Things That Came Out About One-Hit Wonders After They Died

Achieving the status of one-hit wonder is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it's an incredible feat to rise up through the music industry and record and release a piece of music that sells a lot of copies and makes a lot of people happy. But then it's somewhat embarrassing when such an artist can't re-create that success, going down in the annals of cultural history as a flash in the pan who was only capable of creating three to four minutes of special art, as opposed to the singers and bands that pump out hits for decades.

Out of the spotlight as quickly as they entered it, these single-hit-crafting dynamos often fade into obscurity. Years go by, and as they're fated to do, those one-hit wonders die. If their deaths are publicly acknowledged, that's usually when the private stuff goes public, when information previously known only to the musicians' inner circles is shared and amplified, everything from family secrets to impressive but low-key achievements, or even the reasons behind their deaths. Here are some things discovered after the deaths of those artists who had just one song enter the Top 40 in the U.S., or who landed a hit so memorable that it overshadowed all their other, less successful work.

Sheb Wooley made a famous scream

He would hit the country charts with some minor hits in the latter part of the 1960s, but Sheb Wooley made it onto the top of the pop list just once, with the 1958 novelty hit "The Purple People Eater." Wooley wrote the goofy song himself, which concerns a one-eyed, one-horned alien with the power of flight who comes to Earth to join a rock band and eat purple people.

Seven years after first being diagnosed with leukemia, and following a brief emergency hospitalization in Nashville, Wooley died in September 2003 at age 82. Wooley's primary profession was acting, and he appeared almost exclusively in mid-20th century Western television series and movies. His characters often died on-camera, and he delivered such good, agonizing death screams that one of them was preserved for posterity and relentless use in the decades to come. The "Wilhelm scream," often used by movie sound designers, is named after the doomed Private Wilhelm in the 1953 movie "The Charge at Feather River," but it stemmed from 1951's "Distant Drums." Following Wooley's death, an investigation revealed that the singer and actor's uncredited yell in "Distant Drums" was the original "Wilhelm scream."

Pete Burns didn't want to get old

Dead or Alive had a brief moment of fame when its delirious dance tune "You Spin Me Round (Like a Record)" hit No. 1 in the band's native U.K. and No. 11 in the U.S. in late 1984. Follow-up singles like "Brand New Lover" stalled in much lower positions, leaving main musician Pete Burns free to embark on a solo career and pursue reality TV gigs.

After sustaining a medical event in which his heart stopped, Burns died in October 2016 at the age of 57. Burns seemed to know beforehand that he wouldn't live to old age. "If you're going to be cynical there's one man who would have wanted to die young — and that was Pete Burns. He didn't want to get old," Burns' friend and producer Pete Waterman told The Mirror. From the mid-1980s on, Burns attempted to fend off the effects of aging with medical assistance. He submitted to around 300 cosmetic surgeries in his lifetime.

Walter Scott vanished and was murdered

One of the few bands named after its drummer, Bob Kuban and the In-Men mixed rock with horns and appeared on the higher part of the pop chart exactly once. In 1966, the band made it to No. 12 with the cautionary tale "The Cheater." A year later, and after some further singles didn't make an impression, lead singer Walter Scott left the band to pursue a solo career.

Unfortunately, his records sold poorly, and Scott joined a succession of cover bands until Kuban called him in 1983 for an In-Men reunion concert in St. Louis, where Scott still lived. Just before rehearsals, Scott disappeared. His wife, Joann Scott, said he left home on December 27, 1983, and his car was found at the St. Louis airport. Joann Scott moved in with Jim Williams, whose wife, Sharon, had been found dead in her car two months before Walter Scott vanished. Citing abandonment, Joann Scott divorced the missing singer and married Williams. Believing their son to have been murdered, Walter Scott's parents persuaded police to investigate. In 1987, four years after he disappeared, Walter Scott's whereabouts were discovered: He'd been tied up, shot, and left in a cistern in Jim Williams' backyard. Williams was convicted on a murder charge and died in 2011 while serving a life sentence. Joann Scott Williams agreed to a plea deal and was imprisoned for 18 months for interfering with the prosecution.

