7 Ancient Weapons Created From Outer Space Materials

Space swords: Could anything be cooler? Or space spears, space arrows, space maces — you get the idea. So are we talking a blade blazing with the enflamed light of the 10,000 fallen gods of Zilrok X? Back when Emperor Hanashash the Ensorcelled fell to the legions of Thraxar the Mighty in the three-centuries War of the Black Sun? A blade able to slice clean through a planetary hemisphere and jettison core matter across the vast emptiness of the void? Okay, maybe not. But terrestrial weapons made from meteorites? Sure.

While ancient space weapons might not be as cool as what we described above, they're still cool. "Behold, I hold in my hand a blade forged from stone fallen from the heavens!" an ancient ruler might have proclaimed. And that person would have been correct. The materials used in such weapons — typically iron and nickel — came to Earth, survived entry into our atmosphere, landed, got discovered, smelted, shaped, and bam: We get headlines about cool archaeology.

Ancient weapons made from space stuff aren't exceedingly common, but they're more common than you'd think. Ninety to 95% of the material that reaches our atmosphere is small and burns up on entry. According to NASA, Every 2,000 years or so, a meteorite the size of a football hits the surface. And then there are big, extinction-level rocks like the Chicxulub impactor that annihilated the dinosaurs about 66 million years ago. But all together, we've got a decent amount of weapons made from meteorites: a dagger buried with King Tut, a knife belonging to the Mugal Emperor Jahangir, random arrowheads in Switzerland, and more.

Pharaoh Tutenkamens' celestial burial dagger

What do you get for the boy who has everything? Okay, the "boy king" of Egypt, Pharaoh Tutankhamun, who ruled for about a decade in the 14th century didn't have everything. He was inbred, had inbred kids with his sister, had a club foot from necrotized bone tissue, was generally frail and sick, and was dead by 19. But you know what he did have? A super cool tomb full of gold stuff like sandals, a checkers-like board game, wooden servants, some underwear, and a "gift from the gods" strapped to his mummified thigh, per History. Why from the gods? It fell from the sky and got made into a dagger.

Originally described as a "highly ornamented gold dagger with crystal knob" when first discovered in 1925, per Science Alert, the royal dagger in King Tut's tomb has an iron-and-nickel blade with a decorative golden sheath. Thanks to imaging technology called X-ray fluorescence spectrometry, researchers know the blade is made of 11% nickel rather than typical 4% nickel — this means meteorite.

In fact, researchers went above and beyond by tracking down the exact meteorite from which the blade was formed. Out of 20 known meteorites in a 1,243-mile radius from the Red Sea, Tut's dagger likely came from the meteorite dubbed Kharga. Kharga was discovered in 2000 west of the Egyptian city of Alexandria, which sits at the western edge of the Nile delta at the mouth of the Mediterranean Sea. In other words: It was the perfect spot to mine metal for the boy king. It's possible that Tut had a chance to admire it while alive, but we can't say for sure.

