Tribes That Have Zero Contact With The Outside World

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Humans are social creatures, and few people choose to isolate themselves from what is now a fully connected global society. Yet there are still pockets of the Earth that have virtually no interaction with outsiders. This is particularly true in areas that have thick forest, which makes the perfect cover for anyone who does not want visitors.

These uncontacted tribes are one of the many mysteries of the rainforest you've never heard of, which can lead to misunderstandings about the people who live there. There are plenty of strange facts about uncontacted tribes on Earth, but at the end of the day, even though most of these uncontacted peoples are the remnants of Stone Age tribes, they have complex, difficult lives that are just as important as anyone who lives in a city.

Unfortunately, most of these groups are under serious threat, so it's important to understand them as people, and not mere curiosities. Here are some of the few remaining tribes that have zero contact with the outside world.

The Sentinelese

Living on North Sentinel Island in the Indian Ocean, the Sentinelese are known as the most isolated tribe in the world. While they have had at least one friendly encounter with an outsider, they usually threaten anyone who comes near the shoreline, meaning the island is one of the few places on Earth we still haven't explored. It's not even clear how many people live there, with estimates ranging from 15 to 150.

"In recent years, there have been no attempts by anthropologists or anyone else to make official contact with the Sentinelese," Sophie Grig of the NGO Survival explained (via Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment). "Poachers and fishermen may illegally approach the island, but a hostile reception almost certainly awaits them." She made these comments in 2012, and would be proven right six years later when an American named John Chau snuck onto the island. Local fishermen witnessed the Sentinelese burying his body on the beach the next day. Despite this tragedy, others continue to try to make contact. Another American, Mykhailo Polyakov, was arrested for spending five minutes on North Sentinel Island in 2025.

The anthropologist Triloknath Pandit, who visited the island several times from the 1960s to 1980s, told Down To Earth, "We should not be in a great hurry to make contact with the Sentinelese. ... The government's responsibility should be to keep a watch over them in the sense no unauthorised [sic] people reach them and exploit them. Otherwise, just leave them alone."

The Shompen

Even when compared to the isolated and semi-isolated tribes nearby, exceptionally little is known about the Shompen, who live on Great Nicobar Island in the Indian Ocean. They made contact with outsiders during the 1800s, but have had hardly any contact since then. In 2014, the Anthropological Survey of India spent 40 days on the island gathering information about the tribe. While they only observed 78 Shompen, they estimate the population to be as many as 300.

Despite choosing to stay isolated, the Shompen are still citizens of India, and the government decided they should be able to vote. In 2014, a polling station was transported deep into the interior of the island, and 60 members of the tribe cast their vote for their local member of parliament.

But plans to develop Great Nicobar Island could wipe the tribe out completely. India intends to spend $9 billion to turn part of the island into "the Hong Kong of India." There are plans for a massive port, an airport, industrial works, a military base, and tourist-friendly destinations. While the Indian government has tried to downplay the effect that such a project would have on the Shompen, experts say it will wipe them out completely. Dozens signed an open letter saying, "If the project goes ahead, even in a limited form, we believe it will be a death sentence for the Shompen, tantamount to the international crime of genocide" (via The Guardian). As of 2025, the plans for development are unchanged.

The Awá

The tragic genocide of Brazil's indigenous peoples affects many different tribes, but none is more endangered than the Awá. While most of the Awá have chosen to make limited contact with the outside world, some are still uncontacted. Members of a neighboring tribe, the Guajajara, caught some of these remaining uncontacted people on video in 2019. While the uncontacted Awá want to stay that way, they are not always given a choice.

In theory, since 2003, the uncontacted Awá's land is protected, and one of the places the public isn't allowed access to in the Amazon. But the reality is much more tragic. Ever since iron ore was discovered in the same area of the Amazon in the 1960s, they have faced incursion from the outside world looking to make a fortune. In the 21st century, it is the illegal loggers who caused the most problems for the Awá. There are documented cases of loggers threatening and even killing members of the tribe — including a young girl — but experts believe most of these cases go unreported.

"The Awá and the uncontacted Awá are really on the brink," Fiona Watson of the charity Survival International told The Guardian. "It is an extremely small population, and the forces against them are massive. They are being invaded by loggers, settlers, and cattle ranchers. They rely entirely on the forest. They have said to me: 'If we have no forest, we can't feed our children and we will die.'"

The Kawahiva

The Kawahiva are a nomadic people living in the Amazon. They had interactions with explorers as far back as 1750, but due to their constant movement, no one in the outside world was sure if they still existed until 1999. Most information researchers have gathered about them comes from the items they leave behind when they move, such as arrowheads, hammocks, and baskets. In 2011, researchers captured footage of several tribe members on video for the first time.

Today, it is estimated that there are approximately 35 to 40 Kawahiva, up from around 20 in 1999. One of the reasons their numbers have not increased more in that time is that they were being slaughtered. In 2005, an investigation was launched into reports that the Kawahiva were being massacred by illegal loggers, and 90 people were arrested, although the prosecutions do not seem to have gone anywhere. Other court cases seeking rights and protections for the tribe have had positive results, but loggers and others are still invading the territory, which has yet to receive the highest classification of protection from the Brazilian government.

