The Tragic Real Life Story Of Annie Oakley

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

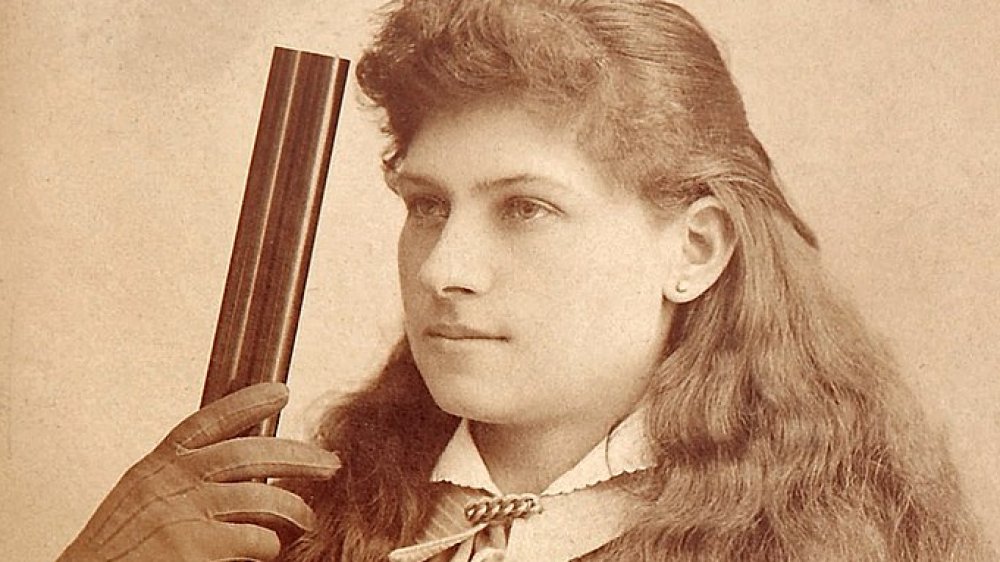

In the 1880s, stories of Annie Oakley's incredible shooting talents spread like wildfire. In a time when many women were confined to their homes and families, Oakley overcame a horrible childhood to go against a challenging man's world—and win. Her achievements earned her a permanent place in history. (Ironically enough, one of the West's best known celebrities never crossed the Mississippi until she was well into her career.)

Oakley did more than just become America's shooting sweetheart. Born poor, abused and starved as a child, and forced to fend for her family, Oakley overcame amazingly huge obstacles to earn her celebrity status. In her time, there was no department of social services to help her. The girl was forced to depend solely upon her own wits and shooting skills for survival. Over time she learned to read and write and gained the social etiquette she needed as she met the rich and famous throughout her career. Little did she know at the time that by the end of her life, she would be revered all over the country. Everyone marveled at the girl who could hit her mark every single time. When asked how she did it, Oakley advised, "Aim at a high mark and you'll hit it. No, not the first time, nor the second time. Maybe not the third. But keep on aiming and keep on shooting, for only practice will make you perfect."

Annie Oakley was born Phoebe Ann Mosey ... or was it Moses?

Just who was Annie Oakley? She was born on August 13, 1860 in a rundown cabin near Greenville, Ohio. According to the Annie Oakley Center Foundation, although Annie said her family's last name was Mosey, her brother John claimed the name was Moses. Historical documents on the family show both names, so no one is actually sure what she was called at the start of her life.

They do know Annie's family was poor. Her father, Jacob, died when Annie was only 5-years-old. According to Annie's great-grand niece, Bess Edwards, Jacob was on his way to town to buy supplies and take the family's crops to a mill during the winter of 1865 when he was caught in a blizzard and died.

Left with several children to feed, Annie's mother, Susan, became even more impoverished. The large family tried moving to a smaller home, where Susan instilled her Quaker values on the children, remarried, and even worked as a domestic nurse for $1.25 per week. It wasn't enough. As a way to lighten her load in about 1868, Susan finally accepted offers to "farm out" some of the children, a common way for poor families to give their children good homes by letting them live with others. A Mrs. Edington, whose husband Frank was superintendent of the local poor farm, offered to house Annie and teach her domestic skills. In turn, Annie would sew for the family and look after the younger children at the facility. Susan accepted.

