Royals Who Were Totally Bizarre People

Wealth and status don't protect you from criticism; they just make people talk quieter. Ever since the first group of people decided they needed to be led by a special person, ideally wearing a fancy hat, the human experience of monarchy has been mixed at best. It turns out that telling people that they're very, very special and that God picked them, then giving them the power of life and death over a whole country doesn't really encourage emotional stability, especially when the person involved has what we might euphemistically call a slender family tree.

Some queens have been evil, some kings have been nuts, but a far greater number of royal personages have been simply bizarre. Even allowing for the reality that being a little (or a lot) inbred and growing up in a palace aren't excellent general life skills preparation, some of the bluest blood has animated some of the most eccentric brains.

Princess Charlotte of Prussia

"Prussian" has become a byword for a kind of strait-laced, militaristic propriety. The upstart Baltic-coast kingdom that swelled into the dominant member of the German Empire doesn't really have a reputation for fun, much less wild sexual license. But in Prussia, as everywhere else, people had sex and wanted to keep the details secret. Unfortunately for certain high-ranking, erotically charged Prussians, Princess Charlotte knew what they'd been up to.

Charlotte, sister of Kaiser Wilhelm II of World War I fame, hated being pregnant and loved gossip: understandable, but not really "princessy" behavior. Even less princessy was her 1891 invitations to number of the great, the good, and the sexy in Prussian society to join her at a hunting lodge outside Berlin for hard-drinking orgies. After one of these orgies, explicit blackmail letters (some of them even illustrated) slipped through the mail slots of many of the participants, offering to remain silent about the fun for a price.

Several hints point to Charlotte as the architect of the blackmail scheme: she had arranged the gatherings, and the letters were written in apparently feminine handwriting and featured catty swipes at other female partygoers. Additionally, at about this time, Charlotte's diary somehow made its way to her brother, who read it and became so angry at its contents that he stopped his sister's income and reassigned her husband to unsexy Breslau, in Germany's far east, far away from secretly swinging Berlin.

Empress Irene of Athens

If you don't read the story of Irene of Athens very closely, it's easy to like her. An orphan with nothing but looks and luck, she caught the eye of Byzantine emperor Constantine V, who married her to his heir Leo. After Leo IV died young, Irene ruled the empire in the name of their 9-year-old son, Constantine VI, taking over as emperor (explicitly not "empress," she wore the crown and the pants) in her own name when that son too died young. Along the way, Irene considered marriage with Charlemagne and changed the church's stance on veneration of images, so for the Greek church she is Saint Irene.

A closer read makes Irene far ickier. She loved the throne much more than she loved the empire or even her own son Constantine VI, and much of her time in government was spent sabotaging those she considered a threat to her power, chief among them Constantine himself. Constantine tore out tongues, gave defeated soldiers insulting tattoos, and got himself accused of bigamy as Irene spun her web. When Constantine was good and friendless, she pounced.

In 797, Constantine VI was bounced off the throne by his own mother, who then had him blinded in the same room in which he had been born. The blinding was an old Byzantine trick intended to make someone ineligible to rule without killing them, but it didn't work: Constantine died. His mother ruled as emperor for five jittery years until she was overthrown by her own minister of finance. She died a year later in exile on Lesbos.

Prince Dipendra of Nepal

Crown Prince Dipendra of Nepal had nearly everything a person might reasonably expect: wealth, privilege, and the promise of eventually becoming king of a beautiful Himalayan country. He also had big shoes to fill, as his father Birendra had ably managed transitions toward constitutional monarchy, and his mother Aishwarya fiercely opposed his marriage to the "mere" descendant of an Indian maharajah, but these problems were probably not insurmountable. We'll never know, because according to official reports, Dipendra got drunk and high and shot eight members of his family to death on June 1, 2001, in the "Nepalese Royal Massacre."

Reportedly, during a private family gathering, Birendra smoked marijuana and "something black" on top of drinking whiskey, made some nearly incoherent calls to his girlfriend, then dressed in fatigues and armed himself. He proceeded through the palace in Kathmandu, shot his way through the billiard room and garden, and claimed the lives of his parents, siblings, and other relatives before turning the gun on himself.

