What The Final Year Of MLK Jr.'s Life Was Like

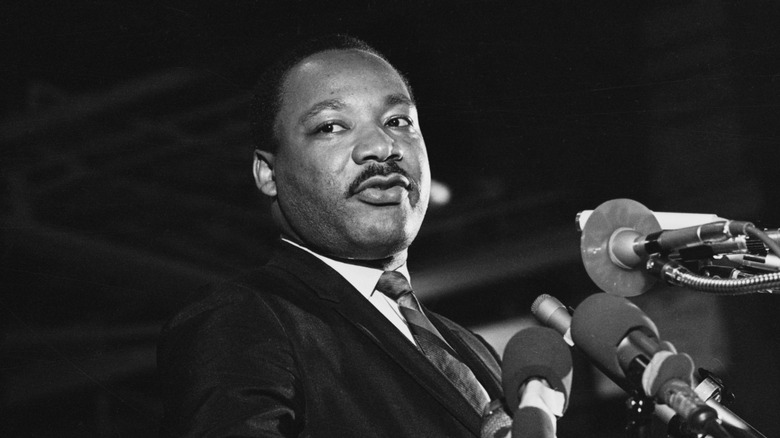

Today, the life of Martin Luther King Jr. is retold so often and in so many different ways that he may start to seem like a distant mythical figure. Of course, he wasn't. King was very much a human being — one who undertook history-making work, to be sure, but also one who reacted to the stresses of his position in a decidedly human way. Perhaps that is most clear in the final year of his life, from the spring of 1967 until his assassination in Memphis, Tennessee on April 4, 1968.

In those 12 months, King continued his civil rights work while also adding broader goals that he argued were connected to his by-then famous work to achieve racial equality. Most notably, he began to speak out against the Vietnam War and took his first steps to organize an advocacy campaign for low-income Americans. But while some heartily applauded these new efforts, others remained skeptical. Some even began to question if King's adherence to nonviolence and willingness to work with establishment figures like President Lyndon B. Johnson was undermining the movement.

With the rise of Black separatist speakers like Malcolm X and the more militant Black Power movement, it clearly seemed that way to some. By 1967, with the country still mired in civil strife and then taking part in a bloody and controversial war, King was a complicated figure for many Americans. His final year would only underline the intensity of his position.

He became overtly anti-war

While the bulk of Martin Luther King Jr.'s work — and his legacy — centered on civil rights activism, the final year of his life was marked by more obvious anti-war statements. Perhaps it shouldn't have been entirely shocking, as he was widely known for his nonviolent stance and had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964. Even so, King's outright critique of the Vietnam War was, for some, surprising. Though many were pleased by his stance, others were rankled, including some of his longtime supporters. This change came with his speech, "Beyond Vietnam — A Time to Break Silence," delivered at New York City's Riverside Church on April 4, 1967, a year to the day before his assassination. To the assembled crowd, he said that his conscience could no longer allow him to be silent, though he had already encountered resistance to the idea that he would stray out of his civil rights lane.

While acknowledging the complexity of the war, King also said that he ought to have "first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today — my own government." Going on, he said that "if America's soul becomes totally poisoned, part of the autopsy must read: Vietnam." After describing the effects of war and of growing fear and hatred on seemingly all sides, he called for a ceasefire. "We still have a choice today: nonviolent coexistence or violent coannihilation," he said in his concluding statements. "We must move past indecision to action."

He came into conflict with LBJ

There was one ally in particular who was greatly aggrieved by Martin Luther King Jr.'s anti-war stance: Lyndon B. Johnson. The U.S. president was once a major supporter of MLK, though much of their collaboration remained behind the scenes as Johnson helped to push through the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Publicly, Johnson said that civil rights legislation would be one of the best ways to honor the recently-assassinated President John F. Kennedy. Behind closed doors, he regularly communicated with King, though supporters on both sides viewed the other with trepidation. It didn't help that FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover was actively working to undermine King on the assumption that the civil rights leader was a secret communist.

