woman to earn a chemical engineering doctorate, as well as designing production processes for synthetic rubber, another key wartime material.

Herman Haupt was key to the Union's Civil War victory

If there's only one lesson you learn from the long, agonizing history of war, it may as well be this: you'd better be in control of your supply lines. When it came time for the Union to think about all this during the American Civil War, Herman Haupt came to the rescue. Haupt came from humble origins, rising to graduate from West Point in 1835, but he quickly resigned his post-graduation army commission to become a railroad engineer. He was soon devising mathematical models for testing bridge strengths, as well as coming up with high-level engineering ideas and custom-built equipment. Economic woes made things dire for Haupt and his family, but the 1860s saw him invited to Washington, D.C., to oversee the construction of railroads for a Union already embroiled in war.

That was especially tricky because the U.S. did not have an especially well-connected rail network and was beset by quarreling rail companies, necessitating the construction and defense of new lines. Eventually given the rank of brigadier general, he also sometimes came into conflict with other officers, who rankled at letting Haupt do his thing, even if it was the vital work of transporting supplies and troops. He eventually resigned in 1863, again apparently uncomfortable with the limitations of military bureaucracy, but those who trained under him were able to keep the railroads running through the end of the fighting.

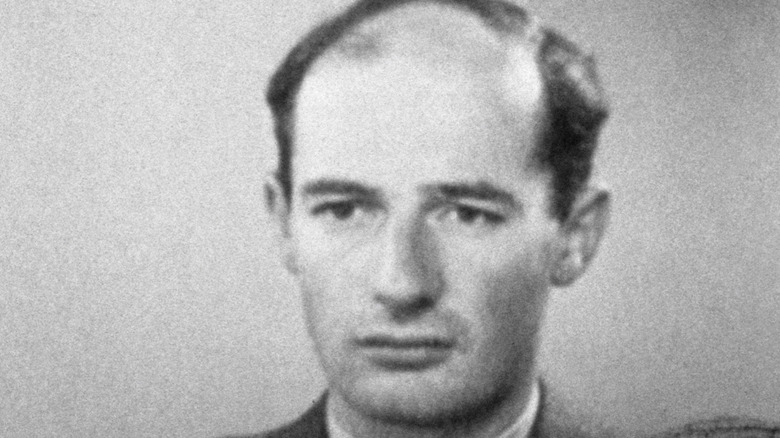

Raoul Wallenberg rescued thousands of Jewish people

In 1944, the Swedish businessman Raoul Wallenberg, upon seeing the Nazi persecution of Hungarian Jewish people, managed to secure a diplomatic post in Budapest with the intent to save people. There, he was able to help thousands of Jewish people shelter in homes under the protection of neutral countries, with estimates ranging from a low of about 4,000 to as many as 35,000 people saved. Wallenberg also interrupted deportations to concentration camps and handed out supplies like food and clothes. He used his diplomatic status and bureaucratic ties to get people safe passage out of danger, sometimes forging necessary papers.

While he was hardly the only person in Hungary and beyond doing this sort of work, Wallenberg's story remains haunting because we still don't know exactly what happened to him. He was in Budapest when the Soviets finally took over the city in early 1945. At this point, Red Army officials appear to have grown suspicious and marked him out as a possible spy, arresting him on charges of espionage in January. Or, as some accounts suggest, he was under "military escort" and not technically arrested.

Either way, patchy postwar records indicate that he was held in a prison until 1947, where he reportedly died in his cell of a heart attack. Even if you remain suspicious, as far as much of the world was concerned, Wallenberg had disappeared in the chaotic aftermath of the war. It wasn't until 2016 that Sweden officially declared him dead.

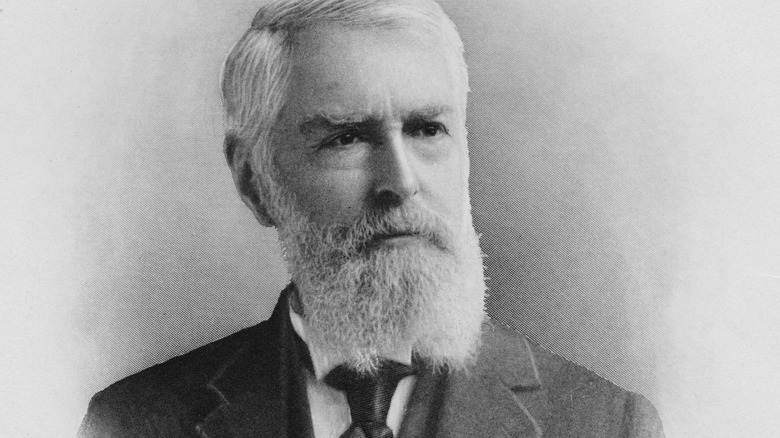

William Wilberforce was a major abolitionist

From a U.S. perspective, the end of enslavement is inextricably tied up with the American Civil War. But in Britain, it had already been debated, with 18th-century politician William Wilberforce emerging as one of the most vocal anti-enslavement campaigners. Things didn't exactly start that way, as Wilberforce was apparently a nice enough — if sort of aimless — young man while attending Cambridge.

Elected to the House of Commons in 1780, he became increasingly outspoken about political reform; after converting to evangelical Christianity, he became a staunch abolitionist who co-founded the Anti-Slavery Society and routinely, vociferously sponsored anti-slavery bills in Parliament. His first few attempts gained attention for his speeches but never managed to pass into law.

Still, Wilberforce and his abolitionist associates in Parliament and beyond were gaining traction. By 1792, he had managed to secure a sort of compromise in which enslavement would eventually be abolished in the British Empire, though even that seemed to stall until 1807, when a bill to ban enslavement in the British West Indies actually passed and the enslavement trade was technically over with. That didn't free anyone already enslaved, however, and so Wilberforce and company kept at it. In fact, he was still working at it when he finally retired from politics in 1825. At least he managed to live just long enough to see the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act pass and free enslaved people in nearly all British territories, and make Canada a free territory in the sights of enslaved people fleeing the United States.