What The Final Year Of Aileen Wuornos's Life Was Really Like

By the time of her execution on October 9, 2002, Aileen Wuornos had been the subject of intense public fascination for the 10-plus years following her 1991 capture. A drifter who murdered at least seven men in Florida in 1989 and 1990, Wuornos was a novelty as a rare female serial killer. Her lesbian relationship, choice of firearm as a weapon, courtroom outbursts, and tragic personal history all contributed to the media circus that followed Wuornos's journey through the legal system.

Even from her cell on Florida's death row, Wuornos continued to capture the attention of an American public that failed to reach a consensus on her: Was she a vigilante, a monster, or simply seriously mentally ill? Her grip on the public imagination hasn't faded since, as she continues to inspire works of art and public debate about her crimes and the justice of her punishment. In the year preceding her death at the hands of an anonymous Florida executioner, Wuornos's circumstances and behavior meant her mystique only grew.

She was held at Florida's women's death row

Wuornos's last residence was Broward Correctional Institution in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. At the time, that's were women on death row were housed. Death row in Florida prescribes a strict regimen, with inmates showering only on alternating days and wearing handcuffs outside their cells, the shower, or the exercise yard. Inmates are allowed radios, small televisions, mail, and magazines, but may not socialize together or sit with other prisoners in the common areas. They wear orange T-shirts to distinguish them from other prisoners at a glance and are counted hourly.

Wuornos had a neighbor for part of her time on death row who was nearly as notorious as she was. Judy Buenoano drowned her son and poisoned both a husband and a boyfriend, among a litany of other crimes including fraud and a car bombing. Her 1998 execution was the first of a woman in Florida since 1848 and proved the state was willing to kill female convicts, though a change in protocol meant Wuornos would be spared Buenoano's fate in the electric chair.

Wuornos had exhausted or abandoned all her appeals

Wuornos had been convicted of six first-degree murders and sentenced to death in each case, along with associated charges of robbery with a firearm, which themselves carried hefty prison terms. These cases were spread out across five Florida counties, further complicating the judicial landscape. Wuornos appealed each case at least once, arguing a variety of points: that she had been mentally incompetent to stand trial, that the courts should have seen she was incompetent at trial, that she had not been advised of the consequences of guilty pleas, that a no-contest plea had not been voluntarily made, that aggravating factors had been overstated, that mitigating circumstances that should have been considered had not been, that her defense counseled her poorly, among others.

Some of these appeals ended in competency hearings, but all found her competent for legal purposes, and none of Wuornos's appeals overturned a conviction or a sentence or led to a new trial on any count. In 2001, Wuornos waived her right to any further appeals. After this, she went through only one more hearing in the summer of 2001 in order to determine her general competency to waive these appeals and her counsel. She was found able to do so, and so her final court appearances explored her competence, not her guilt.

Public fascination with her case remained high

Even more than 20 years after her death, Wuornos continues to arouse intense curiosity and fascination in the public; if anything, the world's Wuornos fixation was even more intense during her incarceration. Movies and books had come out about Wuornos since her arrest, with the killer even receiving the compliment of being played by "Designing Woman" Jean Smart in a Lifetime movie. Summer 2001 saw the premiere of an especially grand piece of media about Aileen's case: the opera "Wuornos," by composer Carla Lucero. Lucero felt she understood Wuornos, commenting to the Advocate that "... there were elements to Wuornos that were true and good."

During her stay in prison, Wuornos continued to receive both admiration and scrutiny, with some people trying to claim her as a feminist heroine and others identifying her as a unique face of evil. Advocates sought her release, and some people visited the bar where she had her last drink, the Last Resort in Port Orange, Florida. People, mostly women, wrote to her, anxious to connect to the strange woman at the center of the storm. Arguably, Aileen Wuornos herself was lost in this maelstrom of dark fame, overshadowed by a legend she had not intentionally created.

Many people thought she was too mentally ill for execution

Aileen Wuornos had, bluntly, never seemed particularly stable, and her erratic behavior in court only made her seem more irrational. Most famously, she vented dramatic and shocking outbursts at trial, referring to one jury as "scumbags of America" and wishing violence on judges and attorneys. Her counsel presented the evidence of Wuornos's very difficult life as mitigating factors: she suffered early bereavement, sexual violence, a pregnancy resulting from rape when she was 14 (the baby was given up for adoption), and a laundry list of other serious traumas.

Because of Wuornos's past and her clear problems with emotional regulation, some experts and spectators felt she was not competent to stand trial. In the last year of her life, Wuornos wrote to the courts to report abuse she suffered in prison, but these claims were clearly the result of delusions, with Wuornos claiming they were shrinking her head (not metaphorically) and cooking her food in dirt. Her own attorneys described her behavior as bizarre and obsessive, fixated on irrelevant details.

