Why The Crusades Were Worse Than You Thought

The number of Crusades and how long they lasted depends almost entirely on what you feel like counting as a crusade, but even the most conservative accounting adds up to centuries of bloodshed and countless dead. Christian armies streamed out of the kingdoms of Western Europe in order to reconquer the Holy Land and various attractive or convenient territories nearby; later Crusades focused on mopping up remaining pockets of paganism in Europe, stamping out religious movements considered heretical, and eradicating the last Muslim kingdoms in Southern Iberia.

These long-lasting and complicated conflicts led to enormous human suffering. While many of the people involved fought because of genuine religious fervor, others were more calculated, with popes and emperors coldly evaluating the advantages to be gained in the advancements of armies and the ruin of cities. For their part, the common soldiers involved at times committed unfathomable atrocities, often made easier by the "infidel" status of those on the other side. Between the Machiavellian motives underlying them and the horrors they unleashed, the Crusades were far worse than many modern people realize.

The Crusades began with ulterior motives

The Crusades are often described as a Christian attempt to "retake" the Holy Land, but this is an oversimplified take. Jerusalem had fallen to Arab armies in 638; the First Crusade set off in 1095, so the Christian holy sites in the Levant had been under Muslim control for generations. What changed was the rise of the Seljuk Turks, a former steppe tribe that had adopted Islam and, perhaps more to the point, beaten the absolute snot out of the Byzantine army at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071. When the Seljuks began gobbling up the Eastern Mediterranean coast, including Jerusalem, in the years after Manzikert, the Byzantines saw a way they might argue to Western European powers that they should help fight the Seljuks.

This argument found a receptive ear attached to the head of Pope Urban II. Of course, the retaking of the Christian holy sites was arguably a religious duty, but if the papacy organized such an effort, the office would gain enormous prestige. Urban wanted to consolidate his position against both the Holy Roman Emperor, traditional political rivals of the papacy in Italy, and against the Eastern Orthodox Church, which had split from Rome in 1054. If the Roman papacy brought Jerusalem "back" under Christian control, Urban and his successors would have an undeniable token of divine favor.

The Crusades lasted a long time

While the exact accounting of the number of Crusades and thus the duration of the whole gory project will vary according to which historian you ask, even the most constrained period is pretty long. Pope Urban II preached the beginning of the First Crusade in 1095, and in 1097 the initial Crusader armies took their first major city, Nicaea, and won their first major battle, at Dorylaion. Antioch followed in 1098, and the big prize, Jerusalem, fell to the Christians in July 1099.

You can take your pick of events that marked "the Last Crusade." Christian forces lost Jerusalem again in 1187; the remainder of the optimistically-named Kingdom of Jerusalem fell in 1291. Scuffles between Christian and Muslim powers continued, notably, a terrible sack of Alexandria by the king of Cyprus in 1365. An anti-Ottoman "Crusade of Nicopolis" failed catastrophically in 1396. Ferdinand and Isabella, whose marriage united Spain, positioned their conclusion of the Reconquista of the Muslim south of Iberia as another Crusade, ending with the fall of Granada in 1492.

Calls for Crusades and events billed as such declined in the following century. The rising Protestants were, shall we say, less susceptible to papal instruction, and the potential riches of the Americas refocused much of Europe's attention.

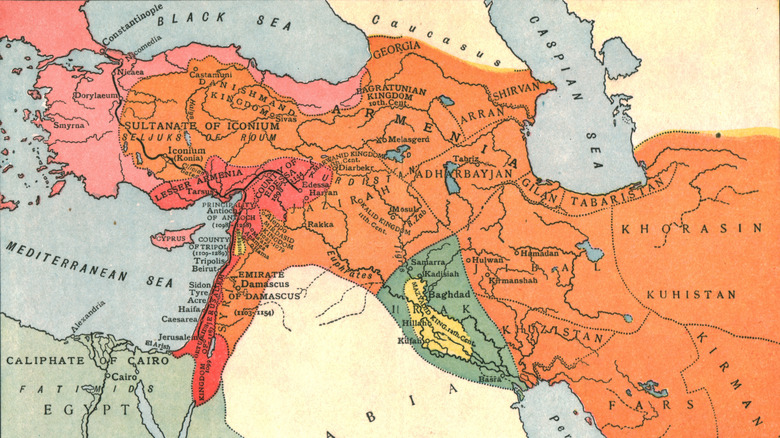

They occurred over a wide area

The Crusades sprawled out over a huge area. While the actual "Holy Land," defined for convenience as today's Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories, is marginally bigger than Massachusetts, the Crusades didn't confine themselves to this territory. The realities of supplies and transport meant both that the First Crusader army needed to go overland from Byzantine territory and that they didn't want to set up an isolated little outpost if and when they did get to Jerusalem. Instead, Jerusalem was the southernmost of a spray of Christian states that included the entire coast from the Byzantine Empire to Egypt, extending inland to incorporate chunks of modern Syria and Turkey.

