18 Most Bizarre Details Everyone Ignores About WWII

There's no denying that World War II was a massively complicated affair. Sure, you could distill it down to the face-off between the Axis powers (led by Germany, Italy, and Japan) and Allied forces (headed by the Big Three of Britain, the Soviet Union, and the United States), but that belies the intricacy of a worldwide conflict that involved staggering numbers. An estimated 70 million people served in various military forces, with between 15 to 17 million of them dying in combat. Many more civilians died over the course of the global conflict (some sources estimate civilian deaths at a bone-chilling 45 million). Those numbers alone give you a sense of the scale of the war, which involved all manner of troop movements, invasions, espionage campaigns, weapons development programs, and more.

In short, there was a lot going on during the Second World War. While some of the activities are to be expected, others remain pretty odd to this day. People on both sides often seemed willing to try just about anything that could have given them an advantage, including some seriously odd misinformation campaigns and, for the Allies, repeated attempts to get small animals to deliver bombs to the enemy.

During the many campaigns of the war, unnerving coincidences, strange turns of fate, and unusually determined combatants sometimes came together to spin unusually arresting tales. While your history textbook may have forgotten to mention many of these bizarre details, these WWII twists are well worth remembering.

Britain put out a misdirection campaign based on carrots

You may have heard about the notion that eating plenty of carrots is good for your eyesight. That's not entirely wrong, as carrots do contain plenty of vitamin A, which plays a key role in the maintenance of our eyes' photoreceptors and the production of rhodopsin, a pigment that assists your eyes in low levels of light. But it hardly replaces a trip to the optometrist, and a bag of baby carrots definitely isn't going to correct your astigmatism.

But in WWII, Britain engaged in a misinformation campaign that hinged on that very notion of carrots leading to superhuman night vision. Britain's Air Ministry did so with the hopes that eavesdropping Germans would fall for it, but the whole thing was a ploy to cover up the real reason British forces were knocking down German planes during nighttime air raids: radar. But it wouldn't do for the Nazis to know about any advantage that a bomb-battered Britain had to defend itself.

Instead, the Air Ministry issued press releases saying that pilots could spot German planes at night because they really, really loved their root vegetables. It probably didn't hurt that at-home Britons, struck by food rationing and urged to grow their own produce, then had an extra motivation to enjoy their carrots. It's not clear that any Germans really fell for it, but the campaign certainly played into the myth of carrots giving you superhuman vision.

Chemical warfare led to the development of chemotherapy

In a very odd way, we have chemical weapons to thank for chemotherapy. Its role in WWII centered on the busy Italian port city of Bari, which had been taken by Allied forces in September 1943. On December 2, German planes attacked and damaged a munitions-carrying ship so badly that it leaked flaming fuel into the harbor and killed an estimated 1,000 service members.

Soon after, U.S. Lieutenant Colonel Stewart Francis Alexander, a doctor who had studied chemical weapons, was called to Bari to address an odd wave of illnesses. Where medical staff would have expected symptoms of shock — some sailors had been forced to swim through floating oil slicks and were seriously burned — patients were oddly calm, even comfortable. Some complained of problems with their eyes and experienced odd swelling and blisters, while those who seemed healthy sometimes suddenly died. Alexander determined that sailors who had gone into the water had come into contact with a toxic chemical agent similar to mustard gas.

Bloodwork showed that the affected people had white blood cell counts that had dropped off soon after the attack. While the death and suffering in Bari were intense, later research on lab animals indicated that this could be a medically useful factor for cancer patients. In fact, nitrogen mustard-derived agents had been used to treat cancer just a year earlier, but the data collected in Bari and the work of researchers proved a major advance that led to chemotherapy.

Some wunderwaffe were seriously off-the-wall

During much of the war, Nazi engineers, scientists, and other researchers were tasked with developing new weapons meant not only to cause destruction, but to instill a sense of awe and dread. Known as "wunderwaffe " (wonder weapons), they included highly destructive munitions like the jet-powered V1 bombs or the even larger V2 rockets. But then the wunderwaffe got weird.

This list of odd weapons includes the P. 1000 Ratte tank, which never got past the design stage. The reason? It would have topped out at more than 1,000 tons. Hitler reportedly took quite a shine to it, but other officials nixed the idea as impractical. Another weapon, similar to the Ratte tank in its Looney Tunes-style audacity, was a curved-barrel rifle attachment known as the Krummlauf, meant to allow soldiers to shoot over and around barriers. When U.S. forces tested seized Krummlauf attachments, they found that bullets often fragmented and the attachment seriously reduced the working life of the gun.