The official account of the massacre is doubted by many Nepalese, who point out, among other things, that Birendra, his wife, and all three of their children died, while his brother Gyanendra, his wife, and all three of their children survived. Gyanendra became king after a perverse period in which the comatose Dipendra was technically king; he was then overthrown in 2008.

Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria-Hungary

In their last few decades in power, the Habsburgs of Austria-Hungary simply could not catch a break, as scandalous tragedies and tragic scandals rocked the imperial house. Perhaps the most shocking of these, certainly one of the most politically perilous, was the shock murder-suicide of Crown Prince Rudolf and his 17-year-old mistress, Maria Vetsera, in an Austrian hunting lodge in 1889.

Rudolf, a bird-fancier who had become liberal by the not-terribly-liberal standards of Belle Epoque Austria-Hungary, felt stifled waiting for his father, the staid and conservative Emperor Franz Josef, to die. (He lived until 1916, so Rudolf did indeed have some waiting to do.) Rudolf and most of his family disliked his wife, Stephanie of Coburg, who was considered not very pretty, very nice, or very fancy: the royal family of Belgium was not as old or grand as the Habsburgs. So Rudolf used women to distract himself from these stressors, including his ultimate and fatal companionship with Vetsera.

Whatever the final trigger for the deaths was isn't known, but Rudolf and Vetsera decided on a suicide pact. (Allegedly, she wasn't the first person he asked.) The most likely explanation is that Rudolf shot Vetsera and then himself, though some people then and now have accused Vetsera of being the killer via poison, claimed that the incident hinged on a botched abortion, or put forth various other pet theories. With Rudolf, the only son of the imperial couple, dead, leaving only a daughter, the new heir became Franz Ferdinand, whose 1914 assassination plunged Europe into war.

If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org

Queen Maria I of Portugal

Maria I of Portugal did not have a particularly easy life, as royal lives go. As heir, she couldn't marry a foreigner, so she paired off with her, um, uncle (though they do seem to have liked each other). In 1755, when Maria was a young adult, Lisbon was smashed by an earthquake and tsunami that left much of the capital in ruins, including the principal residence of the royal family. Only an outing to the countryside saved them from the fate of many of their subjects.

A fundamentally kind woman, Maria was a gentle queen who reversed some of her father's harshest policies and enjoyed a good reputation in Portugal and in its most important imperial holding, Brazil. Unfortunately, she had inherited the mental health issues that stalked her mother's family. Its initial manifestations of melancholia and religious fervor, manifested in a bedroom full of figures of saints, were tolerable in a Catholic queen, but after a series of shocks, including the deaths of loved ones and the unsettling French Revolution, Maria deteriorated. Unable to distinguish symptoms from sins, she screamed that she was already damned and suffered chaotic mood swings, forcing her to hand the government to her son.

When Napoleon's armies menaced Lisbon, she joined the rest of her family in exile in Brazil, reportedly unable to understand why she was being put on a boat and therefore screaming all the way across the Atlantic. Perhaps mercifully, she died without having to make the crossing back.

Queen Christina of Sweden

Queen Christina of Sweden is an excellent example of "weird" not necessarily meaning "bad." She became queen at the age of 6, when her father was killed during the Thirty Years' War battle of Lutzen. That left Christina, who was admittedly brilliant but also a little girl, the nominal head of a Sweden that was much bigger than it is today and embroiled in a complex war. But Christina of Sweden grew up to be a luminary. She knew at least six languages, and after coming into her full power as queen, Christina herself started the first newspaper in Sweden. She corresponded with philosophers and participated in the Peace of Westphalia, which finally ended the terrible, generations-long war.

And then, after a mere ten years as a ruling queen, she gave it all up, handing the crown to her cousin, dressing in men's clothes, and ambling south to visit Rome. In Rome, the erstwhile Lutheran converted to Catholicism, elating the pope, but then Christina decided she wasn't done being a queen and asked if she could rule Naples. Refused, she would then try for the throne of Poland, which was also denied her.

