17 Infamous Events That Were More Horrific Than You Realized

In a world that often seems chaotic, it's natural to try to insulate oneself from all the bad news that's constantly available on every feed and crawl. If you could do something about the earthquake or war or product recall or space robot invasion, you would, but realistically, there's not much good that comes from simply knowing grim statistics.

Avoidance of some of the worst information out there is, to an extent, self-care: The human mind is simply not equipped to absorb every terrible thing that's happening across an entire planet. In an evolutionary eyeblink, we've gone from mostly just chilling in villages to having more information than we could ever meaningfully internalize, and it's okay to chill. The downside of this self-preservation tactic is that occasionally, you'll realize that a historical event or news story that brushed past you was actually really, really bad, like history-book benefit-concert awareness-ribbon bad, forcing you to research the catastrophe so you can nod with the right amount of somber reflection if it comes up in conversation.

Waco siege

The Clinton years can seem like a hazy dream now: an island of stability and shoulder pads before the chaos of 9/11, wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and the Great Recession. It's easy, from this distance, to forget some of the biggest news stories of the '90s, including the siege of the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas, and the standoff's fiery end.

The Branch Davidians were a splinter group of the Seventh-Day Adventists who, under leader David Koresh (born good old Vernon Howell), began stockpiling guns. It was this, not Koresh's reputed marriages to underage girls, that brought the attention of federal law enforcement. The ATF believed the Branch Davidians to have an arsenal of over 100 firearms, 200,000 rounds of ammo, and grenades and launchers, a worrying hoard even in gun-loving Texas. An initial raid to arrest Koresh and execute a search warrant led to an exchange of shots that killed four federal agents and (probably) six compound residents.

Federal forces descended in force on Waco to lay siege to the Davidian settlement and force out Koresh and his acolytes. Some of Koresh's followers were allowed to leave, but the remainder stayed defiant even when the ATF tried to annoy them into submission with sleep-disrupting floodlights, blared Tibetan chants, and cuts to the power supply. When U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno gave the order to storm the compound after 51 days, ATF agents began firing tear gas; the Dravidians began shooting each other and setting fires to avoid being taken alive. More than 70 people died in Koresh's last stand, among them 25 children. Reno and the ATF were heavily criticized, and the fiasco inspired further anti-government extremism in the United States.

Challenger disaster

In late January 1986, a cold snap hit Florida, icing the central part of the state — annoying, but surely more a problem for vacationers and citrus farmers than astronauts expecting to lift off for a mission. Unfortunately, this unusual cold damaged a rubber O-ring on the space shuttle Challenger, which ultimately led to a leak in a fuel tank, resulting in a cascade failure and an explosion 73 seconds after takeoff, which claimed the lives of the seven crew members aboard the craft.

The Challenger mission's primary goal was to deploy a satellite from the shuttle. The shuttle's launch had been heavily publicized due to the presence of Christa McAuliffe, a teacher who had won a contest to train as an astronaut as part of an educational outreach program. After a successful launch, she was to tour the country teaching American schoolchildren about space and the space program. McAuliffe was not the only civilian aboard, as Gregory B. Jarvis, a Hughes Aircraft Corporation researcher, was also joining the five NASA crew members. The NASA complement comprised commander Francis R. (Dick) Scobee; pilot Michael J. Smith; and mission specialists Judith A. Resnik, Ronald E. McNair, and Ellison S. Onizuka.

A minor blessing was that the crew likely lost consciousness very shortly after the disaster began, with death from asphyxia following and sparing them the fiery plunge into the Atlantic Ocean. (It took over an hour for all the fragments to land.) A subsequent inquiry blamed NASA in part for an overambitious flight schedule in which the agency tried to do too much with limited resources.

Bhopal chemical leak

Before 1984, Bhopal, a mid-sized city in central India, might have been best known for its historic sites, including palaces, forts, and an artificial lake dating from the 11th century. On December 3, 1984, unfortunately, Bhopal became known as the site of the worst industrial accident in history (so far, admittedly). A leak at a poorly maintained pesticide plant run by American multinational Union Carbide belched 45 tons of the toxic gas methyl isocyanate over the city. The heavy, volatile gas blanketed Bhopal, causing burns and irritation to the lungs, eyes, and skin of those exposed and panic among those trying to flee the poisoned city.