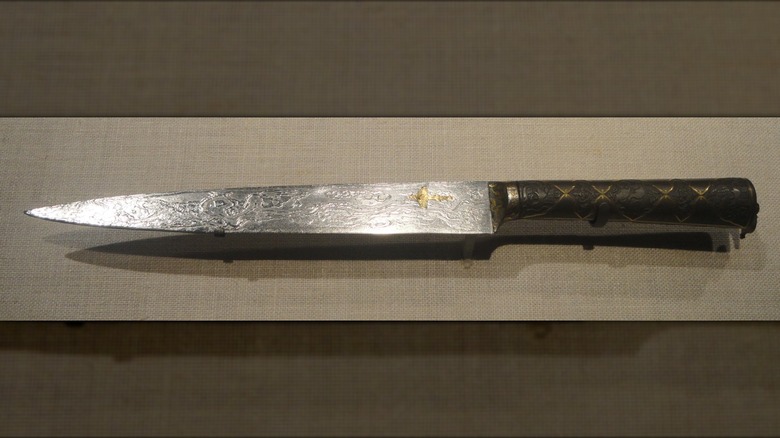

A dagger made for the Mughal Emperor, Jahangir

The Mughal Empire illustrates precisely how inadequate modern maps are at describing the flow of past peoples, cultures, and civilizations. Lasting from roughly 1526 to 1761, then breaking off into states that lasted until the British took control of things in the mid-1800s, the Mughal Empire covered parts of current-day India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, and left its mark on all those countries. Mughal history comprises a tangled, complex, messy succession of dynastic rulers, regional power struggles, and a mishmash of Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, and more, religious and associated ethnic groups. Nur-ud-din Muhammad Jahangir — "the World Seizer" — was the fourth Mughal emperor (1605 to 1627) who spent much of his rule fighting off rivals. He also had this really sweet space knife.

Said space knife is made from iron, has a gold inlay, a decorative hilt, and dates to 1621. As the Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art says, there's a (presumably very tiny) inscription on the unsharpened spine of the blade that reads, "There fell in the time of Jahangir Shah / From lightning-iron, a lightning-like, precious piece / Jahangir, [son of] Akbar ordered to make of that / Two swords, this knife and a dagger." Jahangir's memoirs, the Jahangirnama, fancifully writes of the meteorite, "At dawn a tremendous noise arose in the east. It was so terrifying that it nearly frightened the inhabitants out of their skins. Then, in the midst of tumultuous noise, something bright fell to the earth from above." Jahangir also said that the blade cut as well as the finest swords.

Inuit and Dorset blades from Greenland

You know what would be really helpful in Arctic places like Alaska, Northern Canada, and Greenland? A knife. A stone knife would be ... fine. But a metal knife would be better. And not just any old knife, but some kind of multi-purpose, animal-skinning, cut-it-all blade that hardy residents can use for anything and everything on a daily basis. And oh, what's that? There are these big rocks that fell from the sky and landed near Cape York, Greenland? And if only you made the trip on foot across hundreds of miles, you could hammer off a piece of the sky rock and smelt it into an ulu (seen above), aka, an all-purpose blade made from space iron? Yes, all of the above is true.

While not strictly "weapons," the knives made from Greenlandic meteorites could definitely slit a throat. The Dorset people would have known this — one of the earliest residents of remote, Arctic, inhospitable places like Greenland. They're the ones who first found the three meteorites – or one meteorite that broke into three pieces — that crash-landed in Greenland after entering Earth's atmosphere about 10,000 years ago. The largest of these three meteorites, Ahnighito, — "The Tent" — weighed 31 tons. Dubbed the "Cape York Meteorites" by 18th-to-19th-century European explorers, Dorset and Inuit people had apparently used the meteorites as their sole source of metal for centuries – if not millennia. Explorers found over 10,000 hammer stones used for breaking off pieces of Ahnighito, alone.

Zhou dynasty Chinese axes

It's time to take a break from space daggers and talk about blades of a bigger type: space axes. Specifically, bronze blades with meteoric iron tips connected to bronze tangs that once connected to now-deteriorated wooden handles. Got it? Discovered in China's Henan Province in 1931 and the subject of a comprehensive, 98-page, 1971 analysis by the Smithsonian Institute, the two axes in question represent the only known instance of meteorite weapons found in China. The broad axe and dagger axe were part of a group of 12 weapons found at a tomb dating to the early Zhou dynasty (1050 to 221 B.C.E.). But, they were the only meteorite weapons in the bunch. And they were ceremonial weapons, not real ones.

As the Smithsonian Institute's report says, the two axes represent an extreme rarity amongst archaeological finds from China. Iron was called "the ugly metal" in ancient China and was reserved for everyday, common goods like plowshares and arrow shafts. Bronze was "the lovely metal" and cast into things like ceremonial vessels used during rituals related to ancestor worship. But, meteorite sightings were a grand and "auspicious" event, one that even took on a selfsame, conventional role in Chinese literature. But to see a real meteorite fall and then collect it to make a grave good for a dead ruler? This opportunity would have outweighed the ugliness of iron and explains why the two axes in question are the only ones of their type.

