11 Worst Things That Happened During Market Crashes

"Sell in May, go away." "Buy the dip." "People will always drink Coke." There are a million little conventional-wisdom tidbits of stock advice floating around, all of them hoping to convince investors that the markets are something they can learn and predict rather than the world's fanciest roulette wheel. A more honest rule of thumb would go something like "events happen, people try to make money, and every couple of decades it all comes crashing down and makes a huge mess."

It's easy to jeer at traders, but of course the stock market is also connected to the real economy, and when the seemingly imaginary numbers start blinking red and tanking, they can take real people's money (and futures) with them. Investment crashes have been a feature of economic crises ever since people started betting on the future, and through it all, one fact has been proven right more than anything else: From tulips to memecoins, an asset is only worth what you can sell it for ... and sometimes that's nothing.

The first one sparked lasting misinformation (about flowers)

Tulips are so strongly associated with the Netherlands that it's surprising to learn they're not native to the watery little kingdom. The tulip's way-back home is the mountains of central Asia, from there coming to Byzantium sometime during the Middle Ages and becoming one of the many things to delight the Ottomans as they consumed the last of the Byzantine world. So when the Dutch became rich after becoming independent from Spain (TL;DR on that is royal marriages and Protestantism), they started buying fancy things from faraway places like Turkey.

The conventional wisdom is that, drunk off both the beauty of the tulip and their own ability to create futures markets, the Dutch population briefly went absolutely nuts buying and selling tulips, creating a speculative bubble now known as Tulip Mania. Everyone was in on it, putting everything they had into tulips, hoping especially to buy a bulb that would produce a prized striped blossom. When this runaway speculation became untenable, the bubble popped, and everyone lost their little Dutch shirts.

Unfortunately for those of us who love a good yarn, this story is exaggerated. There was some wild and wacky speculation on tulips, but the collapse in prices was not the ruinous event it's been made out to be. Some of the most overblown examples of people betting it all on bulbs in fact come from Calvinist propaganda intended to make people calm down and think about Hell again. In fact, no record survives of even one flower trader going bankrupt in all of the Netherlands.

A single man nearly bankrupted France

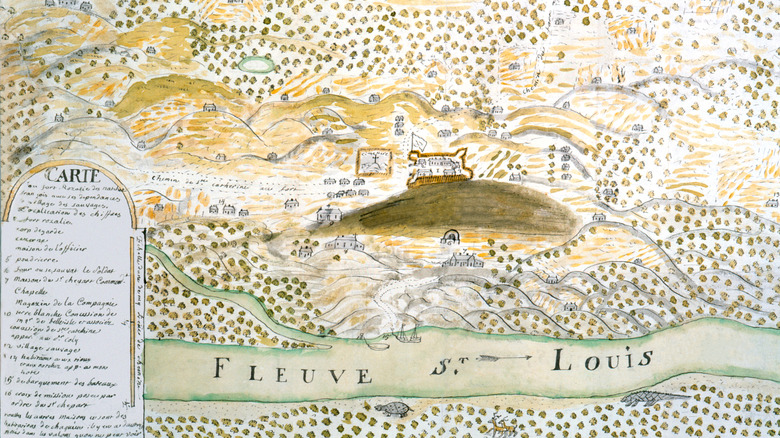

French king Louis XIV loved mistresses, palaces, and especially wars; unfortunately, these are all expensive, and when the king died in 1715, France was more or less out of money. (Live fast, die old, leave an empty treasury.) A Scottish huckster named John Law sidled up to the Duke of Orleans, who was running the government for underage Louis XV and after whom New Orleans was about to be named, with a plan.

Over the next two years, Law set up a bank to start printing and distributing paper money and established a company to monopolize trade with French Louisiana for the government. Soon, this company controlled all exterior French trade and had taken on France's national debt. Now, you may notice that this essentially means that within three years, the entire economic management of a major colonial power had been signed over to Some Dude. And when said dude mishandled the situation by overvaluing stock shares and printing too many paper bills, the whole shebang collapsed in a puff of hyperinflation and devalued assets.

The French government had to reimburse angry investors to calm the storm, defeating the whole "fix the national budget" rationale. Law fled France, dying poor in Venice a few years later.