As her execution date neared, Wuornos began refusing consultations with both attorneys and mental health professionals. Instead, she wrote more letters to the courts, reiterating her desire to waive appeals and proceed toward her own execution.

Aileen Wuornos was found competent to be executed

Wuornos's concerning behavior and her unusual decision to waive appeals, along with the expressed concerns of some of her lawyers about her ability to act in her own interest, led Florida Gov. Jeb Bush to have her competency assessed again. Bush placed a stay on Wuornos's execution on September 30th so an eleventh-hour examination of Wuornos could be conducted.

A panel of three experts met with Wuornos specifically to see if she met the criteria Florida required for someone who was to be executed: did she know why she had been sentenced, and did she understand a sentence of death? These three examiners did not previously know Wuornos and had not familiarized themselves with her (presumably extensive) file before meeting with her for a mere 30 minutes. Her attorneys objected that the time allotted was too short, especially given Wuornos's current diagnosis of borderline psychosis: she might appear "sane" at some times but slip into psychosis or irrationality under stress.

The 30-minute window stood, and the experts found Wuornos competent for execution purposes. Bush lifted the stay and allowed Wuornos's case to proceed toward the death chamber. An outside attempt by an advocacy group to intervene on the grounds of Wuornos's apparent and seemingly severe mental illness was disallowed by the courts.

She listened to a lot of Natalie Merchant

One of Wuornos's comforts during the last year of her life was the song "Carnival" by singer-songwriter and 10,000 Maniacs alum Natalie Merchant. Wuornos apparently listened to Merchant's entire 1995 album "Tigerlily," but it was "Carnival" that caught her attention, and Wuornos requested the song be played at her funeral. The thoughtful and evocative song, inspired by Merchant's arrival in New York City after a small-town childhood, references "misfit prophets," "cheap thrill seekers," and poverty, with a questioning chorus that asks if the narrator has understood what she's witnessed in the carnival of life: a perfect if poignant fit for Wuornos's difficult life with lyrics that repeat the idea of what the singer's "eyes had seen" as she "walked these streets."

Asked about the situation, Merchant said "If it gave her some solace, I have to be grateful," via Bustle. For many people, the song's legacy is inextricable from that of the notorious, troubled Aileen Wuornos.