But King's new, more public stance against the Vietnam War placed a significant roadblock on his path with LBJ. He last spoke to President Johnson in 1966 in a phone call in which he discussed Vietnam. King proceeded to ghost the president, canceling at least two meetings before his "Beyond Vietnam" speech with no explanation.

Johnson was reportedly taken aback and allowed the FBI to give reporters information about King's ties to lawyer Stanley Levison, who the FBI had connected to the Communist Party of the United States of America. Whatever the truth of this relationship, the one between MLK and LBJ further soured when King publicly announced he wouldn't support the politician's 1968 bid for the presidency (Johnson later declined to seek reelection anyway).

MLK found himself stuck in the middle

While Martin Luther King Jr. was no stranger to controversy, his other causes made some supporters uncomfortable — if not outright angry. For those on the left, it felt as if King wasn't pushing hard enough for change. His nonviolent tactics and willingness to cooperate appeared to be a sign of milquetoast morals and capitulation to those in power. For more conservative Americans, King's disavowal of the war in Vietnam — not to mention his eye-opening argument that America would lose its soul — was also troubling. Was he really an anti-American communist, after all? Even if others thought this notion was alarmist, they expressed concern that King was essentially straying out of his lane. To their minds, anti-war advocacy distracted from the original goal of achieving racial equality. The New York Times published an editorial baldly titled "Dr. King's Error" that said just that, further arguing that King's attempt to link the controversial war to inequality back home wasn't well-supported.

Reader responses only illustrated the mixed reaction. Some critiqued the NYT for trying to dissociate complex issues that were indeed linked, while others made it clear that King calling the U.S. out for violence in the war was a step too far. All told, it was painfully obvious that King's standing had taken a serious hit by this decade. A 1966 Gallup poll indicated that 63% of Americans disapproved of him, in stark contrast to his more glowing reputation today.

King turned to low-income advocacy

In his "Beyond Vietnam" speech, Martin Luther King Jr. not only spoke out against the Vietnam War but also noted how poverty came into play. He referenced LBJ's War on Poverty, part of the president's Great Society effort that included the first Head Start education programs and the beginnings of Medicare and Medicaid for seniors and low-income Americans. Yet the Vietnam War pushed LBJ to reroute funding away from the War on Poverty.

MLK said in his April 1967 speech that, after the U.S. entry into Vietnam, "I watched this program broken and eviscerated, as if it were some idle political plaything of a society gone mad on war." Furthermore, King said, the war was disproportionately affecting poor and Black Americans, who were tasked "to fight and to die in extraordinarily high proportions relative to the rest of the population." By 1965, though they comprised about 12% of the U.S. population, Black Americans made up 31% of combat troops in Vietnam and 24% of combat casualties (per the Library of Congress).

While King had practically nothing to do with on-the-ground efforts in Vietnam, in the final year of his life, he did make his first steps to address poverty on American soil. In November 1967, he announced to staff of his Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) that the organization would undertake what he termed the "Poor People's Campaign." The idea was to gather about 2,000 low-income people of many different communities together for a march in Washington, D.C. However, King wasn't able to advance the Poor People's Campaign much before his April 1968 assassination.

He was still being actively investigated by the FBI

J. Edgar Hoover was not exactly in the business of making friends. By the 1960s, he had established himself not just as the head of the FBI but also as one of the nation's leading anti-communist crusaders. Hoover used the surveillance network of the agency to amass files on people he deemed a potential threat. Seemingly anyone who was an artist, activist, or progressive political figure was under the watchful eye of him and his team. It is little surprise then to learn that Martin Luther King Jr. was sometimes a target of Hoover's personal ire.

The FBI grew increasingly interested in King throughout the 1960s, to the point where then-Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy authorized wiretaps of King's home and offices. Though no real evidence of MLK being a secret communist emerged, the FBI did collect documentation that King was unfaithful to his wife, Coretta. The mission apparently shifted to discrediting and demoralizing King, a move that included sending an anonymous letter to the civil rights leader allegedly urging him to die by suicide.