The United States had to pass its first bankruptcy law in 1800

Owing money is seldom particularly fun, but it used to be worse than it is today. Debtors without the means to repay could be imprisoned or have their ears cut off, and early bankruptcy law wasn't much better: The 1705 Statute of Anne in the United Kingdom prescribed death for fraudulent bankruptcy. As the financial world grew more complex, though, it was increasingly clear that in order to encourage the speculation that drove growth in an era of innovation and colonization, people needed to occasionally be allowed to wiggle their way out from under a pile of debt.

At independence, the United States had no bankruptcy law, but shaky conditions in the fledgling republic meant financial panics. One hit in 1792 and a second in 1796, the latter fueled by land speculation and bank runs in a Britain jittery about the ongoing war with France. Businesses went bust in the major cities of the East Coast, and important revolutionary figures and financiers went to debtor's prison or had to beat feet to avoid it. Faced with the unattractive prospect of punishing the people who had paid for the revolution, the United States passed its first federal bankruptcy legislation in 1800. (Otherwise, states could legislate independently if they wished.) This federal law was only in effect until 1803, with temporary legislation popping up again after subsequent crises; permanent bankruptcy legislation only arrived in 1898.

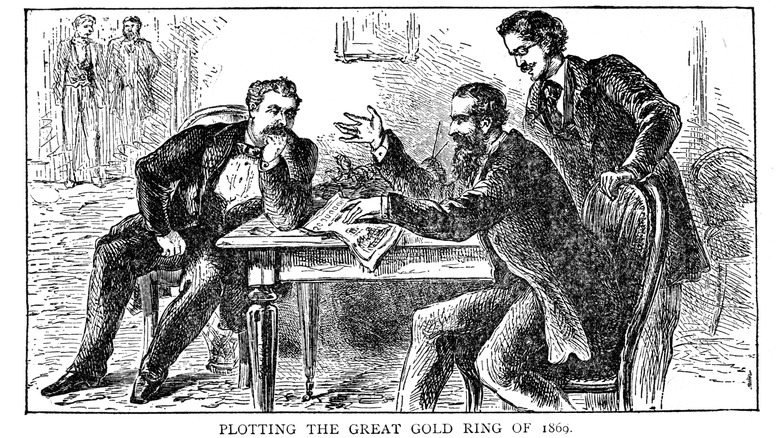

A scam to fix gold prices nearly derailed Reconstruction

An important aspect in the success of many financial scams is that many people do not understand complex money movements and grow bored when someone tries to explain them. The Black Friday of 1869 is one of these scrambles. Boiled way, way down, two already wealthy men, Jay Gould and James Fisk, thought they could enrich themselves even further by manipulating the price of gold on American markets. The U.S. was selling gold in regular tranches to pay off Civil War debts, and if gold went up, greenbacks would go down and make American exports more attractive. Gould and Fisk would benefit both from increased use of their railroads for exports and from the spike in value of the gold they already held.

Gould and Fisk had a mole in the Treasury alerting them to government plans, but they got greedy. When their manipulation became apparent, President Ulysses S. Grant released a then-considerable $4 million in gold reserves to drive the price down and foil the scheme. The plan collapsed, along with markets. Gould and Fisk got away without any real consequences, though Fisk was murdered over a woman three years later.

The months of financial chaos that followed were the last thing the U.S. needed so soon after the close of the Civil War. Reconstruction was still in effect, with most of the former Confederacy still occupied by Federal troops. A second financial panic in 1873 (also under Grant) sapped the public appetite for Reconstruction, and the project ended in 1877.

