The Most Painful Ways To Die Throughout History

The following article contains graphic descriptions of death.

Physical pain is a necessary evil. Our bodies have to know when they're taking damage so we can get out of the situation and learn to avoid hazards in the future. The rare people born without the ability to sense pain often suffer repeated, severe injuries throughout their life. They lack the feedback they need to tell them what's dangerous, what's a hazard, and what, put simply, will hurt.

But pain is also a weapon. Animals and plants can inflict it to deter predators or competitors, and human beings intentionally inflict pain on one another to exert control and exact punishment. Some even do it because they take a malicious glee in doing so. And because pain is a universal experience, it is also, to some degree, a universal fear. Nearly everyone fears pain. And severe pain, suffered at the end of life as the last sensation, is particularly horrifying.

Sticky fire

Fire is likely the first thing most people have been warned about throughout human existence. Anyone who doesn't believe it's dangerous only has to confirm for themselves once. Strategists have long sought to add to the destructive power of fire by making it sticky, ensuring that anything (or anyone) unlucky enough to be within an incendiary weapon's radius is more thoroughly destroyed.

The Byzantine Empire lasted as long as it did and broke many sieges of Constantinople in part because of Greek fire. The recipe for this weapon has been lost to time, but according to reports, this inflammable goo could be sprayed from specialized nozzles on ships and resisted water. The Byzantines sprayed its secret weapon over Arabs, Russians, and anyone else optimistic or naive enough to go against their navy. Later, the United States war effort in Vietnam became notorious for its heavy reliance on the conceptually similar napalm — a slow-burning, readily-propelled form of thickened gasoline.

Burns, as anyone who's carelessly grabbed a hot pan knows, can be enormously painful. Chillingly, the worst ones may not cause pain after a certain point, as they run deep enough to destroy the nerves. With skin and underlying tissue damaged by a burn, the sufferer will be at risk of dehydration (as one of the skin's functions is to retain the body's water), hypothermia (skin helps regulate temperature), and infection (skin presents a barrier to pathogens). Those who survive severe burns may face not only disfigurement but also enduring pain from damaged nerves and scars that heal too tightly.

Radiation poisoning

Certain types of radiation, called ionizing radiation, are dangerous because they can impact individual atoms with enough force to strip them of electrons. This changes their properties and, by extension, the properties of any molecules they make up — including DNA. If this affects enough of the cells in a human body, it leads to acute radiation syndrome, commonly called radiation poisoning (one of the many things that can happen when you're exposed to radiation). Radiation poisoning affected many of the people who lived near the Chernobyl disaster, as well as many initial survivors of the atomic bombing of Japan. A particular cruelty of this death is that the affected may appear to recover before again worsening and dying.

Radiation can damage any body systems, but the most evident damage will affect the skin, the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, the bone marrow, and in the most severe cases, the brain. Regarding the skin, redness, swelling, and blistering can occur, along with loss of the skin and associated tissue. GI symptoms appear as severe nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. These may temporarily resolve, only to reappear in several days as damaged cells die. Effects on bone marrow include general feelings of illness, with clinicians noting a drop in populations of all blood cells (as most are made in the marrow). Brain involvement shows up as anxiety and confusion, possibly interrupted by an apparent return to normality before the arrival of convulsions, coma, and death.

Patients with gastrointestinal and nervous system symptoms are likely to die within days or weeks, but even those who survive in the short-term are not home free. Death from acute radiation syndrome can occur up to two years after exposure, and high doses of radiation can also lead to an increased risk of many cancers.

Breaking on the wheel

A particularly gruesome torture inflicted on people unlucky enough to fall afoul of the law in medieval or early modern Europe was the breaking wheel. The breaking wheel could be used in different ways, depending on the time, place, and preferences of the judges and executioners involved. But all involved the systematic destruction of the major bones of the limbs, generally in public.

