The Most Deadly Outbreaks In History

Of all the ways humanity could abruptly end at a moment's notice, from giant meteors to nuclear winter, disease is one of the scariest. It's invisible, it can spread quickly, and the only surefire defense is complete isolation, a terrifying prospect for the majority of humans.

In movies or TV, disease is a slow and painful death, and in the lead-up to its spread, you can see society's structures crumbling down and failing when there aren't enough people to keep order any longer, like in The Walking Dead or Stephen King's The Stand. And even the world's smartest scientists are helpless against it, like in the films Contagion or World War Z. But real life is a different story, so you need to look to the past in order to understand how humanity responded to deadly outbreaks.

While in early 2020, fears are riding high about the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, it's got a long way to go to stack up to the various plagues throughout history.

The Black Death still echoes today

When you think of deadly pandemics in history, one looms larger than the others, despite it being many centuries ago, due to its massive spread and staggering number of deaths. The Black Plague, also known as the Black Death, is America's cultural go-to for the spread of disease, even nearly 700 years after it happened. European history is forever marked by the bubonic plague, and it's likely you heard about it in school at a very young age.

Arriving in around 1347, the Black Death spread all across Europe in less than a decade. It's estimated to have killed 20 million people, almost a third of Europe's population, and it took further decades for the population to return to its previous numbers. Marked by black sores filled with pus and blood, the Black Plague was known for working very quickly, often killing in just a few days, according to History.

Since the spread of illness was not yet understood, scientists and doctors of the time weren't even sure how one could catch it, other than by being in proximity to someone who was sick. One report from the time alleged that looking into a sick person's eyes as they died would guarantee you got sick as well. So many people died that the survivors had to come up with ways to remove the dead. Massive pits of bodies became common, as well as daily pickups of corpses from households throughout the land.

The Plague of Justinian devastated the Byzantine Empire

In 541 CE, the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I was about halfway through his reign, but the thing that would be most identified with his name was just beginning. Fleas carried the mysterious illness throughout the empire, sickening millions and killing what is now estimated to have been approximately 10 percent of the world's population.

Although we only have limited primary sources to look back on (many older plagues still have unknown causes scientists can only guess at), the Plague of Justinian, so named because of the Emperor and also because of his poor handling of it, seems very likely to have been the exact same bubonic plague that led to the Black Death, like a bad prequel to a blockbuster film. The exact symptoms of the Plague of Justinian aren't known, but what is known about it has left researchers convinced it was the same disease.

When workers and farmers fell ill and couldn't finish Justinian's numerous projects, he actually raised taxes on survivors to try to recoup some of the costs, leading to him being widely hated among his own constituents, according to Passport Health. He even tried to make the living pay the taxes of their dead neighbors, which is just next-level greed. As the pandemic ended, Justinian's empire began crumbling as well, and a horrible plague that bore his name is its most lasting remnant.

The Cocoliztli Epidemics decimated indigenous Mexicans

In the early 1500s, Spanish explorers were just reaching the lands that would one day become Mexico. The native Aztec people, naturally, weren't terribly happy to see them, and also weren't very fond of the Spanish trying to claim their land for themselves. But while out-and-out war was just beginning, the Aztecs were dealing with something just as deadly as the conquistadors showing up on their shores.

A disease, which the Aztec called cocoliztli (meaning pestilence in the Nahuatl language) was sweeping the empire. Symptoms included severe jaundice, bleeding from the ears and nose, and vivid hallucinations, according to Science magazine. Convulsions and death followed soon after. The illness worked fast, and could kill in just days. Before long, it had killed about 45 percent of the Aztec population.

Already exhausted from battle, the disease quickly brought down the Aztecs and allowed the Spanish to take over Mexico mostly unopposed. While the disease was a mystery for centuries, some modern researchers believe it's possible it was ordinary salmonella, passed on from the Spanish invaders. Since food safety and preventing contamination from bacteria hadn't been developed yet, it passed quickly through the Aztec people, but only infected a very few of the Spanish, who had more immunity to the illness due to greater exposure to it in Europe. This same strand of salmonella does exist today, but due to better hygiene, it's very rarely fatal.

