The Hidden Truth Of Cat Stevens

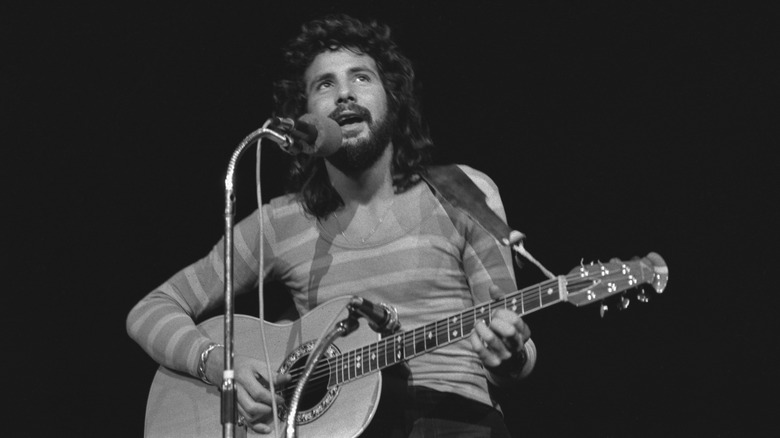

British musician Cat Stevens was at the forefront of the singer-songwriter boom, setting the template with his seminal 1970 album "Tea for the Tillerman," followed by the 1971 classic "Teaser and the Firecat." Those two albums alone would be enough to cement his musical legacy, responsible for such beloved songs as "Wild World," "Morning Has Broken," "The Wind," "Peace Train," and "Moonshadow."

