The Most Controversial Books That Were Included In The Bible

The Holy Bible is probably the most discussed, debated, and argued book in the history of humankind, by both people who believe what it says and those who decidedly do not. But even if you believe wholeheartedly the Bible is 100 percent the inspired word of God, the fact is the books were not all written at the same time and human beings–divinely inspired or not–had to decide which of the innumerable works claiming to be scripture actually carried divine authority and would make the final cut. Some books made it more easily than others, and even today churches can't agree on which books are the real deal.

Which books had the rockiest road to travel on the way to acceptance into biblical canon? What were the issues that could cause fourth century dudes to fight and snipe at each other or cause Martin Luther to call a book trash? Read on to find out the most controversial books that still managed to make it into the Bible.

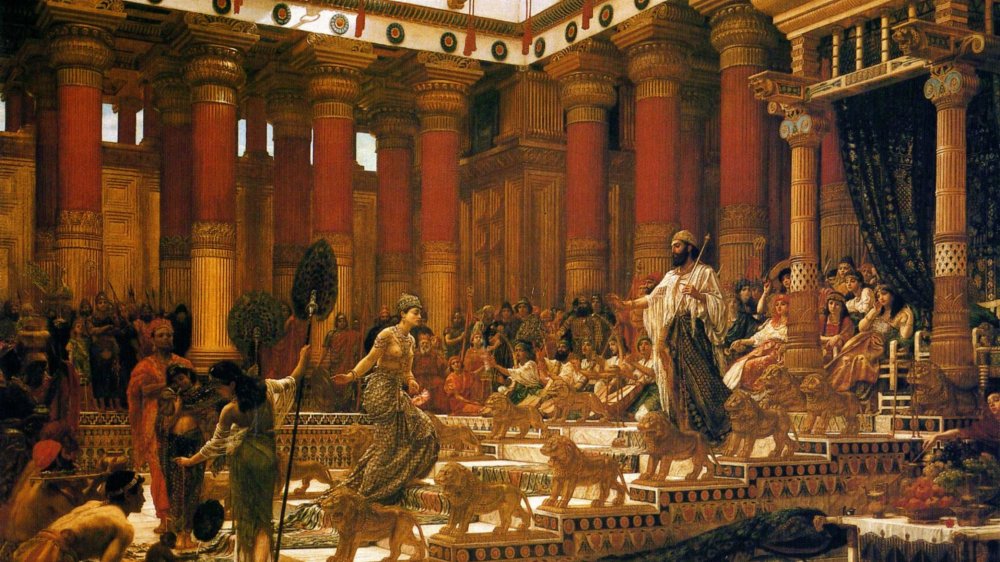

The Book of Esther forgot to mention God

The Book of Esther is the rousing tale of a Jewish woman who saves her people by using her beauty to marry the Persian king and convince him not to do a genocide. It has a villain so hateable you will boo when you hear his name and cheer when he gets hanged on the very gallows he had built for Esther's uncle. It's a tight and engaging story, and it serves to explain the history behind the festival of Purim, which can be somewhat reductively described as "Jewish Halloween." And that's a major source of the trouble it had being confirmed as canon.

As the Encyclopedia of the Bible explains, the first five books of the Bible, the Law of Moses, lay out what had been considered all the obligatory holidays of the Jewish faith, such as Passover, Rosh Hashanah, and Sukkot. The fact the Book of Esther claimed to institute a new mandatory festival was something of a problem among the rabbis. Other issues include the fact the book never explicitly mentions God and it contradicts multiple points of known history. Even more troublesome is the fact the Greek version of the book has large chunks of text not included in the Hebrew original. Ultimately, Jews and Protestants accepted the original version, while Catholic and Orthodox churches use the longer Greek version.

Ecclesiastes is a depressing meditation on the futility of life

Make no mistake about it: the Book of Ecclesiastes is one of the most beautifully written books of the Bible and maybe even one of the greatest pieces of literature in all of human history. It's the source of numerous common expressions and literary allusions such as "eat, drink, and be merry," "the sun also rises," and "nothing new under the sun," as well as being the inspiration for the classic folk song "Turn! Turn! Turn!" It is also a book about depression and how death is inevitable and the futility of existence and how, indeed, the living should envy the dead, and the dead should envy the unborn who have never had to bear the injustice of existence. Beautiful, but bleak stuff.