Lots of Indonesian kris

Next up, a dagger that looks lifted directly from the pages of a human sacrificial how-to manual: the Indonesian kris. Kris (singular and plural) and their distinctive, wavy blades and flintlock pistol-like hilts occupy a special place on our list of ancient space weapons. By definition, a kris of true power is made from a meteorite. Think: "I must go on a quest to forge a sacred dagger with a core of space iron and nickel" and you've got the right idea. Kris lore and smithing is so wildly cool and unique to Indonesia that kris have made the UNESCO Intangible World Heritage. As UNESCO summarizes, kris serve as, "talismans with magical powers, weapons, sanctified heirlooms, auxiliary equipment for court soldiers, accessories for ceremonial dress, an indicator of social status, a symbol of heroism," and more.

Sadly, not all kris contain meteorite core. But kris makers — empus — know how to smith the iron and nickel into the blade, rare as such skills are nowadays. As a study from the Natural History Museum in Austria shows, the blade starts with a thin rod of nickel-iron in the center surrounded by regular iron. The blade gets stretched out, flattened, and eventually made wavy.

Nowadays, many true meteorite-core kris rest in museums. These and others came from select meteorites, like one that fell at the site of the 9th-century Prambanan Temple on the island of Java in 1750. That meteorite was carried to the sultan's palace in the nearby city of Yogyakarta.

A dagger from a royal tomb at Alaca Hüyük, Turkey

This next meteorite dagger is actually the oldest ancient space weapon on our list — about 1,000 years older than King Tut's dagger. This dagger comes from the ancient Hittite settlement at Alaca Höyük in North Central modern-day Turkey and has an iron meteorite blade and golden hilt. Like many of the other weapons in this article, this item was a grave good buried amongst royal tombs and never intended for use in combat. Interestingly, while the dagger dates between 2400 and 2300 B.C.E., the Hittites occupied the region from about 1700 to 1200 B.C.E. So there's really no way to know if the dagger is Hittite made, before they dominated the area, or if it was inherited from somewhere and someone else.

Objects this ancient tend to throw our historical timeline into disarray, and the Hittite dagger is no exception. Commonly accepted historical wisdom places the Iron Age from 1200 B.C.E. to 600 B.C.E., following the much longer Bronze Age from 3300 B.C.E. to 1200 B.C.E. The rollover from bronze to iron came with better (and hotter) smelting and forging technology. That being said, folks knew about and worked with bronze as early as 6500 B.C.E. in Anatolia, aka Asia Minor — the same region as modern-day Turkey and the Hittite dagger. There's also evidence of iron beads in Egypt dating back to 3500 B.C.E. But the dagger at Alaca Hüyük? Its craftsmanship is exceptional and obvious even taking its decay into account, and speaks to the advanced skill and know-how of its makers.

Arrowheads from Bronze Age Switzerland

Finally, we end on a space weapon that didn't belong to a buried royal, but ranked amongst the most commonplace of items you'd be liable to find in ages past: arrowheads. In what is another discovery that upends assumptions about the past, researchers from the Natural History Museum of Bern, Switzerland found meteorite arrowheads in the region of Mörigen, modern-day Switzerland, along the eastern coast of Lake Bier. Arrowheads of this type aren't super uncommon, and date to about 900 to 800 B.C.E. Peoples of the time often turned to meteorites as a source for iron. What's more uncommon is where the iron in these arrowheads came from.

As Science Alert explains, researchers X-rayed the arrowheads to take a look at their composition and found that regional iron meteorite doesn't match the iron meteorite in the arrowhead. The arrowheads' iron comes from silicate-heavy IAB meteorites, the type which landed in only three regions across Europe: Retuerte de Bullaque, Spain; Bohumilitz, Czechia; and Kaalijarv, Estonia. By all accounts, it seems like the Swiss arrowheads came from the Estonian meteorite, which landed about 1,500 B.C.E. and blasted apart into fragments.

The point is this: The Estonian meteorite is about 1,000 miles away from Switzerland, a long, long journey traverseable only by merchants along some well-worn trade route. The Amber Road, which spread amber from Western Russia through Western Europe, is a good option. Basically, like we've learned this entire article: Never discount ancient peoples' cleverness, craftsmanship, and tenacity.