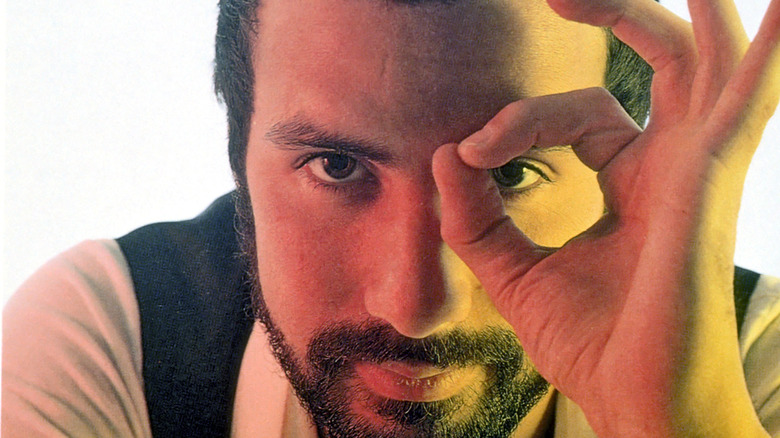

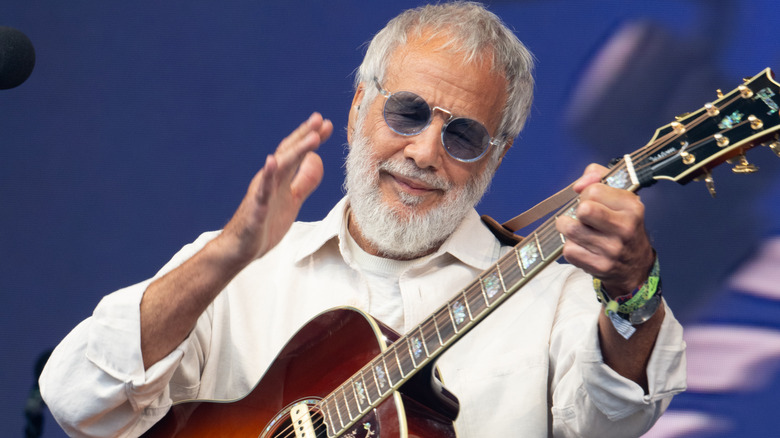

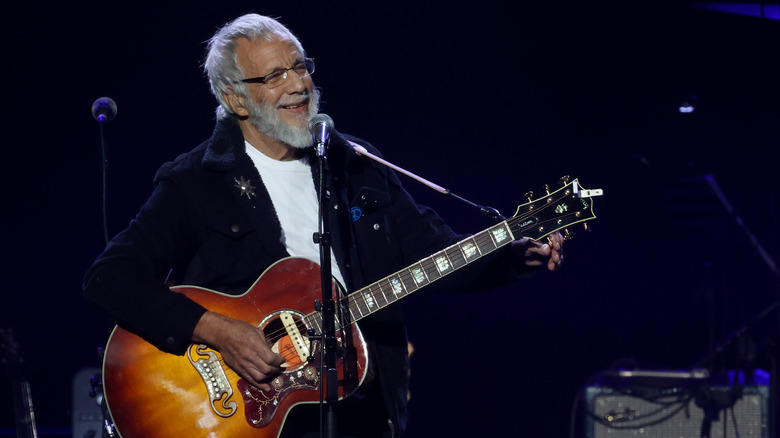

These days, he's known as Yusuf Cat Stevens, following a conversion to Islam that led him to change his name, initially to Yusuf Islam, and slam the brakes on what to that point had been a skyrocketing music career. After more than a decade of focusing his efforts on Muslim education and charities, he re-emerged with new music in the mid-1990s, eventually calling himself simply Yusuf before rebranding with his current moniker.

Throughout it all, Stevens has remained a restless, mercurial figure. There have been moments of triumph and tragedy in Stevens' life, but throughout it all he has maintained his brilliance. Despite his decades of fame, he's also become somewhat enigmatic, with plenty of hidden truths about Stevens remaining unknown to the average fan.

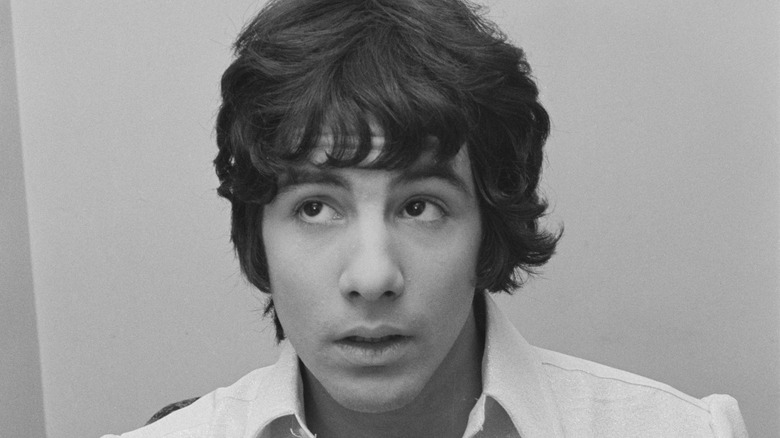

A unique upbringing prepared Cat Stevens to be an observer of life

To describe Cat Stevens' heritage as eclectic is like pointing out the Pope is Catholic. He was born Stephen Demetre Georgiou and his father, Stavros Georgiou, was a Greek Cypriot who'd immigrated to England and whose ethnic heritage blended Greek and Turkish. His mother, Ingrid Wickman, also descended from Greek Cypriots, but was born and raised in Sweden.

"In retrospect I did have an unusual upbringing," Stevens recalled in a 2020 interview with Record Collector. "I was a cockney kid raised Greek Orthodox and Baptist who then went to St. Joseph's Roman Catholic primary school in Covent Garden, just off Drury Lane," he continued. "It prepared me to take an observer's stance on life because I wasn't quite anything; I was a lot of things."

That sense of not belonging to any particular group also fostered an inherent loneliness within him. "I was brought up close to Soho but really I was isolated from both the English and the Greek community," he told Melody Maker (via Majicat) in 1975. "Our family was totally an island."