The heavy wheel could be dropped on the limbs in turn, or the condemned could be tied to it so the torturer could strike the body with another implement. Once the bones had been crushed, the unfortunate might have been jabbed and tormented with other instruments (think pincers or hot pokers). The very unlucky had their now-pliable bones threaded through the spokes of the wheel. The person braided to the wheel could then be set up to suffer for some days, though in other instances a more efficient execution coup de grace was carried out.

If this treatment seems extreme (which it should), there is one "happy" legend of a miraculous salvation from the breaking wheel. As the tales goes, when St. Catherine of Alexandria touched the wheel brought to torture and kill her, it exploded, and the shrapnel killed several would-be spectators. (Stay out of the splash zone, guys.) Catherine was then beheaded — a pretty easy out when you consider the most gruesome deaths of saints.

Hanging, drawing, and quartering

Today, inflicting suffering is not (officially) among the goals of the death penalty, but this was not always the attitude. For millennia, the suffering was often the point. And special horrors were reserved for those convicted of treason, which states had a special interest in discouraging.

From at least 1238, traitors in England — which could include Scots and Welshmen who did not consider themselves English and defied English attempts at conquest — could be hanged, drawn, and quartered. Convicts would be hanged and left to dangle and gasp but cut down before death. They would then have each limb tied to a separate horse, and these horses would then be driven away from the victim in separate directions, resulting in their arms and legs being torn from the body. These fragments might then be sent around the kingdom for public display as a warning.

Add-ons were available for the particularly unlucky, sometimes justified with the argument that they had committed multiple crimes and so deserved multiple punishments. They could be dragged behind a horse to the place of execution, dismembered (sometimes with the removed guts being thrown into a fire in front of them), and/or have their genitals severed. Conversely, they might be beheaded before the quartering, leaving their corpse to be desecrated after death.

Penalty of the sack

The ancient Romans loved punishment. Though most famous for crucifixion, Romans had plenty of other ways to rid themselves of the troublesome and unruly. You could be thrown from a tall rock, buried alive, or, if you had committed the especially heinous sin of killing your own parent, face the "penalty of the sack."

The penalty of the sack ("poena cullei" in Latin) saw the condemned sewn up into a bag. Unfortunately for all concerned, the victim wasn't in there alone — they were accompanied by a dog, a chicken, a snake, and a primate. From there, the prisoner and his reluctant animal companions would be thrown into a body of water if one was convenient. If not, they could be thrown anywhere the commotion might attract the attention of more wild animals. The pain and chaos of such a situation is difficult to imagine, but it seems inevitable (and was indeed the hope of the punishers) that the frightened, distressed animals would turn on the person and attack them.

As is common with incidents in classical history, historians and classicists debate whether the Romans ever carried such an execution out or simply talked it up as a deterrent. Even if the Romans can be let off the hook, Europeans who admired the concept cannot be. Indeed, the punishment of the sack is recorded as having been imposed In Germany as late as the 18th century.

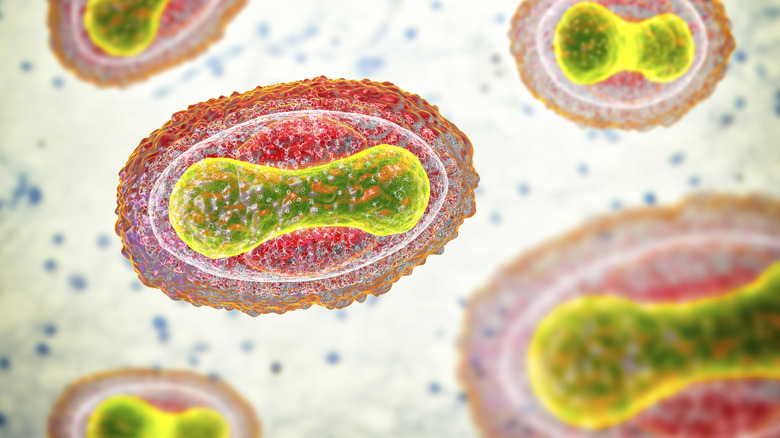

Smallpox

For centuries, smallpox was one of the most feared diseases that affected human beings. From the time of the pharaohs to the Carter administration, the affliction walloped the human population, causing high fever, pain, and the telltale lesions that could leave survivors badly scarred. In the most severe cases, they formed connected patches of inflammation over much of the body. Scientists have identified several forms of smallpox, and the most common form has a 30% case fatality rate. The most deadly forms, which cause uncontrolled hemorrhage or soft, flat lesions, leave very few survivors.

