Mysteries About Ancient Egypt That Have Been Solved

Is there a civilization more mystical, magical, and mysterious than ancient Egypt? There are the Pyramids of Giza, the Great Sphinx, vast deserts, godlike pharaohs strolling through ancient palaces, the richness of the Nile, and bizarre pantheon of animal-headed gods. Then there are golden tombs housing millennia-old mummies in sacrophagi, exotic regalia like the pharaoh's crook and flail, hieroglyphs encoded with secret meaning, nigh-mythical names like Tutankhamun, Ramses, Nefertiti, Cleopatra. Even Egyptologists who've studied Egyptian history for decades must get lost in the mystique now and then.

But despite centuries of intense archaeological scrutiny, numerous ancient Egyptian mysteries still remain. Did laborers build the pyramids using the tried-and-true explanation of ramps, pulleys, lubrication, and so forth? What exactly does the Sphinx mean, and was it actually recast from a lion's head into the head of a pharaoh? Was Cleopatra really buried in Alexandria, and then her tomb swallowed by a flood? What happened to Nefertiti's body? Such questions represent the final, unsolved mysteries of ancient Egypt.

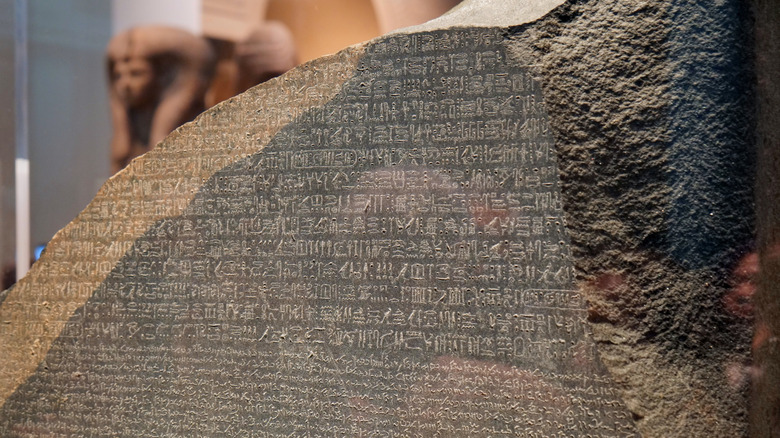

At this point, more questions have been answered than not thanks to discoveries that changed what we know. Bit by bit, researchers of all stripes and disciplines have diligently chipped away at the vast horde of Egyptian information and knowledge, starting with the most critical step: Decoding the Rosetta Stone in 1822, which allowed us to read Egyptian writing. Since then, we've shed light on many other mysteries, including the nature of the so-called "pharaoh's curse," the mystery of the Persian army that went lost in Egypt's sands, the reason why some mummies have red hair, and most recently, a big part of how the pyramid builders transported their materials. Though some explanations are still debated, many of the lingering questions about Egypt are pretty close to being answered.

Solved: How do we read Egyptian scripts?

Nowadays, a three-second Google search will yield entire classes about how to read Egyptian hieroglyphs. What many people don't realize is that they aren't just pictures — each picture represents a consonant. A double reed leaf? That's just a fancy letter "y." So how do you read hieroglyphs? Left to right, or right to left in little clusters, but without vowels — Egyptians didn't write down their vowels.

But they also didn't only write using hieroglyphs. There's Demotic, which is an Arabic-looking kind of everyday script, and a less ornate form, hieratic. On top of all this, some Egyptians under the Ptolemaic dynasty (about 323 to 30 B.C.E.) wrote using Greek letters because the ruling elite was Macedonian Greek. Their language was Coptic, and it's because of Coptic that French layman Jean-François Champollion unraveled all the rest of Egypt's scripts in 1822.

Champollion's discovery not only changed history, it overhauled it. Imagine being confronted with the thousands upon thousands of papyri and inscriptions of ancient Egypt in hieratic, Demotic, hieroglyphic, and Coptic and being unable to read it. It took the Rosetta Stone — a stone stela (tall slab) — that contained a decree issued under King Ptolemy V of the Ptolemaic dynasty to unlock it all. In a moment of fantastic luck for the future, the Rosetta Stone was written in demotic, hieroglyphic, and Coptic so that speakers of different languages could read it. Coptic proved the bridge between scripts, and the mysteries of ancient Egypt started to melt away.