Amnesty International notes that more than 7,000 people died from the initial exposure, with a minimum of 15,000 more succumbing to aftereffects over time and 100,000 people suffering from disabling injuries, per a 2004 report. Even these huge numbers are likely underestimations, as more than 600,000 people had filed claims by the time of the report 20 years after the incident. Union Carbide cut a deal not with the survivors, who were ignored in the negotiations, but with the Indian government, ultimately paying the equivalent of a few hundred dollars per claim to victims and survivors. Union Carbide blamed an unnamed saboteur for the leak, arguing that this limited their liability. Meanwhile, the plant continued to leak poison to such an extent that a court order was issued in 2004 to provide Bhopal residents with fresh water, as the groundwater was still contaminated.

A minor casualty of Bhopal was the reputation of everyone's favorite Albanian nun with a complex legacy, Mother Teresa. The tone-deaf saint visited shortly after the disaster, noting that she had seen worse suffering and the most important thing was not justice, not help, but that the victims forgive.

Siege of Leningrad

The Siege of Leningrad was one of the central pillars of Nazi Germany's war effort against the Soviet Union and one of the most important battles of World War II. Leningrad was both one of the Soviet Union's biggest and most culturally important cities but also a key port, and its loss would deprive the Soviet state of access to the Baltic Sea. The siege lasted from September 1941 to January 1944, a staggering 872 days of terror, starvation, cannibalism, and ruin.

By late autumn of 1941, Leningrad and the 200,000 Red Army defenders assigned to the city were encircled by German and Finnish forces, with all connections to the rest of the Soviet Union severed. Occasional supplies came in across Lake Lagoda by barge or, in winter, by sleds across the frozen surface, and by these same routes the old, the young, the sick, and the injured were evacuated. German guns, though far away, still intermittently pelted the city. Meanwhile, within Leningrad, the arms factories kept cranking out materiel, the Soviet secret police kept terrorizing suspected traitors, and 2,000 people were arrested for cannibalism in the first six months of 1942. (The more squeamish ate wallpaper, makeup, and pets.)

Improvised vegetable gardens within the city and a loosening of the German noose as losses mounted for the invaders made 1943 marginally easier, but evacuations and an estimated 800,000 deaths from cold and hunger meant that city of 2.5 million was reduced to 600,000 at liberation. One of the survivors, happily for music, was composer Dmitri Shostakovich, whose Symphony No. 7 was performed in Leningrad during the siege and broadcast around the city in an act of defiance.

Great Leap Forward

Most people would consider gaining control of mainland China after a grueling civil war a victory, a real career capstone, but Mao Zedong was just getting started. Unfortunately for tens of millions of his countrymen, Mao thought that what China needed most was industrial modernization, and so he turned to the Soviet Union for a model. It cannot be answered whether he did not know or did not care that forced collectivization's disruptions and inefficiencies had starved six to eight million Soviets.

Taking cues from the Soviet crushing of an uprising in Hungary, Mao's orders stifled dissent and identified alleged right-wing saboteurs starting in summer of 1957, so by the beginning of the Great Leap Forward plan in 1958, no one was willing to point out the recklessness of it. The attempt at a quick-'n'-dirty industrial revolution lost China 10% of its forest and resulted in low-grade iron made from melted-down consumer products, not usable steel from fresh ore.

Meanwhile, unrealistic quotas, driven by ideological fervor rather than an understanding of how wheat works, meant that rural areas were forwarding more food to cities than they could afford to part with. (And as usual for grand ideological national projects, those suspected of holding back food for their families were beaten or tortured.) By summer of 1960, true famine had arrived in parts of rural China, with people dying in colossal numbers. The scale of the disaster and the secretive nature of the Chinese state mean that numbers are very hard to come by, but Western estimates range from 23 to 55 million dead in the famine. The official Chinese line blamed weather and the Soviets calling in Chinese loans; even today, Chinese accounts seldom blame Mao and his government.