Nevertheless, Christina was still smart, opinionated, and rich, even without her own crown, and she lived out the rest of her life learning, writing, supporting the arts, and advocating for the tolerance of unpopular groups like the Jews of Rome and the Protestants of France. Among her surviving works is an autobiography, which she dedicated to God.

Princess Margaret of the United Kingdom

Princess Margaret, the sister of the late Queen Elizabeth II, was not especially similar to her famously well-behaved sibling. Margaret smoked, drank, married unwisely, had flings, and did not even come close to her sister's lengthy lifespan, dying at a relatively young 71. It's very easy to like the idea of Princess Margaret, who was apparently both very witty and shockingly glamorous: she even bought her own tiara for her wedding rather than borrowing one from her sister.

But Margaret was notoriously hedonistic. She was very aware that she was a princess, and so she did things like hit squirrels with umbrellas. She was also very interested in vice, so she did things like glue matches to her drinking glasses so she didn't have to put down her glass to light a fresh cigarette. She spent money wildly, and she was rude when she felt like it. (Nonetheless, Picasso apparently badly wanted to marry her.) Margaret certainly was a capricious character, but it's easy to imagine that her actual company would be too much for many people.

King Vajiralongkorn of Thailand

Visitors to Thailand must be aware of a particular aspect of Thai law: it is forbidden on pain of imprisonment to threaten or even speak ill of the king, the queen, the heir, or any regent in office. Fortunately, this law is only enforceable within Thailand itself; unfortunately for the Thai people, temptation must be ever-present, because Vajiralongkorn, the current king of Thailand, is a stone-cold weirdo.

Bad things first: Vajiralongkorn has clamped down on dissent within the kingdom, cycled rapidly through wives and mistresses, and by variously stripping his children of titles, has left Thailand with no clear heir. (The choices are all female, not wholly royal, or rumored to have developmental issues: people in all three of these conditions have ascended thrones before, of course, but they each present challenges within Thai society.)

Much more likably, Vajiralongkorn loves dogs. His father did too and even wrote a book about a particular favorite, but Vajiralongkorn has taken his fondness for his wet-nosed subjects to extremes that even his fellow animal lovers might find excessive. For example, he flew to Germany on a private jet with 30 poodles, and while one loves to imagine dogs having adventures, the carbon pawprint must have been appalling. Additionally, a particularly beloved poodle named Foo Foo was elevated to the rank of Air Chief Marshal in the Thai Air Force, occasionally even appearing at formal banquets. (Alas, Foo Foo died in 2015, untested in battle.) More sensibly, the king is also a patron of various charities helping animals in need.

Tsar Peter III of Russia

Tsar Peter III had the misfortune to rule for a brief period between the reigns of two far more competent, far more fondly remembered women: his aunt Empress Elizabeth and his wife Catherine the Great, who bumped him off the throne when it became clear what a disaster Peter was shaping up to be. As it turns out, Catherine had some compelling arguments.

While much of what has survived about Peter is from either Catherine's pen or those of her political allies, Peter managed to make one colossal, unquestioned error during his brief reign that alienated everyone paying attention. His aunt's government was participating in the Seven Years' War as an ally of Austria and France, and while those powers were not doing enormously well, Russia was beating Prussia into smithereens so effectively that its king considered death by suicide. Elizabeth died before the killing stroke fell, and Peter immediately made peace with Prussia, jilting his allies. He had two reasons: he greatly admired Prussia, and he wanted to invade Denmark.

Denmark could rest easy: the Russian establishment was so appalled by this reversal that they were willing to replace Peter with his intelligent German wife. Catherine took the throne, Peter died in prison, and Russian armies never ravaged Copenhagen.

Emperor Elagabalus

Lest we judge Elagabalus too harshly, remember that he became emperor of Rome when he was about 15 and lasted until he was about 19; not ages when most people are expected to be at their best. Instead of drinking Mountain Dew and listening to music his parents hated, poor Elagabalus had to pretend to run an entire empire. He failed, of course, partly because of excesses, partly because the Romans were unnerved by his queerness, and partly because he was a teenager.