Randy VanWarmer was launched into space

Ultra-mellow singer-songwriter Randy VanWarmer's first hit single, "Just When I Needed You Most," went to No. 4 on the pop chart and No. 1 on the adult contemporary chart. He'd never come anywhere near the Top 40 again, but he kept making albums for himself and finding some small successes in country music, where he was an in-demand songwriter for the likes of Alabama and the Oak Ridge Boys.

In January 2004, the 48-year-old VanWarmer died from complications of leukemia. The last music he created was "Randy VanWarmer Sings Stephen Foster," an album of covers of old American chestnuts like "Oh! Susanna" and "Beautiful Dreamer." He played every instrument on the record himself and worked on it after he was diagnosed with leukemia, news he didn't widely share. The Foster album hit stores in 2006, and a year after that, VanWarmer made the news again when a portion of his cremains were shot into space as part of a private spaceflight.

Joan Weber's whereabouts were discovered after her death

Right when early rock 'n' roll songs by male singers changed the American musical landscape, a slew of female performers kept alive the vocal jazz age with dramatic ballads about romance and heartbreak. There were venerable hitmakers in this vein such as Doris Day, Patti Page, and Connie Francis, but there was also Joan Weber, who became a one-hit wonder when her overwrought "Let Me Go Lover" occupied the No. 1 spot in 1955. Right as the song was flying off record store shelves, Weber gave birth to a daughter, and after she took some time off, Columbia Records dropped her. Some potential comebacks singles couldn't restore Weber's fame, and she left the industry entirely.

Weber became so tough to find that in 1969, when Columbia Records repeatedly attempted to send Weber royalty checks on her old recordings, they were returned because the singer's address couldn't be pinpointed. She died in May 1981, at which point her whereabouts were revealed to the public. Heart failure had killed Weber at the age of 45, and she'd died in the Ancora, New Jersey, mental health facility where she'd been living for some time.

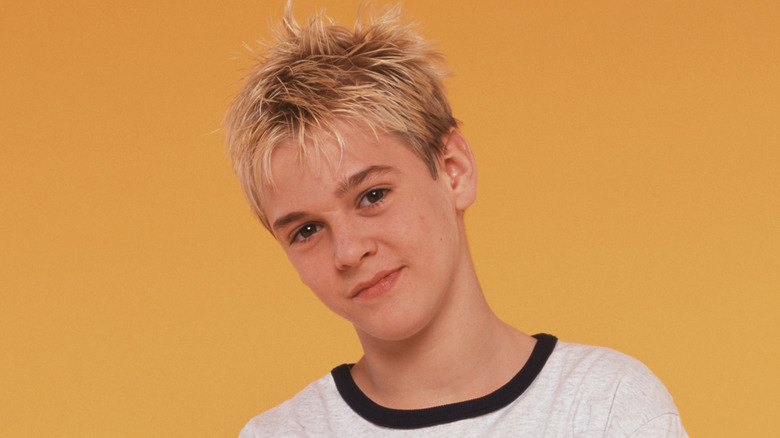

Aaron Carter's mental health struggles

Just after the Backstreet Boys ushered in a new wave of sweetly harmonizing boy bands in the late 1990s, in came the solo acts performing similar material. One beneficiary of the fad was Aaron Carter, younger brother of the Backstreet Boys' Nick Carter. He was marketed to a tween demographic with songs like his only entry to break into the Top 40, "Aaron's Party (Come Get It)" which reached its peak of No. 35 when Carter was 13 years old.

In November 2022, a house sitter arrived at Carter's home in Lancaster, California, and found the singer dead in a bathtub surrounded by drugs and drug-taking equipment. According to an autopsy, he'd ingested large amounts of anti-anxiety medication and aerosol inhalants, lost consciousness, and died by drowning. He was 34.

