The Hidden Truth Of The Dodo Bird

Sure, you think you know about the dodo. It's a sad tale of yet another species of extinct animal — one that you've likely encountered more than once. The bird died out, quick enough that its very name is now a byword for a whole species kicking the bucket. But didn't it kind of deserve it? Wasn't the animal a bit of a mess, with its ugly, poorly adapted body and willingness to just wander up to deadly humans? Not so fast.

Yes, this flightless bird that once lived on the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean is very definitely extinct. And, okay, given the fact that there are no living dodos left in the world — and that there haven't been since the 1680s — it obviously didn't fare well after humans began landing on the island in the late 16th century. But it wasn't as much of an evolutionary dead end as you might think. Dig deeper, and you'll learn that the dodo was actually quite well-suited to its environment and didn't do much at all to deserve its less-than-intelligent stereotype.

Neither was its extinction a simple story. In fact, new technology and some bold moves might make the matter of this species' end a less-clear affair than it may have once seemed. As it turns out, there's quite a lot more to learn about the long-gone dodo bird.

It was smarter than you think

The common image of the dodo is a bird that's simply too stupid to live. How else could it have fallen so hard and so fast if it wasn't a bit slow? But while no one recorded a dodo bird solving equations or inventing an internal combustion engine while it evolved on Mauritius, perhaps we've been a bit too hard on the poor thing when it comes to rating its intelligence.

There's physical evidence to back this up in a study of dodo endocasts (the interior of its brain case) published by the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. The researchers looked at the brain size-to-body volume ratio, and they concluded that dodos were likely at least as intelligent as other avian species, including its somewhat close relative, the pigeon. Admittedly, looking at brain size isn't a perfect measure of an animal's intelligence, but there's no physical indication that the dodo was some sort of avian dunce. Direct observation would be much better, but given that the last time the animal was seen alive was back in the 17th century, that avenue is pretty well closed. And, frankly, few sailors, naturalists, and others who wrote about dodo encounters were recording the sort of data modern biologists would hope to see.

It wasn't quite so dumpy looking

Besides the rather slanderous notion that dodos were idiots that basically walked up to humans and asked to be slaughtered, there's another unfair aspect of the extinct bird's reputation: its look. Earlier depictions of the animal aren't exactly flattering, showing a heavyset, lumpen bird that must have just stomped about its environment. But more clear-eyed looks at dodo remains, including a morphological analysis published in 2016 in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, give the species a better look — literally. Sure, bones make it clear that this bird was far from delicate, but its robust skeleton served a purpose, including relatively large kneecaps that would have given it an advantage when moving about in the lush vegetation and rocky terrain of Mauritius. A 2024 taxonomic review in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society further bolstered this claim.

These and other studies have since come to a kind of consensus, namely that the dodo was much slimmer and more upright than many old illustrations would have you believe. It was pretty speedy, too. This last point makes sense when you come across accounts from sailors who complain that it was actually pretty hard to catch a dodo — a situation that's a far cry from the idea of a big, dumb bird lumbering up to humans and basically offering itself as an easy meal.

It was well-adapted to its environment before humans showed up

Was the dodo just a coddled species that couldn't deal with the arrival of humans? Not exactly. While the dodo did evolve in an environment without any major predators, that doesn't mean it was doing the bird equivalent of lying on a chaise lounge eating grapes all day. If there wasn't a Mauritian version of a tiger hunting it down or other birds competing for similar resources, there was the environment itself.

A 2011 study published in journal The Holocene revealed evidence that the dodo species survived a major drought that hit Mauritius about 4,000 years ago. How bad was this event? An estimated 500,000 animals died over the course of decades, leaving their bones in a massive 5-acre deposit around a dwindling freshwater lake. While this die-off didn't end any known species, it's a clear indication that the dodo wasn't some delicate group of birds primed for a die-off. Like the other animals of Mauritius, it was a survivor.

Studies of dodo endocasts have found that the bird had a larger than expected olfactory bulb portion of its brain, which suggests that it was especially good at navigating through smell and sniffing out food sources. Other researchers have pointed out that dodo bones have strong muscle and tendon attachments, suggesting that it was both fast and strong. In particular, the tendon that controlled its toe was hefty enough that researchers drew comparisons to modern running and climbing birds.

The reason it went extinct is actually pretty complicated

So, what really killed the dodo? The common narrative that humans arrived and laid waste to the species isn't entirely wrong. The dodo appears to have been doing just fine in its native environment until Dutch sailors first came across it in the late 16th century. Scientists and historians estimate that the animal died out by 1693, less than a century later. Considering the worst ways humans have impacted nature, it's no shock that as far as the dodo is concerned, we were a major factor in their disappearance.