Human beings have weaponized smallpox throughout history. Tartars flung infected corpses over the walls of besieged cities, and British forces notoriously gifted virus-laden blankets to Native Americans. Additionally, unintentional introductions of smallpox have devastated previously unexposed populations across the Americas and in Australia.

In 1980, an aggressive vaccination campaign led to smallpox being declared eradicated in the wild. The last such case occurred in Somalia in 1977. In 1978, as the WHO prepared to declare the virus vanquished, a small outbreak at a laboratory in the United Kingdom claimed the life of Janet Parker, the last recorded smallpox victim to date. Today, the only acknowledged samples of the virus exist in hyper-secure labs in the United States and Russia. Whether this is necessary for research or too dangerous remains debated.

Box jellyfish

Australia is well-known for its dangerous animals, especially the venomous ones. In addition to snakes, the continent also boasts some of the world's most lethal species in the form of a snail, octopus, and jellyfish. Scientists posit that this potency comes from Australia's relative isolation before the European arrival. If the original species on the continent had venom, then the most evolutionarily effective way for descendants to advance fitness was better venom.

Off of Australia's coast lurk tiny but very dangerous jellyfish. The box jellyfish is the most dangerous, but Irukandji jellyfish are more frightening. In addition to the initially mild pain, swelling, nausea and vomiting one might expect from a toxin, Irukandji stings also cause a racing heart, high blood pressure, agitation, and a feeling of impending doom. And sometimes, the heart simply stops (through a mechanism that is not yet fully understood).

These wee jellies (2 centimeters in diameter!) can drift through most nets that stop their larger peers, and stings tend to occur in "outbreaks." Imagine a beach full of Australians suddenly shaking with the certainty that something terrible is going to happen immediately. The link between the syndrome doctors had observed and the sting of this particular jellyfish was first confirmed by researcher Jack Barnes. In 1961, he captured a specimen and, in a deeply Australian move, had it sting him. And a nearby lifeguard who allegedly volunteered. And his own 9-year-old son. All developed Irukandji syndrome, confirming Barnes' hypothesis, and all survived after hospital treatment. What Barnes' wife thought about all this is, unfortunately, not recorded.

Manchineel tree poisoning

The manchineel tree grows on certain Caribbean islands and along the coasts of the Gulf of Mexico, Central America, and South America. (This range includes Florida, which seems particularly dangerous.) All parts of the tree are poisonous, from the allegedly sweet-tasting fruit, to the sap, to the leaves, to the smoke if a fresh branch is burned. The manchineel is so ferociously toxic that specimens near inhabited areas have warnings painted on them or nailed to them. They often include the advice not to stand under the tree in the rain, as falling drops can carry the blistering sap.

Local people used the manchineel as a source of arrow poison and, after proper treatment, to build, drying the wood to neutralize its toxicity. Early Europeans didn't know what hit them when they tried to make use of the little tree they found. They tried to eat the little "apples" and their mouths blistered, with some unlucky noshers even dying after a single bite. They chopped wood from the tree and went temporarily blind when they rubbed their eyes afterward. Even the fatal arrow that killed Spanish conquistador Ponce de Leon may have been doctored with manchineel poison for that special anticolonial touch. Despite these centuries of Western contact, however, tourists to the Caribbean occasionally try to eat the little fruits they find with, at best, deeply uncomfortable results.

Strychnine poisoning

The poison strychnine comes from the strychnine tree of southeast Asia, the Indies, and northern Australia. This compound interferes with the ability of nerves to signal muscles to relax, resulting in painful clenching throughout the body. There's little or no interruption between episodes of the clenching, and sufferers remain fully conscious and lucid throughout the ordeal. Characteristically, patients present with their limbs stretched out, backs arched, teeth clenched, and their faces stretched into broad, unnatural smiles. Within several hours, sufferers may die from complications of muscles in the airways or areas that control breathing.