Smallpox epidemics nearly wiped out Native Americans

Although your history classes might have taught you the Native Americans were mostly isolated tribes spread across North America, it turns out that's not actually true. Between early explorers visiting the shores of what would eventually be the United States in the late 15th century and the first attempts to colonize the so-called "New World" in the 16th century, smallpox (helped along by other diseases brought over by European explorers) killed about 90 percent of the Native American population. Estimates put the pre-Columbian Native American population at about 60 million people, according to PRI, which means smallpox and its disease buddies killed all but 6 million people, or 10 percent of the population of the entire world.

Europeans, who had been exposed to smallpox before, unknowingly carried the disease with them while they attempted to find a sailing route to India. The indigenous peoples of North America, similar to the Aztecs with cocoliztli, had never been exposed to the illness before, so during that 100 year gap before the first permanent colonies were founded, smallpox killed entire tribes and villages, a phenomenon known as a "virgin soil" epidemic.

So many Native Americans died that natural areas which had previously been meticulously maintained were allowed to grow unchecked, which scientists now believe absorbed enough CO2 from the atmosphere to lower the global temperature by a few degrees in the early 1600s.

The Antonine Plague ravaged Ancient Rome

The Roman Empire had numerous ups and downs throughout its history, and that includes several outbreaks of disease. From about 165 CE to 180 CE, the Antonine Plague spread unstoppably throughout the Roman Empire. Not just the city of Rome, but the whole thing. Named after Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, the plague is also sometimes called the Plague of Galen, the name of the physician from whom we get the most detailed writings.

According to the primary sources left by Galen and other Romans of the time, the plague's symptoms included diarrhea, vomiting, foul breath, and a rash all over the skin. Worse, it took two weeks for victims to die, often agonizingly. A very few who came down with the plague actually didn't die at all, then were seemingly immune after, according to Ancient History Encyclopedia. This has led modern scholars to believe that the plague was most likely smallpox, the symptoms are a match, and surviving it was like a really horrible vaccination.

Up to a third of the Empire perished from the plague, approximately 60-70 million people. The Antonine Plague is, in fact, considered the beginning of the end of the Roman Empire, as things began declining quickly for Rome afterward. A second outbreak rose about a century later, killing even more and further driving the Empire into collapse.

Athens had one of the earliest outbreaks in history

While illnesses has always been an issue for humankind, our ancient ancestors were much more spread out for a good part of history, so any outbreaks were fairly localized. Empires like Egypt and Babylon came along, but since little of that written history has survived to today, we don't have a lot of clear information on pandemics that may have hit back then.

One of the earliest plagues we do have fairly substantial info on was the Plague of Athens, which struck Greece in approximately 430 BCE. Pummeling the city for about five years, the plague caused fever, inflammation, blood coming from the mouth, and, eventually, diarrhea and bloody ulcers, according to The Atlantic. Victims were buried hurriedly in mass graves, although historians aren't sure exactly how many it killed, as this info wasn't recorded anywhere that still exists.

While most plagues of the ancient world lasted an extended amount of time, the Plague of Athens was different in that it wound down relatively quickly. This puzzled researchers for over 2,000 years, but a recent study might have uncovered the answer. The Plague of Athens could have actually been a very bad outbreak of Ebola. The symptoms match up almost exactly, but the length of time (Ebola outbreaks are typically much shorter than five years) and lack of physical evidence have kept it from being definitively named as the cause of the plague.

The Plague of Cyprian eliminated half of Alexandria

Just 100 years after the Antonine Plague and emerging alongside that pandemic's second outbreak, the Plague of Cyprian hit an already weakened Roman Empire in the middle of the third century CE. At its height, the plague was estimated to have killed about 5,000 people per day and the population of the city of Alexandria plummeted further as people fled, according to The Atlantic.