'He-Wolf' and 'She-Wolf' abused Annie Oakley

Three weeks after her arrival at the poor farm, Oakley was sent to live with a family who was so cruel that she forever after referred to them as "He-Wolf" and "She-Wolf." Her tormentors might have been Abram and Elizabeth Boose, with whom Oakley lived in 1870. "He-Wolf" promised the girl's only job would be looking after an infant, but that was not the case. Instead, Oakley's workday began at 4 a.m. and consisted not only of caring for the baby, but also preparing meals, caring for livestock, maintaining the garden and hunting for food. She was beaten, starved, and perhaps, according to writer Carolyn Gage, sexually abused. When Susan Mosey sent for her daughter, she was told Oakley was attending school and was quite happy.

One evening, Oakley remembered, after she fell asleep while sewing, "the 'She-Wolf' struck me across the ears, pinched my arms and threw me out of doors into the deep snow and locked the door." Oakley feared she would freeze to death and fell to her knees to pray, but said, "my lips were frozen stiff and there was no sound." The girl finally escaped in 1872 with no money, but a kind stranger fed her and bought her a train ticket home. Once there, Oakley alternated her time between her mother's home and some friends named Shaw. She also began attending school. One day, "He-Wolf" showed up at her classroom. Frank Edington intervened, and the man never returned.

Annie Oakley started out shooting for survival

Annie Oakley's homecoming was not the end of her troubles. Susan Mosey had remarried and bore another child, but her husband died. According to Encyclopedia.com, Mosey married yet again, but husband number three was going blind. The family was close to losing their farm. Fortunately, Oakley already knew how to hunt. She later remembered steadying her father's muzzle rifle on the porch rail at the age of eight, and shooting a squirrel cleanly through the head—the best way to preserve the meat. "I still consider it one of the best shots I ever made," she would later say. Now, Oakley hunted to feed her family. Her shooting skills improved dramatically, and before long she could soon shoot with either hand and began learning impressive trick shots.

Oakley also worked on her reading and writing, as well as her sewing skills. Carolyn Gage wrote that Oakley's family remembered her being obsessed with routine, carrying out a stringent daily schedule—probably her way of dealing with her abusive past. But her work paid off. Her shooting skills not supplied her family with food, but she also sold game to Greenville merchants for use in restaurants and hotels around the state. Within three years she made enough money to pay off the family farm. "Oh, how my heart leaped with joy as I handed the money to mother and told her that I had saved enough to pay it off!" she later recalled.

