Strict Rules Freemasons Follow

The modern form of Freemasonry emerged from the old occupational stoneworkers' guilds of the Middle Ages. As general trends in construction turned away from the colossal stone cathedrals that had required a steady flow of working stonemasons, some of the individual guild chapters hit on the idea of allowing non-masons to join in an honorary, yet fee-paying and thus helpful, capacity. Because men are just little boys who grew up, some of these groups then adopted rites and rituals from old religious and chivalric organizations, cloaking the whole thing in secrecy for an additional frisson of excitement.

Since the emergence of this more recent, secret-club Freemasonry in the 17th and 18th centuries, Freemasons (often just called Masons) have developed a not unreasonable reputation for secrecy, as well as finding themselves at the center of any number of conspiracy theories. While secrecy about private rituals is one of the rules of effectively all Masonic lodges, keeping the group's secrets is only one of a number of strict rules followed by Freemasons in good standing.

Meet the basic requirements

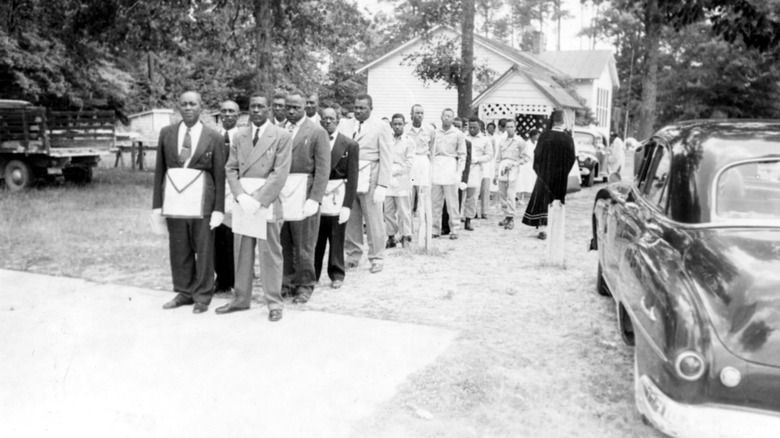

To join a lodge, a potential Freemason must meet a number of formal requirements. The most basic of these is that he be an adult man, though a small number of lodges admit (or are specifically for) women, especially those in France. Additionally, some organizations in the greater family of Freemasonry admit or cater to women and/or young people. Additionally, a Mason must believe in a "Supreme Being" and the immortality of the soul, though the exact form these beliefs take is generally left up to the individual Mason. Racial and/or ethnic backgrounds are theoretically not grounds for exclusion, though some lodges have historically fallen short of this ideal, and American lodges are often still divided along racial lines.

Applicants must also generally be attractive to the lodge: they must be of "good moral character" and driven by a genuine (positive) interest in Freemasonry, not the hope of personal gain, although some lodges reserve the right to ask for a background check. Aspiring Masons must apply of their own volition and with the intent to learn about and partake in the ancient customs of Freemasonry. And they must, of course, agree that if they are accepted into this society, they will follow its rules.

Believe in a Supreme Being

The Masonic requirement to believe in a Supreme Being is intentionally vague, as the Masons are not a religious organization and do not generally discuss religion when they meet. Theoretically, this doctrinal flexibility opens membership to anyone following a theistic religion or privately believing in God, although some lodges have historically excluded those not of the local majority religion. Indeed, an irony of Freemasonry is that some lodges have excluded Jews, even as the movement as a whole has sometimes been accused by those with anti-Semitic beliefs or agendas of colluding with or being controlled by Jewish-led conspiracies.

Discussions among Masons today wrestle with the exact parameters of this requirement. In an increasingly secular world, some lodges no longer enforce this requirement, and there are debates about whether ideas of energy and a generalized spirituality are sufficient. An anecdotal report concerns the complicated case of a modern man who worshipped the old Norse pantheon and considered Odin the Supreme Being in whom he believed. The lodge to which he had applied requested advice from higher-ups and decided that Odin didn't fit the bill, as he was insufficiently "supreme" among his sibling gods. This appears to be a relatively rare situation, with others reporting that when asked, they simply answered "yes."

Adhere to Freemasonry's core values

Freemasonry's central values, as articulated by the site Be A Freemason, include "integrity, kindness, honesty and fairness" and the "timeless principles of Brotherly love, relief, and truth." Brotherhood is perhaps the most clearly overarching responsibility among active Freemasons, with the idea of mutual support and fellowship in the shared pursuit of self-improvement reiterated within materials for aspiring Masons. An ancillary yet important aspect of this brotherhood is the oft-repeated reminder that Freemasonry or membership in a given lodge is not to be used for gain, either for oneself or for some religious, political, or business aim. Freemasonry is supposed to be about Freemasonry and one's brothers in the organizations.