But perhaps the oddest wunderwaffe of all was the notorious "sun gun." The basic idea was a giant orbital parabolic mirror that would focus the sun's rays into a beam and blast a target on the ground. No one seems to have hammered out production details, much less how it was meant to get into space or be maintained. If this sounds almost reasonable, remember that the first-ever artificial satellite was Sputnik I, launched by the Soviet Union in 1957, over a decade after the war ended.

Top Nazi officials had vocal anti-Nazi relatives

Embarrassing relatives can be awful, but in the case of the Nazis, they had it coming. One, Albert Göring, was the brother of Hermann Göring. When Hermann was wounded in the failed 1923 coup known as the Beer Hall Putsch, the brothers became estranged; Albert later said this was due to Hermann's increasingly fanatical politics. As WWII loomed, the brothers reconnected, but Albert actively helped Jewish people escape. By 1944, an order to execute him was issued and Albert — warned one final time by Hermann — went into hiding. Albert was later imprisoned by the Allies, but a Nuremberg interrogator and members of the Czech resistance confirmed that he had been working against the Nazis.

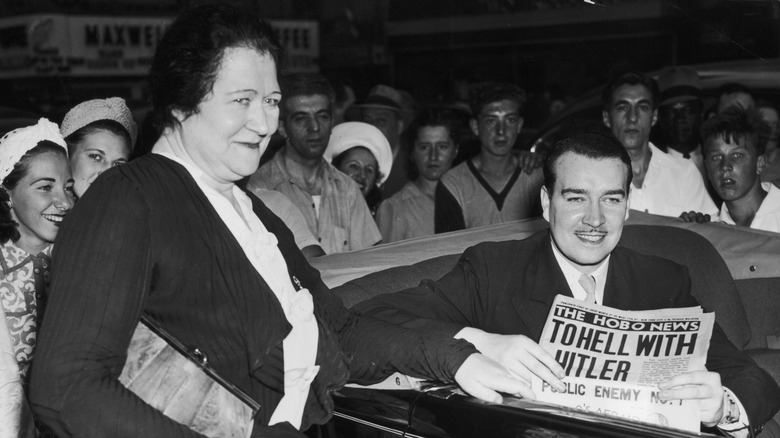

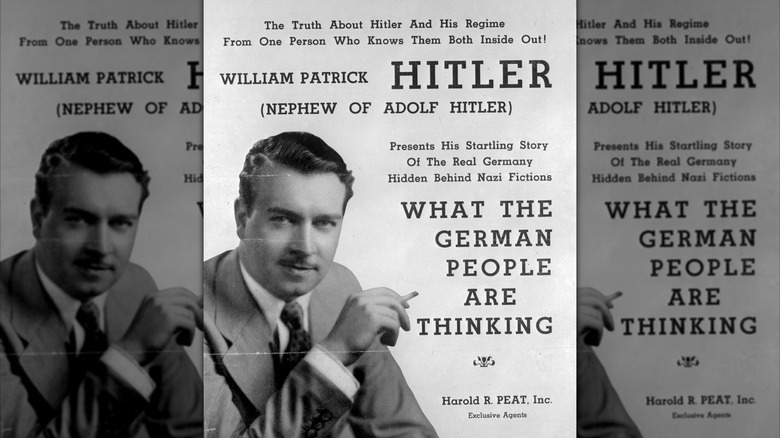

Hitler himself had an Irish half-nephew, William Patrick Hitler. William was born to Alois Hitler, Adolf's half-brother, and Bridget Dowling in 1911. Alois returned to Germany in 1914 for work but, with WWI, Alois simply stopped writing and Bridget assumed he had died. In fact, Alois had become a successful restaurateur and started another family.

Despite the awkwardness, William visited his father in Germany and moved there in the 1930s. There, he enjoyed his powerful connections until they proved inconvenient, at which point he became a vocal critic of his uncle (who hated him right back). Eventually, Bridget and William moved to the U.S., where William gave lectures about his terrible uncle and even joined the U.S. Navy in March 1944. After the war, he changed his name and lived on Long Island until his death in 1987.