But wait, there's more! The Crusaders also helped themselves to Cyprus and tried very hard to take Egypt. The Fourth Crusade went completely off the rails and savaged Constantinople. Other Crusades within Europe were called against pagan tribes along the Baltic coast, proto-Protestants in Bohemia, Muslims in Spain, and heretics in Southern France. If you wanted to go somewhere interesting in order to kill people who followed a different religion, the church had a crusade for you!

Crusader armies were often underprepared

For all its fascinating history, cultural riches, and oil wealth, the Middle East has seldom been considered an enormously productive agricultural area, which is a problem if you want to move an army across it. Medieval armies generally lived off the land, which is a polite way of saying that they foraged and stole from people they encountered, but the hotter, drier Levant made this approach more challenging. Captured cities were a potential source of supplies but, as the crusading army learned to its dismay after taking Antioch in 1098, sometimes the people inside the city had eaten everything, especially if they had just been subjected to a siege that cut them off from their regular sources of supplies.

An especially grim example of bad supply availability leading to bad outcomes occurred at the Battle of Hattin in 1187. A Crusader army heard that the great general Saladin was advancing on Tiberias, on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, so moved quickly to intercept him ... across arid land where they suffered initial attacks from enemy cavalry and, even worse, ran out of water. (Remember, horses drink too.) The parched Christians spent the night without access to water: unable to fight well the next day, and they were slaughtered. Saladin's forces captured a piece of the True Cross the Crusaders had carried, and later that year they rode the momentum of Hattin into Jerusalem.

There was a Children's Crusade

One of the many failings of the human species is that we often fail to protect children from war. Sometimes we even force them to participate or fail to intervene effectively when they try to involve themselves, as occurred with the Children's Crusade of 1212. Pedants argue that the outbreak of kids involved in mass hysteria, popular enthusiasm, or irrational optimism about how to fight a war was not strictly a crusade, as only the pope could call a crusade, and he didn't in this instance. Additionally, the Latin word "pueri" can mean boys but also landless people, so how young these participants were is not totally clear. Nevertheless, this event did involve children trying to go crusading, so "Children's Crusade" it is.

Medieval records are seldom especially good, but what seems to have happened is that papal attempts to rouse an army against the Cathars in Southern France got some young French people all worked up, so they went in a disorganized group to the Rhineland. There they were probably absorbed into a group of German children who had become similarly optimistic about God's plans for medieval kids and walked to Northern Italy.

When the expected parting of the Mediterranean failed to occur and procuring ships proved impossible (imagine being asked to run these children to Israel real fast), some of the little Crusaders took a ship to Marseilles, while others pressed on to Rome to ask the pope to release them from vows he had not asked them to take. Most of the participants died or were enslaved, but their zeal did inspire Innocent III to call the Fifth Crusade the following year so that some adults could get back to marauding in the East.

The Crusades caused antisemitic violence

As the first Crusaders organized themselves to head toward the Middle East, one of them had a terrible, fateful brainwave: why wait until they arrived abroad to start killing people when they had non-Christians much closer to home? From this sinister idea rose a wave of violence against Jews, which was especially savage in the cities of the Rhine valley: in Worms and Mainz, effectively the entire Jewish communities were obliterated. Historians estimate that as many as 10,000 of the Jews of Europe died in bloody 1096. Whether these massacres were driven "just" by existing antisemitism, resentment of Jewish moneylenders, general apocalyptic sentiment, and/or frustration at failed attempts to convert them as part of the crusading project remains debated.

The Jews of Jerusalem didn't fare much better. In 1099, the Christians were expelled from the city as the Crusader army approached, but the Jews were allowed to stay — a consideration they would come to regret. When the Crusader army punched into the city, they accepted a ransom from the Muslim governor to spare his life and those of his guards before setting about killing everyone else they could catch. Considering the Jews as collaborators with the Muslims, the city's Jewish population perished alongside their Muslim neighbors in the vicious sack. Chronicles vary in their estimates, as always, but the lowest figure offered for combined Muslim and Jewish dead in the savagery is 3,000 of a population of about 30,000.

They killed fellow Christians

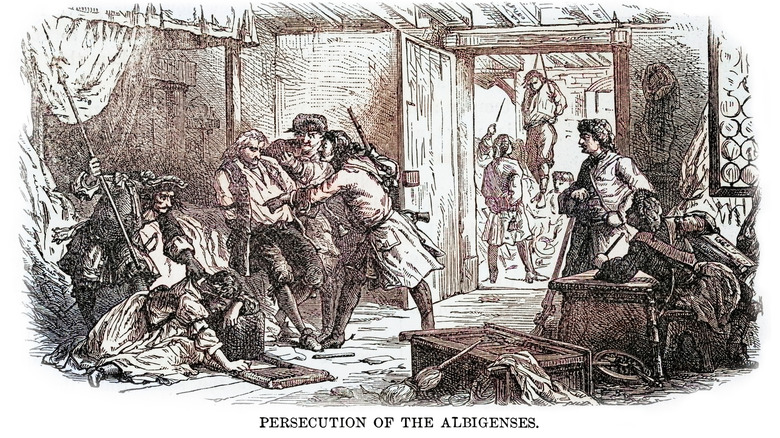

While the initial Crusades had been called against Muslim powers, the willingness of the Crusaders to go off-book and include Jews in their violence presaged the violence they would eventually turn even on their fellow Christians. Popes concerned with heresy — and of course, one person's heresy is another person's completely valid religious movement — found they could call Crusades against people who were doing Christianity wrong.

