The Messed Up Truth Of The Texas Revolution

In the rankings of iconic American moments, it's hard to think of one more iconic or more American than the Battle of the Alamo. The bloody siege endured by Texan revolutionaries at the hands of Mexican dictator Santa Anna is so intertwined with the legend of America's rise that it's hard not to picture Davy Crockett fighting while draped in the Stars and Stripes and yelling, "'Murica!" We're all familiar with the basic outlines of the story: Texas got fed up being in Mexico, Mexico tried to stop it leaving by killing everyone at the Alamo, so Texas righteously pummelled the Mexican army, then had a victory party by joining the USA. Man, just reading that sentence is enough to bring you out in a severe case of patriotism.

The trouble is, that spirit-stirring summary is just that — a summary. And it's one that misses all the really dark and disturbing stuff that happened in the course of Texas's 1835-36 revolution. Stuff so unsettling it might make you see Texas' foundational myth in a whole new light, one that's less "remember the Alamo!" and more "what the heck, Texas?" From fights over grass to that peculiar institution, here's the messed up truth of the Texas Revolution.

The Texas revolutionaries were invited in by Mexico

What do vampires and Texan revolutionaries have in common? Answer: Whatever happens, you should never, ever invite them into your home. In the early 1820s, Mexico had just finished its own bruising revolution against Spanish rule (pictured above). Unfortunately, the heavy fighting had decimated the population, especially on the northern frontier, leaving a whole load of open spaces which were nominally Mexico but actually just kinda there for the taking should another nation decide to gobble them up (cough, USA, cough).

So Mexico needed to get those regions filled with loyal Mexican subjects fast. Only there weren't enough actual Mexicans left, and those that were still around were all like, "Move to that place? Uh, no thanks." Their solution? Get non-Mexicans to do the repopulating.

According to the official website of the Alamo, beginning in 1820, American and European settlers were encouraged into northern Mexico with promises of free land, seven years of tax breaks, and — sigh — the legal right to keep owning slaves. With incentives like that, who could say no? By 1823, 500 white settlers had arrived in what we'd now call Texas but back then was part of Coahuila y Tejas. Unfortunately for Mexico, these settlers were the same people about to revolt against their nation. Man, talk about ungrateful guests.

The settlers replaced the Mexicans

We've all seen places where gentrification has pushed the locals out, and that's basically what happened in northern Mexico after 1823. Only instead of tech gurus and failed screenplay writers, it was an influx of cowboy hat-wearing farmers that turned Coahuila y Tejas from a Mexican state to an overwhelmingly white one.

Here are some figures, according to Smithsonian. By 1830, white settlers in Texas outnumbered Mexicans five to one. This was partly due to Mexico's generous immigration policy, but it was also due to poor border screening. The people in charge of monitoring the influx were often white settlers themselves, like Stephen F. Austin (pictured above). Many of these guys tended to look the other way even if the new arrivals were con men on the run from the law (stand up, Jim Bowie). They also weren't great at checking if the newbies were loyal to Mexico. In fact, a whole bunch of Texians — as they called themselves — moved in while openly proclaiming that they wanted Texas to secede.

Eventually, the Mexican government cottoned on to the fact that it had shot itself clean through the foot and cancelled the settlement program. By then, though, they had tens of thousands of seditious white guys living on their northern frontier. All it would take would be the slightest spark to turn this smoldering issue into an inferno.

Everyone was using one another as political cover

When Mexico banned both further immigration and slavery in Texas in 1830, the Texans were super not happy. But they couldn't just up and revolt while Mexico was still united. What they needed was a cover story, like the one that conveniently arrived in 1832. That January, a hothead soldier named Antonio López de Santa Anna (pictured in battle) started a barracks revolt down in Veracruz over the government disrespecting states' rights. While this would eventually come to seem incredibly ironic, it also provided some handy cover for the unhappy Texans.

On June 13, 1832, a group of settlers annoyed at the Mexican government held a secret meeting at Turtle Bayou. There, they decided the best way forward was to do their own thing, while outwardly claiming they were really supporting Santa Anna's federalist revolt (via Medium). And just like that, the Texans were suddenly no longer ungrateful settlers destabilizing Mexico but Mexican citizens taking a political stand. But it wasn't just the Texans using the situation as cover. Santa Anna was only too happy to welcome another department into his revolt, and he sent a general north to lavish praise upon Texas. The upshot? Santa Anna won his revolt and eventually became president. This wouldn't work out well for anyone.