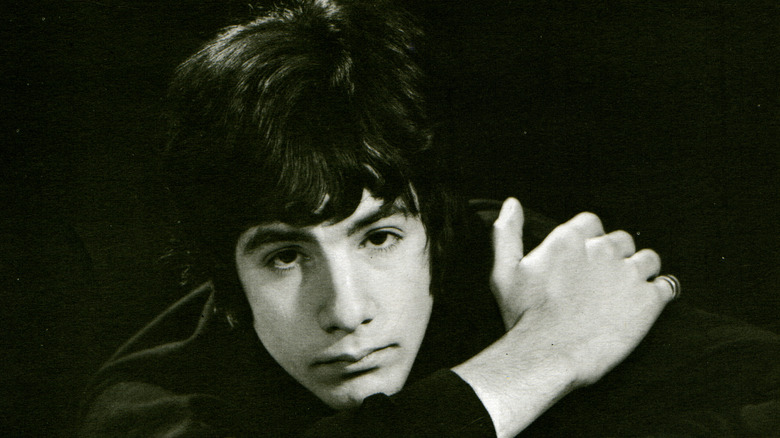

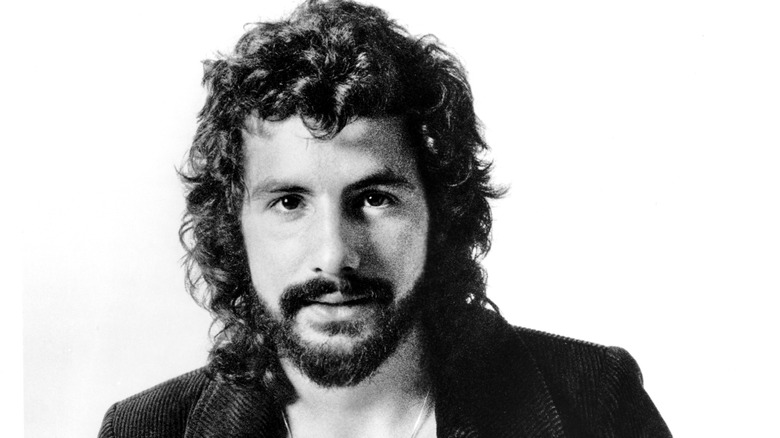

His stage name was inspired by his cat-like eyes

Born Stephen Demetre Georgiou, the origin of Cat Stevens' better-known name dates back to his first steps into the music industry, when he was still a teenager. According to Record Collector, his sister's friend suggested what would become his stage name when she told him, "You've got eyes like a cat." He decided to call himself Cat, with a variation of his first name as his new surname.

For an aspiring pop star, Cat Stevens simply made more sense than the name he was born with. "I didn't think anybody was interested. And I thought that it had nothing to do with me," he explained in an interview with Salon. "I couldn't imagine anyone going to the record store and asking for that Stephen Demetri Georgiou album."

There was another reason why he believed his new name would increase his popularity in the music world. "And in England, and I was sure in America, they loved animals," he added.

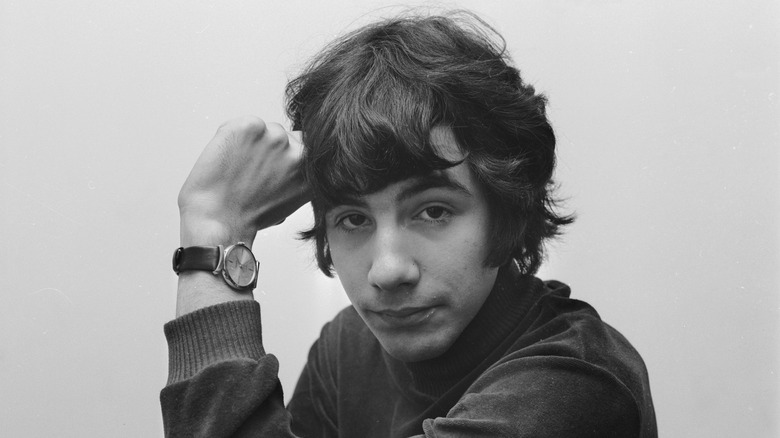

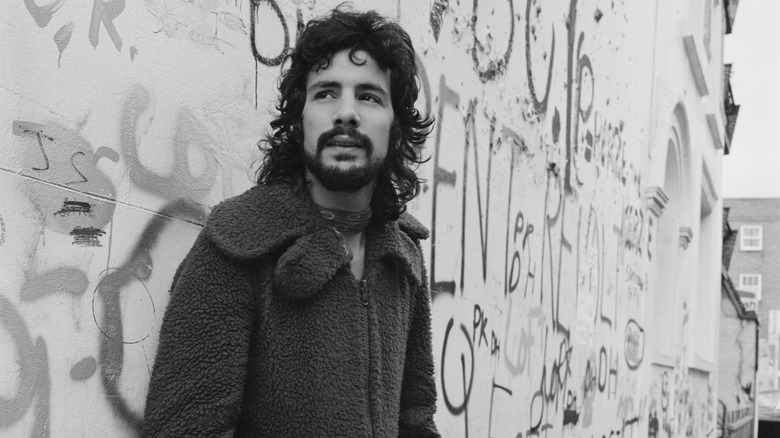

Cat Stevens became a teen idol when he released his first single at age 18

The Cat Stevens who burst on the scene in 1970 with "Tea for the Tillerman" was a far cry from the teenaged pop star who first emerged in the mid-1960s. He got his start performing at pubs and coffee houses in London and quickly gained attention as a songwriter. The demos he recorded as a teenager wound up being cut by other artists, such as "Here Comes My Baby," which became a hit for The Tremoloes in 1967, and "The First Cut is the Deepest," first recorded by P.P. Arnold that same year.