The full extent of Carter's health problems only became known after he died. In the 2025 documentary series "The Carters," the singer's twin, Angel Carter Conrad, discussed a number of harrowing episodes. Disclosing that her brother had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, Carter Conrad revealed that the musician fantasized about mass murder and killing his brother's pregnant wife. He began to acquire an array of firearms and at one point, drove to Nick Carter's home with one of his guns. That led to a request for a restraining order, publicly acknowledged by Nick Carter on social media with vague allusions to his brother's troubles.

Ernie K-Doe actually liked his mother-in-law

It's a long-standing cliché that married men can't stand their mothers-in-law, who are often depicted in pop culture as overbearing and obnoxious. Mother-in-law jokes are almost as old and trite, and it's in that tradition that Ernie K-Doe, a New Orleans R&B singer and local fixture for decades, recorded a novelty song on the subject written by jazz legend Allen Toussaint. His only significant chart success, K-Doe's "Mother-in-Law" went to No. 1 in 1961.

K-Doe, whose real name was Ernest Kador Jr., died in New Orleans in July 2001 after his liver and kidneys failed. He was 65. All ribbing aside, K-Doe got along well with his real mother-in-law, or at least the parent of his second wife, Antoinette K-Doe. Because the musician's spouse hadn't arranged for a burial plot for her husband at the time of his death, she accepted an offer from Anna Ross Twitchell, a member of an organization that preserves New Orleans' many old and lavish cemeteries. Ross Twitchell gave away a spot in a tomb in St. Louis #2 Cemetery to be used to inter K-Doe. Later laid to rest in the same tomb, not far from K-Doe: Leola Clark, the late musician's mother-in-law, with whom he reportedly got along just fine.

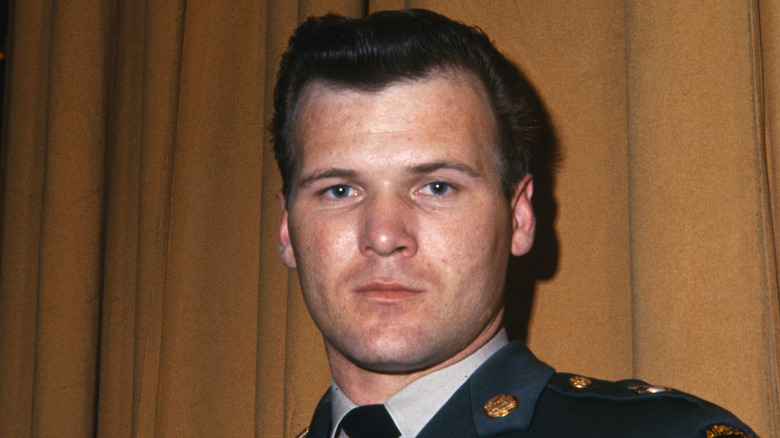

SSgt. Barry Sadler's secret political adventures

Not everyone in the United States in the late 1960s was a young, Vietnam War-protesting hippie. President Richard Nixon spoke of a "silent majority" of conservative Americans who supported the war and troops fighting overseas, who probably didn't know that the Vietnam War was way worse than anyone thought. That pro-intervention sentiment powered the military march "Ballad of the Green Berets" all the way to No. 1 in 1966, co-written and performed by a real-life veteran, Staff Sgt. Barry Sadler. A rushed second single with similar themes and a nearly identical sound, "The A Team," couldn't repeat the fortunes of "Ballad of the Green Berets," and Sadler's musical career came to an end shortly thereafter.

In what local investigators believe was part of a botched robbery, Sadler was shot in the head as he climbed into a cab in Guatemala City, Guatemala, in September 1988. Sadler was diagnosed with brain damage and sent back to the United States for treatment at Veterans Administration hospitals in Cleveland and Murfreesboro, Tennessee. While receiving care at the latter in November 1989, Sadler died at age 49. That final chapter helped fill in some of the blanks regarding what Sadler had been up to since dropping out of the music scene. He'd realigned himself with U.S. military operations and had been living in Guatemala since about 1984. He'd been tasked with providing weapons training to anti-communist Contra fighters.