The Seven Laws were like the Seven Screw Yous

When Santa Anna became president of Mexico, people in Texas were all like "party time!" As the biggest respecter of states' rights in Mexico, Santa Anna was the guy the settlers had been dreaming of — someone who'd leave them alone to run Texas like an independent state. But Santa Anna was a political weasel who'd take any position so long as its end goal was helping Santa Anna. After he secured the presidency, he dropped his federalism faster than a flaming pair of pants, and instead, he laid down his Seven Laws.

Coming in late 1835, the Seven Laws were so hilariously anti-federalist they must've seemed like a practical joke. Basically, if you boiled the laws down, they would read something like this: "Laws One through Seven — Santa Anna rules, everyone else drools." States' rights were crushed, and every department was placed under military command. Those nightmares about the guv'ment that keep your paranoid uncle awake at night? Santa Anna was basically making all of them come true at once.

To say this was a screw you to the population of Mexico is a little like noting the religious propensities of Popes or the defecation habits of mammals from the genus Ursidae. The states of Zacatecas and Coahuila y Tejas exploded in revolt. Spoiler alert: Only one of those revolutions is actually gonna pan out.

The other revolution didn't pan out so well

When the people began rising up against Santa Anna's Seven Laws, the Mexican dictator basically had a choice: back down or crack down. Being a dictator, Santa Anna chose the latter option. But while his attempt to crush Texas' revolution wouldn't pan out so well for him, his crushing of the Zacatecas revolution was like a textbook case study in being an authoritarian monster.

Because Zacatecas was closer than Texas, Santa Anna chose to go down there and put things in order first. And by "put things in order," we actually mean "raise so much hell that it devastated the state for decades to come." As the Houston Institute for Culture describes, Santa Anna did to Zacatecas what pure unfiltered ethanol does to your liver. He destroyed it. The dictator allowed his men to ransack the capital city, attack the state's silver mines, and make off with all the silver. He then issued a decree separating resource-rich Aguascalientes from Zacatecas, just to make it that much harder for the rebellious state to economically recover. Geez, talk about an overreaction.

The Grass Fight was an embarrassing, messed up fiasco

With Zacatecas now standing as a flaming monument to what happens when you cross Santa Anna, the revolutionaries in Texas decided to get serious about their revolt. Things technically kicked off with the Battle of Gonzales on October 2, 1835, but that was such a half-hearted effort that calling it a battle is really overstating it. Mexican casualties were minimal, and the only Texan injury was a guy who fell off his horse and bloodied his nose (via Medium). Nah, the action only really started when a Texan militia laid siege to San Antonio. Unfortunately, even this serious attempt at playing soldiers would wind up leaving everyone embarrassed, courtesy of the Grass Fight.

According to ThoughtCo, during the siege, the Texans spotted a relief column of Mexicans approaching the town with pack animals laden down by heavy bags. Determined not to let the besieged Mexicans get any supplies, Jim Bowie and around 150 men rode out to make mincemeat of the relief column. As the Texas State Library describes, the Texans attacked the Mexicans, killing three of them and seizing their animals. It's at this point that things got really dumb.

Opening the animals' heavy bags, the Texans discovered not supplies or coins but piles and piles of grass. The "relief column" they'd attacked had been a bunch of local guys just trying to get some food for the animals trapped in San Antonio. Awkward.

The Texan siege of San Antonio was brutal

When you hear the words "siege" and "Texas Revolution," you probably think of the siege of the Alamo. But that wasn't the only siege in town. In late 1835, the Texans surrounded the department capital of San Antonio. Although things started off awkwardly (see the Grass Fight for proof), they soon descended into something far more brutal. On December 5, the Texans decided to attack the town. By the time they finished, the streets would be slick with blood.

According to ThoughtCo, the attack began when Texans shelled the city, taking the holed-up Mexicans by surprise. It then turned into an all-out assault, with hand-to-hand combat leaving bodies outside houses all along the streets. To get an idea of just how bloody things got, consider this. On December 4, Mexican forces had greatly outnumbered Texans. By December 9, that had reversed. The Texas State Historical Association claims over 150 Mexicans lost their lives in the assault, compared to around 30 or 35 Texans.