Another important aspect of the modern Masonic value system is charity, representing the "relief" to be given to those in distress, Masons or not. A number of Masonic lodges have unified charitable foundations to organize such help for lodges in a given area, such as England and Wales or specific U.S. states. The individual scopes and priorities of these organizations vary in priorities, befitting the decentralized nature of much of Freemasonry, and include general grantmaking, eldercare, disease research, and scholarships, among others.

Additionally, many of the organizations in the broader family of Masonic-aligned organizations include service in their group activities and aims. One particularly prominent example is the famously silly Shriners, who support a network of children's hospitals.

Maintain secrecy

Secrecy is probably the concept most closely associated with Freemasonry by outsiders; it is a secret society, after all. Freemasons today share among themselves a wide assortment of secret — and, admittedly, no-longer-so-secret — symbols and rituals, including a good old-fashioned secret handshake. These are not necessarily all the same among different groups of Masons, as Freemasonry is not a completely unified organization, and the odds are that any given secret is itself not particularly important.

Secrets are, however, extremely cool. It has been argued that such secret Masonic knowledge, whether real or not, tempted the curious to join the brotherhood and make it the old and geographically widespread phenomenon it is today. The secrecy in which the Masons wrap themselves can be said to be the key to their mystique, and this enduring mystery may have inspired less savory organizations with very real secrets, like organized crime groups and the Ku Klux Klan.

Some Masons emphasize the secrecy not of any specific ritual or tidbit of information, but of the privacy of the lodge in general. After all, a lot of the Masonic secrets have been published: the only thing harder to imagine than a secret kept for hundreds of years is one kept by millions of people. Instead, the secrecy that's important to today's Masons is the discretion offered to their fellows about what they discuss and disclose in meetings. If Masons no longer keep esoteric secrets, each still may hide the private revelations of his brethren.

Wear the correct clothing

The Masonic ideal of equality within the lodge and of a generally egalitarian brotherhood extends to dress within the lodge. In order to avoid the faux pas of standing out or seeming excessive or showy, most Masons will choose a dark suit for formal lodge occasions, with black not being required but always a popular choice. This goes with a dark tie, a dark pair of shoes, and a white or light-colored shirt to create a neat and conservative appearance, which individuals can jazz up a bit with Masonic accessories like rings or watches.

This basic look is accentuated with the famous Masonic regalia: aprons, collars, and for high-ranking Masons, hats. The apron is the piece that perhaps most recalls the Freemasons' origin as a stoneworkers' guild: they still follow the basic design of the useful worker's garment, now with the symbolism of building good lives instead of imposing structures. Beginners' aprons are traditionally white lambskin, which is changed for more distinctive designs upon the attainment of degrees or offices. In addition to the apron, Masons may wear collars denoting rank or office, but these are not standardized across lodges and vary in design and structure. The Worshipful Master, head of an individual lodge, often completes his regalia with a top hat to mark his office.

Go through the initiation ritual

Aspiring Masons must pass through an initiation ritual known as the First Degree. They begin by approaching the lodge dressed in a certain, symbolically important way. They will have the heel of at least one foot bare, symbolizing that the Masonic lodge is hallowed ground where bare feet are appropriate. Pants legs are rolled up to indicate that the potential Mason has no shackles or related marks, indicating that he is free, and to allow the bare knee to contact the earth when making vows. The left side of the chest will be bare to show that the potential Mason is not a woman in disguise, and the right arm will be similarly exposed to prove that the initiate has not come with a weapon. In some instances, applicants are blindfolded and led with a rope around the neck.

When a potential Mason arrives correctly dressed and prepared, the lodge tyler (door guard) knocks three times on the door so the initiate can enter. The initiate will have a dagger pressed against the bare side of his chest (gently, one assumes) to underscore the seriousness of the undertaking. He is then led around the interior of the temple and asked a series of questions, most of which he will answer with the assistance of a Junior Deacon. That help in the first stage of a Masonic journey symbolizes both the support a Mason will need and the trustworthiness of his brethren-to-be. He will then kneel and take his oath as a Mason before standing with feet squared in the northeast corner of the room, recalling the position of the foundation stones his predecessors laid so many of.