The Allies really tried to make animal-based bombs work

In Britain, one odd weapons venture in 1941 centered on dead rats. An agent would go into German-held territory and place a rat containing an explosive charge next to coal meant for boilers in strategic places. The hope was that a grossed-out worker would simply toss the rat into the boiler; cue explosion. Only, Germans found the first bomb rats without any explosion occurring. However, German forces wasted time studying the rats and searching for any extras in their coal piles, despite Britain not sending any more incendiary rodents.

The next year, surgeon Lytle S. Adams proposed strapping incendiary timebombs to bats, after being inspired by a visit to Carlsbad Caverns in New Mexico. Dropped over a Japanese city, the bats would roost in mostly wooden structures. Upon detonation, a destructive firestorm would ensue. Army officials snagged some Carlsbad bats for a 1943 test, which worked so well that the bats set many buildings at nearby Carlsbad airbase aflame. The plan never progressed, however, as bats were considered less reliable than humans.

In 1943, psychologist B.F. Skinner designed a pigeon-guided missile. Specifically, he crafted a missile nose cone with space for three pigeons, each facing a small screen. The pigeons were to be trained to peck when they saw a target on the screen, which would aid in navigation. Unfortunately, this also meant that the birds would perish upon impact. Fortunately — at least for pigeon-kind — military officials turned down the prototype.

German officials were very into amphetamines

War happens to make a lot of once-small issues very important, from keeping supply lines clear to cheering up a bedraggled civilian populace. But what if everyone's really sleepy? During WWII, Germany's answer to this problem wasn't mandated naptime. Instead, it was sometimes amphetamines.

Prior to the 1940 takeover of France, German troops were given meth in the form of the pill Pervitin, which could keep them awake and moving for days at a time. Similar pills were distributed to troops elsewhere in the European theatre of war. However, beware tales of panzerschokolade, which claim that soldiers in tank companies were given chocolates laced with methamphetamine. There's no truth to that, despite doctored images circling the internet claiming to show chocolate bar wrappers touting the Pervitin inside. But Pervitin was distributed in other forms, and some top Nazi officials were also fond of its intensely energetic effects. Hitler himself may not have taken Pervitin, but his personal physician, Dr. Theodor Morell, seemed happy to give the Führer just about everything else narcotic, from other forms of amphetamines to oxycodone.

It's all the more odd when you consider how, outwardly at least, Nazi Germany took a hardline stance against drugs. The regime's attempts to bring Germany back to its imagined former glory left no room for what it deemed immoral and weakening drug use. But Pervitin and similar drugs were lauded, bringing a temporary, manic energy back to what was ultimately a seriously unstable society.

An American pilot reportedly flew his fighter plane under the Eiffel Tower

When it comes to thrilling war stories, few things grab attention more than a thrilling aerial dogfight. But American pilot Bill Overstreet might have an advantage, as he not only reportedly chased a German plane through Paris, but managed a daring spin through the bottom struts of the Eiffel Tower. It all happened in 1944, when Overstreet flew a fighter escorting bombers through Nazi-held France. During the mission, the group was attacked by German planes, and Overstreet peeled away to follow one at seriously low altitudes through the heart of Paris.

The Luftwaffe pilot appears to have led Overstreet so low in the hopes that anti-aircraft guns would get the American off his tail, but with no such luck. Even when the enemy pilot went beneath the Eiffel Tower, Overstreet followed and managed to hit the German craft (though he said it wasn't clear if the pilot was injured and he never saw the plane definitively go down).

City residents were reportedly quite thrilled by the spectacle of a U.S. plane chasing down Nazis both in the air and frightening those on the ground, to the point where German occupiers faced a three-day resistance in the aftermath. However, Overstreet was weirdly nonchalant about the whole thing, later saying it was "no big deal. There's actually more space under the tower than you think. Of course, I didn't know that until I did it," he admitted (via The Independent).

Operation Cornflakes tried to make Germans sad by mail

World War II was rife with propaganda meant to dishearten both troops and civilians. Tokyo Rose was the moniker given to a group of English-speaking women whose radio broadcasts intended to demoralize U.S. troops, while "Lord Haw Haw" did much the same over in Europe. Both sides also took the tack of dropping leaflets to get the other to capitulate or at least feel bad. Then, there was Operation Cornflakes.

It wasn't really linked to food, but Operation Cornflakes might have had some crying into their morning bowl of cereal. The idea generated by the Office of Strategic Services involved bombing a German mail train and dropping bags of mail amongst the wreckage (this also included forged stamps, though one infamous version with a skull superimposed over Hitler's face was likely never part of the operation). Though the letters were addressed to real people, the contents were propaganda. Dropped leaflets weren't always read — German civilians were reluctant to be seen scanning Allied material in public — but it was hoped that some might actually read the material if they were in private.