Lake Nyos disaster

On August 21, 1986, a previously obscure type of natural disaster hit a rural area of the West African nation of Cameroon. Lake Nyos, previously an attractively still, blue lake, had vented an enormous cloud of carbon dioxide, with the only warning signs a rumbling sound and a sudden spray jetting out of the lake. Carbon dioxide is heavy (you know, for a gas), and so it rolled out along the adjacent lowlands, displacing the oxygen. When the clouds cleared, 1700 or so people had died, along with many of the animals the local farmers kept. Survivors had been unconscious for up to 36 hours, and some woke to find themselves with skin lesions akin to chemical burns.

The Lake Nyos disaster's only real precedent was a similar but much smaller event at nearby Lake Monoun that had occurred two years earlier, killing "only" about 37 people. Some local people believed the lake was home to malicious spirits, which may hint at previous incidents that escaped scientific recording. The ultimate explanation for the Lake Nyos event was that carbon dioxide was bubbling into the lake from an adjacent geological vent but was kept under the water by its weight; when something upset the balance, the gas erupted.

Lake Nyos has since been equipped with structures to release future gas buildup at a safe rate. Concern has since turned to Lake Kivu, which borders Rwanda and Congo and may also be at risk of an eruption like the Lake Nyos event. A Rwandan company, KivuWatt, is currently trying to defuse the problem (and make a little money) by extracting trapped methane from the gas layer and burning it for power.

Encephalitis lethargica

The great Spanish flu pandemic that began in 1918 grabs most of the public attention devoted to "epidemics coinciding with World War I," but it was neither the first nor the creepiest. Those laurels belong to encephalitis lethargica, a never-fully-explained illness that spread intermittently from the winter of 1916-1917 to 1928. Its origins are muddy due to the war, but the disease seems to have arisen in Romania, reached and savaged Vienna in 1917, from there spread across Europe, and by 1919 was battering North America and Asia.

Encephalitis lethargica had one hallmark symptom: enormous sleepiness. It clearly affected the brain or nerves, but the specific symptoms varied wildly, with some people becoming sleepy and then dying a few days later, others becoming manic, and still others simply being ill (and sleepy!) for a time before apparently recovering. Survivors, however, were not wholly safe: Some years after the initial illness (usually one to five, but sometimes decades), a patient could develop serious Parkinson's-like symptoms of tremor, involuntary movements, speech difficulty, and psychiatric problems.

A causative agent for the illness was never discovered, and a true death toll was never established because the symptoms were so variable that the disease could have been overdiagnosed as often as it was missed. Reports are even unclear if it was easily transmitted from person to person. Neurologist Oliver Sacks (pictured) wrote about his work with survivors in his 1973 book "Awakenings," in which survivors with serious after effects were treated with drugs that temporarily helped them improve; this work introduced the bizarre story of encephalitis lethargica to a new generation, but Sacks was, like his colleagues, unable to fully explain the enigmatic disease.

Partition of India

When the United Kingdom decided to leave India, it decided to go ahead and hurry. Hindu-Muslim tensions had already claimed lives, and the last viceroy, Lord Mountbatten, arrived on the subcontinent with instructions to get Britain out under the best circumstances he could wrangle. In practice, this meant he had less than a month to draw borders for Hindu-majority and Muslim-majority states, a process complicated by the fact that there was no way to make Muslim-majority areas contiguous, so the Pakistan-to-be would be in two parts.

The result was terrible. Big and populous Punjab and Bengal were carelessly cut in two, the Sikhs found themselves on both sides of the emerging border, and some divided villages argued among themselves whether they were in India or Pakistan. Naturally, the people involved decided to try to solve the problem with horrific sectarian violence, even as millions of people bolted to get across the border to the new country they thought was safer. Some 15 million people were displaced and 2 million killed in the immediate aftermath.

The wars resulting from partition are not over. India and Pakistan have been to war four times, thrice over the divided mountain province of Kashmir, which both want, and once when India intervened in the Bangladeshi war of independence to ensure that "East Pakistan" could break free of the genocidal government in the west. India and the remainder of Pakistan are both now nuclear states, raising the stakes for an unimaginably bad outcome.