The point was apparently to make King a less-than-appealing target for recruiting communists, but that confusing point remains speculative. Though the wiretaps stopped by 1965, Hoover and the FBI never fully gave up their surveillance of King. Certainly, by 1967 and 1968, King and his associates were well aware that he was being watched by the FBI, having rightfully assumed that the menacing letter originated from someone at the agency.

His take on communism became more complicated

Regardless of what FBI director J. Edgar Hoover might have thought, Martin Luther King Jr. was no communist. He had even made a point to say that communism was incompatible with his Christian faith. Though he'd been speaking on the subject since the 1950s, a 1962 speech, "Can a Christian be a Communist?", was one of the more obvious statements of King's skepticism on the matter. Calling it "the only serious rival of Christianity," he argued that it was nothing short of evil.

That isn't to say that King was an avowed capitalist. In fact, some argue that he may be most rightfully considered a Christian socialist, with statements indicating that he thought wealth and power ought to be shared amongst all Americans. But, perhaps because of the social and political climate of the time, it wasn't until the final years of his life that he started to use words like "socialism" in his speeches (by the 1950s, he had privately admitted to sympathising with Marxism and other forms of socialism).

Toward the end of his life, King's take on communism became more complicated. Though he never signed off on the ideology, he did note that perhaps the United States and Americans in general had become overly afraid of the system. In his "Beyond Vietnam" speech, King referenced America's "morbid fear of communism," which he argued was so intense that it impeded real progress on matters of racial and social justice.

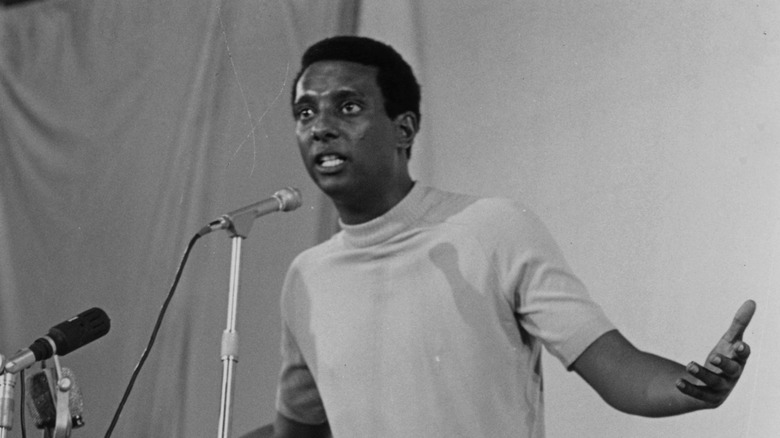

King's nonviolent efforts came into conflict with the Black Power movement

Nonviolence had long been a core principle of Martin Luther King Jr.'s activism. His commitment to it hinged on opposing what he believed were evil ideas, but not the people who held those ideas. King generally argued they were still worthy of compassion.

But as the 1960s wore on, other activists began to push back. In 1964, activist Malcolm X was openly critical of the nonviolence principle. In a speech titled "A Declaration of Independence," he advocated for the immigration of Black Americans to Africa and forcefully denounced the idea that MLK Jr. held dear. "Concerning nonviolence: it is criminal to teach a man not to defend himself when he is the constant victim of brutal attacks," he said. "It is legal and lawful to own a shotgun or a rifle. We believe in obeying the law." Two years later, activist Stokely Carmichael — who while a student was once a proponent of King's nonviolence — publicly began calling for increased "Black power" and moved more closely to Malcolm X's idea of Black separatism. Eventually, the Black Power movement became associated — rightfully or not — with armed violence and groups like the Black Panther Party.

King decried this shift, saying that it indicated a loss of hope for the future and for the peaceful methods he had so long championed. He also expressed dissatisfaction with the idea of pulling away from a larger, more integrated society into closed ranks. Yet while he privately expressed his concerns, he never publicly criticized the movement.