Petition for entry

A common misconception is that a man must be explicitly invited by an existing Freemason to join, but this is not true. In fact, the etiquette is that existing Masons may hint ("I think you'd be a good Mason!") but will not go so far as to extend an invitation: the desire to enter the fraternity must come from the aspiring Mason, not from anyone else. From there, a potential applicant must make a formal petition for entry, generally to a particular lodge; the lodge will then investigate the applicant and vote on his entry. Chillingly for anyone picked last in kickball as a child, this approval must be unanimous.

Those hoping to become Masons are encouraged to approach their favorite Mason and ask him directly about the organization and the process of joining it. Additional options include going directly to a lodge or to the overarching Grand Lodge of a given jurisdiction. Contact information for local Masonic representatives is even available online, and some lodge organizations allow you to take this first step by email, a prudent choice in the modern age.

Avoid committing Masonic crimes

In 1855, a prominent South Carolina Mason named Albert Mackey codified the regulations of Freemasonry in general in a work titled "The Principles of Masonic Law: A Treatise on the Constitutional Laws, Usages, and Landmarks of Freemasonry." The magisterial work is organized by topic into four books, the last of which is "Of Masonic Crimes and Punishments." Here, Mackey notes that Masonic crimes overlap heavily with moral wrongs and reiterates that religious or legal crimes are not within the scope of Masonic justice. His examples include heresy and, interestingly for a Southerner in the 1850s, rebellion: an insurrectionist's fellow Masons must disown his rebellion, but cannot eject him from their lodge without additional charges.

Mackey goes on to list some examples of moral offenses, starting with "profane swearing" but quickly escalating through more severe infractions like adultery and murder. (Note that murder is not a Masonic crime because it's illegal but because it is bad in itself.) He clarifies, memorably, that "Whatever moral defects constitute the bad man, make also the bad Mason," before going on to list offenses that are specifically Masonic in nature. These mostly concern behaviors that would disrupt the activities of the lodge or generally harsh the vibe, including arguments, continuing private disagreements or drama within the lodge, "unseemly and irreverent conduct," and, admirably, refusing to help a fellow Mason in need if you're able to do so.

A final section of Freemasonry no-nos refers, unsurprisingly, to secrets of the craft or of one's fellow Masons. Masons may not discuss Masonic business in front of outsiders, spill secrets, or even defend Freemasonry overenthusiastically to outsiders.

Participate in trials

Masons accused of breaking Masonic laws may be subjected to trial. According to the rules laid down in Albert Mackey's "The Principles of Masonic Law," the Masonic trial process begins when an accuser — who need not even be a Mason — transmits a written denunciation to the lodge secretary. The secretary reads the charge at the next meeting, and the assembled Masons will arrange a trial to occur after the accused has had time to prepare a defense. If the accused has moved, the trial can be transferred to his new lodge.

At the trial, both accuser and accused will be allowed to present and question witnesses, which may again include non-Masons who may have knowledge about the situation. After evidence has been given and both sides rest, all other Masons present act as a jury, with a two-thirds majority necessary for conviction. Every jury member present must vote unless excused unanimously by a vote of the other jurors. If the accused is found guilty in a private ballot, show-of-hands votes are then taken on what punishment will be administered, beginning with the most severe and descending in gravity until a majority votes in favor of a given course of action.

Mackey lists five punishments available for Masons to apply to their misbehaving brothers; all but the mildest, censure, require a formal trial. Beyond censure are a formal reprimand by the lodge master, exclusion from a meeting, definite or indefinite suspension, and expulsion, which Mackey compares to medically necessary amputation.

Belong to a lodge

Freemasonry is not a solitary pursuit, and individual Masons are generally expected to belong to a particular lodge. Even though Masons generally have the right to visit other lodges as often as they wish, the requirement to have a home jurisdiction still exists, at least in part because dues must be paid somewhere to keep the whole show running. Masons are usually but not automatically installed as members of the lodge where they undergo initiation, but after initiation may petition any lodge they like for membership. Resignation from a lodge, called a demit, is generally freely given if the applicant is up-to-date on dues and not facing any charges within the Masonic system. They may receive a certificate of good standing to present to another lodge if transferring membership.

Unaffiliated Masons remain Masons unless they have been expelled for misconduct, but they lose certain rights while not attached to a particular lodge. They may only visit a given lodge once (to see if they wish to join that particular one) and cannot ask for financial help, receive a Masonic burial, or participate in Masonic processions. They remain bound to all the oaths they've sworn as Masons, are still subject to general Masonic discipline, and may still ask a lodge for help if in particularly dire need.