Signed to a record deal at age 18, Stevens released his first album in 1967, "Matthew and Son." The lead single, "I Love My Dog," hit No. 28 on the U.K. charts. His label, Decca Records, was keen to market Stevens as a teen idol, and sent him on tour as an opening artist for acts ranging from Engelbert Humperdink to Jimi Hendrix. The legendary guitarist, in fact, became something of a mentor to the young pop singer.

"Oh, he was great," Stevens said of Hendrix when interviewed by Gold Radio, recalling how Hendrix helped him adjust to life on the road. "He was probably my closest friend," Stevens added. "He was basically a sort of quiet, introverted person — probably he was high on a few things ..."

A 1967 single stirred up controversy

While Cat Stevens and controversy would walk hand in hand in the years after he became a Muslim, he first dipped his toe in such waters back in his teen idol days. The cause was a little ditty from his debut album "Matthew and Son," called "I'm Gonna Get Me a Gun." As it happened, the song's lyrics constituted a not-at-all-veiled and chillingly cold-blooded warning to anyone who'd wronged him in the past. "And all those people who put me down / You better get ready to run / 'Cause I'm gonna get me a gun," he sang.

When the song made its debut on "Juke Box Jury," a popular British TV show with teens at the time, one member of the panel excoriated Stevens for glorifying gun violence. That panelist, by the way, was none other than Jimmy Savile, a popular British TV personality who was later exposed as a predatory pedophile who was able to escape justice for over 60 years.

Interviewed by New Musical Express (via Majicat) at the time, Stevens felt that the lyrics had been taken out of context. "Well, I liked the controversy in the beginning but it got hectic, and I don't want anybody to feel bad or brought down nor to entice kids to buy guns," he explained. "In the context of the western musical, the sound wasn't bad — I liked it, but I see now that it was my fault for not explaining the context before it was released."

He came to see a near-fatal bout of tuberculosis as a blessing

Cat Stevens' promising career as a pop sensation came to a screeching halt in 1968, just as it was getting off the ground. That was when the young singer was diagnosed with severe tuberculosis. Not only was he forced off the road, the illness nearly took his life; doctors ordered him to rest up for a full year in order to regain his health. "I was smoking a lot," Stevens told Mojo. "Dope as well but mostly cigarettes. So then along came this disease and I was stuck with it. It was a kind of godsend in a way for me. That period was my blossoming into who I wanted to be."

After months of hospitalization, he spent the next year convalescing, rebuilding his strength and rediscovering himself as an artist, while also making some major lifestyle adjustments. "Getting sick completely changed the course of my life," Stevens explained in an interview with Guitar World.

The time away from the spotlight allowed Stevens to reassess the path he was on and make some serious course corrections. "And so this was a chance for me to break free of the image and to kind of find myself," he said. "And I was looking very, very deeply into my psyche of who I was ... and that spiritual exploration began in the hospital."

Cat Stevens got out of his record deal because he was a minor when it was signed

Cat Stevens' early recordings, prior to his life-changing bout of tuberculosis in 1968, were markedly different from those that came after. Those post-TB albums, beginning with the 1970 duo of "Mona Bone Jakon" and "Tea for the Tillerman," were released on Island Records, while his earlier albums were released by Decca Records, his first label.

Frustrated with the teen-idol approach Decca had taken with his career, he'd had discussions with Chris Blackwell, founder of Island Records. Hearing the music Stevens had been working on, Blackwell was all in on the new musical direction that Stevens wanted to pursue, and offered him a record deal. There was one big problem, however; he was still signed to Decca. Stevens was able to quash his deal, however, due to a legal loophole: he was under 21 when he'd signed the contract, which at the time was considered a minor. Because of that, he was allowed to step out of his contract uncontested.