Elagabalus came from a family of hereditary priests in Syria who led worship of a meteorite. When the imperial throne came vacant, his ambitious grandmother marketed him as the illegitimate son of not-great emperor Caracalla, which was good enough to get Elagabalus acclaimed as emperor. Once he was in Rome, accounts — admittedly written after his deposition and murder — describe a capricious ruler who tried to reorient Roman religion toward his family's god, Baal, and who picked good-looking yet otherwise random people to run the government.

Elagabalus took lovers of both sexes and even married a Vestal virgin, all the while ostensibly presiding over bizarre banquets that served dishes like flamingo brains and killing too many well-connected generals. This combination of sexual license and disregard for convention doomed his reign, and Elagabalus was assassinated in 222.

King George III of the United Kingdom

Poor George III would almost certainly have been happier as anything other than a king. His reputation largely rests on his having been king during the American Revolutionary War and having then gone "mad," which while true, obscures the more mundane ways in which the third of the "German Georges" was an odd man.

Touchingly, being a good king was very important to the shy and unconfident George. He came to the throne in 1760, in time to be theoretically in charge when Britain overwhelmed France in the Seven Years' War. In order to choose a wife efficiently, he had an adviser draw up a summary of Protestant German princesses about the right age. While clearly not a natural romantic, he did do well in choosing Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, the loose inspiration for Queen Charlotte of "Bridgerton" fame.

As the king aged, his odd personality grew more apparent and less easy to excuse on youth and inexperience. He rambled, talking for hours on topics that apparently interested him but were not necessarily sparkling drawing-room conversation, and he tried to personally exhort farmers to increase their output. He also attempted to tightly control the lives of his children, probably acting out of misguided love. The boys could and did wriggle out of this too-tight hug, but the girls lived profoundly claustrophobic existences bounded by their parents' anxieties. George's initial, relatively brief mental collapse in 1788 was followed by a permanent detachment from reality in 1811; he died after nine rarely lucid years in 1820.

If you or someone you know needs help with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

Caroline of Anspach, Queen of the United Kingdom

Caroline of Ansbach was exactly what you might want in a queen. Pretty and demonstrably intelligent, she was able to manage her intellectually lightweight husband, George II, who loved her for it. Caroline understood her husband so well that she chose manageable mistresses for him who wouldn't cause more trouble than necessary. Outside the palace, she encouraged smallpox vaccination in Britain — having her own brood of princes and princesses immunized — and also distinguished herself as a patroness of the arts. Caroline was even trusted to run the government while the king was away running his other possession, Hanover. This Enlightenment queen could surely bring nothing but joy and progress to the court in London.

However, Caroline absolutely despised her eldest son, as did her husband, who had himself been hated by his own father. In fairness, Frederick, Prince of Wales, was not an ideal prince, preferring to run around with a bad crowd and gamble, but since he had been left to grow up alone in Hanover while his parents hopped over to London to take their crowns, it might be understandable that he didn't much care what they thought. Caroline and George brought Frederick's sisters to Britain before they brought him, and when he arrived they literally brought him in through the back door. Furthermore, they didn't give him an allowance.

As time went on, the situation got so bad that Caroline tried to have the British crown skip Frederick and go to his brother, and the royal couple tried to micromanage the birth of Frederick's first son in 1737. The rift was unmended when Caroline died later that year.

King Frederick William I of Prussia

If King Frederick William I of Prussia had been a kinder man, he would still have been widely remembered as an eccentric. Admittedly, he was an extremely competent administrator, repopulating areas that had been battered by plague and instituting financial reforms that made the kingdom comfortably solvent. His real baby was his army, which he built into a large and potent fighting force using a revamped system of recruitment within and outside his domain.

Famously, Frederick William liked tall soldiers (as many people do, one might say with a wink). He formed a special Prussian regiment of grenadiers, all above about 6 feet 2 inches in height, with taller men receiving more pay. These men might be bought from their parents as promisingly lanky children, transferred from other armies by leaders interested in pleasing the Prussian king, or simply abducted. Showing a mixed understanding of science, Frederick William tried to stretch some of the men on a special rack, and paired some off with unusually tall women in hopes of creating gargantuan offspring.