Paradoxically, even though it was 100 years later, we actually know less about the Plague of Cyprian than we do about the Antonine Plague. The reason is Galen, the physician who made highly detailed, prolific writings about the Antonine Plague. Unfortunately, he was long-dead by the Plague of Cyprian. We do have the writings of Cyprian, for whom the plague is named and who would later become Bishop of Carthage. Writing on behalf of the early Christian church, Cyprian's sermons and other writings have a lot of information about the plague, but Cyprian wasn't a doctor, so the writings are more from a layman's perspective.

While the Plague of Cyprian held some similarities to the Antonine Plague, such as gastrointestinal problems and lesions, it also had its own symptoms like hemorrhaging and blindness. This is how modern scholars are able to tell the second outbreak of the Antonine Plague and the Cyprian plague were two separate, simultaneous pandemics. Although we don't know exactly what the Plague of Cyprian was, modern historians believe it to have been a filovirus such as Ebola.

The 19th century had six major cholera pandemics

As we know from every movie set in the 1800s, tuberculosis was a big deal at that time, and getting it was effectively a death sentence. But deadlier still was cholera. In the 19th century, six outbreaks of cholera killed so many people that we don't even know exactly how many people it killed, due to different countries around the world each keeping their own separate counts of varying accuracy, including a few that didn't keep count at all.

Starting in 1817, cholera swept across the globe, according to the CBC. Many of the outbreaks were regional, and a seventh one occurred in the 20th century that is technically still ongoing, even though we do have some cholera vaccines today. The disease was mostly spread due to poor or non-existent sanitation methods, something which has improved over time and limited its transmission in modern times, though the illness still kills thousands each year.

The third cholera pandemic, stretching from 1846 to 1863, is considered to be the deadliest one, infecting just about every place on Earth at some point over nearly two decades, according to UCLA's Department of Epidemiology. While we don't know the exact death toll due to the aforementioned poor record keeping, we do know everywhere cholera struck, thousands died over dozens of outbreaks each year the pandemic went on.

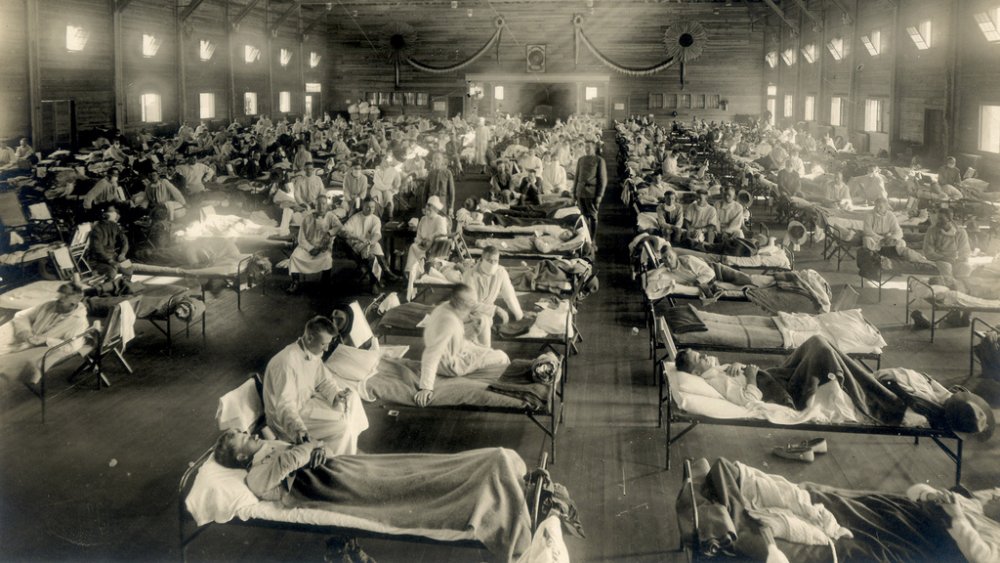

The Spanish flu was the modern world's deadliest outbreak

Every year, flu season comes and infects millions, though it's generally not deadly in healthy adults, and we do have influenza vaccines now, even if many people choose not to take them for fear the vaccine will somehow give them the flu (which is not how vaccines work, for the record). But sometimes, certain strains of the flu can be incredibly deadly, such as the so-called Spanish flu of the early 20th century.