Charles and Eddie were going to make a comeback

Angelic melodies that seemed to come straight out of the 1960s, combined with the thumping beats and pristine production of the '90s, fueled "Would I Lie to You," a No. 13 hit in the U.S. (and a No. 1 hit in the U.K.) for pop-soul duo Charles and Eddie. That 1992 commercial triumph wouldn't be repeated; subsequent singles couldn't even make the Billboard Hot 100, and Capitol Records dismissed the act.

The Charles of Charles and Eddie, Charles Pettigrew, died in Philadelphia in 2001 at age 37 from the effects of cancer. He'd been diagnosed with the disease several years earlier but kept that information extremely private. "He never told me was sick," Eddie Chacon told The Guardian in 2020. The pair considered themselves a one-hit wonder who deserved more than 15 minutes of fame. In the months leading up to Pettigrew's surprising death, Chacon had been trading demo tapes with him, and the two had made secret plans to revive the Charles and Eddie project and begin recording again.

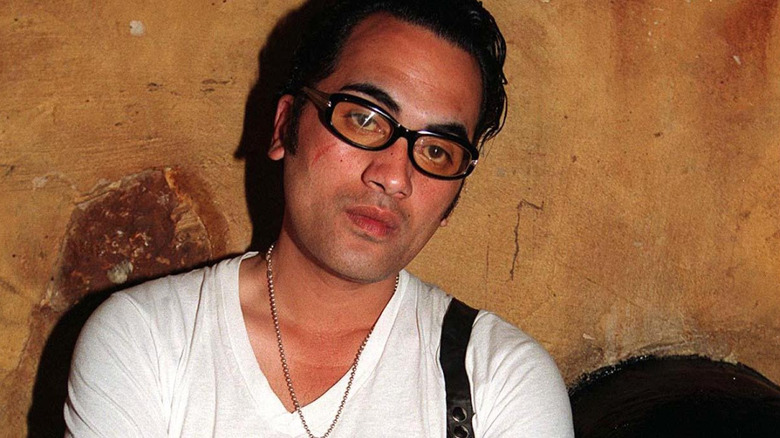

OMC's Pauly Fuemana had a rare disease

One of the sunniest-sounding songs of the 1990s, OMC's "How Bizarre" contained multitudes of dark humor and terrors. The name OMC is short for "Otara Millionaires Club," referring ironically to the low-income suburb of Auckland, New Zealand, where the band formed, and the song's bright classical guitar riff propelled singer-rapper Pauly Fuemana's emotionless story about getting car-jacked. "How Bizarre" was a major hit virtually everywhere in 1996, including New Zealand, Germany, the U.K., and the United States.

Eight days before he was set to turn 41 years old in January 2010, Fuemana died suddenly. The initial cause of death was thought to be respiratory failure, but it would take an investigation and the issuance of a death certificate after the fact to find out what really killed the primary member of OMC. It transpired that Fuemana had been privately diagnosed with progressive demyelinating polyneuropathy, a neurological and autoimmune disease. Fuemana had developed pneumonia as a symptom of the disease, which manifests as progressive, body-wide nerve failure. It's a rare disease, and to those who get it, it's only deadly in about 1 in 10 cases.

Sister Sourire was in dire financial trouble

In 1963, Sister Luc Gabrielle of the Fichermont convent in Belgium paid a Philips Records facility to record and press a limited run of records of religious songs. Philips executives were so enchanted that the label publicly released the album, branding the lead performer as Soeur Sourire, or "Sister Smile." She became known as "The Singing Nun" in the U.S., where "Dominique," a French-language folk tune about 12th-century figure Saint Dominic, went to No. 1. Soothing, religious, and calm, it seemed to work as an audio salve for a nation shocked by the November 1963 assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

In 1966, Sister Luc Gabrielle questioned her beliefs, left her religious order, and moved into the secular world under the name Jeanine Deckers. Twelve years later, it emerged that the musician faced a tax bill of $126,000 on her recordings, which she was unable to pay as she'd given all of her financial property to her convent. Those money problems grew more serious and seemingly insurmountable, a fact learned after Deckers died in April 1985. Police discovered the body of 52-year-old Deckers in her home in Wavre, Belgium, alongside a friend, soon identified as her partner, Annie Pescher. Deckers and Pescher died by suicide, and the former Singing Nun wrote a note explaining her extreme sadness over her years-long financial struggles with the Belgian government and the problems she had running a school she'd opened to serve kids on the autism spectrum.