The planned aerial bombing run really did take out a German mail train in February 1945. Minutes later, planes dropped the bags of mail, addressed to businesses as personal mail was no longer delivered at this point in the war. For the next two months, similar deliveries took place, pushing some 96,000 forged letters into Nazi Germany. Some made their way into the intended recipient's hands, but it's unclear if they had the intended effect.

Germany had bafflingly bad operational security

Just about any war requires some level of operational security; essentially knowing who you're talking to, and what you're both talking about. But that appeared exceptionally difficult to remember for some German officials during WWII, even when they were prisoners of war.

Nazi generals held at the British estate of Trent Park were allowed to keep servants and enjoy rarefied rations like wine. Only, they were thoroughly bugged. What British listeners heard wasn't just incidental, either. The talkative generals divulged much about Germany's weapons program, including a staged V2 launch site taken out by the British, as well as acknowledging the ongoing Holocaust (some attempted to play stupid at postwar trials).

Serious intelligence leaks didn't just happen in enemy territory. Germany's head of intelligence, Wilhelm Canaris (pictured above), was both a high-ranking Nazi official and secret anti-Nazi who was actively working to overthrow Hitler (though he also was ordered to help blow up America, so don't give him too much leeway). Though definitively part of the regime, Canaris was reportedly shocked by atrocities committed against Jewish people and worked to bring information about this to the wider world, even personally saving seven Jewish people and helped get them out of Germany. By early 1943, he was actively planning Hitler's assassination with co-conspirators, purposefully misleading officials, appointing anti-Nazi friends, and was meeting with enemy representatives in private. Canaris was finally arrested after a failed 1944 assassination attempt against Hitler and executed in a concentration camp in 1945.

One Belgian pilot was demoted and awarded after an unauthorized raid

Defying orders is generally frowned upon in the military, but seeing one's homeland hit hard by Nazis can turn anyone into a bit of a rebel. Such was the case of Jean de Selys Longchamps, a Belgian pilot who, by 1943, was serving with Britain's Royal Air Force. In January of that year, he and another pilot were ordered to strike a railroad in Belgium, then return to their southern British base. But after completing the mission, De Selys peeled off and made for Brussels. Despite the very real possibility of being shot down and captured by the Nazis — something the RAF had specifically warned against — De Selys flew at terrifyingly low altitude towards the city's Gestapo headquarters.

He thoroughly shelled the Gestapo outpost, then released two large flags — of Britain and Belgium — followed by a series of smaller Belgian flags. De Selys killed four German officials and became something of a folk hero for the city's resistance, though just over half a year later he died in a plane crash. Before all that, he returned to his base in Kent, England, where he was demoted from his position of flight leader (though this was actually decided before he took off on his unauthorized mission). De Selys — who technically asked permission for the mission and was never explicitly told not to go — was also awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his actions.

Kamikaze missions weren't limited to planes

Today, the kamikaze pilots of WWII Japan are one of the more notorious details of the war. With its back against the wall, Japan sent pilots on final missions to attack U.S. ships, with the understanding that they would never return home. But while aircraft have typically been the focus of this subject, pilots were far from the only Japanese WWII service members who were asked (or pressured) into giving up their lives for the war effort. Some were packed into winged missiles, kicking on a final rocket-propelled stage that would blast them into the target at over 600 miles per hour.

Some Japanese sailors were tasked with piloting torpedoes, known as kaiten and which debuted in 1944. Some were actually successful, including the first kaiten attack in November 1944 on Allied ships in Truk (now Chuuk) lagoon, and another 10 or so kaiten missions were carried out. Other sailors were transformed into kamikaze divers known as fukuryu, armed with mines to place on the hulls of enemy ships, though the fukuryu program didn't go much past the training stage.

Japan also attempted kamikaze motorboats called shinyo. Like their aircraft counterparts, munitions-loaded shinyo would be piloted into Allied craft to explode. An estimated 6,000 were built, typically out of cheap plywood and with a 500-pound bomb in the bow. Later versions included a serrated harpoon on the front, after Allied officials caught on and attempted to block shinyo with nets.

