Why Different Blood Types Can't Be Mixed

Blood. It's pretty simple, right? It's the red junk that comes out when you fall down. It's what vampires eat when they're feeling like Count Snackula. It's one of about five bodily fluids that can change the MPAA rating of a movie. Running low? Head to your local hospital and have them top you off. Got too much? Grab a couple of needles and a rubber tube and give some to your buddy or your cat.

Not so fast, Bleedy Gonzales. Before you get the old tissue oxygenation oil changed, there's a whole lot of science to be done, because even the slightest mistake in this relatively routine procedure can lead to a violent, horrifying death.

The long, gross history of stuff that doesn't belong in your veins

First, a little history. People have been swapping their wet red cells since around the time that Shakespeare was mercilessly draining his tragic protagonists of theirs. The history of transfusion, according to the American Red Cross, goes back to the 17th century, with British physician William Harvey first describing blood circulation in 1628. Not long after that, folks started experimenting with trading their precious inside juice, and in 1665, another Englishman by the name of Richard Lower was managing to keep dogs alive via infusions of fresh blood. The following year, a fellow named Jean Baptiste Denis conducted the first human blood transfusion.

If that all seems a little clinical and free of weirdness, don't fret: per PubMed, Lower next decided to get a little freaky, taking lamb's blood and putting it into a human being in one of those beautiful, back-in-the-day moments of "you don't know unless you try." Somehow, this practice didn't catch on, and transfusions were put on the backburner until the 1800s, when researchers rolled the dice on replacing blood with milk. Luckily, that experiment only lasted, like, seven or eight years, and was soon replaced by the equally ineffectual theory that you could just pump saline into a person's veins and their body wouldn't know the difference.

Blood: thicker, among other things, than water

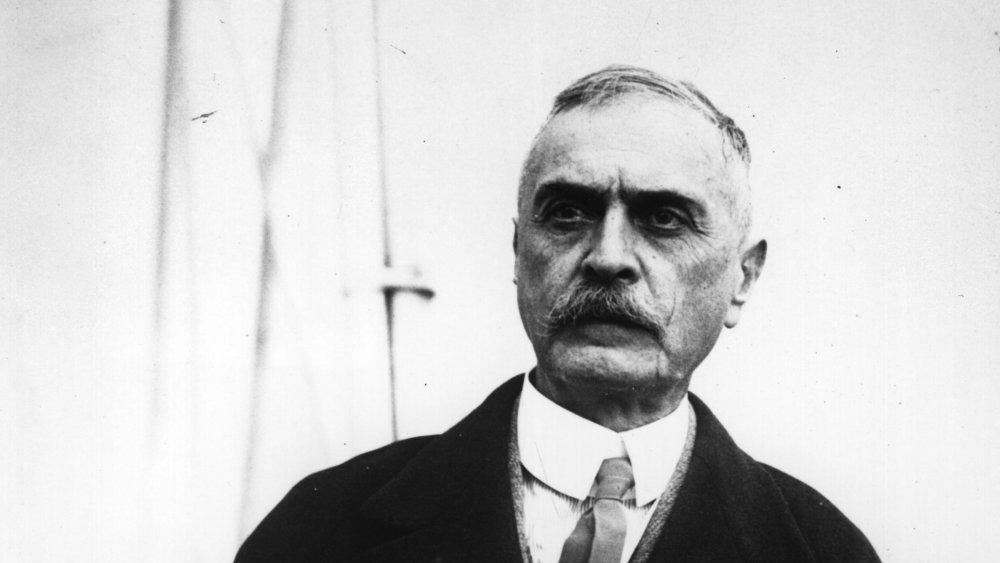

Clearly, the road to a safe method of supplying second-hand blood was a long and arduous one. It wasn't until the 20th century that a series of lightbulb moments took place. They started when Austrian physician Karl Landsteiner (pictured above) discovered the first three blood groups in 1901: A, B, and O. This revolutionized the science of not dying gruesomely, as in 1907, American professor Ludvig Hektoen suggested that matching blood types might increase the odds of transfusion recipients living longer than a couple of days. Later that year, the first cross-matched transfusion was performed, and it wasn't long before the practice started to look more like science and less like witchcraft-adjacent playtime for lunatics.

Matching blood types was a pretty enormous win for the medical community, and there's a good reason we've never doubled back on the practice. Passing the wrong brand of blood between patients is, as it turns out, about as healthy as jamming 2% into their arteries like they did 150 years ago.

Blood types: it's complicated

Here are the bare bones basics, as presented by the helpful folks at the Australian Academy of Science: everybody has a blood type, which indicates what sorts of antibodies in their blood. Antibodies are special proteins that work as your body's pit bosses, identifying problem customers like bacteria and viruses that make it into the works. A person with type A blood possesses antibodies which target specific antigens, a person with type B blood has a different set of antibodies.

These antibodies are sort of letter-of-the-law employees, and if they notice something that doesn't look right, they go on the attack lickety split. Their pedantry doesn't stop with germs, though. They'll lay the pain down on any cell that triggers their alarmingly touchy xenophobia, including any foreign blood cells that show up to the office with the wrong set of antigens attached.

A bloody mess

When this happens, donor blood is rejected by the body in a pretty dramatic way. The recipient's immune system will attack the outsider blood, exploding the proteins in the foreign blood and sending the remains into the kidneys to be separated from the rest of the gang. The human kidney, while remarkable, isn't set up to handle the sudden rush of dead blood cells that occurs when a large transfusion goes wrong. Worst case scenario, they'll shut down entirely.

With that in mind, there's almost always a blood shortage at your local hospital, with rare blood types frequently in short supply. Want to do your good deed for the day? Get in contact with a blood bank and squirt out a pint for your fellow man.