The nearest town to the tribe's land is Colniza, reportedly the most violent town in the entire country. Many living there are angry that the government protects the tribe, which means they can't expand and take the land. There is even a conspiracy theory that the tribe was moved to that location on purpose, just to keep the locals from developing the forest.

The Korubo

The interactions that the Korubo tribe of Brazil has had with the outside world have been particularly brutal. Members have been involved in violent clashes with outsiders like loggers since at least the 1920s. While uncontacted tribes killing outsiders who invade their land is not unusual, it is the particular way that the Korubo kill their enemies that is notable. Their nickname is, after all, the caceteiros, which means ”head bashers." Male members of the tribe carry around large clubs, and witnesses have seen them used to kill several people.

Raimundo "Sobral" Batista Magalhães was an expert on indigenous issues who had frequent contact with members of the Korubo tribe. Regardless of this relationship, he was clubbed to death in 1997, when there was a misunderstanding over a tarp he had given the tribe. Two of his colleagues saw the attack, but were across a river and unable to intervene. The Brazilian government did not prosecute the man who killed Sobral, as it was determined that the Korubo cannot be held to legal standards they have no knowledge of.

Sydney Possuelo, for years the undisputed expert on isolated peoples in the Amazon, made contact with a splinter group of the Korubo in 1996. Since then, the small group has chosen to have some contact with aid workers, including receiving vaccines. But this also meant that Possuelo spent time with the man who had killed his friend, Sobral, although he claimed to have no malice towards him.

The Flecheiros

While little is known about most uncontacted tribes, for obvious reasons, even less is known about the Flecheiros – the Arrow People — than the other uncontacted tribes located in the same area of the Amazon. Some tribes have members who choose at least limited contact with the outside world, but the Flecheiros choose to remain completely isolated.

Sydney Possuelo, Brazil's foremost expert on isolated tribes at the turn of the century, said this was the way it needed to stay. "It's not important to know any of that to protect them," Sydney Possuelo told National Geographic. "Once you make contact, you begin the process of destroying their universe." While avoiding having any actual contact with the Flecheiros, Possuelo took expeditions deep into the Amazon to determine which areas the tribe traveled between by finding the camps and tools they left behind. Possuelo said, "The work we are doing here is beautiful, because they don't even know we're here to help them. We have to respect their way of life. We're not going to pursue them. The best thing we can do is to stay out of their lives."

Unfortunately, run-ins with outsiders have turned deadly. In 2017, there was a horrific massacre: Some Flecheiros were hunting for turtle eggs on a riverbank when they were confronted by gold miners, and 10 members of the tribe were murdered. The only reason this slaughter even came to light was that the miners bragged about their crime at a bar.

The Carabayo

The Carabayo had numerous negative interactions with outsiders over the past few centuries, including slave traders. This resulted in the tribe becoming increasingly isolated to protect itself.

It was only in 2012 that anyone captured photographic evidence of their existence. While protected by Rio Puré National Park in Colombia, it was important to know their location and other basic information in order to protect the Carabayo more effectively. For this reason, reconnaissance flights searched the Amazon for evidence of the tribe. The flights discovered several dwellings used by the Carabayo and at least one other isolated tribe, making the risk of disturbing them worth it. "Although the Park's objective is to provide shelter for this indigenous group, anthropological data was needed to inform the formulation of official governmental legislation and policies to safeguard both the integrity of the region and the survival of this group," Liliana Madrigal, co-founder of ACT, told Mongabay.

One piece of information we do have about the Carabayo is a list of 50 words in their language. Unfortunately, this list was compiled when a family was kidnapped by the Colombian military in the 1960s. Although an unfortunate means of obtaining such important information, it led to new insights into the tribe. "While this family was held captive, speakers of all living languages of the region tried to communicate with them but failed," Frank Seifart of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology explained. "Researchers thus concluded that Carabayo was not related to any living language in the region."

The Tagaeri

In 1968, when missionaries forced the settlement of the Waorani people in Ecuador, a group broke away to continue their isolated, nomadic lifestyle. Called the Tagaeri, their name originates from the leader of the small group.

Since then, they have resisted contact, but incursions into their territory have turned what was once known by its neighbors as a peaceful people into one with a reputation for being violent. Several outsiders appear to have been killed by the tribe over the years, including three illegal poachers who were found killed in the Tagaeri's area of the rainforest between 2005 and 2008. One could fairly argue, however, that the Tagaeri are merely attempting to protect themselves. In 2008, at least five members of the tribe were murdered by illegal loggers. Other massacres occurred in 2003, 2006, and 2013, killing dozens and leading to two girls being kidnapped.