MLK had one more meeting with Thich Nhat Hanh

Martin Luther King Jr. worked closely with Thich Nhat Hanh, a Zen Buddhist monk and peace activist. By the 1960s, Thich Nhat Hanh had both taken direct action to aid those in South Vietnam and begun writing and speaking in opposition to the Vietnam War. Facing accusations that he was a communist, Thich Nhat Hanh was exiled from Vietnam in 1973. It wasn't until 2005 that he was finally allowed to return. He spent the intervening decades gaining worldwide renown as an activist, writer, speaker, and Buddhist teacher.

In 1965, Thich Nhat Hanh reached out to King for help opposing the Vietnam War. They met in person in June 1966 in Chicago. By January 1967, King wrote to the Norwegian Nobel Committee to nominate Thich Nhat Hanh for the Nobel Peace Prize (the prize was not awarded to anyone that year). In his letter, King referenced his own 1964 Nobel Peace Prize and spoke glowingly of Thich Nhat Hanh not only as a personal friend but also as a pioneer in peace activism who was brave enough to speak out against war despite the harsh reaction that followed.

The two met one more time, at the May 1967 Pacem in Terris conference in Geneva, Switzerland. Sharing breakfast together, Thich Nhat Hanh told King that in Vietnam, he was widely considered "a bodhisattva." Per the Thich Nhat Hanh Foundation, the Buddhist explained that this is "an enlightened being trying to awaken other living beings and help them go in the direction of compassion and understanding."

He experienced mental health issues

After many years of civil rights activism and oftentimes violent pushback, Martin Luther King Jr. was tired. In the final months of his life, some believed that his speeches were marked by a fatigued affect. Perhaps weighed down by years of violent threats, skepticism from all corners, one assassination attempt in 1958, and what must have seemed like a long road ahead to anything even approaching true equality, he was understandably at a low point. "I'm frankly tired of marching, I'm tired of going to jail," King said, though he followed by saying his faith gave him the energy to continue (via Britannica).

But were more pervasive struggles with mental health coming into play? Certainly, if King had ever been officially diagnosed with a mental illness, the attack-ready J. Edgar Hoover would have found something. Though nothing of the sort came to light, the line between bowing under immense pressure and dealing with a disorder like depression is very fine indeed. There are suggestions that, on top of everything else, King may have had to consider his mental health more deeply in 1967 and 1968. He apparently experienced bouts of severe depression throughout his life and, while just 12 years old, reportedly attempted to die by suicide after learning of his beloved grandmother's death. Still, some caution that attempting to pathologize Martin Luther King Jr. could all too easily undermine the complexity of his life and mission.

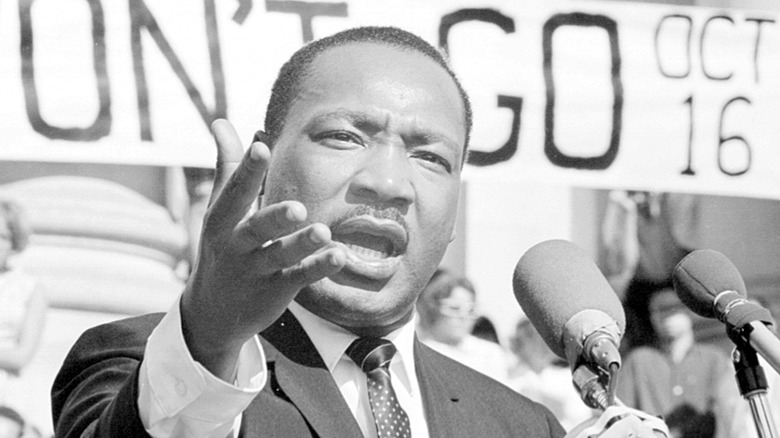

A march in early 1968 went wrong

In the first months of 1968, a march organized by Martin Luther King Jr. went decidedly off the rails. It centered on Memphis, Tennessee, where Black sanitation workers had begun a strike in February. Activists there had already done much to highlight the low pay and dangerous work faced by the strikers (two had been fatally crushed by garbage compactors on February 1). King arrived to lend his support and organize a march, but SCLC staff were reluctant to divert resources away from the Poor People's Campaign. Still, King went at the behest of Memphis organizers.