The surviving Mexicans were forced to retreat inside the Alamo, where the Texans laid siege to them again. Finally, the Mexican general surrendered, and he and his men were allowed to leave after disarming. This is the bit everyone remembers today, the "bloodless" capture of the Alamo from Mexico. They just forget all the super bloody stuff that came immediately before.

Santa Anna's men were forced to fight

The Battle of the Alamo is famous for its heroism, as around 200 Texans valiantly held off over 1,000 Mexican soldiers for 13 days. But the image you might have of these rag-tag frontier men staring down a well-trained army isn't exactly accurate. See, when Santa Anna (pictured above) marched north to mess up Texas, it wasn't at the head of a gung-ho invasion force. It was at the head of hundreds of ill-equipped indigenous peasants dragooned into fighting.

According to Smithsonian, Santa Anna's army was run on conscription, and conscription in 1830s Mexico meant being told at gunpoint to leave your village and come fight. Many, if not most, of his men were indigenous peasants corralled during the long march north, and plenty of them were ill-equipped. Winter that year was viciously cold, and there are tales of men forced to wrap their bare feet in rags to stave off frostbite. Many died on the journey.

If you've ever seen the casualty statistics from the Alamo and given a little inner cheer at the much higher number of Mexican deaths, just know that most of those killed were starving, frostbitten peasants forced to choose between marching toward a fortified compound and likely death or refusing to go and facing certain death at Santa Anna's hands. Err ... 'Murica?

The Battle of the Alamo was messed up, gory, and pointless

Far from being a simple battle fought with simple guns, the Battle of the Alamo was like the climax of The Wild Bunch on steroids. As Smithsonian describes, the Texans shoved random chunks of metal into their cannons and then blasted them into the advancing army, causing exactly the sort of gory injuries you'd normally associate with super disturbing horror movies. On the other side, the battle's endgame came down to hand-to-hand combat, often meaning Mexican soldiers butchering Texans with bayonets. Smithsonian quotes historians estimating that, all in all, between 189 and 249 Texans and 145 to 395 Mexicans (including 250 who later died of their wounds) were killed at the Alamo. It was a bloody day.

Know what else it was? Completely pointless. As Texas Monthly explains, the Alamo wasn't just carnage on a vast scale. It was also a colossal waste of time. Despite being on a main road, the Alamo actually held little strategic value, something Sam Houston had recognized after San Antonio fell into Texan hands. He'd even ordered the useless compound destroyed, only for Jim Bowie to go off-script and instead garrison it. But if it was so useless, why did Santa Anna insist on attacking? Some think he was just annoyed about the Texans taking it from the Mexicans and wanted to take it back to prove a point. If that's the case, then hundreds died proving that point.

The massacres didn't stop at the Alamo

The Alamo's endgame was a series of massacres. Inside, the Texans were chopped up with bayonets, while outside, Historian Alan Huffines contends some 50 men who tried to flee were run down and gored with lances (via Smithsonian). After it was all over, Santa Anna had all the free male survivors executed (women and slaves he allowed to leave). But if that sounds seriously messed up, just know it wasn't even Santa Anna's worst massacre of the revolution. That would come at Goliad.

The next major Texan battle after the Alamo, Goliad isn't well-remembered today because it was less a heroic last stand and more an epic blunder. After a series of incompetent decisions (via History), some 350 Texans managed to get themselves captured. The Mexican commander assured the prisoners they would be treated as POWs, and he even wrote to Santa Anna asking him to show leniency. Instead, Santa Anna wrote back demanding all 350 men be executed.

On March 27, the prisoners were put into four columns and marched off in different directions. They went peacefully, having been told they were being transferred to prison. But the minute they were out of sight of the other columns, the guards opened fire, slaughtering the prisoners. Some 350 died that day. But the last laugh was on Santa Anna. It would be the Goliad massacre that spurred the Texans on to their final victory at the Battle of San Jacinto.