Hurricane Camille

The last few decades of turbocharged hurricanes thwomping coastal cities and, increasingly, causing devastation further and further inland have pushed some of the previous "worst hurricane ever" record holders further back in public memory. One of these was Camille, which in August 1969 hit the Mississippi coastline so hard it destroyed all the wind gauges, leaving scientists to estimate its winds at topping 200 miles per hour. Tides in the Gulf topped 24 feet, and inland flooding from Camille's remnants led to devastating mudslides in the Appalachians.

Camille's impact was worsened by the fragmented media market of the Gulf Coast. In the days before the all-news-all-the-time media landscape, BIloxi was the biggest city on Mississippi's coast, but some residents preferred to tune in to stations in nearby New Orleans. Panicked Biloxi newscasters reacting to detailed reports gave emotional evacuation advice; New Orleans newscasters read general news reports that said a hurricane was coming but did not emphasize its severity. Local optimism that the storm would turn toward Alabama or Florida further dampened evacuation efforts. So when Camille howled ashore just before midnight on August 17, hitting Bay St. Louis and Waveland directly, some people were woefully unprepared.

Some 150 people died on the Gulf Coast as a result of Camille, 21 of them in a single obliterated apartment building. They were joined by more than 100 people in Virginia flooding and landslides that would be remembered as among the worst natural disasters ever to strike the Old Dominion.

The Dirty War

When Juan Peron, president of Argentina, died on July 1, 1974, he left the government of the largest country in the Spanish-speaking world to his wife. Not the still-revered Evita, who had died in 1952, but his third wife Isabel, who lacked her predecessor's popularity and political instincts. Isabel was utterly defeated by the political violence and inflation she faced (which, in fairness, would have challenged far more astute politicians), and in 1976 she was overthrown by a military junta fronted by the sinister lieutenant general Jorge Videla.

Initially, much of the Argentine population was willing to put up with the new dictatorship's heavy hand to restore stability to the nation. As time went by, more and more people knew someone who had been tortured in one of the government's installations ... or who had simply disappeared, taken by military forces and never returned. Some of these captives had been blown up in fields; others were flown out over the water and dropped from planes. (This came to light when the dead washed ashore in a justifiably concerned Uruguay.) In a particularly sinister touch, the dictatorship stole babies from the politically undesirable and placed them with childless couples connected to the government. All told, 10,000 to 30,000 Argentines were killed by their own government during the repression.

To distract from all this and try to defuse public indignation, the government invaded the British-held Falkland Islands, long a target of Argentinian aspiration, in 1982. Whoops-a-daisy, they lost, and the military government was discredited and defeated in a 1983 election that restored democracy to the country.

Second Boer War

After the British took control of the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa during the Napoleonic Wars, a number of dissatisfied Dutch colonists who had stolen the land fair and square from the Africans flounced inland. They eventually created two statelets, called the Boer republics after the Dutch word for "farmer": Transvaal and the Orange Free State. By 1880, the British were concerned that the Boer republics threatened their continued control of the Cape and sat on a bunch of gold and diamond mines the British would like. The first attempt to gobble the Boer republics failed, so when it was time to try again in 1899, they were ready to fight hard.

Meanwhile, the Boers were ready to fight too, laying siege to several towns and beating the British in early battles. This early success was reversed in the first half of 1900, however: The Boer sieges of Ladysmith and Mafeking were broken, and by early June, the capitals of both Boer republics had been taken. All that was left for the British was to mop up about 20,000 die-hard Boers. It only took two years of brutal fighting and scorched-earth savagery.

The new British general, Lord Kitchener, decided to burn as much of the Boer territory as he could to prevent the fighters from being provisioned. Women and children thus rendered homeless could be forced into concentration camps, as could Black civilians who were wanted as mine laborers. (Remember, Britain abolished slavery in 1834, but ... c'mon, there's gold!) Bad food and sanitation in the camps led to an estimated 50,000 or more civilian deaths beyond those resulting from other actions of the war, with 40 Boer towns and 30,000 farms destroyed.