Benjamin Orr and Ric Ocasek reconciled

It's part of the story of the Cars that the Boston band was one of the most successful and notable acts of the New Wave era. Lead vocal duties were split between Benjamin Orr (he handled "Just What I Needed" and "Drive") and Ric Ocasek (he did "Magic" and "You Might Think"), but neither singer could parlay his Cars fame into a stellar solo career. They're both one-hit wonders: Orr's "Stay the Night" reached No. 24 in 1986, the same year that Ocasek's "Emotion in Motion" made it to No. 15.

"The best of friends forever" is how Ocasek characterized to Rolling Stone in 2011 his friendship with Orr, which began in the 1960s and included stops in the bands Milkwood and Cap'n Swing before the Cars. The relationship had fractured by the late 1980s, at which point Orr was touring in his own bus away from the band and barely talking to Ocasek. "He was drinking a little much," Ocasek said. When the Cars officially split in 1988, Orr and Ocasek didn't speak for years, until they rekindled things while making material for a Cars DVD in 1999. Within a year's time, Orr died of pancreatic cancer; Ocasek died in 2019.

Larry Henley inspired Bobby Goldsboro

Mixing doowop with elements of R&B and wacky falsetto vocals made the Four Seasons very popular in the early 1960s, and the Nashville vocal trio the Newbeats capitalized on the sound. Its one and only hit, "Bread and Butter," which weaves allusions to breakfast into a tale of romantic woe, hit No. 2 in 1964, and it's the only song for which the Newbeats would be remembered. The group stayed together despite the lack of hits until 1974, at which point main singer Larry Henley went solo. He later co-wrote Bette Midler's signature ballad "Wind Beneath My Wings." In December 2014, Henley died at age 77 in Nashville, owing to the effects of Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease.

Henley's music, both with and without the Newbeats, could be perceived as corny, and he directly inspired another star who peaked in the 1960s with schmaltzy, melodramatic songs. Bobby Goldsboro, best known for sentimental stuff like "Watching Scotty Grow" and "Autumn of My Life," recorded his biggest hit because Henley suggested it. That song was "Honey," a No. 1 hit in 1968.

Lovin' You is about Maya Rudolph

There's not all that much to "Lovin' You," the debut hit single from 1975 by Minnie Riperton. It serves as a vehicle for the singer's remarkable voice, with a range that could reach the ultra-high whistle register. The No. 1 smash plays like a love ballad, with Riperton purring and wailing her way through lyrics of adoration and devotion. The only recording from Riperton to ascend the pop chart, it ends with a lengthy trail of what sounds like improvised, nonsensical vocalizations.

After being diagnosed with breast cancer, Riperton underwent a mastectomy and embarked on a public education campaign to spread awareness of the disease. She died from it at age 31 in July 1979. Survivors included her husband and children, among them 6-year-old Maya Rudolph. The future actor and "Saturday Night Live" cast member was the inspiration for the often-misinterpreted "Lovin' You," and her mother name-checked her on the full-length, album version of the song. The demo didn't have lyrics, just Riperton singing "Maya, Maya" over and over, and the singer used it to soothe her then-baby daughter. When the final version of "Lovin' You" was made, the "Maya, Maya" element was preserved in the song's closing moments.