Finally, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights got involved. In a precedent-setting case, it found that the Ecuadorian government has a responsibility to make sure isolated tribes are protected from this kind of violence. "This judgment of the Inter-American Court is the result of many years of struggle and is a guarantee of the rights to territory for peoples in isolation, so that they can live without the threat of oil, mining, and other threats. This is a milestone for all Indigenous peoples living in isolation in the region and throughout the world," Juan Bay, President of the Waorani Nationality of Ecuador, said (via Amazon Watch).

The Mashco-Piro

Many uncontacted peoples are dwindling in numbers due to the many pressures put on them by their isolation, as well as the incursions of the outside world. So it is positive that the population of the Mashco-Piro tribe — also known as the Nomole – appears to be growing. In fact, with an estimated 750 members, the Mashco-Piro are believed to be the largest uncontacted tribe on Earth. This is an astonishing comeback for the Peruvian tribe, since past interactions with outsiders have been violent, including when the tribe was almost wiped out in 1894.

This does not mean that the Mashco-Piro are not in danger today. In the 21st century, illegal logging poses a significant threat to their safety, and attempting to escape the logging also puts them in contact with tourists in Manu National Park, which can be equally dangerous. In 2012, a forest ranger was attacked, and over a decade later, in July 2024, photos showed a large group of Mashco-Piro close to a logging concession. The inevitable happened when two loggers were killed by the tribe just weeks after this sighting.

Enrique, a member of the neighboring Yine tribe, told Survival International, "We've shared a territory with the uncontacted people for many years, since I was a child ... and they've never done anything bad to us. They see us around, but they don't bother us. But that was years ago. Now, since there have been logging concessions, they feel increasingly pressured and upset because the companies have assaulted them."

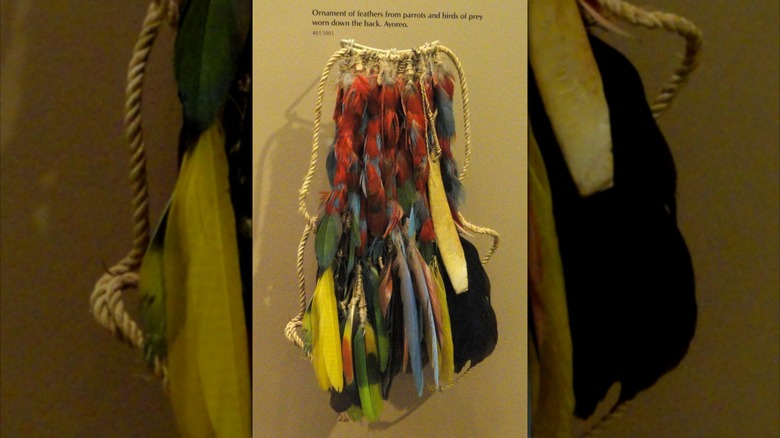

The Ayoreo

There are approximately 5,600 members of the Ayoreo tribe living on the border between Bolivia and Paraguay, although only around 100 of them — a subgroup known as the Totobiegosode — choose to maintain no contact with the outside world.

This has become increasingly difficult since the 1930s. A large Mennonite community, fleeing persecution in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, moved into the area previously occupied by the Ayoreo and began ranching and farming. This influx has only increased in the 21st century, as the land becomes more valuable than ever, and more people see a way to make money in the area. By 2010, the deforestation had become so severe that experts worried the rainforest would be gone within a generation. Despite some protections for the area, deforestation continues today, and even well-intentioned outsiders can have a negative impact on the Ayoreo. In 2010, London's Natural History Museum was planning to send a large group of researchers to find and catalog new flora and fauna in the area, but called off the expedition after campaigners pointed out the dangers of accidentally interacting with the tribe.

However, the Ayoreo don't have many other options, even when they choose (or are forced to) finally interact with the outside world. The majority of the tribe now lives in wider society, but they are so badly discriminated against that several members have recently chosen to return to their traditional way of living and end contact, opting to live in the rapidly disappearing rainforest.

The O Hongana Manyawa

The O Hongana Manyawa live on the Indonesian island of Halmahera, and the tribe is more commonly called the Togutil, but this name is highly offensive. Indigenous rights advocate Roem Topatimasang told the China Global South Project, "[Outsiders] call them 'Togutil,' which means 'primitive' or 'stupid.' That kind of language erases the dignity and depth of their culture."

While those members of the tribe who live on the coast have limited contact with outsiders, those who stay more inland choose to remain isolated. Loggers and others who come onto their lands are angrily told to leave. However, the O Hongana Manyawa are now under the most severe threat they have ever faced. Their island and the surrounding area are being mined for nickel. This is causing unbelievable suffering to the inhabitants. One explained, "They are poisoning our water and making us feel like we are being slowly killed." Another said no one had asked the tribe if they could mine on their land: "I do not give consent for them to take it ... tell them that we do not want to give away our forest" (via Survival International).

The cruel irony is that this destruction is being carried out in the name of environmentalism: the nickel mines are necessary for producing electric car batteries. One Hongana Manyawa man told Survival International, "If you want to buy nickel from a mining company, please first ask where it's from. If it comes from Ake Jira in Halmahera, then please don't buy it."