Philippine War

By 1898, the rickety Spanish empire was reduced to a handful of islands, which it was determined to keep. American horror at Spain's repression in Cuba, along with good old-fashioned expansionist lust for territory, led the rising and the waning powers to war. By the end, the United States was able to lean on Spain to hand over Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines while granting Cuba its independence (a decision no American president has ever regretted).

The people of the Philippines were generally not thrilled about trading rule from Madrid for rule from Washington. Emilio Aguinaldo – a general who had declared Philippine independence, established a republic, and cleared the Spanish from much of the country while the United States fought on other fronts — hoped the United States would protect the new country, not gobble it. Alas, Uncle Sam was hungry and sent 70,000 soldiers to pull the islands firmly into the American orbit.

A savage guerilla war followed, with United States forces working to sap Philippine resistance by burning villages and waterboarding captives. Approximately 20,000 Filipino soldiers died, a toll dwarfed by the 200,000 estimated civilian deaths; American forces lost 4,000. The Philippines stayed under American control until they were occupied by the Japanese during World War II, ultimately gaining their independence in 1946 — on July 4, naturally.

Pacific measles outbreak

In late 2019, shortly before a different outbreak focused the attention of the world, measles galloped through several Pacific Island nations. Tonga, Fiji, and American Samoa all reported cases, but the worst hit was independent Samoa. Samoa was especially vulnerable due to low vaccination rates in the country, which had been targeted by anti-vaccine activists. The anti-vaxxers' efforts had been aided by a bizarre case of medical recklessness: Nurses had mixed the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine they were to administer not with water, but with a muscle relaxant (expired to boot), and this had killed two children.

Measles would go on to kill far more Samoan children than the nurses' error. A Lancet report on mitigation measures reports 81 deaths, most of them children under 4 years old — this is in a country of only about 200,000 people, a little bigger than Little Rock, Arkansas. The BBC reports that 8% of the population under 15 years old died. Once the scale of the outbreak was evident, Samoan authorities closed schools, mandated vaccinations, and forbade gatherings of children, bringing the outbreak under control and limiting it to south of 6,000 infections.

But the survivors may not have the all-clear. Measles is not only one of the most contagious viruses known, but it also targets particular immune cells, eradicating the body's records of how to fight previous germs it has encountered. People who survive measles have to build immune memory from scratch — and may succumb to another illness while their immune systems rebuild themselves.

The Great Dying

In a list of disasters that kill thousands or millions of people, the Permian-Triassic extinction stands out with a human death toll of zero — we just weren't around yet. But had the chips fallen very slightly differently, this extinction event might simply have prevented us from emerging in the first place. Whatever happened pruned the tree of life with lumberjack savagery and came uncomfortably close to wiping out life on Earth. About 90% of all species on the planet were swept from the board in a devastation that left nothing untouched, dramatically reducing the diversity of life on Earth. (They don't call it the Great Dying for nothing.)

The extinction may have taken place over a span of about 100,000 years (peanuts for evolution and geology). Possible causes include a meteor impact like the later one that eliminated the dinosaurs, mega-volcanoes in Siberia, stagnant ocean currents that permitted a choking buildup of carbon dioxide, or a combination of these factors. One of the few beneficiaries seems to have been wood-eating fungi that gorged on the remains of most of the trees in the world. Survivors included synapsids, a kind of reptile whose eventual mammalian descendants include human beings, the only species we yet know of capable of both causing and worrying about mass extinctions.

Irish potato famine

Phytophthora infestans is an appallingly efficient plant pathogen, contagious and lethal. It affects potatoes and tomatoes, rotting and killing them with a disease called "late blight," though similar organisms are hazards to a much wider variety of crops. Dangerously and insultingly, Phytophthora infestans can also destroy already-harvested potatoes, meaning that not just active crops but food stores are at risk.

The fungus first came to general attention when it appeared in the United States in 1843, and by 1845 it was souring fields of potatoes in northern Europe and had reached a first dangerous tentacle into Ireland, which relied heavily on the potato to feed its large population of poor farmers. By early 1846, it was all over the island, and the Irish potato famine had begun. Ireland was then part of the absurdly powerful British Empire, which addressed the problem in Ireland in a variety of completely ineffective ways: sending corn, blaming God, passing the buck to local Irish authorities, and yammering about laissez-faire economics. None of these strategies consistently filled Irish stewpots.