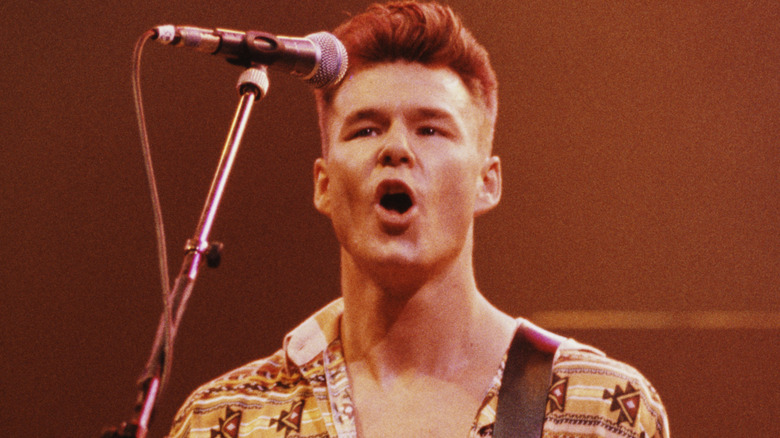

Amy Winehouse loved rap

Mixing '60s R&B tropes (and fashions) with jazz and confessional songwriting that often touched on her issues with substance use, Amy Winehouse's "Rehab" became a Top 10 hit in the U.S. and won the singer record of the year and song of the year at the 2008 Grammy Awards. Winehouse is also a one-hit wonder who vanished after winning the Grammy Award for best new artist due to tragic circumstances. On a Saturday afternoon in July 2011, Winehouse's body was discovered in her apartment in north London. An inquest concluded that the singer died from a fatal case of alcohol poisoning, as there was enough in her system that it cut off her ability to breathe.

Early in her career, the singer had engaged writer John Marrs in a 2004 interview, which wasn't published until three years after she died. She'd shared her earliest musical aspirations. "I wanted to be in Salt-n-Pepa so much that my friend Juliet and I started our own band, Sweet-n-Sour, when we were 9. I was Sour," she recalled, according to HuffPost. In adulthood, Winehouse harbored a powerful crush on the rapper Nas. Following her death, Nas told XXLMag that he was the subject of the mystery-shrouded "Back to Black" album cut "Me and Mr. Jones." Winehouse's amorous lyrics reference a man with a September 14th birthday and a daughter called Destiny. His real name: Nasir Jones.

Grief may have killed Van McCoy

"Disco" wasn't just one kind of dancing. The messed-up history of disco made room for lots of music and lots of individual dance crazes people could try out in the countless clubs that popped up around the U.S. in the latter half of the 1970s. One of those dances was the Hustle, and it got a big boost when music industry lifer Van McCoy released a song by that name in 1975. "The Hustle" perpetuated and popularized the dance, even though the song was instrumental except for studio singers shouting "do the Hustle," and did not give any instructions. McCoy had been recording for years before his massive smash, and he'd keep recording until the end of the 1970s, never again making the Top 40.

In late June 1979, McCoy sustained a heart attack at his home in Englewood, New Jersey, and he'd fallen into a coma upon arrival at a local hospital. About a week later, McCoy died at age 39. His death at such a young age may have been the result of overwhelming grief, according to his estate-approved biographers. The musician overworked himself to deal with the brain hemorrhage-caused death of his mother in 1973, which was then followed by the death of his grandmother, who helped raise him, less than three years later. McCoy was so overcome by sadness that his father joined his touring entourage to provide moral support. McCoy's condition apparently deteriorated until his ultimately fatal cardiac episode in 1979.

Tommy Page had a lot of mental health difficulties

After budding singer-songwriter Tommy Page gave his self-recorded demos to Sire Records executives he cornered one night at the dance club where he worked, he landed a record deal and scored a minor hit in 1989 with "A Shoulder to Cry On." That won Page a spot as the opening act on a tour for New Kids on the Block, and that boy band's Jordan Knight helped Page write a song on a hotel piano one night. That became the love ballad "I'll Be Your Everything," which hit No. 1 in April 1990 and made Page one of America's biggest teen idols for a few months.