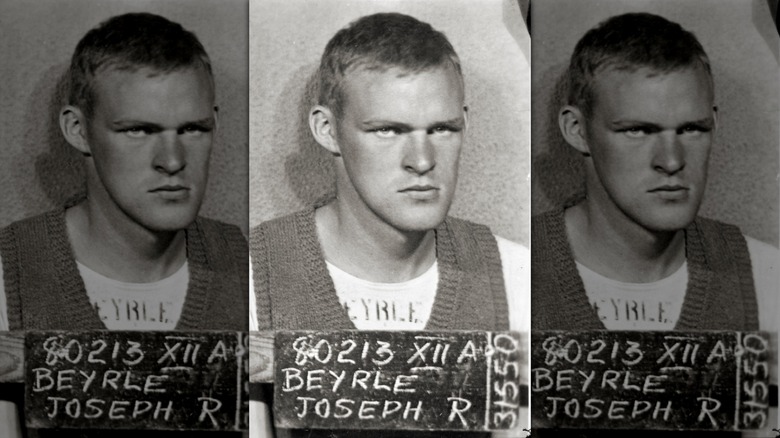

One man served with both the U.S. and Soviet armies

"Jumpin' Joe" Beyrle was a U.S. paratrooper who, by 1944, was tasked with descending into Nazi-held France to supply the French resistance with gold coins. Beyrle and his fellow paratroopers did this twice before another mission that took place during the D-Day invasion. But, that time, as Beyrle's transport plane was taking heavy anti-aircraft fire, he was forced to jump at the terrifyingly low altitude of 400 feet. He survived, but was captured, interrogated, and sent to a POW camp.

Beyrle escaped one camp by bribing guards with cigarettes, but was quickly apprehended and tortured by the Gestapo. The German military complained that the civilian Gestapo was encroaching on its territory, so the POWs were turned over to military officials. Beyrle escaped yet another camp and came across a Soviet tank company, whose commander allowed Beyrle to join. He was wounded in a German attack and sent to a Soviet hospital where he met big-name military commander Georgy Zhukov.

As Beyrle recalled it, Zhukov pulled some strings and had a letter delivered to the American. Beyrle couldn't read the Cyrillic text, but was told it would get him home. Indeed, it did help him reach the U.S. Embassy in Moscow. After some work to convince officials he really was Beyrle (he'd been declared dead), Jumpin' Joe made it back home to Michigan. There, he married his wife JoAnne in the same church where, just a short while earlier, they'd held his funeral.

Some British people sheltered in cages

It's hard for some of us to fully appreciate the terror of living in Britain during the Blitz and other bombing campaigns of WWII. At some of the most vulnerable moments, like in the middle of what should have been a restful night of sleep, the Luftwaffe might appear overhead bearing bombs and raining down destruction on your home. Many British people supposedly reacted with what was called the "Blitz Spirit," a variation on the classic stiff-upper-lip stoicism that led them to cheerfully persevere, but research indicates that people were rightfully frightened of being bombed into oblivion. Why else would someone send their children to the countryside or descend into bomb shelters when air raid sirens blared?

Some communal bomb shelters were converted tube stations, while families might choose to take cover in quasi-underground Anderson shelters typically installed in gardens. But some found themselves in situations where it might be difficult to leave the home and find shelter elsewhere, and their answer was a contraption known as the Morrison table shelter.

Meant to be used inside homes on the first floor, the Morrison shelter was effectively a self-assembled steel cage. At the sound of air raid sirens, inhabitants could crawl into one or even regularly sleep inside. As the name indicates, it could also be used as a table, further justifying its hefty footprint in cramped British homes. By 1945, it's estimated that one million had been put into place in the nation.