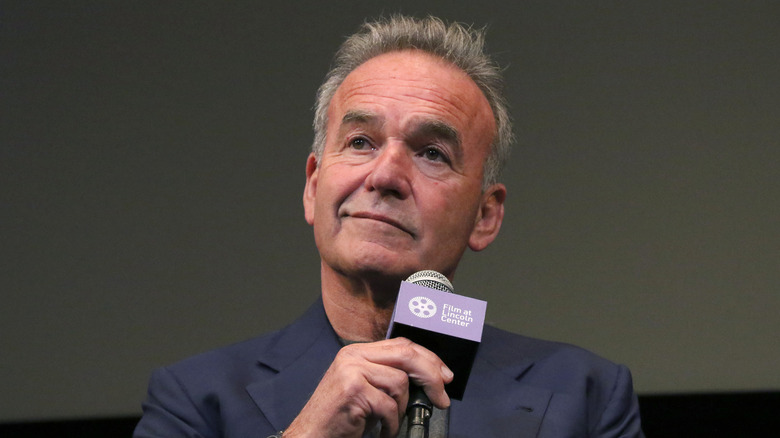

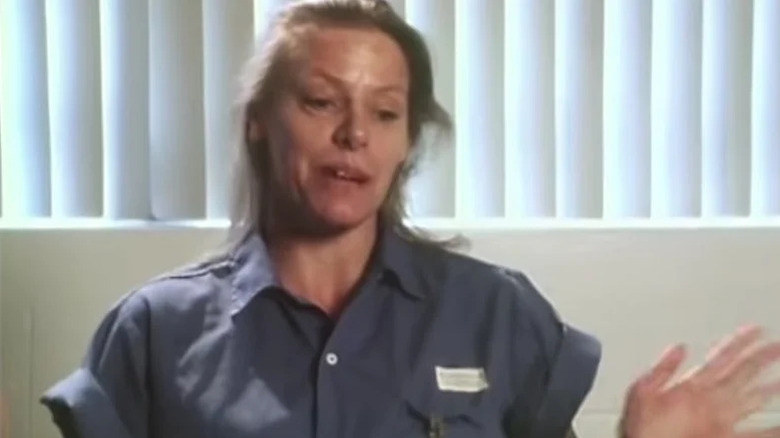

Wuornos gave her last interview to a documentarian

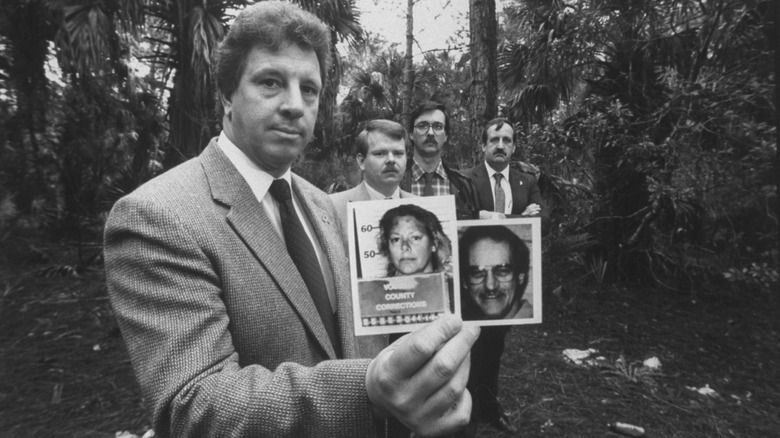

Wuornos was the subject of two documentaries by filmmaker Nick Broomfield. "Aileen Wuornos: The Selling of a Serial Killer" came out in 1992, shortly after her trials. "Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer" was released in 2003, following her 2002 death. The documentarian and the serial killer wrote to each other in the years after Wuornos's trials, and Broomfield was called to one of Wuornos late appeals in order to show clips from "The Selling of a Serial Killer" as evidence. The footage he captured of her attorney (whom she had chosen from a TV ad) smoking marijuana before consulting with Wuornos was insufficient to get her new trials, as were the revelations in the documentary that police involved in her case were angling for Hollywood deals.

It was Broomfield who was last to interview Wuornos. In the interview, though Wuornos is visibly suffering from various delusions, she states that her shocking recantation of her self-defense argument was itself a lie: she had (she believed) killed in self-defense, but after 12 years in prison, she preferred death. Broomfield's other interviews, of people in Wuornos's life who could shed more light on her nightmarish childhood, emerged as part of the Wuornos story. Roger Ebert's review of the film argues that had the child been cared for, the woman would not have killed.

A film about her life was in the works

Director Patty Jenkins' "Monster," the silver-screen treatment of Wuornos's life, had its American release in December 2003, some 14 months after Wuornos's execution. The film stars Charlize Theron as Wuornos and Christina Ricci as "Selby," a lawsuit-avoiding version of Tyria Moore, Wuornos's lover during the final period of her life outside custody. "Monster" was shot on location in the Florida towns Wuornos moved and killed in, immortalizing some of the rougher parts of Florida as they looked a mere decade after Wuornos hit headlines.

Theron, who produced the film and whose weight gain and dental prostheses made her the image of Wuornos, beat out Kate Winslet and Heather Graham for the role of Aileen Wuornos. Despite the film's subsequent success and praise, distribution proved difficult, given the extremely bleak topic, but Newmarket Films struck a deal with Jenkins and Theron shortly before they were going to send it straight to video. Theron went on to win a Best Actress Oscar for her role — an accolade awarded to her on February 29, Wuornos's birthday. Perhaps a greater laurel for Theron was that Nick Broomfield, who knew Wuornos well, praised Theron's performance, even as he criticized the exclusion of the real-life Wuornos from much of the conversation around the film.

She remained difficult to classify

Wrongly but persistently, Aileen Wuornos was presented to the world as its first female serial killer. (Her less sympathetic predecessors in crime, Indiana hatchetwoman Belle Gunness and Hungarian torturer Elizabeth Bathory among others, might like a word.) Her gender was key to the public's fascination: the two motives imputed to her, hatred and greed, weren't "feminine." Feminist scholar Phyllis Chesler, who wrote to Wuornos and has written several works about her, notes that not even in fiction did a comparable murderess exist. Wuornos was wild, sexual, and above all, furious. A cultural example of a woman who was so angry, and who acted on this anger, did not exist, and this lack goes some way to explaining Wuornos's folk-hero status to some.

Chesler points out that Wuornos inverted the usual pattern of violence. If a murder involved a sex worker, it was usually the woman selling her favors who died. A dangerous sex worker was a rarity. To further elaborate her points, Chesler compares Wuornos to Ted Bundy, another notorious murderer tried in and killed by Florida. Bundy received a requested change of venue, unlike Wuornos, and his jury took longer than Wuornos's both to convict and to recommend death, even though Bundy had no mitigating self-defense claim or abuse history comparable to those of Wuornos.