As McFadyen's Introduction to the Old Testament lays out, the bleak worldview has led to continued concerns over the canonicity of the book. Besides the fact the book seems to suggest there is no justice in the afterlife–a message that contradicts pretty much the rest of both Jewish and Christian scripture–there are some internal contradictions as well, mainly concerning whether it is actually better to be alive or dead. The main things that have kept the book in canon are that the book has long been attributed to King Solomon and the final two verses of the book, which say the only thing worth doing is following God's commands.

Song of Songs is too sexy for the Bible

The Song of Songs, also known as the Song of Solomon or Canticles, is a unique work within the biblical canon, in that it is not at all concerned with God's law or his covenant with the people of Israel or wisdom or, like, morality in general. Together with the original version of Esther, in fact, it is one of only two books of the Bible that don't mention God at all. Instead, the Song of Songs is concerned with only one thing: getting one's bone on and then celebrating that fact through song like the Lonely Island.

As you might imagine, and as the New World Encyclopedia lays out, the book's open and unabashed dedication to the themes of physical and sensual intimacy has created an issue among some religious leaders, especially those for whom sexuality is considered innately sinful. Debate raged among both Jewish and Christian leaders about its continued inclusion in canon. Two main things saved it: first, the longstanding and continued attribution of the work to King Solomon, one of the major dudes of Judaism; and second, a dedicated effort to convince oneself the book is an allegory for the relationship between either God and the Jewish people or Christ and the church. This common but tenuous approach has led to the book remaining in canon as well as centuries of scholars trying to figure out what the boobs are symbols for.

Martin Luther called the Epistle to the Hebrews trash

The Epistle to the Hebrews is usually grouped as the longest of the General Epistles; that is to say, the letters in the New Testament not written by the Apostle Paul. However, the possibility that maybe this letter actually was written by Paul is what lies at the center of the controversy over this book's canonicity.

As the Encyclopedia of the Bible explains, Hebrews was accepted early on as a work of Paul, and by the time of the second century, its canonicity was pretty universally accepted by the Eastern church as having been written by Paul. The Western church, however, had no such unanimity. For them, canonicity relied heavily on apostolic authorship, and while some were willing to accept Hebrews as the work of Paul, not everyone was. By the late fourth century, however, Hebrews was accepted on the strength of its writing and theology despite its mysterious provenance.

This wasn't good enough for Martin Luther, who felt the book's theology contained some "wood, hay, and stubble," and so he relegated it with some other New Testament books to a lesser status. John Calvin didn't think Paul wrote it but thought it was good enough to be in the Bible anyway. There is still no consensus on the authorship of Hebrews, but theories include associates and rivals of Paul such as Barnabas, Priscilla, and Apollos.

The Epistle of James was too Jewish for the New Testament

In the earliest days of the Christian church, there were two general flavors of Christianity: the Gentile-centric approach of the missionary Paul, which said faith in Christ superseded the Jewish law, and the more Jewish style of the Jerusalem church and its leader, James the Just, which said you had to actually, like, do good things to be a good person. You may be able to piece together which side "won" by the fact half the New Testament is made up of the writings of Paul, and James only has one brief letter, which had to fight to be included.

As the Encyclopedia of the Bible says, James is the most Jewish book in the New Testament, focusing on fulfilling Christ's message with the fruits of one's actions rather than the more Pauline message of seeking redemption and eternal life. This Jewish approach to Christianity soon withered on the vine in favor of Paul's more universal style, which combined with the fact the letter was not attributed to one of the Twelve Apostles led to the Epistle of James to be neglected for centuries until authors like St. Augustine stumped for its canonicity. Martin Luther, of course, considered it of secondary canonical rank for suggesting faith alone isn't enough. This despite the small fact James the Just was Jesus's brother.