Foreign relief efforts sent money; even the good people of the Choctaw Nation raised and sent $170. A million Irish people died, and nearly 2 million left the country in search of a future with food in it. Independent Ireland's population now rests at about 5.2 million and Northern Ireland at a little under 2 million: Even today, Ireland's population has not yet recovered the level of over 8 million recorded at the last pre-famine census of the island in 1841.

French Revolution

Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette were certainly the fanciest victims of the French Revolution, but they were very, very far from being the only ones. The French Revolution was a bloody sprawl of interconnected riots, battles, wrangles, and reactions, which reached its most appalling height in the Reign of Terror of late 1793 to mid-1794.

In 1793, France was at war with most of the rest of Europe, which wanted France to shut up and stop giving people ideas. Panicked by the strength of the alliance fighting France and jittery about real and perceived counter-revolutionary forces within the country itself, the government of the day cooked up a deliberately vague treason law that could be applied to nearly anybody. Over 16,000 French citizens were sent to the guillotine by this law, and thousands more were killed in less organized violence that included mass drownings in Brittany and close-range cannon fire in Lyon. The Vendée, a rural province in France's west, dared to resist conscription and was so savaged in response that 20% of its population may have died.

And this is just the start. To take a long view, the war that began when Europe objected to France's plan to overthrow and kill its own monarchs led directly into the Napoleonic Wars, which lasted until 1815 and saw most of the capitals of Europe overrun by hostile armies. All in all, perhaps they should have just eaten the cake.

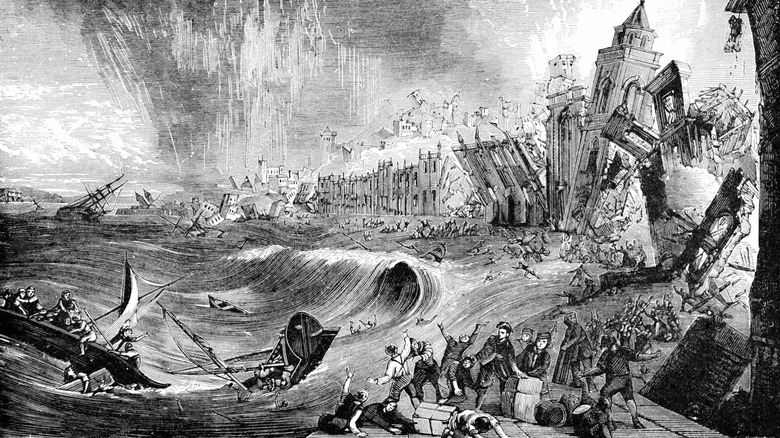

Lisbon earthquake of 1755

On the morning of November 1, 1755, an earthquake hit Lisbon, the capital of Portugal. Modern estimates based on a subsequent compilation of witness accounts place the quake at 9 or a little less on the Richter scale, lasting for seven to nine minutes — for reference, Led Zeppelin's "When the Levee Breaks" is a little over seven minutes long. An hour later, the tsunami triggered by the shaking hit, adding to the damage and death toll but failing to extinguish all of the fires that had broken out across the ravaged city. The earthquake was felt in Morocco, Spain, and Algeria; associated tidal waves hit French Martinique in the Caribbean, nearly 3,800 miles away.

The scale of the damage means that estimates of the people who died vary widely, ranging from 12,000 to 40,000 of the roughly 200,000 people who then populated the city. Many of them were killed when the churches in which they were celebrating All Saints' Day collapsed. As many as 12,000 homes may have been lost, along with 46 convents (how many do you need?), all six hospitals, and countless treasures in destroyed libraries and collections. A small comfort is that the palace that housed the Portuguese Inquisition was among the buildings lost.

Countries across Europe sent supplies, with the biggest batch coming from Portugal's ancient ally, England, which sent cash, food, building supplies, and shoes. Today, the event is commemorated with a museum in Lisbon, complete with an earthquake simulator for the extremely curious.