Moving on from an active recording career, Page stayed in the music business, working as an executive at Warner Bros. Records and Pandora before becoming the publisher of the music industry trade magazine Billboard. His former employer reported that Page was found deceased on March 3, 2017. Page died by suicide, according to close associates of the singer. His personal experiences with mental illness and suicidal ideation were not well known to the public at large or to the vast number of artists with whom he'd worked. Page was 46.

Stuart Adamson's sad final days

There's a name for that particular style of music that had a big moment in the '80s — soaring melodies, ringing guitars, and inspiring and anthemic lyrics were the recipe for "the Big Music." Among its adherents: Simple Minds, U2, and Big Country. The Scottish band made its guitars sound like bagpipes on its songs, and that was one of the hooks in Big Country's 1985 single "In a Big Country," a No. 17 hit in both the U.S. and the U.K.

In December 2001, the body of Big Country lead singer Stuart Adamson was discovered in a hotel room in Hawaii. The musician had died by suicide at the age of 43. The discovery marked a tragic end to Adamson's fraught final years and a frantic search by family and friends when he went missing. Coping with depression and alcoholism amidst the decline of Big Country and the end of his marriage, Adamson found sobriety for about a decade until a relapse in the early 2000s. He was arrested and arraigned on a drunk driving charge in Nashville, and on the same day that his second spouse filed for divorce in November 2001, Adamson disappeared.

Big Bank Hank may have stolen his rhymes

It's an undeniable element of the story of the Sugarhill Gang that the trio, made up of Wonder Mike, Master Gee, and Big Bank Hank and assembled by Sugar Hill Records in 1979, brought the then-underground party phenomenon known as rap music to the mainstream. The group's "Rapper's Delight" eked into the Top 40 of the pop chart in 1979, making it the first-ever hit rap single.

Following a cancer diagnosis and a regimen of treatments, Big Bank Hank, or Henry Lee Jackson, died in November 2014 at age 58 in Englewood, New Jersey, the same city where he'd worked in a pizza parlor when he was approached by producer Sylvia Robinson in 1979 to be a part of what would become the Sugarhill Gang. At that time, Jackson was working as the manager for Bronx rapper Curtis Brown, who performed under the names Grandmaster Caz and Casanova Fly. In an interview with VladTV days after Jackson's death, Brown reiterated and confirmed in minute detail just how his manager allegedly secured himself a spot in the group. Rather than advocate for his client or present a demo tape to Robinson, Jackson took a lengthy set of lyrics written and previously performed by Brown and used them as an audition piece and then in the recorded version of "Rapper's Delight," going so far as to self-identify as Casanova Fly.

Dan Hartman didn't tell the world that he had AIDS

In the comparatively unenlightened 1980s, very few celebrities publicly disclosed if they identified as members of the LGBTQ community. The social and political climate of the time was much more hostile, and a career could end quickly for an openly gay performer. Thus, hit-making musicians kept that aspect of their identity secret, and it only emerged after they died. The 1980s and early 1990s were also beset by AIDS and a deep, collective fear of the deadly disease. At first, gay men were one of the primary populations affected — and decimated — by the immune disorder that can be acquired through the HIV virus. Homosexuality and AIDS were thus inexorably linked in the public consciousness, and so it was also damaging for a celebrity with AIDS to let the world know that they were suffering and likely dying.

Some famous musicians who identified as gay men died of complications of AIDS. Their orientation, and how they had AIDS, wasn't revealed until after they'd died. Dan Hartman played in the Edgar Winter Group in the 1970s, and he took the lead on one of that band's biggest hits, "Free Ride." His solo career produced just one smash, the 1984 soft rock radio staple "I Can Dream About You." When Hartman died at the age of 43 in 1994, his manager told the media that the cause of death was a brain tumor. Hartman had told only very close associates that he was gay, and that he'd probably been exposed to HIV at the end of the 1980s. The brain tumor with which he was diagnosed was linked to his AIDS-positive status.

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction or mental health issues or is struggling or in crisis, contact the relevant resources below:

- The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

- The Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

-

Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org