The Second Epistle of Peter was the most controversial book of the New Testament

You'd think the most controversial book in the entire biblical canon is Revelation thanks to its wild and hard to interpret apocalyptic visions, but there was another book that was even more contentious: the Second Epistle of Peter. As with most controversies over canonicity within the New Testament, the crux of the debate was over the question of authorship.

As Bible.org puts it, "The history of the acceptance of 2 Peter into the New Testament canon has all the grace of a college hazing event. This epistle was examined, prayed over, considered, and debated more than any other New Testament book—including Revelation." There were a few different issues at play. First, the language of 2 Peter didn't match that of 1 Peter–which was more readily accepted as being by the real for real Peter–as closely as the church fathers would have liked. Next, 2 Peter has significant textual overlap with the Epistle of Jude, itself hotly debated. Finally, the name Peter–carrying with it the weight of one of the main dudes of Christianity–had already been applied to numerous heretical texts, such as the Gnostic Apocalypse of Peter, and so the fathers were hesitant to accept 2 Peter without certainty. Nevertheless, while most modern scholarship says 2 Peter is definitely not by the St. Peter, the church accepted its apostolic authority, though early Protestant Reformers were still skeptical.

Which John wrote 2 and 3 John?

There is what could be charitably called an overabundance of dudes named John in the New Testament. There's John the Baptist, John the Apostle, John the Evangelist (i.e., the writer of the Gospel of John), John the Elder (possibly the author of the Epistles of John), and John of Patmos (the author of Revelation). With the exception of John the Baptist, who is definitely his own guy, any combination of the other Johns might or might not be the same person. In fact, the traditional view held by much of mainstream Christianity is all the non-Baptist Johns are the same guy. But arriving at that consensus was not without controversy, and it made the canonicity of the second and third epistles of John questionable for a while.

According to the Encyclopedia of the Bible, the books of 2 and 3 John reference being written by an Elder; likewise, the church father Papias claimed to be a disciple of a certain John the Elder. The historian Eusebius argued John the Elder was not the same person as John the Apostle, thereby calling the apostolic authority of 2 and 3 John into question. The fact these letters were extremely short and generally unrelated to universal issues of the church was also a cause for concern. After the fourth century, however, general consensus agreed on their apostolic origin.

The Epistle of Jude quotes the wrong books

The Epistle of Jude is one of the shortest books in the Bible, with a mere one chapter made up of just 25 verses. It managed, however, to cram in quite a bit of controversy in those few verses, even though there's a chance that like the Epistle of James it was written by one of Jesus's brothers.

As Drummond's Introduction to the New Testament explains, Jude has a number of strikes against it. For one, it shares a number of passages in common with the über-controversial 2 Peter. Secondly, it references and even directly quotes two different apocryphal books: first the Assumption of Moses, which discusses the archangel Michael and Satan fighting over Moses' corpse, and then the Book of Enoch, which discusses the final fate of fallen angels. The brevity of the book and the fact it wasn't attributed to one of the apostles were also concerns for some Church Fathers.

While the association with Jude the brother of Jesus existed early on, some of the phrasing in the book–such as referring to Paul's letters as scripture, and the implication some or all of the apostles had died–caused some to doubt it was written in that Jude's lifetime. It was, however, ultimately accepted, though the Syrian church and later Martin Luther rejected it.

The Book of Revelation was accused of being a forgery

If you've read the Book of Revelation, it might not surprise you it has one of the most contentious paths to canonicity of any book of the Bible. What might surprise you, however, is the controversy was not about the fact the book is a cryptic enigma in which a beast with seven heads and ten horns comes out of the sea and no one can agree on whether that's a metaphor or not. Instead, as Professor Michael J. Kruger points out, Revelation's road to the canon had a trajectory somewhat opposite of most contentious New Testament books.