The best-remembered (though far from unique) example of a crusade against Christians was the Cathar crusade in Southern France. The Cathars (or Albigensians) believed in simplicity, equality of the sexes, and rejection of the trappings of the world ... along with some unorthodox ideas, like reincarnation, that much of the Bible had been written by Satan, and that sex for pleasure was perfectly valid. Cathars also critiqued the Roman church for its accumulation of wealth and general worldliness, a criticism that may strike readers as familiar.

Confronted with this challenge to Catholic supremacy and doctrine, the ironically-named Pope Innocent III launched a crusade against the Cathars and their protector, the Count of Toulouse, in 1209. Like warmongers before and after him, the pope was able to weaponize greed, promising the nobles of Northern France they could keep what wealth they stripped from the South if they but crushed the terrible sex-having vegetarian heretics infesting the region. Crush they did: Toulouse was surrendered to the French crown and thousands of Cathars were massacred, ending in a final mass burning after the fall of their last stronghold, Montségur, in 1244.

Crusaders could attack the wrong city

In 1204, a Crusader army notched a shocking victory, taking and looting a powerful and wealthy city that had resisted all attempts to take it for centuries. Unfortunately, this city was the Christian city of Constantinople, the seat of Eastern Christianity and the capital of the Byzantine Empire.

In 1202, Pope Innocent III called for an attempt to retake Jerusalem, lost in 1187, and the Crusading force gathered in Venice, then the center of a powerful state. Complex Venetian wheeling and dealing led to the Crusaders attacking Christian Zara (now Zadar) on the Adriatic coast; the enraged pope excommunicated the Venetians, who proceeded to commit an even more shocking series of sins. (It was so bad that John Paul II apologized to the Greeks in 2001.) Venice's leader, a very old and greedy man named Enrico Dandolo, disliked competing with Constantinople for trade and managed to swing the Crusader army into a conquest and looting of the ancient city. (The famous horses of St. Mark's Square in Venice were stolen from Constantinople at this time.)

The riches of Constantinople were allegedly going to finance the conquest of Jerusalem, but they did not. The triumphant Venetians carved up the Byzantine Empire into a set of smaller kingdoms that spent most of the next century congealing back into a restored Byzantine Empire, just in time to be slowly whittled away by advancing Turks. The Crusader states in the Middle East received no help and continued their own slow dissolution.

Countries with absent rulers suffered ill effects

For a certain kind of man, going on a crusade was way more fun than staying home and ... you know, working. Even if the job they were avoiding was "king," some men preferred to noodle around the Near East killing people to staying at home and governing people. Louis IX, of "St. Louis" fame, went on crusade twice. The first time he had to scurry home after his mother, who had been running things, died; the second time, he himself died after invading Tunisia at the old-for-the-time age of 55. Fortunately, his son was the capable Philip III. Unfortunately, Philip was with him in Africa and had to skedaddle to Paris as soon as his father was cold. While France avoided major calamity during these empty-throne moments, it was largely due to luck. England was less fortunate.

On his way home from the Crusade in 1192, Richard the Lionhearted, king of England and one of the most powerful nobles of France to boot, was shipwrecked and decided to travel overland. The Duke of Austria caught him and handed him over to the Holy Roman Emperor, whose eyes turned into little dollar signs. The emperor held Richard for ransom for 150,000 silver marks, which doesn't seem like much for a king until you hear that it was three times the annual budget of the entire kingdom. Richard's mother, medieval grande dame Eleanor of Aquitaine, put the screws to the English and raised the money. Dumping all that silver into Germany was no boon for the English economy, but at least Richard didn't learn anything. He died fighting in France five years later.

The Crusades were not a lasting success

While it's generally unfair to judge people from the past by today's standards, let's do it anyway: what did the Crusades achieve? For all the blood and treasure spent, Jerusalem was in Western Christian hands for less than a century, and in a few decades more, the remaining Crusader states had all been swept away. Jerusalem would remain under Muslim control until World War I, falling to a British invasion in 1917. The current status of Israeli control contested by an occupied Palestinian state divides opinion worldwide and does not appear indefinitely stable to any but the most starry-eyed optimists.

With Byzantium fatally weakened by Venice's antics in the Fourth Crusade, a moribund state was in charge of Europe's southeastern edge. Before and after they took the city in 1453, the Muslim Ottomans expanded into Europe, foiling Venice, smashing Hungary, and besieging Vienna twice. Popes kept squabbling with Holy Roman Emperors, and despite occasional feel-good photo-ops, the Eastern and Western churches remain divided, with the Crusades having failed to address the causes of the original rift.

Some historians do point to indirect cultural and practical advances from the Crusades, especially for Europe: the size of the undertakings required complicated financial maneuvering, and some Italian cities that were able to advance money and supplies became rich. Plus, the apricot arrived in Europe, and innovations in warfare and construction emerged. Whether these were worth the centuries of war depends, ultimately, on how much you like banks and apricots.