Slavery was reinstated after the Texas Revolution

Ah, slavery. The thing Southerners used to call their "peculiar institution," and we now call "that really friggin' awful thing we all feel super guilty about." Well, prepare to feel even more guilty, nostalgists for the Texan Republic! After the Battle of San Jacinto ended the revolution, Texas declared itself a sovereign state. One of the very first laws the new republic passed was reinstating slavery (via Texas State Historical Association).

It's worth quoting section 9 of the republic's constitution: "All persons of color who were slaves for life previous to their emigration to Texas, and who are now held in bondage, shall remain in the like state of servitude." Pretty unambiguous, no? But the Texan constitution actually went even further than just allowing slavery to continue. Among its other clauses, section 9 stated that "nor shall congress have the power to emancipate slaves," and it also specifically made it illegal for owners to emancipate their own slaves. Just think about that. These guys cherished the idea of slavery so much that they made it illegal for other slavers to change their minds.

Mexico had banned slavery in general as far back as 1829, and closed loopholes for Texas in 1830. Had Santa Anna won his war, the estimated 5,000 slaves living in Texas would've gone free. Instead, they remained in chains until 1865 — another 30 years.

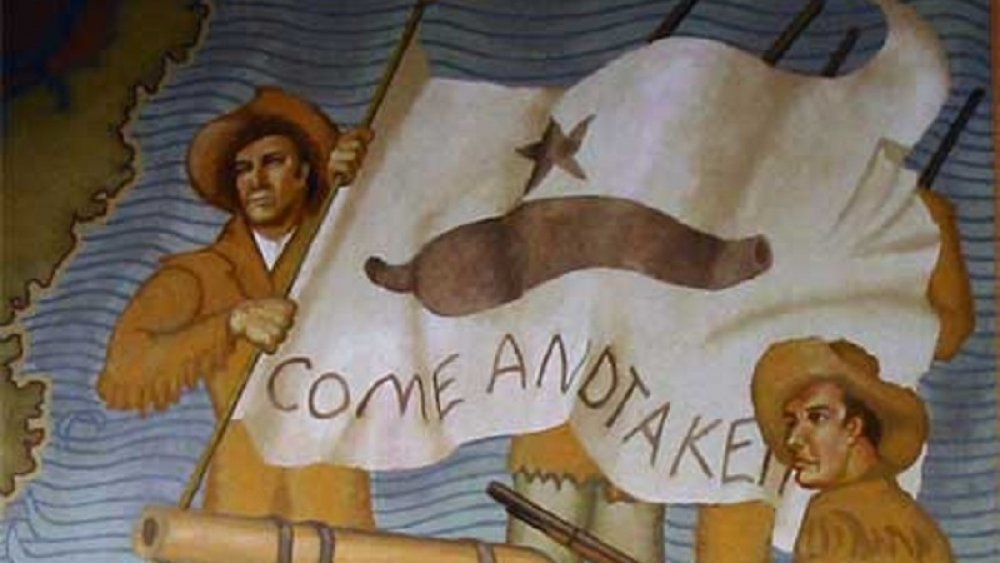

The great whitewashing of the Texas Revolution

Despite what historical movies would have you believe, the Battle of the Alamo was not a bunch of white guys facing down hordes of swarthy Mexicans. While white Texans made up the majority of the revolutionaries, they were joined by Mexican-descended Tejanos, southern Europeans, Native Americans, free blacks, and even slaves who fought alongside them. In fact, the only reason we know what happened at the Alamo is because a slave named Joe was spared and later reported it. The Texas Revolution was so multi-ethnic that Smithsonian has called it "almost a laboratory in multiculturalism."

Yet barely had the smoke settled over the Alamo than the story of all the non-white fighters was being written out of history. Paintings, textbooks, and (later) movies all conspired to enforce the myth that the revolution was a race war. It was whitewashing on a colossal scale. And the end result was a sad, enduring belief in the Texas Republic as some kind of white's only paradise, all courtesy of those lies taught in history class.

Smithsonian's article interviewed Latinx Texans who grew up in the mid-20th century and recalled being bullied during history lessons on the Alamo (sometimes by their white teachers). At the same time, the fact that many of the heroes of the revolution were slaveholders was carefully deleted, creating a myth not just of heroic white dudes but heroic white dudes who didn't own other people and treat them as disposable possessions. History, kids — it's sometimes really messed up.