The Messed Up And Tragic Truth About These Christian Saints

Attend any Christian ceremony, and there's an air of solemnity about it. After all, saints are venerated as figures above the rest of the faithful, and stories are told of their piety and sacrifice. But what's the truth behind the stories? Sometimes, it's gory, bloody, and controversial. It's a strange world, where history and religion intersect, and sometimes, it can get very messy. Very, very messy.

It's easy to forget that many of these saints were real, flesh and blood people. Some have been elevated into an almost mythological standing — here's looking at you, St. Nicholas and St. Patrick — but once, they were just like anyone else, only they stood up for their convictions, and many paid the ultimate price. They had parents and families, people they cared about, and they faced very real dangers when it came to standing up for the faith they believed in. And sometimes, they were the dangers. From horrific martyrdoms to bizarre lifestyle choices, here's the messed up and tragic truth about these Christian saints.

St. Bartholomew, the flayed one

Saint Bartholomew is a great example of how it's almost impossible to find the truth about some of Christianity's biggest saints (including, in some cases, whether or not they even lived). But there are some true tales about Bartholomew that make him worth talking about.

According to Lapham's Quarterly, Bartholomew is credited with traveling to India to spread the word, which is entirely possible. He's also said to have gone toe-to-toe with Death's six serpent sons and to have taken communion with a leopard, a talking goat, and a werewolf, and well, that's less possible.

Bartholomew was martyred in the year 68, when he was skinned alive. That's why he's often depicted in art as holding part or all of his own flayed skin, and that brings the tale to truth. One of the most famous depictions of him is in the Sistine Chapel. He's the one in the Last Judgement, holding his own skin while he looks up at Jesus. His face is hanging off the skin, and the face is a self-portrait by Michelangelo that sums up how he felt about working on the ceiling. Other depictions are equally gruesome. Charles Dickens couldn't even bring himself to look at the work by Nicolo Circignani, it was so bad. Because Christianity isn't without a (dark) sense of humor, he's the patron saint of butchers, tanners, and leather workers.

Junipero Serra was a messed up missionary

First, let's give a quick summary (via The Guardian) of the popular tale. Junipero Serra was a Franciscan monk who left home, headed to the New World, and brought Christianity to California. The heathens he found were captivated by this cheery holy man, and they were converted. That's why Pope Francis officially canonized him in 2015 (via CNN).

But to say there's a huge problem with that is an understatement, as 50 Native American tribes condemned the canonization. Why? Well, they said that missions like Serra's ended up killing around 90 percent of the people they said they were trying to save ... when those people were doing perfectly fine on their own. But Rome, they claimed, wasn't interested in hearing their concerns.

And those concerns were big one. Serra — and other missionaries like him — were known for spreading disease throughout native populations, conscripting them into forced labor, and once the natives entered the missions, they weren't allowed to leave. Rebellions were brutally dealt with, and when Pope Francis said that yes, he was apologizing for Serra's actions, it didn't really make anyone feel better when he was still canonized. At the end of the day, the Vatican's viewpoint was summed up like this: He did more good than bad, and hey, no one's perfect, amirite?

St. Philip Howard's tragic story

It was hard to be a Catholic in 16th-century England, particularly after the 1570 act that made it treasonous. Just two years later, Thomas Howard, the fourth duke of Norfolk, was beheaded for his role in a plot to put Mary, Queen of Scots on the English throne. Norfolk's execution came 25 years after his father was also executed for treason, and before that? Thomas Howard, third duke of Norfolk, only escaped execution because Henry VIII died before he signed the paperwork.

That's the family Philip Howard was born into, and they were still being watched by Elizabeth's spies and informants by the time he came of age. In 1581, he saw something important: the execution of the Jesuit Father Edmund Campion. He was hanged, drawn, and quartered for his beliefs, and he inspired Howard to convert to Catholicism.

In addition to providing shelter to Catholic priests, Howard did it all while still at Elizabeth's court. He decided to flee England and join other Catholic exiles, but Howard was captured when he reached the port. He was imprisoned in the Tower of London and sentenced to death after being found guilty of praying for a win for the Spanish Armada. He was given the chance to leave and rejoin his wife and newborn son, but he refused to recant his Catholicism. He died of dysentery in 1595 and was canonized in 1970 (via the National Catholic Register).