Annie Oakley's shooting match made in heaven

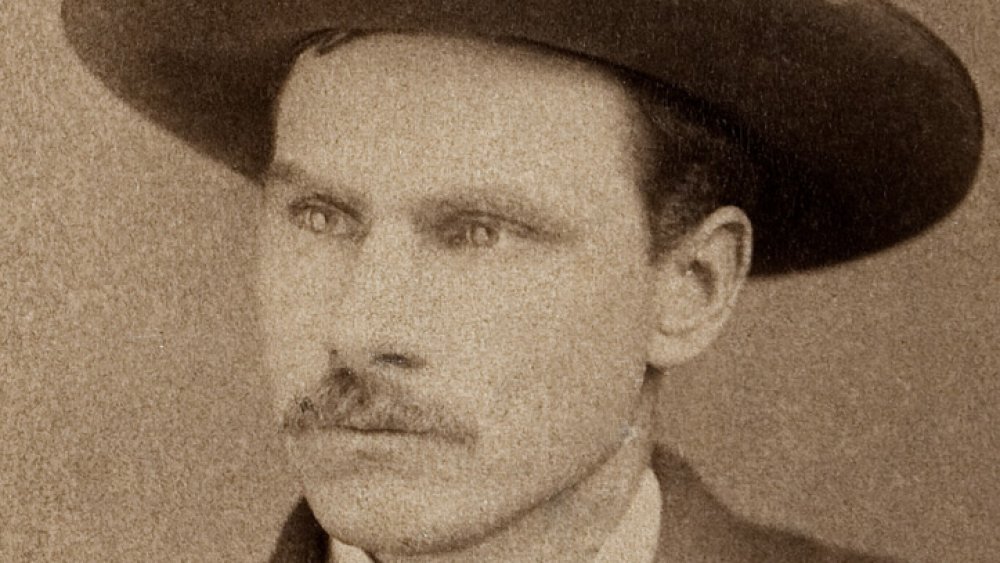

Annie Oakley was only 15-years-old when she paid off her family's farm. News of her remarkable expertise with firearms began to spread. According to the Annie Oakley Center Foundation, on an 1875 visit to Cincinnati to see her sister, Lydia, Oakley was approached by hotel owner Jack Frost. A shooting contest was taking place, and Frost invited Oakley to compete against a professional entertainment and trick shooter, Frank E. Butler. The amused Butler actually chuckled at the site of the petite little lady who came up against him, and offered to take all bets with a purse of $100. But Oakley had the last laugh, hitting all 25 clay pigeons as they sailed into the air. Butler hit only 24.

Butler was impressed, to say the least. "Right then and there I decided if I could get that girl I would do it," he later said. Indeed, Butler was smitten, meeting his match in the beautiful, serious-minded Oakley. He made it his mission to get to know the girl better, and wormed his way into her heart via George, the French poodle whom he used in his acts. Oakley became very fond of George. Butler, himself 10 years older than Oakley and a divorcee with two daughters, began sending her letters expressing his love for her. But the letters were always "signed" by the dog. The ploy worked, and the couple is believed to have married on August 23, 1876 in Cincinnati.

Annie Oakley joins Buffalo Bill's Wild West show

The Butlers began traveling around the west, but Annie Oakley didn't actually perform with Butler until 1882 after his regular partner fell ill. She adopted her stage name after a Cincinnati neighborhood. In her biography of Oakley, author Shirl Kasper confirmed the woman's amazing feats: She could shoot dimes from a man's hand and cigarettes from his lips, hit the flame on a moving candle, and shoot the middle of the Ace of Spades over her shoulder using a mirror. In one act, four balls were catapulted into the air as Annie ran to vault over a table and shoot each ball before it hit the ground. She could also shoot targets while standing on the back of a galloping steed.

In 1885, William "Buffalo Bill" Cody offered the Butlers a three-day trial run with his "Buffalo Bill's Wild West" show. Cody was duly impressed, and immediately hired the couple. He called Oakley "Li'l Miss" and scheduled her as one of his first acts, to get the crowd used to the sound of gunfire. The show embarked on a tour of the U.S., and would eventually travel to England. One of Oakley's show mates, Chief Sitting Bull, was so impressed with her that he sent her $65 for an autographed photo. Oakley returned the money, with the requested photo. Sitting Bull christened her "Watanya Cicilla," which others translated to mean "Little Sure Shot."

Annie Oakley's show was fit for a queen

In 1887, Buffalo Bill's show boarded a steamship in New York bound for England. The troupe had been procured to perform during Queen Victoria's 50th Anniversary Jubilee. Aboard the ship, according to Historynet, were "cowboys, sharpshooters, musicians, and 97 American Indians, plus 180 horses, 18 buffalo, 10 elk, 10 mules, five Texas steers, and the old Deadwood stagecoach." The group survived a wicked storm which made nearly everyone, except Oakley, seasick. Upon their arrival, some 200 performers appeared in the show on May 9 in London. The crowd was mesmerized as the troupe simulated Indian wars and Annie shot a cigar from Frank Butler's mouth.

The queen apparently read the rave reviews and heard of the exciting exhibition, for she requested Buffalo Bill to give her a private show "by royal command." Cody was glad to oblige, and the troupe repeated their performance before her majesty and 25 others. Afterwards, Queen Victoria not only stood and bowed before the American flag, but she also requested to meet the performers. She was especially enamored with Oakley, who remembered that "she asked me when I was born, at what age I took up shooting and several other questions." When Oakley finished answering, Queen Victoria told her, "You are a very, very clever little girl." Oakley was enthralled, even more so when the queen gave her several horses as a gift before the show traveled back to America.