Unlike the highly controlled environment at Decca, Blackwell gave Stevens creative carte blanche. "Signing to Island Records was the greatest liberating opportunity I ever had in my career, certainly up to that point," Stevens told Guitar World. "It was like: now you can do whatever you want."

Cat Stevens drew the artwork for his most famous albums

Cat Stevens' album covers are distinctive, from the top-hatted street urchin sitting on a curb alongside a fiery red feline on the cover of "Teaser and the Firecat" to the cover of "Tea for the Tillerman," featuring a red-bearded bloke enjoying a cup of tea in the middle of a forest. Those and other of Stevens' album covers have one key element in common: they were hand-drawn by Stevens himself.

That shouldn't be surprising when realizing he'd studied art before becoming enmeshed in music. According to Stevens himself, he'd come to view the process of creating a song as identical to that of painting. "I converted my artistic skills into painting with words and painting with music, you know?" he wrote in a Facebook post. "I still do the same kind of thing but just sonically and with notes and words rather than colors."

He wrote Wild World about his breakup with Patti D'Arbanville

One of Cat Stevens' most enduringly popular songs has been his 1971 single "Wild World," and, as is the case with many of his songs, there's a story behind it. That story involved a breakup with his girlfriend, Patti D'Arbanville. While D'Arbanville went on to become a popular star in such TV series as "Wiseguy" and "Third Watch," at the time the American-born actor was best known as a model, before appearing in several of pop artist Andy Warhol's experimental movies.

"We'd had some great times together, but I started recording and she was doing her modeling and it just became like two different worlds," Stevens recalled in an interview with Billboard. At the time, he'd recovered from tuberculosis and was poised to re-enter the music world with a whole new persona. "And because I'd had such an experience of almost falling off the planet, I knew there were a lot of dangers out there so it was kind of me talking to myself about the second career I was about to embark on and also talking to her about her career," he explained. "We'd basically split at that point, and that was the ode to our parting."

The near-death experience that led to his spiritual reawakening

A huge turning point came for Cat Stevens in 1976, when he decided to take a swim in Malibu. As he recalled during an appearance on BBC Radio's "Desert Island Discs" (via the Independent) he'd picked the wrong time of day, with a strong current pulling him farther out to sea while he fought a losing battle to swim to shore. "There was only one thing to do and that was to pray to the almighty to save me. And I did," he said. "I called out to God and he saved me. A little wave came from behind. It wasn't big. It was just simply pushing me forward. The tide somehow had changed and I was able to get back to land."

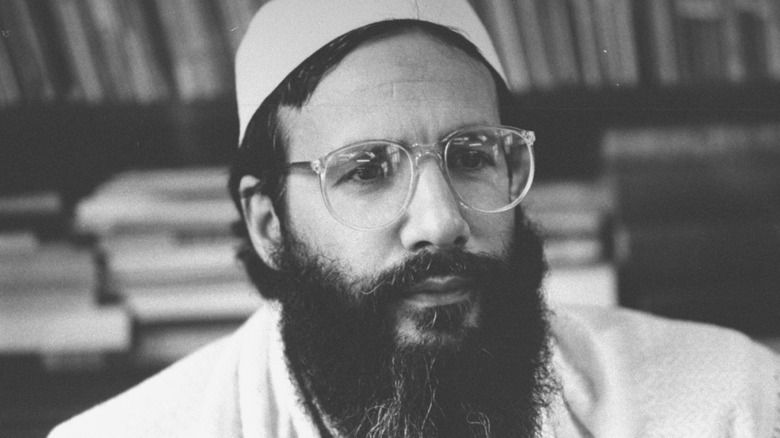

Not long after that, Stevens' brother gave him a copy of the Quran, introducing him to Islam and the path he would eventually take. "I would never have picked up a Quran," he said. "But it became the gateway. After a year I could not hold myself back. I had to bow down."

After the near-death experience that changed Stevens forever, he became a Muslim and gave up music completely, setting aside his guitar and changing his name to Yusuf Islam. As he told Guitar World, "People asked me how could I leave and just give up music, but it was because I'd actually found what I was looking for."

Cat Stevens founded some Muslim schools in London

When Cat Stevens converted to Islam and became Yusuf Islam, he stopped touring and recording. Instead, he focused his energy — and a significant amount of his money — on establishing some Muslim schools in London. That mission began after he and his wife welcomed their first child, daughter Hasanah. "I suddenly thought 'Hang on, what school am I going to send her to?' ... I had a job to teach my child not only to be academically successful, but how to live," He said in a 2015 interview with the Mosaic Network (via The Conversation).