Strychnine in small doses can act as a stimulant (especially of sexual vigor), and so it was formerly used in Western medicine and persists to this day in some Asian traditional systems. (It was also, less irrationally, used for pest control.) Since it was formerly so available, strychnine was a popular weapon in murder mysteries (and occasional real-life murders), but the substance is now far more tightly controlled. It was, however, given to Thomas Hicks, an American runner, during the marathon at the 1904 Olympics, along with brandy and egg whites. He won gold!

Prion diseases

Prion diseases are terrifying. A substance called "prion protein" exists normally in the brain, but if it is exposed to a malformed version of itself, a sort of biochemical evil twin, the correctly shaped protein will "learn" the incorrect shape. The incorrect protein will spread throughout the brain of the unhappy sufferer (be they human, sheep, cow, or other mammal), forming clumps and causing degeneration of the tissue. Prion diseases are transmissible through inheritance, infected meat, or in some cases medical procedures (especially corneal transplants). They appear to always be fatal.

Mad cow disease, formally Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, resulted from prions entering the British beef supply and spreading to consumers. A particularly famous prion disease is kuru, which affected a tribe in New Guinea. The Fore people consumed their dead as part of their funerary traditions, and when one of them died in the early stages of a prion disease, this practice infected more of the tribe (there are many side effects of cannibalism). Kuru caused tremor, dementia, incontinence, and uncontrolled laughter among its victims. After the Fore moved away from this tradition in the mid-20th century, transmission stopped, but the slow fuse of the disease meant cases showed up for decades.

An even more alarming prion disease, fatal insomnia, occurs either by inheritance or by a chance mutation. The part of the brain that controls sleep is destroyed, leading (as the name implies) to trouble sleeping, a complete inability to sleep, hallucinations, dementia, and death.

Rabies

Rabies is very, very nearly always fatal: A handful of people have survived, but they represent a tiny, lucky fraction of infections. So what happens to your body if you catch it? After a bite from a domestic or wild animal — a dog, in 99% of human cases — the rabies virus begins a slow movement into the central nervous system. After an incubation period usually lasting several weeks, a patient will present with excitation, hyperactivity, and hallucinations, along with the telltale aversion to water or drinking. This "hydrophobia" comes from the intense and painful muscle spasms that may occur when a patient tries to drink, which may be so severe as to interfere with breathing. Death eventually comes from heart or respiratory failure secondary to damage from inflammation of the brain and spinal cord.

Rabies has been with humans and the animals living with them for millennia. Ancient Sumerian law codes set financial penalties for allowing a rabid dog to transmit the disease, and attempts to treat it are recorded in premodern texts across Europe and Asia. Happily, an effective (human) rabies vaccine was developed in France in 1885, and our dog friends began regularly receiving their own shots in the 1920s.

Flaying

Flaying is the act of cutting and peeling the skin off a person, generally as a punishment for treason, murder, or theft. The extraordinary pain this act causes is nearly matched by how disturbing it is, making it, at least theoretically, an effective deterrent. The torture could be drawn out for hours or days, if that was to be part of the punishment. Death could come from blood loss or shock, obviously, but also infection or hypothermia, given that the skin exists in part to keep germs out and warmth in.

Flaying has a long and uncomfortably vivid presence in European art, in part because of the technical prowess needed to depict it, and in part because people love gore. St. Bartholomew, an apostle whose saint's life indicates he died by flaying at the orders of the king of Armenia, shows up carrying his unsettlingly empty skin. The legendary Greek mythological figure Marsyas, a satyr who foolishly defeated the god Apollo in a music contest and was flayed for his hubris, also appears without his skin or in the act of losing it. Finally the grim semi-legendary story of the Persian judge Sisamnes, punished for corruption by having his skin removed and turned into a chair for his successor and son, has proven irresistible for a number of artists with a zest for the macabre.