The Fart That Caused 10,000 Deaths

The Ancient History Encyclopedia shares the hilarious account of how the 3rd-century B.C. Greek philosopher Crates comforted his future brother-in-law, Metrocles of Marneia, after a mortifying fart. Metrocles, a student at Aristotle's Lyceum, had been tasked with giving a lecture and inadvertently turned it into a lesson in cheese-cutting. Historian William Desmond says, "Metrocles farted audibly and was so ashamed that he shut himself away from public view and thought of starving himself to death. But Crates visited him, fed him with lupin-beans, and advanced various arguments to convince him that his action [of farting] was not wrong or unnatural and had been for the best in fact. Then Crates capped his exhortation with a great fart of his own."

Thankfully, that story had a happy rear ending. But as you can tell from Metrocles' dramatic reaction to his own flatulence, farts weren't always a laughing matter in antiquity. Atlas Obscura observes that ancient Egyptians, Romans, and Greeks believed beans were "an emblem of death." By extension, that made farts a death knell. As Daily Beast contributor Candida Moss points out in her article, "How a Fart Killed 10,000 People," famed philosopher and mathematician Pythagoras abstained from eating beans because he worried a person might "fart out" their soul while breaking wind. In fact, per the American Journal of Psychology, the Greek word 'anemos' translates to "wind" while the Latin form 'anima' means "breath or soul." (Coincidentally, the Irish word 'anal' means "breath" and 'anam' translates to "life" or "soul"). Back in the days when people took toots seriously, farting could indeed mean you were about to breathe your last breath.

Not-so-silent butt deadly

In "How a Fart Killed 10,000 People," Candida Moss examines the gravity of flatulence throughout history. One time, that gravity dragged thousands of people down to the grave during Passover. Admittedly, it's difficult not to crack another fart joke, but for now, let's just hold it in and get to the bottom of what happened. As recounted in Who Cut the Cheese? A Cultural History of the Fart, according to historian Flavius Josephus, the deadly flatulence happened in 44 AD, not long after the death of King Herod. While "multitudes" of Jews partook in a Passover feast, a Roman soldier standing guard "pulled back his garment," assumed the tooting position, and "spoke such words as you might expect upon such a posture."

In a modern context, you might expect the soldier's cheeky speech to resemble that lighthearted scene in Ace Ventura where the pet detective pretends to talk through his backside. But the Roman's act reeked of malice. The gigantic gathering erupted into a riot as "the rasher part of the youth" among them began throwing stones at the Romans. Roman reinforcements arrived, prompting the congregation to flee. Amid the bedlam, people trampled and crushed each other. Josephus wrote that 10,000 people perished in the process.

Socrates was the butt of deadly fart jokes

A Roman soldier incited a riot during a religious feast by speaking with a fart, but centuries earlier, a Greek comedian may have helped helped kill a great philosopher by farting with words. In 419 B.C. the comic playwright Aristophanes published The Clouds, which mocked Socrates in flatulent fashion. In the play, the philosopher dishonors Zeus by claiming that it was not the god of thunder who made the sky rumble. Instead, Socrates says swollen clouds are cutting the cheese and compares it to the "prolonged rumbling" that occurs when someone eats too much stew and has to release gas. Elsewhere, Aristophanes' Socrates claims that gnats buzz through their trumpet-like butts.

The Clouds concludes with the sacrilegious gnat-fart philosopher lighting a torch and appearing to suffocate himself to death, after which he's chided for slighting the gods. One might interpret his demise as a morbid fart joke. In The Death of Socrates, Emily R. Wilson argues that "suffocation seems, within the play, an appropriate death for one who has relied on so many various forms of hot air. Socrates, who spouts windy nonsense, who worships the Air and Clouds themselves, and who explains thunder as a cosmic fart, finally gets the death he deserves."

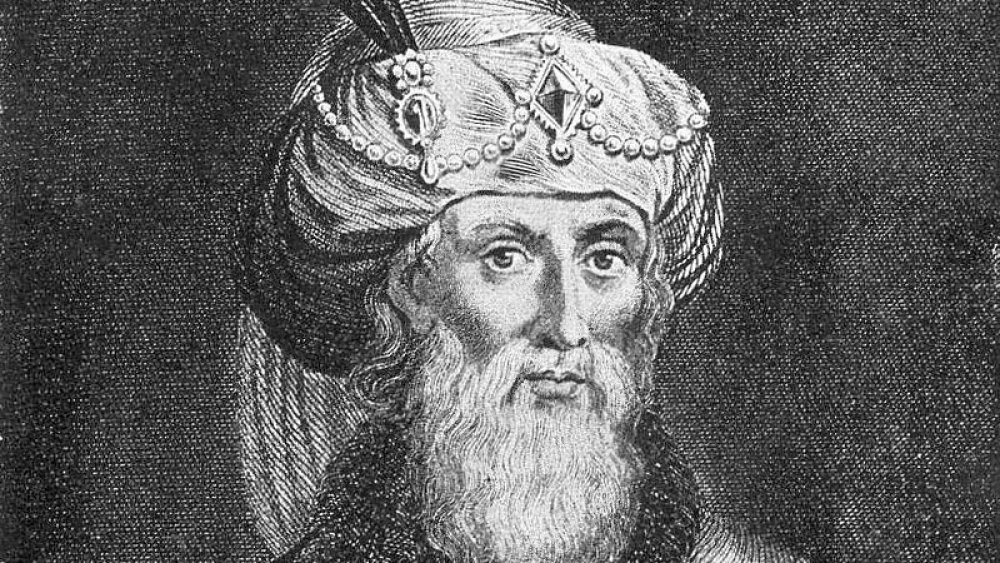

Per the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, in 399 B.C., Socrates was convicted and executed for religious irreverence. (Above the philosopher is presumably depicted telling people to pull his finger as a final request before he dies). According to Plato's Apology, the Athenians who called for the philosopher's death grew up believing The Clouds' depiction of Socrates. The real-life philosopher allegedly held Aristophanes more responsible for his fate than the actual accusers at his trial. He claimed the playwright "poisoned the jurors' minds while they were young," leading them to condemn Socrates to die by drinking poison.

The fart of war

In the past, a fart not only had the power to end lives; it could upend them and take down powerful people. For instance, Historic UK recounts how during the reign of England's Elizabeth I, the Earl of Oxford farted while bowing before the Queen. He was so utterly ashamed of himself that he left the county for seven years. Upon his return, Elizabeth quipped "My lord, I had forgot the fart!" Not every monarch has responded so kindly to butt burps. In fact, an ancient Egyptian king responded to a fart so harshly that it cost him his kingdom.

If history had a sillier sense of humor, the pharaoh would have been named "Toot-ankhamun" — or better yet, "Tootin'-comin'" — but instead, it was the less toot-ulent King Apries. As Mental Floss details, in 570 B.C., Apries sent sent his general, Amasis, to quell a rebellion, but Amasis found himself siding with the dissidents, who suggested he try to overthrow Apries. The pharaoh sent a messenger, Patarbemis, to retrieve the general.

At this point, all smell broke loose. Rather than obey the Apries, Amasis, who was mounted on a horse, raised his derriere and unleashed a fart for the messenger to take to Apries along with the warning that Amasis would return to fight. Apries didn't kill the messenger, but he mutilated Patarbemis, whose nose and ears were chopped off. This was a grievous misstep because the public loved Patarbemis. Now they hated Apries, who was soundly routed when Amasis arrived to take the throne.