The Tragic Reason Aurochs Went Extinct

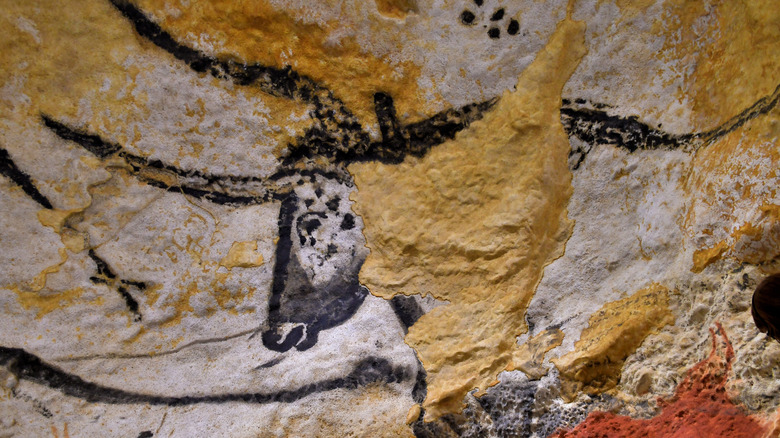

For thousands of years, large herds of aurochs, the ancestors of modern cattle, roamed throughout Europe, North Africa, and Asia. The males, standing nearly 6-feet tall at the shoulder and weighing more than 2,200 pounds, had massive curved horns more than 40 inches long. They weren't just burly but fast and agile as well, allowing them to fight off most predators. Except for one: humans. Paleolithic cave paintings, including those at Lascaux, France (see one above), depict these creatures that were once hunted extensively for food during that period. Still, they lived on.

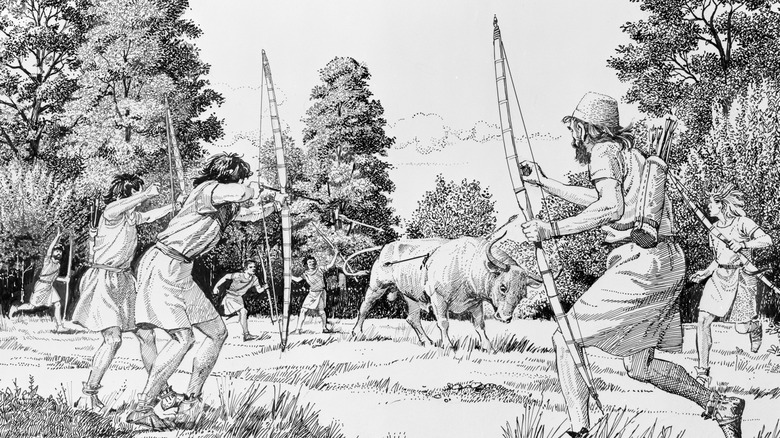

Around 58 B.C., the Roman emperor Julius Caesar wrote about them. He described them as being "a little below" the size of the extinct North African elephant and very powerful. "Their strength and speed are extraordinary; they spare neither man nor wild beast which they have espied," he wrote (via "On the Origin of Cattle: How Aurochs Became Domestic and Colonized the World"). Caesar also praised the hunting of these majestic animals, which were also used for sport in Roman amphitheaters.

It was ultimately humans that led to their eventual end. Like the bison of America's Great Plains, aurochs were once so plentiful that no one even considered they might go extinct. But unlike bison, which were saved from the brink by early conservation efforts, the species died out by the 17th century. Hunting, along with things like the systematic destruction of the aurochs' habitat, were the main culprits.

The last aurochs died in 1627

Like passenger pigeons, which also went extinct, aurochs would eventually join a long list of other animals, from dodos to the Tasmanian tiger, that died out due to humans. In the case of aurochs, which first appeared around 700,000 years ago in what is now Tunisia, habitat loss played a major role in their demise. And part of that was due to competition from domesticated cattle that humans had begun breeding from wild aurochs around 10,000 years ago. The diseases passed from domesticated cattle to aurochs also took their toll, as did overhunting.

Over the centuries, the auroch's habitat slowly dwindled. Within the first millennium B.C. (1000 B.C. to 1 B.C.), the animals were likely already gone from North Africa, India, China, the Near East, and the British Isles. As grazing land became more valuable, the aurochs were pushed into forests and swamps. The last known herd survived in Poland's Jaktorow Forest under the protection of the Polish Crown. But even so, from 1564 to 1599, the herd went from 38 to 24. And by 1620, the last bull had died, followed by the last cow in 1627 in what was the first extinction to ever be documented.

Are aurochs gone for good?

After nearly 400 years, breeding programs led by two organizations — Rewilding Europe and Grazelands Rewilding — have used a technique called back breeding to create a close proximity of aurochs called tauros (above). While it's not quite de-extinction (bringing animals back) through various means like biotechnology, it's pretty close. The tauros shares more than 99% of its genetic makeup with its ancient ancestor, much more than an earlier attempt in 1920s Germany that resulted in Heck cattle.

It's thanks to a revolution in DNA technology that the tauros came to be. Scientists mapped the genomes of seven breeds of wild cattle and used cross-breeding and other techniques to produce the auroch-like animal. There are currently more than 800 tauros, with herds in Spain, Portugal, Croatia, Czech Republic, Romania, and the Netherlands. Scotland is also in line to get a herd of 15 tauros in 2026. Unlike some other deadly prehistoric animals such as megalodons and Titanoboas, bringing back aurochs, or at least a close proximity, will be beneficial. According to Rewilding Europe, tauros can help restore Europe's grasslands and forests. While humans helped kill off the aurochs, they are now doing their best to bring them back.