He, his wife, and a group of like-minded friends decided to set up a school, which eventually became several. "We actually run three schools: a primary school, mixed boys and girls; a secondary girls' school; and a secondary boys' school," Stevens wrote on his website. Two of those schools are run by the Islamic Circle Organization: Brondesbury College (for boys) and Islamia Girls School, both operating under the auspices of Yusuf Islam Foundation Schools.

He has disputed reports that he entered into an arranged marriage

Following his conversion to Islam, Cat Stevens married Fawzia Ali. At the time, there were reports that this was no run-of-the-mill romance, but had actually been an arranged marriage. Speaking with The Guardian in 2006, however, Stevens insisted that was a mischaracterization. "I simply had two girls that I was, in a way, interested in marrying," he explained. "I invited them home separately and asked my mother which one she thought I should marry and, by God, she was perfectly right."

Apparently she was, given that Stevens and his wife have remained spouses ever since — and are the parents of five children, four daughters and one son (another son died weeks after birth). In 1999, Stevens admitted that he and his wife were already exploring options when it came to arranging marriages for their daughters. "We're consulting now," he told the London Times (via Majicat), explaining his philosophy of marriage. "I knew marriage was not just a selfish thing between two people but about a bonding between families," he said, adding, "We believe that love really blossoms after marriage but there has to be attraction."

Ultimately, though, Stevens has come to believe that true love extends far beyond this mortal realm. "Love has many levels, and love of God is very profound," he told Interview magazine. "It's certainly more lasting."

Cat Stevens lost fans when he supported the fatwa against Salman Rushdie

Cat Stevens' embrace of the Muslim faith and transformation into Yusuf Islam took a dark turn after the publication of Salman Rushdie's controversial novel "The Satanic Verses." Rushdie was decried for blasphemy by Muslims worldwide due to the book's depiction of the prophet Mohammed, with the book sparking violent protests and attacks on bookstores that carried it.

That ire turned deadly when Ayatollah Khomeini, supreme leader of Iran, issued a fatwa against the writer, resulting in a $3-million bounty on Rushdie's head. That was when Stevens jumped in, reportedly declaring his full support of the Ayatollah's call for Rushdie to be put to death. When appearing on a British TV show, Stevens discussed a protest in which Rushdie was burned in effigy. ”I would have hoped that it'd be the real thing," he declared (via The New York Times). Stevens went on to state that if Rushdie showed up at his home seeking asylum, he'd rat him out. ”I might ring somebody who might do more damage to him than he would like,” the singer coldly said. ”I'd try to phone the Ayatollah Khomeini and tell him exactly where this man is."

Fans of the singer's gentle, lovely music were obviously horrified, and radio stations stopped playing his songs. Years later, Stevens insisted he'd been set up by journalists, and wasn't actually calling for Rushdie's death. "I was cleverly framed by certain questions," he told The Guardian in 2020. "I never supported the fatwa."

He negotiated the release of British hostages during the Gulf War

After the Gulf War erupted in 1990, Cat Stevens wound up being a key player in securing the release of some British citizens being held hostage in Iraq. The devout Muslim negotiated with the Iraqi government, his goal being to arrange for the release of 40 British hostages, including some who were sick or elderly. Stevens appealed directly to Iraq's president, Saddam Hussein, begging for their release. Ultimately, Stevens wasn't able to free all of them, but did manage to convince Hussein to free four, all of whom were Muslim.

Three decades later, one of the hostages impacted by Stevens' efforts wrote about the experience in an essay published in Prospect. Sameer Rahim was just 9 years old when he and his family were taken hostage during a 1990 vacation in Baghdad. He and his mother were freed that August, along with all the other women and children, but his father remained in captivity until becoming one of the hostages to be released due to Stevens' efforts.

Cat Stevens was placed on the no-fly list and denied entry into the U.S.

In 2004, Cat Stevens (then going by Yusuf Islam) boarded a commercial jet airliner in London, heading to Washington, D.C. The flight was diverted to Maine, where Stevens was taken off the plane and apprehended by federal agents. "The door opened and in walked six gigantically tall, you know, uniformed officers, and they kind of came to me directly, and said, 'Are you Yusuf Islam?' And I thought, what is going on?" the singer told ABC News. "Then I got interviewed by some FBI agents, and that was like the beginning of what I began to realize was a terrible ordeal which I was about to go through."