The extinction of the dodo is more complicated than overhunting, however. As in so many other environments, humans caused major ecological upheaval on Mauritius, including the introduction of non-native species like goats, pigs, and rats. These animals not only ate up many resources previously enjoyed by the dodo, but they also destroyed their nests. Given that the dodo was flightless, those nests were all on the ground and within easy reach of opportunistic new species. Even worse, the dodo reportedly only laid one egg at a time, making species recovery all the more difficult when nesting areas were overrun by hungry rats, monkeys, cats, or other critters. If, somehow, the dodo had survived into the modern day, it would have also faced challenges brought on by human-induced climate change. It did pull through many decades of major drought thousands of years ago in the Holocene, but new challenges would have been yet another factor in species pressure.

It has another extinct relative

The dodo is far from the only avian species to have gone to the great nest in the sky. In fact, it isn't even the only extinct flightless bird in the region. About 372 miles east of Mauritius is the island of Rodrigues. Once upon a time, there was another big, flightless bird strutting about the island: the Rodrigues solitaire. This species, closely related to the dodo, appears to have been a bit tougher than its Mauritian cousin.

With territory at a premium, the Rodrigues solitaire evolved a club of bone on each wing, which males used when fighting for primacy. We have perhaps some better observations of this species thanks to a group of French protestants. While attempting to set up a colony far from Catholic France, they were marooned on Rodrigues from 1691 to 1693, right around the time the last living dodos were observed a few hundred miles west. One of the group, François Leguat, devoted a fair amount of space in his diary to describing the Rodrigues solitaire, from its looks to its behavior. Similar to the dodo, the Rodrigues solitaire only laid one egg at a time, though the chick benefited from the care of two parents until it could survive on its own. Ultimately, however, human encroachment spelled a doom similar to that faced by the dodo, including widespread damage courtesy of invasive species like rats and cats. By the mid-1700s, the Rodrigues solitaire was no more.

People definitely ate dodo meat

In this age of jet-powered travel and, for many, easy access to food, the travails of a cross-ocean voyage in the age of sail can be hard to imagine. Voyages could take months or even years, and sailors lived in cramped, usually dirty quarters. Food was often a particular problem, as it was hardly possible for sailors and ship's passengers to stop off at the nearest grocery store. If the supplies of hardtack, cheese, meat, and other victuals were running low (or going bad), then people could get hungry indeed. With that in mind, it's no wonder that people visiting the remote island of Mauritius readily ate dodo meat.

That may be surprising if you've been exposed to the myth that dodo meat was no good. But multiple historical accounts note that the animal tasted just fine, if not exactly gourmet. Sailors generally preferred other birds as game, including the dodo's pigeon cousins and even parrots, assuming the seafarers were fast or canny enough to catch the flying birds. Some even later wrote that dodos, which were occasionally referred to as wallowbirds, was actually pretty good (though perhaps months of eating ship rations gave those reviews a little extra boost).

There's only one mummified dodo in the world

Perhaps one of the most haunting things about the fate of the dodo is how little we have left of the species. Yes, there are written accounts and paintings of sometimes dubious accuracy, but what about physical remains? Those are alarmingly few and far between. Bits and bobs of dodo skeletons can be found in museums, but there's only one known specimen with scraps of soft tissue left on those bones. This rather lonely creature is all the more isolated given that it's exceedingly far from home in the University of Oxford's Museum of Natural History.

If you manage to see this specimen (or its high-res 3D scan), be sure to temper your expectations. This isn't a full-body mummy — it's a skull with some skin, a feather, bits of tissue, and some bones from the animal's eye and leg. Furthermore, what's on display in the museum is actually a cast of the skeleton, alongside a somewhat more lively model. The delicate, one-of-a-kind specimen is kept away from public view, made all the more valuable because it's currently one of the only sources that contain dodo DNA.

Researchers have also found rather poignant information on what killed this particular dodo. A close examination of its preserved head revealed tiny particles of lead shot, consistent with the kind of projectiles used in 17th-century weapons. While the dodo was struck in the back of the head, its impressively thick skull blocked the projectile. Still, it obviously didn't survive its last encounter with a human being.

Some dodos journeyed far beyond their home

While dodos are closely associated with the island of Mauritius, some were transported far beyond their isolated home. Their long voyages were the result not necessarily of human hunger but of intellectual curiosity and perhaps the hope that a dodo would be something to show off. English merchant and boat captain Emmanuel Altham attempted to get a live dodo to his family in Essex, England. In a letter to his brother-in-law, Altham listed off goodies he was sending back from a trip that included a 1628 stopover on Mauritius. Amongst beads and a jar of ginger was "a bird called a Dodo, if it live." In another letter, Altham again talked of an incoming dodo, "which for the rareness thereof I hope will be welcomed to you" (via "Mauritius Illustrated"). It's unclear if that dodo ever saw England's shores for itself.