Solved: Why do some mummies have red hair?

When Gebelein Man was discovered in 1896 in a dry, shallow grave of desert sand, he presented quite a little puzzle to researchers. As one of the oldest mummies we've found from ancient Egypt, he dated to about 3400 B.C.E., i.e., pre-dynastic Egypt — before the first pharaoh, Menes, unified the country. Named after the region where he was discovered, Gebelein Man seemingly underwent a simpler version of Egypt's later, more elaborate mummification process. But the dry sands of Egypt and time performed the brunt of his preservation. Also, he was probably murdered, as his shoulder blade and ribs showed damage consistent with a 5-inch dagger.

Gebelein Man was also nicknamed "Ginger" because of a feature that seemed strange for the region: He had red hair. Even as recently as 2016, there were attempts to transpose notions of modern multiculturalism onto ancient Egypt and claim that Ginger was a ginger because some Egyptians were naturally blonde, blue-eyed, fair-skinned, and such. In reality, Egyptian dead were treated with henna as part of the chemical mummification process. Yes, that's the same plant-based dye people use for temporary tattoos nowadays. It even seems like Pharaoh Ramses II regularly dyed his hair with henna to prevent the white from showing, and some Egyptian mummies also have red fingernails because of the same chemical treatment. With this in mind, Gebelein Man's hair seems to indicate that Egyptians included henna in the mummification process as early as 3400 B.C.E.

Solved: How did the pyramid builders get their materials?

Now we have to disappoint all of the "It was aliens" meme lovers of the History Channel's notoriously unhistorical "Ancient Aliens" show. As that show postulates, there's no way that pre-modern humans could have done all this fantastic Pyramids of Giza stuff. It must have been aliens. And while awe is the correct feeling when beholding the pyramids, it ought to be awe at the talent, willpower, and know-how of past people. With that said, there's an avenue for potentially fantastical explanations to creep into the discussion, because we're still not 100% sure how ancient Egyptian laborers built the pyramids.

In 2024, however, we came one step closer. Back then, researchers made a monumental find that explains how the pyramid builders hauled all of the stone blocks to their build site. The Nile provides the most reasonable way to transport these materials, but the river is four miles away to the east. This distance might be okay for a few blocks, but according to National Geographic, the Great Pyramid alone was constructed using 2.3 million blocks, with each one weighing between 2.5 to 15 tons.

Lo and behold, new research discovered a lost branch of the Nile that runs exactly along the route on which all 31 Egyptian pyramids sit. As Euronews reported, that lost "Ahramat" Branch is 39 miles long and got buried by the Egyptian desert long ago. It looks like the Ahramat Branch supplied the pyramids' builders with what they needed, from the Lisht Pyramids in Upper Egypt all the way to the Giza Pyramids in Lower Egypt.

Solved: What caused the pharaoh's curse?

We've all heard of the pharaoh's curse, right? Or the mummy's curse, or King Tut's curse. As Penn Museum quotes an inscription reportedly found on an Egyptian tomb, "Cursed be those that disturb the rest of Pharaoh. They that shall break the seal of this tomb shall meet death by a disease which no doctor can diagnose." Whether this inscription exists or not, it's true that explorers who've plumbed the depths of Egyptian royal tombs have often come down with sudden, lethal illnesses. Lord Carnarvon, the financier of the Tut excavation, died from blood poisoning within months of visiting Pharaoh Tutankhamun's tomb. Within 10 years, six of the 26 people on the expedition had died.

But here's the thing: The air inside Egyptian tombs was sealed for millennia, and the bodies inside decayed as mold and bacteria flourished. As National Geographic reports, mummies tend to carry two types of hazardous mold: Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus flavus. These molds compromise immune systems and can be dangerous for those not in excellent health. The lungs are especially vulnerable, and tomb walls are also covered with bacteria that's bad for the pair of organs. The air is also filled with traces of ammonia, formaldehyde, and hydrogen sulfide, all of which can cause pneumonia, if not death. And sometimes, bats take up residence in tombs and carry a fungus with them that also assaults the lungs. What's the lesson here? The curse of the pharaohs is more the curse of unventilated air.