It was at that point he discovered that he'd been placed on the U.S. government's no-fly list, for a shocking reason. "Yusuf Islam has been placed on the watch lists because of activities that could potentially be related to terrorism," said Brian Doyle, spokesman for the Department of Homeland Security. "It's a serious matter."

Another government official, who wished to remain anonymous, told CBS News that authorities had reason to believe that Stevens had been donating to terrorist organizations, including Hamas. "The one positive thing I can say is that a lot security officers are pleased because they got my autograph," said Stevens, who was sent back to London and barred from entering the U.S.

He has denied claims that he financially supported terrorists

Being placed on Homeland Security's no-fly list because he was allegedly funding terrorism blindsided Cat Stevens. He insisted those accusations were unfounded. "It's not true," his brother, David Gordon, told CBS News. "His only work, his only mindset, is humanitarian causes. He just wants to be an ambassador for peace."

However, there were some suspicious incidents in the past. In July 2000, he was deported from Israel shortly after arriving in Jerusalem. At the time, the government claimed that when he'd previously visited in 1988, he secretly delivered thousands of dollars to Hamas. "There was a problem with allowing him into the country because he is a Hamas supporter," Israel government official Moshe Fogel told Reuters (via ABC News).

Stevens, however, has continually denied offering any support to terrorist groups. "Like all right-minded people, I absolutely condemn all acts of terrorism," he said in a statement on his website. According to Stevens, his 1988 visit to Israel had been mischaracterized by the government; he'd actually been there to provide humanitarian aid to Palestinians who'd been injured by Israeli soldiers. "I have never knowingly supported Hamas or directed money to them," he wrote. "But according to the viewpoint of the Israeli authorities, whenever a person feels sorry for the poor victims of occupation including orphans, the disabled, widows and medical cases, if you try to help give charity to them — be warned, you may be considered a terrorist!"

Cat Stevens refused to allow one of his songs to appear in the film Moulin Rouge

Years before Baz Luhrmann's acclaimed film "Elvis," the Australian movie director won over critics and cinema fans alike with his lavish musical "Moulin Rouge!" While making the film, Luhrmann planned to open the film with Cat Stevens' "Father and Son." "It was the most amazing song that we all felt was perfect for this opening of the film," the movie's executive music producer and music supervisor, Anton Monsted, told Entertainment Weekly.

As Luhrmann explained in an interview with CinemaBlend, there was even a preliminary test filmed in which Ewan McGregor sings the song. However, when Stevens was approached about granting permission to use the song in the film, he refused. "And at the time, Cat Stevens, and I absolutely respect him, and I want to be crystal that I was not in any way disrespectful of Cat Stevens' decision, that Cat Stevens said, 'Look, I read the script and, as a Muslim, they're not married, and they're together, and I can't allow that,'" Luhrmann said, recalling Stevens' rationale for not allowing his song in the movie.

However, Luhrmann recalled subsequently reading an interview in which Stevens admitted he regretted not allowing "Father and Son" to be included in the film. "And I know because I reached out to Cat later on, and he said can we use that footage on a Blu-ray or something," Luhrmann told CinemaBlend. "So I know he gave permission."

Other artists have had hits with his songs

At the beginning of his career, Cat Stevens' songs were recorded by other artists, and that trend continued throughout the years. In fact, various acts have charted major hits with their versions of his songs. Among these is Rod Stewart's cover of "The First Cut is the Deepest," which spent five weeks in the charts in 1977, peaking at No. 43. More than two decades later, Sheryl Crow scored an even bigger hit with her 2003 cover of that same song, which spent a whopping 36 weeks on Billboard's Hot 100, climbing to No. 14.

In addition, Stevens' "Peace Train" has been recorded by Dolly Parton, Don Williams, Richie Havens, the Ventures, and 10,000 Maniacs. Jimmy Cliff and Maxi Priest covered "Wild World," while other artists who've recorded his music run the full gamut of music. Ranging from grunge pioneers Pearl Jam to Vegas fixture Wayne Newton, those artists include the likes of Johnny Cash, New Order, Sarah McLachlan, Patti Labelle, Elton John, The Mavericks, Gilberto Gill, Yo La Tengo, and others.