The world economy almost completely collapsed

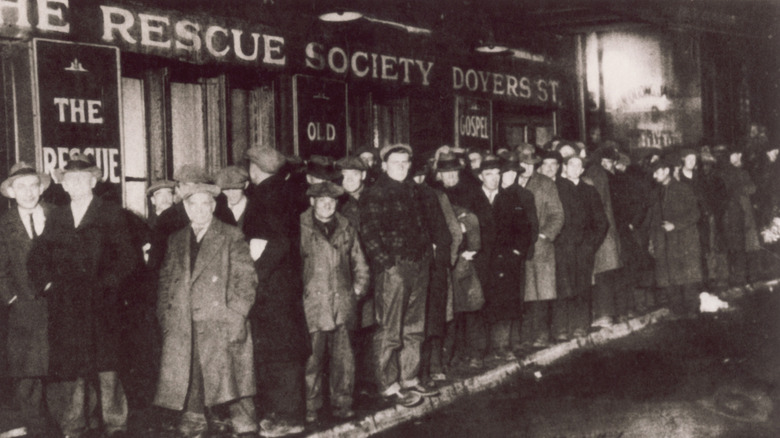

The Roaring 1920s' image of wealth, exuberance, and gyrating flappers swilling champagne has endured even into the 2020s, a much less ebullient decade for most of us trying to get through it. The music always stops, though, and the giddy jazz of the '20s ended with a grim thud on October 24, 1929. "Black Thursday" was the beginning of the crash of all crashes (so far), the big stock market meltdown that was one of the largest continuing factors in the Great Depression.

The wealth of the 1920s didn't have a completely solid basis in productivity booms, and so the sky-high prices of many stocks in 1929 were underpinned largely by optimism, which is not a durable economic good. Small selloffs in October 1929 snowballed into each other, compounded by the fact that many stocks had been purchased on margins, an optimistic technique involving investing with borrowed money on the assumption the asset will rise enough (and quickly enough) for profits to cover the vig. The analog technology of the time couldn't keep up with the growing avalanche of people hoping to sell their swooning, then fainting, then collapsing stocks. Ultimately, as confusion mounted, police were sent to Wall Street to guard against disorder.

The chaos calmed down a little on Friday, but the next Monday and Tuesday saw further punishing declines in stock indices. Economist and historians chicken-and-egg the 1929 crash and the subsequent depression, with some arguing the crash did not cause the depression but happened because the depression was about to unfold. Regardless, the crash has historically been seen as the first major sign of the long and cataclysmic Great Depression.

The world went to war

Some of the countries hit hardest by the Great Depression were in Central Europe. As part of the peace treaties ending World War I, Germany had been hit with punishing war reparations it was just managing to stay on top with help from American loans, but these dried up (and were even called into repayment) when the crisis hit the United States. A bank failure in Austria in 1931 pulled down a number of banks in surrounding countries with it, ultimately scrambling Germany's entire financial system. Impoverished and resentful, German voters elected Adolf Hitler in 1933.

A few years later, the United States' own recovery tanked. The recession of 1937-38 was a serious downturn, with GDP dropping 10% and unemployment bouncing back up to a nauseating 20%. The causes seem to have been a mixture of tax increases (including those linked to the new Social Security program) and government policies requiring banks to hold higher reserves; in short, the U.S. was acting like it had fully recovered from the Great Depression when it had not yet. Government policy changes helped the economy turn around, but the real jolt was a massive stimulus in the form of the defense buildup before World War II and the huge industrial production the war required.

Bankers had to invent circuit breakers to stop total collapse

The first eight months of 1987 were great for stocks, and people who sold in August walked away with very attractive gains for the year to date. The rest of the investing public, however, was in for an unpleasant fall. Disappointing figures for the U.S. trade deficit combined with other scraps of pessimistic news led to a 4.6% drop in the Dow Jones on Friday, October 16. On the morning of Monday, October 19, markets in Asia and the Pacific plunged, setting U.S. markets up to tank at the opening. Tank they did, plummeting over 20% on the day. (Poor little New Zealand had it much worse, with their markets falling a whopping 60%.)

The crash of 1987 led to a number of reforms in the markets, and most of the losses were recovered fairly quickly. The most prominent of the new rules were the "circuit breakers," still in effect today, which automatically stop trading for a period of time if and when markets drop a certain amount. These can apply to individual stocks, but the ones that usually cause comment if they're triggered (or seem likely to be) are the market-wide stops. A 15-minute pause in trading occurs if the S&P index tanks below 7% from the previous day; it happens again if the index keeps falling past 13%. At 20%, trading is done for the day to prevent (or, you know, at least postpone) a crash resulting from panic selling.