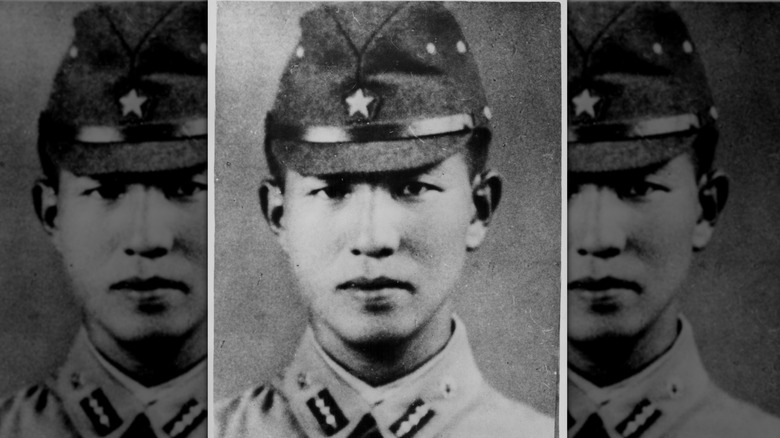

One Japanese soldier kept fighting until 1974

For a small group of Japanese soldiers ensconced deep within the jungles of the Philippines, the war continued for decades. One especially dedicated lieutenant wouldn't emerge until 1974, making him the last Japanese soldier to surrender. That lingering combatant, Hiroo Onoda, was conscripted in 1942, and eventually ended up on the island of Lubang.

Along with the rest of his unit, Onoda was tasked with taking out Allied troops and the airfield they'd set up on the island, but the job failed and they took cover in the thick jungle. This was towards the end of 1944, and the war was soon over, but the group refused to believe it, assuming the leaflets dropped on them were propaganda meant to lure them out of hiding. Commanded to stay alive, Onoda and his group just kept fighting World War II. Out of the original four, one surrendered in 1950, one was killed in 1954, and another in 1972, leaving Onoda on his own to continue stealing food from locals (and, if reports are to be believed, occasionally attacking them).

Explorer Norio Suzuki finally came face to face with Onoda in 1974. Suzuki had to return with official documents and a group that included Onoda's retired commander to officially relieve him of duty. When he returned to Japan, Onoda became a sort of celebrity, publishing a popular memoir and attempting to start a new life in Brazil. Onoda died in a Japanese hospital in 2014.

Operation Mincemeat was a ghoulish attempt to fool Axis forces

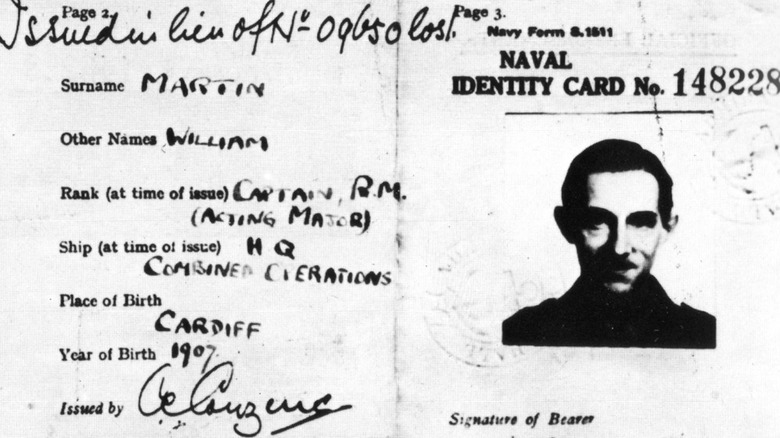

Britain was clearly ready to try almost anything by 1943, including conscripting an unclaimed corpse. Known as Operation Mincemeat — yes, it really was called that — the affair was directed by the MI5 intelligence agency. The idea was to find a body, plant forged documents on it, and allow the remains to wash up on a Spanish beach. There, it would be found by locals and ferried on to the Nazis.

The body in question belonged to an unhoused man, Glyndwr Michael, whose true identity wouldn't become public until 1997. MI5 gave him the new identity of Major William Martin, a Royal Marine whose pockets would be filled with personal ephemera and military documents referencing a planned Allied invasion of Greece and a false invasion of Sicily. Another letter claimed Martin was an expert in amphibious invasions and made a joking reference to Sardinia, a large Mediterranean island northwest of Sicily.

Deposited in the Atlantic by a submarine crew, Michael/Martin's body was found by fishermen in Huelva, Spain. Spanish officials promptly turned the documents over to Germany, which was all the more eager because it intercepted faked communications from Britain urging the retrieval of those sensitive letters. Those documents were returned to London, but it was obvious someone had read them first. Afterward, Hitler began moving troops toward Greece and Sardinia in anticipation of an Allied invasion, drawing resources away from the actual July 1943 landings in Sicily.