Annie Oakley indirectly helped women's lib

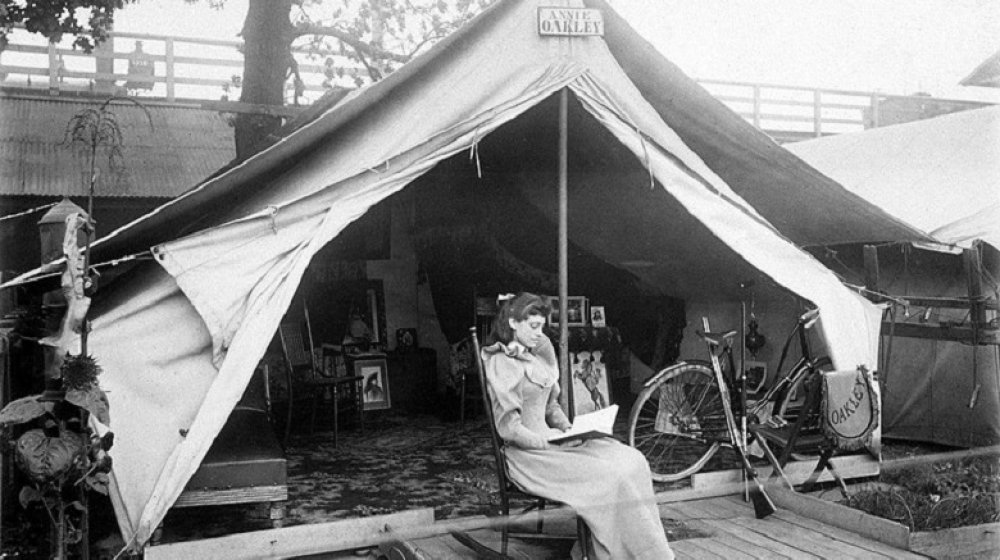

Her shooting talents aside, something else made Annie Oakley most unique in 19th century America: The lady wore knee-length costumes as her chestnut hair flowed down her back—two no-no's for feminine dress of the day. In her thesis, "Annie Oakley, Gender, and Guns," Sarah Russell theorizes that Oakley's blending of short dresses with leather and fringe was initially accepted since the costumes jived with clothing worn by younger generations. Another thesis, this one by Julie E. Williams, rightfully supposes that Oakley got away with her wardrobe because she maintained the lifestyle of "a feminine, domestic, and virtuous woman." Unlike others working for Buffalo Bill who enjoyed a good party, Oakley preferred the comfort of her tent between shows, reading her Bible and sewing.

Annie Oakley's career also encouraged more women to participate in sports, a pastime normally dominated by men. There is a chance, too, that Annie recognized her advantage as the picture of the new modern woman even as she declined to participate in women's movements. In 1898, she brazenly penned a letter to President William McKinley as the Spanish-American War loomed on the horizon. In it, Oakley volunteered her services by offering to personally organize and train 50 female sharpshooters to serve, should America officially go to war. The women would come with their own ammo and arms. Her request was denied, largely because at that time women were not permitted to serve in the military.

Tragedy on the train

By 1901, Annie Oakley was at the top of her game. The Wild West show was famous across America, traveling from town to town and giving well-attended performances. But the show came to a grueling stop in North Carolina with a horrific train wreck on the early morning of October 29, 1901. In an article about the tragedy, writer Walter Boyd pointed the finger at railroad engineer Frank Lynch, who didn't understand that there were three, not just one, trains carrying the performers, equipment, and animals from the show. At about 3:20 a.m., Lynch's train failed to yield to the second train in the convoy, slamming into it with deadly force. Annie Oakley's private car was on the back of the train, which also contained the animals for the show.