St. Simeon Stylites and St. Martha were an ultra-monastic family

The man who would become known as St. Simeon Stylites was born in 390 in what's now Syria. The Orthodox Church in America says that he was so devout and dedicated to living an austere life that he was annoying the heck out of the other monks, and he was told to learn a little moderation or leave ... so he left.

What's an extreme monk to do? He lived in a well for a bit, but eventually, he moved to a cave where he did things like not eat for 40 days, spend 20 days standing and praying, then 20 days sitting and praying. Not surprisingly, word got out.

So many people started to come visit him that he decided he needed to get even farther away. He built a six-foot tall pillar, put a little platform at the top, and stayed there. He clearly didn't grasp how people would react because even more people wanted to see him. He kept adding to his pillar until it was about 80 feet tall (making him one of many so-called stylites, or pillar-dwellers), and he had a strict "no girls allowed" policy. Unfortunately, that also included his mother, who'd been looking for him this whole time.

He refused to see her when she finally did find him, so she sat at the base of his pillar, waited, and died there. Simon later died at the top of his pillar, and it became a pilgrimage site.

Teresa of Avila might've suffered from a tragic disorder

At a glance, St. Teresa of Avila seems like a pretty standard sort of saint. According to Aleteia, she was born in 1515 and was still young when she became so enamored with the tales of saints who'd come before her that she convinced her younger brother to join her on an adventure to the Middle East. Why? She wanted to meet some Muslims and get martyred so she could meet God.

Her family stopped them before that could happen, and she went on to become a major advocate for literacy and reading. And remember, this was a time when women were encouraged to be subservient to men, even within the church. But here's the problematic part. She was also known to use olive branches to force herself to vomit, so she could absorb the communion host completely and fully. According to an article from the University of Siena, it's entirely possible she was suffering from an eating disorder.

Teresa isn't the only female saint to be connected with regular purging, either. The Guardian took a closer look at the lives of female saints and found that starvation was a common theme. And not just starvation, but a tendency to starve, purge, and liken their starvation and wasting away to Christ's suffering on the cross. Historians have even given it a name — holy anorexia — and is it really something that should be lauded?

St. Lidwina had a messed up condition

St. Lidwina is the patron saint of ice skating, and that sounds sweet ... until you know the reason why, and suddenly, it's not so sweet.

Lidwina was born in the Netherlands in 1380, and she was just 15 years old when she fell while ice skating. She broke a rib that wouldn't heal, and when gangrene set in, she was confined to her bed for what would be the rest of her life. And don't worry, it gets worse.

She took that time to focus on her religion, and she began having visions. She was rumored to eat only the Host and to be able to heal those who came to her, says Aleteia, but there's more to it. According to the National Catholic Reporter, Lidwina's injury and subsequent illness was anything but magical. Official town records from the time report that "she shed skin, bones, and even portions of her intestines, which her parents kept in a vase; and these gave off a sweet odor until Lidwina ... insisted her mother bury them."

Strangely, there are a few other stories about Lidwina before her ice skating incident. One tells of an instance where she slipped and fell on her way into church, and to many, that suggests there was something else going on with her. Many suggest hers is the first case of multiple sclerosis to be documented, while others think she suffered from a neurological disease.

St. Colmcille was a Christian who prayed for a massacre

St. Patrick might be the most famous, but Ireland actually has two other patron saints: St. Brigid and St. Colmcille. The latter lived in the 6th century, and he ultimately became an abbot and a missionary who founded one of the most famous monasteries in Scotland — Iona Abbey — but there was some questionable stuff in between.

Colmcille (aka St. Columba) had his education cut short when plague broke out in the monastery where he was studying, according to Donegal Diaspora. Then after founding a monastery that would grow into the city of Derry, he got into an argument over a book.

Remember, this was well before the printing press was invented, and copying a book meant doing it by hand. He'd copied the Book of Psalms, and St. Finnian claimed both the original and Colmcille's copy. "Monk" doesn't mean "pushover," and Colmcille appealed to the high king. The high king sided with Finnian, and that just added fuel to the fire. Colmcille already had a beef with the king — he'd murdered Curnan, the prince of Connaught, while Curnan was under Colmcille's protection.

So Colmcille turned to his kinsmen and asked them to see justice done. They fought as Colmcille prayed, and at the end of the day, they'd lost one man and the high king's army was entirely and completely dead. Colmcille was overcome with guilt, and he headed into exile in Scotland, where he kept his promise to win souls for Christ.