In 1625, other dodos were sent to the court of Mughal emperor Jahangir as gifts for his menagerie. Others were reportedly prepped for travel to Europe, but only one seems to have made it to England for sure, with historian Sir Hamon L'Estrange reporting an encounter with a live dodo in 1638 London. Another perhaps made it to Amsterdam by 1626, according to an artist's caption. In 1647, at least one live bird was sent by a representative of the Dutch East India Company to the far-ranging business's station in Nagasaki, Japan (multiple dodos were reported at the company's headquarters on the Indonesian island of Java).

It's considered a national symbol of Mauritius

Though the dodo is long-gone, it still remains a considerable presence on the island of Mauritius. Now officially the Republic of Mauritius, the independent nation is home to a little over 1.2 million people, including many who proudly consider the animal to be a national symbol. It's likely to show up on your passport stamp, and there are plenty of dodo-branded souvenirs to be had on your next visit to the island.

For many of the island's people, the dodo is motivation to save other species that aren't quite dead yet. One such animal is the orange tail skink that was nearly killed off by invasive shrews arriving on a Mauritian island. Far from being the legend of a silly bird, the dodo has reminded some of the importance of conservation and mindfully managing the environment of Mauritius and its outlying islands.

The dodo has a complicated cultural legacy

If the dodo could somehow speak from its evolutionary grave — if it could speak at all — it would surely have a word or two to say about its reputation. Even Carolus Linnaeus, the 18th-century Swedish naturalist who became famous for classifying species and really should have known better, gave the poor dodo the Latin name of "Didus ineptus" ("inept dodo" in English)." Sure, it may be because the word "dodo" is possibly based on the Portuguese term for "fool," but Linnaeus and many other naturalists, explorers, artists, and writers could have given the dodo a break.

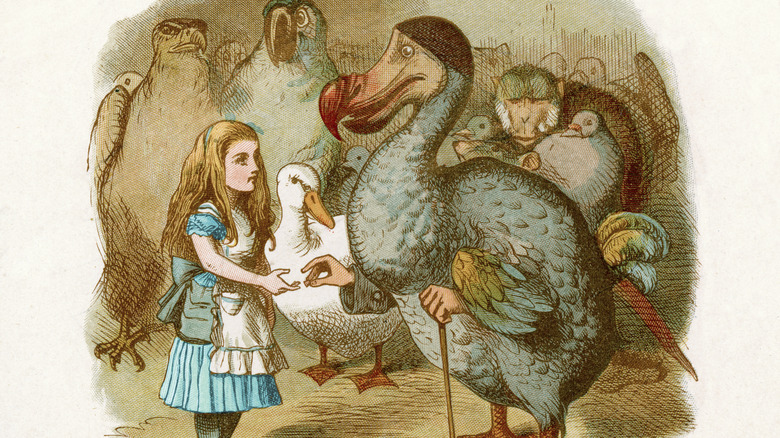

No dice, at least as far as Lewis Carroll was concerned. When incorporating a fantastical talking dodo into his "Alice in Wonderland" novel, Carroll (the pen name for Charles Dodgson) paints it as a faintly ridiculous creature, though he reportedly based the animal's stutter on his own speech impairment. Carroll, who was a lecturer in mathematics at Oxford, was almost certainly inspired by the university's own dodo specimen.

Other myths have plagued the dodo over the years. Some got the bird's appearance all wrong, guessing that it was an ungainly, heavy creature and, in defiance of quite a few reports, assuming that it was all-white instead of sporting gray feathers. A few writers and researchers in the earlier parts of the dodo story even doubted that the bird existed, suggesting that it was yet another tall tale told by bored or simply mistaken sailors.

Bringing the dodo back is a hotly debated topic

By the time of the Victorians, the tale of the dodo had become tinged with guilt. It was painfully obvious that had it not been for human encroachment into the environment of Mauritius, the species could have remained happy and even thriving. But the bird may not be extinct forever — some researchers are discussing a very literal dodo revival. Scientists have sequenced its DNA, and work is underway to revitalize the sort of habitat that the animal once thrived in. That environmental restoration is partially being undertaken by Colossal Biosciences, a biotech company that's floated the idea of using genetic material to bring the species back to life.

Colossal Biosciences has grabbed headlines before for similar big talk about other species, including the thylacine and the wooly mammoth. On that last point, the company has made striking inroads, including the debut of genetically-modified mice sporting wooly mammoth-like fur. No advances like that have been announced for the dodo as of yet.

Meanwhile, others have questioned the rather tricky notion of de-extinction, wondering if it's worth bringing a species back from the grave when so many existing ones are hanging on by a thread and could use more immediate help. Are these efforts a bit of duct tape slapped over the rapidly leaking pipe of ecological destruction, climate change, and humanity's role in it all? Or would bringing back the dodo force us to develop tools to fight these bigger problems? That all remains to be seen.