King started strong with a speech delivered to some 14,000 people, in which he referenced the labor issues he saw at play. But on March 28, a protest march led by King went wrong. Some participants began breaking windows and looting, police moved in with tear gas, the activist was hurried away, multiple people were injured, and one was shot to death. King, who was shaken by the incident, faced accusations that other planned marches would turn to similar violence. Less than a week later, King returned to Memphis to lead another march and hopefully redeem the principles of nonviolent protest. In the meantime, city leaders sought a federal injunction to stop another march.

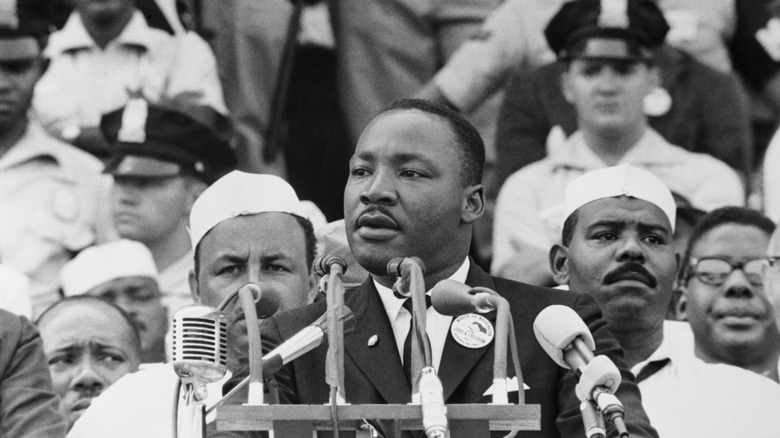

He responded to violent protests in his final speech

The last speech given by Martin Luther King Jr., now known as "I've Been to the Mountaintop," clearly reflected the hope and fatigue that battled within the civil rights leader. Delivered just one day before his assassination in Memphis, Tennessee, he addressed a crowd at the city's Bishop Charles Mason Temple. Though he had to be persuaded to speak by his fellow activist Ralph Abernathy, the speech proved powerful and remains one of his most often-quoted. Speaking of the massive social and political changes he had seen, King told the crowd (via American Rhetoric): "It is no longer a choice between violence and nonviolence in this world; it's nonviolence or nonexistence. That is where we are today."

More directly, he referenced the infighting that he had so often experienced directly and the unrest that had marked not just the many years before, but the disastrous march weeks earlier. "We've got to stay together and maintain unity," he said. "You know, whenever Pharaoh wanted to prolong the period of slavery in Egypt, he had a favorite, favorite formula for doing it. What was that? He kept the slaves fighting among themselves. But whenever the slaves get together, something happens in Pharaoh's court, and he cannot hold the slaves in slavery."

He was also openly contentious of the injunctions Memphis city officials had sought against another march. Whether or not such a legal action would be approved by a federal judge was of no consequence to him, King maintained. "But somewhere I read of the freedom of assembly," he proclaimed. "Somewhere I read of the freedom of speech."

King indicated that he expected death, and soon

Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I've Been to the Mountaintop Speech" wasn't merely defiant. Neither was it the expression of a man who had reached the limit of his endurance. Yet King did express a sense of his own mortality that became eerily prophetic less than 24 hours later.

The mountaintop and promised land referenced in the speech are a clear callback to Moses, who spoke to God atop Mount Sinai in the Book of Exodus. Later, in Deuteronomy, God grew displeased enough with Moses that he wouldn't let the prophet enter the longed-for promised land, but he did allow the leader to gaze upon it from Mount Nebo before his death. King told the crowd that night that he had metaphorically seen the promised land — a truly equal society — but that "I may not get there with you."

"Like anybody, I would like to live a long life," King said in his closing statements. "Longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now. [...] And so I'm happy tonight. I'm not worried about anything. I'm not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord." It seems uncanny now that he was assassinated the very next day while standing on the balcony of his hotel. But the bevy of violent threats already levied against King and the high tension of the nation were clearly on his mind that night, and they shaped his resounding speech.