While Stevens attempted to distance himself from his music after converting to Islam — even asking his record company to stop selling his records — over time he'd come to embrace his old songs. "Today, my songs of the past represent a very important and dynamic period of my life and stand as a record of my innermost spiritual hopes and inspired dreams," he wrote on his website.

Cat Stevens was romantically involved with Carly Simon and inspired one of her biggest hits

Carly Simon has been a huge star for decades whose big break came in 1969, when she was selected to open for Cat Stevens at famed LA venue the Troubador. She was then asked to open for him at Carnegie Hall in New York City, and she invited him over for dinner, which would be their first date.

Simon was nervous, and Stevens was late. "And I sat down on the bed with my guitar," she told Steve Baltin for his book, "Anthems We Love," revealing she began singing about how much she was anticipating his arrival. "So I just started the song and I wrote the whole song, words and music, before he got there that night," she recalled. That song, of course, was her 1971 hit "Anticipation," which spent 13 weeks on Billboard's Hot 100, and found a whole new audience several years later when it was used in a TV commercial for Heinz ketchup.

They dated briefly, but the relationship didn't last. Then, one day in 2010, Simon received a message. "I'd just gotten back from a day of publicity. I had mascara all over my face. And they said Yusuf Islam is here to see you," she told Showbiz 411. "I hadn't seen him since 1976 ... I cannot tell you how good it was to see him. He hasn't changed. He's just remarkable."

His song Sad Lisa was inspired by a real person

Among the many beloved tracks on Cat Stevens' album "Tea for the Tillerman" is "Sad Lisa." That song was inspired by an actual Lisa, a figure from Stevens' past.

"She was a Swedish au pair for our family when we lived above the café," Stevens told Record Collector, referring to the London café his parents operated, and where he worked as a teenager. "I wrote that first time on the piano in our living room bought as a present for my sister's birthday. I was learning guitar and tried to transcribe the chords I knew for piano, though I never had a tutor or any lessons," he said. "I thought it had a beautiful, almost classical melody and a French lilt like those melancholy ballads they excel at."

Recalling what the real-life Lisa was sad about, Stevens admitted he never really knew for sure, but did offer a theory. "Maybe she was dreaming about a boyfriend," he said.

Cat Stevens does not consider himself a very good guitar player

Cat Stevens has typically accompanied himself on guitar when performing, and anyone who's seen him live or even listened to his recordings would certainly feel that he'd developed a certain degree of prowess on the instrument. Stevens himself, however, doesn't share that view.

"I never really learnt the intricacies of fingerpicking properly," Stevens admitted in an interview with Guitar World, explaining that, as a self-taught guitarist, he lacks the technical skills that many trained guitar players possess. "I mean, even today, I'm shy of playing in front of someone like Paul Simon because I never learned anything properly," he said. "But the way I did it was kind of unique and that's why I suppose it works in my songs."

While learning to play guitar, Stevens' inspirations ran the gamut, ranging from Scottish folk singer Bert Jansch to The Beatles. "The problem was I never had an electric guitar, so it was always acoustic," he explained. "So I tended to write on an acoustic and I was always more of a rhythm guitarist than a solo player. I couldn't do that."

He remade his most famous album 50 years later

While Cat Stevens did display some antipathy to his musical past after his conversion to Islam, he eventually got over it. That was abundantly clear when, in 2020, he recorded a whole new version of his seminal 1970 album "Tea for the Tillerman," 50 years after the release of the original.

The song "Father and Son," he explained in an interview with NPR's "All Songs Considered," offered him a rare opportunity to duet with himself. "There's the son and there's the father," he said. "And right now, you're going to hear me singing the whole song except for the son's part because the son is going to be me, which we've lifted off a recording from the Troubadour and back in 1970. So, you got me like 50 years ago singing with me today. Wow."

For the rerecorded album, Stevens revealed a new iteration of the original album cover, similar yet different. The titular Tillerman, for example, is costumed as an astronaut, while the children playing in the tree have likewise been updated, with one wearing headphones and the other playing a game on a smartphone. "We've got this white, pristine moon and the kids are now playing, but they're not playing together anymore," he explained, revealing the new album art reflected the worsening of the environment due to climate change. "So it's a kind of a darker version of the original cover," he added.