Some New Testament books were met with a lukewarm response that required the Church Fathers to warm up to them. Revelation, on the other hand, was initially met with an enthusiastic reception, largely thanks to the idea the author of the book was John the Apostle. This idea was accepted for quite a while until a third century author claimed it to be a forgery by the heretic Cerinthus, and others disagreed with its message of a literal thousand-year reign by Christ on Earth. Revelation was eventually affirmed as a book given authority by Church Fathers, but many early Protestant leaders like Martin Luther and John Calvin rejected its apostolic and prophetic authenticity, and even today it is the only New Testament book not read in the Divine Liturgy of the Eastern Orthodox Church.

The Book of Tobit was too cool for Martin Luther

For mainstream American Protestants, the Bible has and has always had 66 books, with 39 in the Old Testament and 27 in the New Testament. As a result, they are frequently surprised to learn Catholic and Orthodox Bibles usually have more books than that. The best known of these books are the group of (usually) 15 books called the Apocrypha by Martin Luther and later Protestants and called the deuterocanon (i.e., later canon) by Catholics. Luther said the books of the Apocrypha were good and worth reading, but not equal to real scripture, largely due to their late date of composition. These books include 1 and 2 Maccabees, Susanna, Bel and the Dragon, and Tobit, among others.

Protestants are unfortunately missing out, because many of these books completely rule. Tobit, for example, as the Encyclopedia of the Bible explains, is the story of young Tobias teaming up with the disguised archangel Raphael to find a cure for his father Tobit's blindness after birds pooped in his eyes, and to battle the demon Asmodeus, who kept murdering dudes on their wedding night. Definitely worth a read, no matter Luther's opinion.

The Third Book of Maccabees doesn't have enough Maccabees

The Greek Orthodox Church used–perhaps self-evidently–the Greek Septuagint as the basis of their Old Testament canon, and so the Eastern Orthodox Bible includes all of the books from the Roman Catholic deuterocanon, but they also felt less of an obligation to draw stark contrast between canon and non-canon than the Western Church did. Since they were more chill about it, their canon includes additional books such as 3 Maccabees and 1 Esdras. This gives the Orthodox Old Testament a total of 49 books versus the 39 found in the Protestant canon.

The Catholic and Orthodox Bibles both contain the books of 1 and 2 Maccabees, which tell of the revolt led by Judah Maccabee and his brothers against the Greek Seleucids and the rededication of the temple in Jerusalem (i.e., the story of Hanukkah). Only the Orthodox canon, however, collects 3 Maccabees, which tells a tale of Jewish resistance in Egypt that actually has nothing to do with Judah Mac or the Seleucids, but rather Ptolemy IV trying to wipe out the Jews with drunk elephants.

According to Catholic Answers, the Western Church rejected it because they deemed it a philosophical treatise that was a work of fiction and actually had nothing to do with the Maccabees. There are actually eight books of Maccabees, but once you get past the fourth one, which is canon in the Georgian Orthodox Church, no one really accepts them as canonical.

The Book of Jubilees is too much for most churches

The widest canon of them all can be found within the Oriental Orthodox Churches of Ethiopia and Eritrea. What is called the "narrow" canon of the Ethiopian church contains 81 books, including all the books of the Septuagint like the Catholics and Greek Orthodox Church use (minus the Books of Maccabees), as well as the books of 1 Enoch, Jubilees, 2 Esdras, the Paralipomena of Baruch, and three books of Meqabyan, also known as the Ethiopian Maccabees, which also have nothing to do with the Maccabees. But the Ethiopian New Testament also includes what is known as the "broader" canon, which contains books of church practices, church ordinances, and a history of the Jews based on the writings of Flavius Josephus. It's ... a lot of books, and probably a lot more than you learned about in Sunday School.

Besides the somewhat psychedelic Book of Enoch, probably the best known book exclusive to the Ethiopian canon is the Book of Jubilees. As the Encyclopedia of the Bible explains, Jubilees is also known as Little Genesis, because it is a retelling of the events of the canonical book of Genesis and the beginning of Exodus. It does, somewhat ironically, add more details, thereby actually making it bigger than Genesis. The book has marked contradictions with the theology of both the Old and New Testaments, which probably contributed significantly to its exclusion from most canons.