Chesler's thesis is ultimately that Wuornos doesn't fit the molds offered to her: she's neither quite like a male serial killer nor wholly like the female abuse victim who snaps. A 2005 article in the Journal of Forensic Science agrees, writing that while Wuornos was psychopathic, whether she was sexually gratified by the murders remained ambiguous. Wuornos, to her detriment at trial, was in a category all by herself.

Wuornos described herself as ready to die

After 12 years in custody, 10 of them on death row, and a troubled life overall, Wuornos was ready for her troubles to end. Bitter with a weak tether to reality, Wuornos wrote to her friend Dawn Botkins that she would miss Botkins and a handful of other people, but that otherwise she hated the world and was ready to leave it. A prison guard noted in a Guardian report that Wuornos was prepared to die in order to exact a degree of revenge: "... she can't wait until Wednesday at 9:30 so she can be with her God and punish all the evil-doers for the way they treated her."

Wuornos's willingness, even eagerness, to die even in the far-from-comforting venue of the Florida death chamber unsettled some observers. The same Guardian report quoted an anti-death penalty advocate as describing Wuornos's execution as "a state-assisted suicide." Wuornos herself made a grimly utilitarian appeal for her death: keeping alive someone like her, who had threatened to kill again, would be "a waste of taxpayer money."

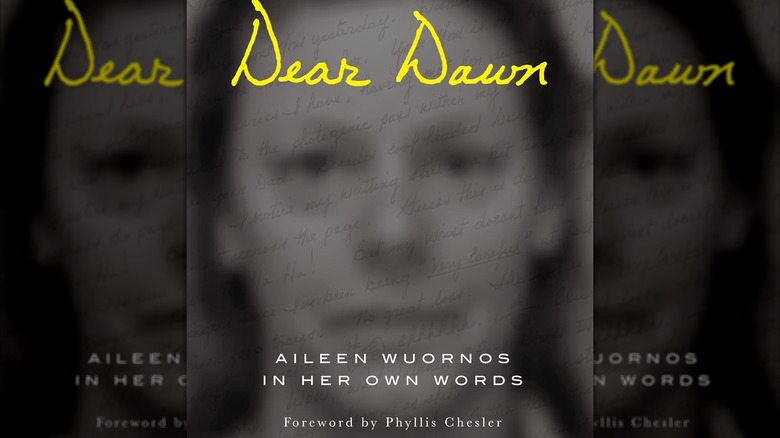

Wuornos kept writing to an old friend

Those sympathetic to Wuornos will be relieved to know that she kept in touch with an old friend during her time on death row. Dawn Botkins had grown up with Wuornos in Michigan, later telling an Oxygen documentary crew that despite her extremely troubled youth, Wuornos seemed "perfectly normal" to her when they were young. When Wuornos was in prison, she wrote to Botkins, sometimes multiple times a day, viewing Dawn as a safe outlet and her only real friend.

Wuornos's letters to Botkins were collected and published under the title "Dear Dawn: Aileen Wuornos in Her Own Words." Wuornos signed her letters to Botkins as "Lee," and the portrait of Lee that emerges is highly varied: Wuornos's rages and delusions are present, but so are happy memories of those she loved. (Wuornos was apparently a cat person, among everything else.) Wuornos writes a lot about Christianity and "Star Trek," as indeed many people probably have, but excerpts available online only underscore the argument that at the end of her life, Wuornos was a seriously mentally ill woman who likely did not totally understand her circumstances.

She declined a last meal and gave cryptic last words

Aileen Wuornos was executed on October 9, 2002. Jeb Bush, then the governor of Florida who signed Wuornos's death warrant, was criticized in some corners by those who suspected he was pushing ahead with the execution to score political points ahead of a November election. Wuornos was entitled to a last meal but turned down the offer, asking only for a cup of coffee.

Wuornos's recorded last words did nothing to comfort observers who feared a legally insane woman was being hurried to her death. Conflating science fiction and Christianity as she often did, Wuornos stated, per the Independent and other outlets: "Yes, I would just like to say I'm sailing with the rock, and I'll be back, like "Independence Day," with Jesus. June 6, like the movie. Big mothership and all, I'll be back, I'll be back." ("Independence Day" as in the Will Smith movie, it's generally assumed.)

Wuornos died of lethal injection at 9:47 that morning, the 10th woman executed in the United States after the re-establishment of the death penalty in 1976. Her ashes were given to her friend Dawn Botkins, who scattered them under a walnut tree on her property in Michigan, where the women had grown up.