Frederick William was astonishingly cruel to his son Frederick, an artistic and cultured (and gay) young man. When Frederick's attempt to escape his father's physical and mental abuse failed, the prince was forced to watch the execution of the friend who had tried to help him, and feared he would also go under the blade. Frederick had the last laugh, though: he was a better king than his father and is remembered as Frederick the Great.

Elisabeth Charlotte of the Palatinate, Duchess of Orleans

Elisabeth Charlotte of the Palatinate is a figure whose eccentricities charm rather than repel. In the vapid, frivolous court of Versailles, Elisabeth Charlotte — Liselotte to her friends, "Madame" to everyone else — remained just as she was: plainspoken, free of vanity, and very, very German.

Liselotte was from the Palatinate, a German princely state in the Rhineland, near France's eastern edge, which was important because its ruler helped elect the Holy Roman Emperor. This made her fancy enough to marry Louis XIV's brother Philippe, Duke of Orleans. Philippe's main loves were men and gambling, which made him fun at parties but a poor personal match for Liselotte, though they did manage to produce two children, if apparently only through determination. For her part, Liselotte hated the fussiness of the court and dissected it in many witty letters to friends and relatives back in Germany. She knew they were read by spies and enjoyed describing embarrassing events like chamber pot mishaps to discomfit the king's monitors.

Elisabeth Charlotte never lost her Germanness, preferring German food (including beer) when she could get it and eating enough to become portly in later life. She hunted, rode horses, and loved a good fart joke: not very ladylike by Versailles standards, but these traits earned her the king's friendship. Her life at the court was difficult, but her wit and uniqueness, along with the fact that she simply outlived many of her rivals, left her a legacy as one of the few truly likeable figures from the court of the Sun King.

King Charles XIV John of Sweden and Norway

Few people have had more dramatic changes in fate, along with the instincts to ride the changes to the top, than the man who at the end of his life was King Charles XIV John of Sweden and Norway. At the beginning of his life, he had been Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte, a lawyer's son from southwestern France. He joined the French army as a young man and sided with the Revolution when it arose, leading troops with success and discipline in the resulting wars. He had a complicated relationship with Napoleon, but Charles' oath of allegiance after Napoleon declared himself emperor was enough to get him roles in occupation governments in Germany.

And then, in 1810, someone asked Jean-Baptiste if he would like to be king of Sweden. Charles XIII was childless and not very healthy, so the job would be open sooner rather than later. The Swedes had been impressed with his administration in Germany and civil treatment of Swedish POWs, plus a connection to France was probably a decent idea if Napoleon was going to continue rampaging across the continent.

The former revolutionary accepted and excelled, steering Sweden calmly through the rest of the Napoleonic wars and taking Norway from Denmark as easily as if it were lunch money. Despite never really learning Swedish, he reigned more-or-less successfully until his death in 1844, and his descendants are the current royal family of Sweden. The story that he had a tattoo on his chest reading "Death to Kings," a souvenir from his old revolutionary days, is almost certainly not true, but a surviving letter from 1797 reads in part: "...I want to fight all royalists to my death."

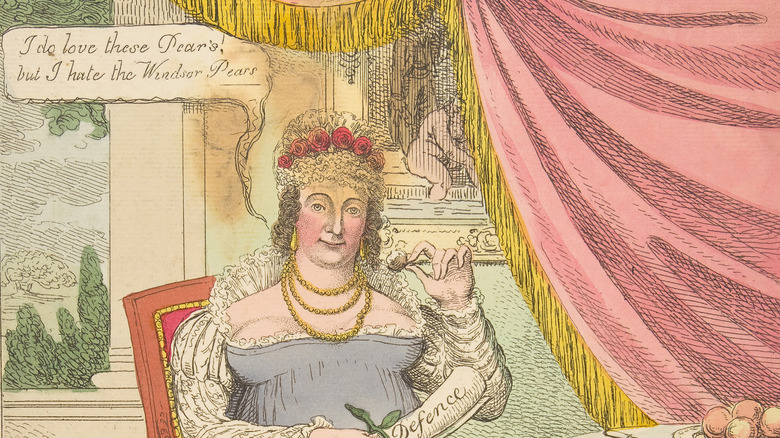

Caroline of Brunswick, Queen of the United Kingdom

Even relatively sympathetic accounts of Caroline of Brunswick read like insults. She was to be the wife of the future George IV of the United Kingdom, but someone somewhere didn't carry out their due diligence. The only thing worse than her manners was her hygiene: on their first meeting, the poleaxed Prince of Wales reportedly needed a drink. After their one recorded night together produced an heir (female, but would do in a pinch), the Prince informed Caroline that her bedroom duties would no longer be required.