Several people were badly injured, and over 100 horses were killed in the wreck—including those given to Oakley by Queen Victoria and William Cody's own horse, Pap. Cody "broke down utterly at the grievous sight" and went after Lynch with a shotgun, but the man had already fled. Oakley, who was sleeping when the accident occurred, was violently thrown from her bunk and remained in a coma for 17 hours. When she awoke, her left side was paralyzed. They say her hair turned gray during the five surgeries, months of recovery, and two years before she would walk again. In the aftermath, souvenir hunters would report finding items from the wreck for weeks.

Annie Oakley and World War I

Annie Oakley's time with Buffalo Bill's Wild West show was done. Needing a less strenuous career, she turned to acting, appearing in a play titled The Western Girl beginning in 1902. The script was written just for her: Oakley's character, Nancy Berry, was portrayed as a brave, rootin' and tootin' gal who outfoxes a group of Wild West outlaws with a pistol, rifle and rope. HistoryNet confirms that Oakley's hair was now white, requiring her to wear a wig. She also began giving shooting lessons for exclusive gun clubs. Frank Butler, meanwhile, took a job with the Union Metallic Cartridge Company. The position required giving demonstrations, allowing the couple to continue giving shooting exhibitions to illustrate how great the products were. Without his star performer, however, Buffalo Bill found it harder to draw crowds. The show filed for bankruptcy in 1913.

When World War I broke out, Annie Oakley again tried her luck at offering to give shooting lessons to the troops. She was again denied. According to authors Katherine H. Adams and Michael L. Keene, however, Oakley took matters into her own hands instead and traveled across America, giving shooting lessons and demonstrations for the National War Council of the Young Men's Christian Association, as well as the War Camp Community Service. In 1922, she was back in North Carolina when, at the ripe age of 62 years, she hit 100 clay targets in a row from 16 yards away.

Love until the end

In November of 1922, the Butlers were vacationing in Florida when another car forced their vehicle off the road. According to author Brenda Haugen, Annie was pinned underneath the car, breaking her hip and shattering her ankle. For six weeks, faithful Frank rented a room across from the hospital as his wife recovered. Then, in 1923, the Butler's beloved dog Dave was fatally hit by a car. The couple was devastated, for Dave was not only their pet but also had performed with them. By the fall of 1926, the Butlers were in Ohio when Annie encouraged Frank to attend a shooting match in New Jersey. The couple planned to spend the winter in North Carolina, but Frank became so ill that his relatives in Michigan took him to their home instead.

Annie, meanwhile, realized her own health was failing and moved back to Greenville. She also planned her own funeral, specifically requesting a female embalmer—perhaps due to her earlier abuse by "He-Wolf." On November 3, Annie died in her sleep at the age of 66 years. Frank was brokenhearted and stopped eating, dying just over two weeks later. America mourned the loss of the couple, especially Annie, whom Will Rogers called "a greater character than she was a rifle shot." Her longtime friend, Fred Stone, talked about her in his autobiography in later years. "There was never a sweeter, gentler, more lovable woman," he said, "than Annie Oakley."

Annie Oakley brought to life

When Annie Oakley died, Americans lost their heroine. Fans would never forget the little lady who aimed to please them. Fortunately, two films—one produced in 1894 and another in 1900—survive in which the famed shooting champion demonstrated her skills. In the years after Oakley's death, movies, a television show, and even songs fictionalized her life. The first film of her life, aptly titled Annie Oakley, came out in 1935 and starred Barbara Stanwyck. A musical, Annie Get Your Gun, starring Ethel Merman premiered in 1947, and was then made into a 1950 movie starring Betty Hutton, and would be remade in 1957.

Between 1954 and 1957 a television show, also titled Annie Oakley, ran in syndication. But the show was pure fiction, with Oakley and her brother keeping order in the town of Diablo while the girl flirted with the sheriff. One thing is for sure: Annie Oakley was, and still is, revered as a feminist before her time, a woman who was not afraid to show off her hard-earned skills. She blossomed as a modest symbol of the American female spirit, in a time when most women were relegated to careers as housewives and domestic workers. "I would like to see every woman know how to handle guns," she once said, "as naturally as they know how to handle babies." Most importantly, Annie Oakley's endurance and strength in the face of tragedy remains something to be admired, even today.