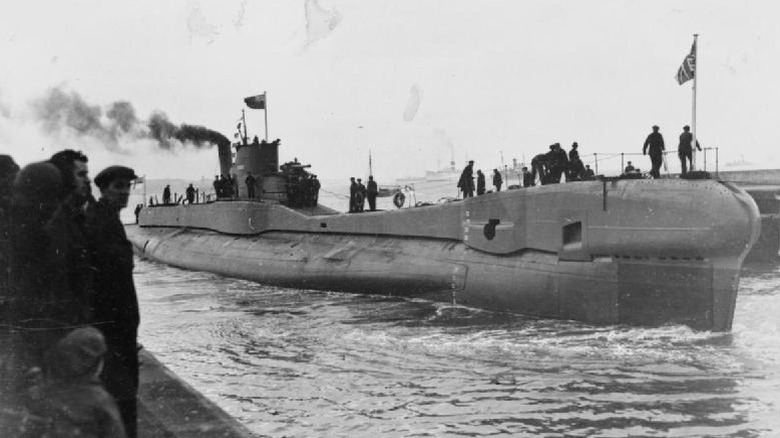

A reindeer lived on a British sub for six weeks

Even if you've never been on a WWII submarine before, you probably know that the quarters inside them were seriously cramped. But one British submarine crew had to make space for a reindeer. It happened in 1941, when the HMS Trident was on patrol aiding the Soviet Navy. As the story goes, the Trident's captain, Geoffrey Sladen, was spending some downtime with a Russian admiral. The conversation somehow turned to Sladen's wife, who had been having trouble pushing a baby stroller through the snow. The Soviet officer is said to have declared Mrs. Sladen was in need of a reindeer ... then actually delivered the animal to the Trident.

The sailors named her Pollyanna. The Soviets helpfully provided some moss as reindeer feed, but when that ran out, Pollyanna was given food scraps from the sub galley (and allegedly ate a navigation chart). While she was crammed into the sub for the next six weeks, she took in fresh air at the main hatch while it was at the surface.

When the Trident docked back home, Pollyanna seemed to be doing just fine. Indulged as she was with human food, she had grown a bit large and needed some leverage to get her out. From there, she made her way to the London Zoo and lived there until 1947. Though it's said she habitually ducked down whenever submarine-like sirens went off, Pollyanna surely appreciated having more room for the remainder of her life.

People still aren't sure what the foo fighters were

Pilots during WWII already had plenty to worry about, but when strange lights began to appear at the tips of their wings, it must have seemed like the last straw. Was this another Nazi weapon? Some strange atmospheric phenomenon destined to crash their plane? Hallucinations? Heck, little green men from outer space? Known as "foo fighters," these little lights came in a variety of colors — some crews reported orange balls of light, others green or red — and managed to keep pace with speeding craft through all sorts of maneuvers. Appearing alone or in groups, none were ever picked up on radar.

Though some crew later admitted to being rightfully frightened, foo fighters never appeared to cause any damage, striking out the possibility that they were part of a German offensive. Given that they never showed up on radar, the foo fighters were unlikely to have even been solid. Military investigations followed, but all concluded with the professional version of a shrug, leaving everyone without much of a conclusion as to the identity or purpose of the eerie lights.

Even today, no one is totally sure what the foo fighters were, though modern scientists do have some ideas. One suggests that these lights were actually plasmas, ionized gases in the atmosphere that collected around electrically charged parts of airplanes. Still, without direct observation, it's difficult to confirm this theory, and the foo fighters remain a strange mystery.

There is a weird fixation on Hitler's globes

Hitler is so broadly awful that even his office supplies have drawn attention. Maybe the interest in his office globes has something to do with the 1940 satirical film, "The Great Dictator," in which Charlie Chaplin plays a buffoonish dictator who dreamily dances with a globe while contemplating world domination. When it comes to real globes, a massive one called the Columbus Globe for State and Industry Leaders is especially arresting. It was made in two small runs in 1930s Berlin, and Hitler had an especially large model in his chancellery office.

Cartographer Wolfram Pobanz told The New York Times in 2007 that he was fairly sure at least one smaller from Munich (complete with a bullet hole) was really owned by Hitler, but the one in Hitler's Reich Chancellery office remained at large. Pobanz argued that another bullet-struck globe in a Berlin museum actually belonged to foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, not Hitler.

Another Hitler-owned globe was snatched up by U.S. Army Warrant Officer John Barsamian, who took it as a souvenir while patrolling a Nazi retreat in Berchtesgaden, Germany. Seeing as it was May 1945 and Germany was clearly out of the war, it's not as if Hitler — who had died by suicide on April 30 — was coming back to claim it. Barsamian took it back to Oakland, California, where it sat next to the family piano for decades. It finally went up for auction in 2007.