So Caroline amused herself as she wished, which involved collecting erotic clockwork, dancing suggestively, and eventually traveling around Italy bare-breasted and having affairs. When King George III died in 1820 and it was time for George IV to be crowned, he tried to bribe her to remain out of Britain. When she returned anyway, he attempted to exclude Caroline from the queenship she might reasonably expect to enjoy, due to her still being technically married to the king.

George tried to push a bill divorcing Caroline through parliament, but gave up when it became clear it would fail. Meanwhile, the British public, already unhappy with the government George had headed during his final illness, swung behind Caroline and produced a wealth of cartoons and satirical pamphlets. It didn't help: she tried to physically force her way into the coronation, failed, and died three weeks later.

Empress Elisabeth of Austria-Hungary

The Wittelsbach royal line of Bavaria was always a little off. So when an exceptionally pretty princess from that family, Elisabeth, was chosen to marry the young Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary, her unhappiness seemed inevitable in retrospect. Despite the very real love both her husband and the Austro-Hungarian populace bore for Elisabeth, affectionately called Sissi, she was seldom happy and died before her time in a senseless assassination.

Sissi had an eating disorder, though this wasn't fully understood at the time, retaining a sub-20-inch waist into late middle age despite childbirth and rich Austrian cuisine. She was obsessed with the preservation of her own beauty, both on her actual face and in the public record: she allowed no photographs of her to be taken after she was 30. Intelligent and restless, she was bored senseless by the stuffy Habsburg court and escaped when she could to Hungary, which she liked better. (A measure of her intelligence is that she learned the famously challenging Hungarian language.)

After her son Crown Prince Rudolf's death in a shocking murder-suicide, Elisabeth lost what little ability she had ever had to sit still. She moved to Greece, then back to Vienna, but continued anxiously travelling, trying to outrun her depression. In 1898, as she visited Lake Geneva, an anarchist stabbed Empress Elisabeth in the chest: his intended target, a French princeling, had changed his plans, but an empress would do. Sissi was so surprised she did not immediately realize she had been injured, walked a hundred yards onto a ferry to France, then collapsed and died.

If you need help with an eating disorder, or know someone who does, help is available. Visit the National Eating Disorders Association website or contact NEDA's Live Helpline at 1-800-931-2237. You can also receive 24/7 Crisis Support via text (send NEDA to 741-741).

Prince Felix Yusupov

Prince Felix Yusupov must have been awfully fun, if you could keep up with him. As a child, he used to pretend to be the Ottoman sultan — costumed in his mother's baubles — and claimed to hear ghosts. As an adult, Yusupov inherited a colossal fortune, had a brief career as a drag artist, and then married Irina Alexandrova, the tsar's niece and one of the most glamorous women at the Russian court.

Yusupov was also one of the key figures in the 1916 plot to kill Rasputin: it is from his memoirs that we have the famous story of Rasputin gulping down cyanide-laced wine like it was mere wine-laced wine and then asking for more. Yusupov and company eventually did kill him, though. For this he was fined and exiled to the very edge of Russia, putting him and his wife, Irina, in an excellent position to escape the revolution when it came the next year.

Yusupov never pretended not to have killed Rasputin (in fact, he almost certainly embellished his account), nor did he especially hide his queer-coded flamboyance, but when a film insulted his wife, he came at Hollywood fists flying. A 1933 biopic called "Rasputin and the Empress" includes Rasputin's rape of a very thinly veiled version of Yusupov's wife. Rasputin never met the real Irina, and the furious Yusupovs won a doozy of a court case, winning cash and edits. This is why films now almost all have a disclaimer about being a work of fiction. Yusupov went on to continue bragging about having killed Rasputin until his death in 1967.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).