Early web commerce companies collapsed en masse

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, people were very excited about the internet, though they did not entirely know what to do about it. There were plenty of ideas kicking around, though, and suddenly anyone who could put together a website could ride the cresting wave of the new internet economy — or at least appear to. Because the whole idea of internet commerce was so new, people didn't really know how to evaluate if a business plan was good or not, and investors poured money into businesses that "sounded cool" but didn't really have a way to make actual profits. Plus, people were still a little creeped out about giving their banking information to "some website."

Without profits, it is hard to keep a business afloat, as entrepreneurs and investors began learning when the bubble burst in 2001. An interest rate increase spooked investors, and as they began to sell, the tech-weighted Nasdaq began to drop like Wile. E Coyote, losing nearly 4,000 points between the March 2000 peak and the October 2002 trough. Many, many "dot coms" failed, including pre-Google search engines, semi-licit music streaming services, ahead-of-its-time pet-supply service pets.com, and a weird "web currency" called "beenz."

2% of Icelanders banged pots together outside their parliament

In 2007-08, the global financial markets came very, very close to collapse. American banks had been allowed to become too big and were encouraged to extend credit too freely, and as the failures and strains rolled through the American economy and spilled out across the wider world, the Great Recession began. The Great Recession was the worst financial disaster since the Great Depression, and while most parts of the world would be affected to some degree, a particularly badly-hit country was cold and lovely Iceland.

Iceland had tried to generate more wealth by growing its banks, franchising them into other countries and hoping to emerge as a financial power. Unfortunately, when the crisis hit, these banks were operating in foreign currencies Iceland itself could not influence or supply emergency funds in, and so Iceland's banks failed over the course of a single appalling week. This annoyed the Icelanders, and from October 2008 regular protests outside government buildings called for the ouster of the government, often banging pots and pans to make a racket.

The biggest crowds reached six to seven thousand people, possibly representing over 2% of Iceland's population of about 320,000. (25% of Icelanders may have participated at some point.) The protests worked: in January and February 2009, the Icelandic government and key financial regulators all resigned.

The eurozone almost got smaller

The 2008 crisis strained public budgets within the eurozone, especially in a group of countries that become known derisively as the PIIGS (Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, and Spain; Cyprus was also in trouble, but apparently not worth wrecking the acronym for). Of these troubled countries, Greece grabbed the most headlines, as low tax receipts, stock market dips, and ever-higher sovereign debt burdens pushed the country toward calamity. Austerity measures imposed by the government triggered strikes and unrest, and people began to float the idea of Greece simply leaving the eurozone altogether.

By this logic, a restored drachma would replace the euro in Greece and fall in value pretty quickly, making Greek holidays and exports attractive for people whose euros would suddenly go a lot further. This would, after some unpleasant adjustments, bring investment into Greece and allow it to recover. The flipside is a potential crash in living standards, which is not usually something that stabilizes a political situation, and a theoretical-but-feared subsequent drift away from European and NATO alliances.

Eventually, Greece somewhat recovered with help from fellow euro countries, notably Germany. This was uncomfortable for Greece, whose politicians have argued that Germany already owes Greece financial reparations for the Nazi occupation during World War II, but so far the Hellenic Republic has managed to stay in the eurozone.

Oil futures far outstripped current prices

Oil companies are not perhaps the most sympathetic victim of the early-COVID market uncertainty, but the sudden drop in demand for oil brought about by the near-total halt to travel in much of the world did put them in an awkward spot. Oil extraction can't be turned off immediately, and major suppliers Russia and Saudi Arabia bickered about how much and how long to cut oil supplies in the face of the crisis, and so for once the world was starting to find itself with too much oil on hand.

This whole situation let to a freefall in oil prices, including one of the strangest statistics you'll ever see: For a period of time in April 2020, West Texas Intermediate, a particular type of oil (guess where it's from and how high-quality it is), was trading at negative prices. With storage filling up, the suddenly-limited market oversupplied, and uncertainty continuing to build, you could theoretically have gone to an oil supplier and had them give you a barrel of oil and $37 for your trouble. Eventually, of course, people began to use oil again and the situation righted itself, but the negative price of a benchmark-type oil underscored just how weird the world briefly became.