At the end of the First World War in 1918, the Spanish flu began to erupt across the world, infecting and killing between 50 and 100 million people over the next two years, as much as 5 percent of the world's population at the time and more than both World Wars combined, according to Smithsonian Magazine. In fact, because of the war and the numerous injuries and illnesses affecting soldiers, the Spanish flu's spread became even worse due to already taxed medical supplies and staffing.

Over time, we learned the cause of the Spanish flu was something familiar to a lot of people today, because the virus is still around. According to the CDC, the H1N1 flu virus of avian origin, better known today as bird flu, was the culprit behind the 1918-1920 Spanish flu epidemic. The difference, of course, is the proliferation of modern medicine and better sanitation.

HIV is still going strong today

The epidemic of the modern age, HIV, has been ongoing for about 40 years, since the 1980s. While HIV is transmitted via blood and other fluids, it's still highly contagious and has infected about 70 million people worldwide, killing around half of those to date, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). While we've come up with ways to slow the virus, there's still currently no way of curing it completely, and sufferers will have to spend their lives either taking expensive drugs or dealing with compromised immune systems.

Unfortunately, things could be a lot better today, but we lost about a decade of research early on because the disease wasn't taken seriously by politicians or much of the medical field until the 1990s. Since the disease disproportionately affected gay men and users of injectable drugs in its earliest days, biases against those marginalized groups led some in authority positions to do nothing or, worse still, actively fight against researching or treating the virus.

Today, while the number of new infections is slowing, it's still not declining the way medical experts would like. The WHO has a stated policy of ending HIV/AIDS by 2030, but at current rates, this is beginning to look unlikely. Treatment, screening, and most importantly of all, education, are still needed if we hope to end the spread of HIV.

Yellow fever terrorized Philadelphia in 1793

While many of the deadliest outbreaks worldwide have been global pandemics that infect and kill throughout the world, there are some cases of very localized outbreaks that can also be highly fatal. Take, for instance, the yellow fever outbreak of 1793 in one of early America's most populated cities and the country's temporary capital, Philadelphia.

Yellow fever gets its name from the jaundiced skin of sufferers, whose liver and kidneys begin to shut down. Other symptoms included vomiting, internal bleeding, muscle pain, and, of course, high fever. Transmitted via infected mosquitoes, the outbreak was believed to have started from Caribbean refugees, fleeing from a yellow fever epidemic there, according to History. Within weeks, thousands were infected and dying, up to 100 a day. That may not sound like much, but considering the size of the city's population of the time, it was far too many. Over 5,000 people died, which made up over 10 percent of the city's residents.

What's particularly remarkable about this outbreak, though, is the sheer infrastructural collapse that occurred in its wake. Medical services were so overwhelmed and the city so unprepared to deal with the epidemic that Philadelphia's government was shuttered under the strain. The federal government, operating out of Philadelphia at the time, simply abandoned the whole city and evacuated in the face of the outbreak.

China's outbreak of the bubonic plague

While everyone is familiar with the bubonic plague in Europe in the 1300s, there have been three major outbreaks of the disease total. The first was the Justinian Plague, not known to have been the same disease until centuries later. The infamous Black Death was the second. The third outbreak, however, was just as deadly but is largely unknown. Starting in China in around 1855, the third epidemic of the plague eventually reached critical mass in 1894, spreading to Hong Kong, India, and ports all around the world.

Due to more advanced medical techniques of the time, researchers were able to finally determine the transmission vector for the plague. While rats had previously been hypothesized to be the cause of the illness, the third plague showed it was actually the fleas the rats carried that spread the disease. Also discovered was the particular organism that caused the illness, Yersinia pestis, according to the Journal of Military and Veteran's Health, which allowed early epidemiologists to link the epidemic to the two previous historical plagues.

The third outbreak killed around 15 million people, mostly in India due to heavy population density, and didn't end until 1959. The bubonic plague is still around, though, and a few hundred people still die of it each year.