Solved: What happened to King Cambyses' missing army?

Is it possible that an entire army of 50,000 people could go missing in the desert and never be found? This is the mystery of the army of the Persian king Cambyses II. As historical texts tell us, he was leading his troops across the western Egyptian deserts to enslave the Egyptian city of Ammon in 524 B.C.E. In "The Histories," published between 426 to 415 B.C.E., the Greek historian Herodotus writes (via Tufts), "But before his [Cambyses'] army had accomplished the fifth part of their journey they had come to an end of all there was in the way of provision, and after the food was gone, they ate the beasts of burden until there was none of these left either." Eventually, the army turned to cannibalism, and they all died in the desert.

But Herodotus was only repeating a story he'd heard. And despite such a vivid account, the truth of the tale has remained a mystery for over 2,500 years. Folks have searched the desert since at least the 19th century looking for the remains of the army. There was one find in 2009 — hundreds of bones and some Persian equipment around the right spot — but there haven't been any follow-ups into this lead.

In 2014, Leiden University made a breakthrough. As Science Daily reports, evidence points to a cover-up by Cambyses' successor, King Darius I. In this scenario, the future pharaoh, Petubastis III, ambushed Cambyses en route and obliterated his army. The "lost in the desert" cannibalism tale was a piece of political propaganda that Darius used to lambast Cambyses for incompetence and also cover himself.

Solved: How did King Tut die?

Even though Egypt lived under its pharaohs for over 3000 years, most of us only know a handful of them by name. Take Tutankhamun, the "boy king" who lived a mere 18 or 19 years and died in 1,323 B.C.E. Many people know King Tut — as he's commonly called — because of his treasure-filled tomb (with one bizarre item that baffled scientists) or his golden death mask (pictured above). His short reign consisted largely of correcting the course of his predecessor and father, Akhenaten, who outright replaced Egypt's millennia-old religion with a new religion dedicated to the sun god, Aten. King Tut also suffered from a host of physical problems related to his inbred bloodline.

But it's King Tut's sudden death that's proven a mystery. In 2010, researchers discovered evidence of malaria in his mummy, which, when combined with a degenerative bone disease, might have killed him. But recently in 2023, Egyptologist Sofia Aziz posited a different cause of death. As BBC Science Focus explains, she points to a fracture in Tut's leg caused by something like a high-speed chariot crash. This suggestion flies in the face of the 2010 conclusion because previous research concluded that Tut couldn't even stand in a chariot because of his club foot (from being inbred). She further suggests that Tut was essentially drunk driving. Because Tut's immune system was inherently weak, the open wound and fracture would have caused an infection that killed him. This scenario is far from being universally accepted, but it does help bring another one of ancient Egypt's enduring mysteries to a close.

Solved: What's the purpose of the pyramid shafts?

While we could end on any number of Egyptian mysteries that were solved, we're going to finish with one that confused archaeologists for decades: The shafts in the Great Pyramid at Giza. Looking at the pyramid, there's a complex, ultra-precise series of tunnels leading up from tombs to the air outside. In the 1600s, researchers assumed they were ways for the living to either communicate with Pharaoh Khufu inside or lower food to him. By the 20th century, explanations turned to some of that much-needed ventilation we talked about. But past decades have brought a final reason to light — one connected to Egypt's predominant religious and cultural preoccupation: the afterlife, or Egyptian underworld.

To ancient Egyptians, life on Earth was a mere preamble to the afterlife. When a person died, the soul had to make a dangerous journey to arrive at its final resting place. Hence the "star shafts" hypothesis, as Discover Magazine explains, where the shafts in the Great Pyramids are pointed to various "imperishable" celestial bodies, particularly in the Orion Belt. The implication is that the shafts helped guide the dead pharaoh, Khufu.

Beyond this basic idea, specifics get complicated. In the 1960s, for instance, Alexander Badawy and Virginia Trimble suggested that the shaft leading out of the queen's chamber points at a star in Ursa Major, while another shaft points to Sirius, the brightest visible star in the sky. Not everyone is on board with the star shaft idea, but if it's not true, then the alignment of the Pyramids at Giza and their shafts is uncanny, indeed.