St. Jean de Brebeuf died a glorious, horrible martyrdom

St. Jean de Brebeuf is most closely associated with Canada, but he was born in France and traveled to Quebec as a missionary to the Huron in 1625. He had something going for him that others didn't — an innate gift for languages that allowed him to communicate very well and very quickly. According to America magazine, he swore that in order to get to know the Huron, he would work, sleep, and eat alongside them, and he would also observe their customs. And he did, even writing extensively on them before being asked to return to France.

He was back in Canada by 1635, though, and was greeted by the Hurons he'd befriended. But trouble started when it became clear that de Brebeuf's missionary friends had brought something else: smallpox. Suddenly, the Hurons who'd been baptized were dying, and the native peoples were less than thrilled about their European visitors.

Rumors later started circulating that he'd befriended the Iroquois, but in 1639, it became painfully clear that wasn't the case. De Brebeuf was taken prisoner by the Iroquois and executed. He was set on fire and had his nose and lips cut off. A hot iron was forced down his throat, and then he was baptized with boiling water. He was scalped and skinned alive, then killed with a hatchet.

Was Padre Pio a saint or fraud?

Padre Pio became a saint in 2002, almost 100 years after stigmata first appeared on his hands. He was born in Campania in 1887, and as a novice monk, he began experiencing some weird things. Some called them illnesses, while others, says The Irish Times, looked at it more as religious ecstasy. After being ordained, he returned to Italy.

His stigmata appeared in 1918, and those who knew him claimed he had the gift of healing, prophecy, bi-location, and that they had seen him perform numerous miracles. Unlikely? That's actually what the church said at the time. His local bishop believed he was less about God and more about the financial gain, and he was investigated by the church. At one point, he was banned from saying mass, hearing confession, blessing the faithful, and answering letters. He wasn't allowed to show his stigmata, either, and had to wear gloves.

Those bans were lifted in the 1930s, and between then and his death in 1968, he had just as many critics as believers. In 2007, a book by historian Sergio Luzzatto claimed to have evidence that he faked his stigmata by using carbolic acid to burn his feet, hands, and sides. According to The Independent, Vatican documents suggest that their own doctors had come to the conclusion the wounds were self-inflicted, but they also seemed not to heal when they were sealed and taped. So was the man a saint or fraud?

Benedict Daswa was a Christian who doubted witchcraft

As of 2019, Benedict Daswa isn't a saint — not yet, anyway. But according to The Telegraph, he's not only on his way to sainthood, but to being South Africa's first saint. He was beatified in 2015 — one of the steps on the road to sainthood — and he's a bit unique in that his family is still around to not only see it, but to live side-by-side with those who murdered him.

Daswa's eight children and his 91-year-old mother were there when Pope Francis declared him "blessed," says the Catholic News Agency, and Daswa's story is a heartbreaking one. He was born Jewish and converted at 17, going on to become a primary school principal and teacher. Most importantly, he took a stand against beliefs in witchcraft. In 1990, his village suffered from a series of terrible weather phenomenon — first drought, then rains and floods. Daswa not only refused to pay a "sorcerer" who promised to wizard away the bad weather, but he refused to join in a very literal witch hunt, where villagers were determined to find the one causing the bad weather and put a stop to it. There were confrontations, and Daswa was on his way home a few nights later when he was ambushed and brutally murdered for his denouncement of witchcraft.

Giuseppe Puglisi was matyred by the Mafia

Father Giuseppi Puglisi isn't a saint just yet, but he was beatified in 2013, so he's on his way. He was murdered in 1993, and according to the National Catholic Register, that makes him the first person to be martyred by the Mafia.

At the time of his death, he'd spent decades serving the faithful in towns across Sicily, including Godrano, which was in the middle of a blood feud when he'd arrived in the 1970s. Puglisi, his peers say, won over the kids and the families first, and by the time he left the village, the feud was over, and peace had been restored.

Then, in 1990, he was assigned to become parish priest in an area of Palermo run by the Gravianos Mafia. While he wasn't a traditional anti-Mafia priest (there were no rallies or public condemnation of Mafia activities coming from his parish), it wasn't long before they realized his ways were just as dangerous. He started by appealing to the children, encouraging them to focus on their studies and their education, which ultimately meant turning away from a life of crime. He was warned repeatedly, but he kept up his work. Until, that is, Mafia hitmen showed up on his doorstep on September 15, 1993. His last words? "I was waiting for you."

His murder spurred the Church on to make a public condemnation of the Mafia, something they'd hesitated in doing before.

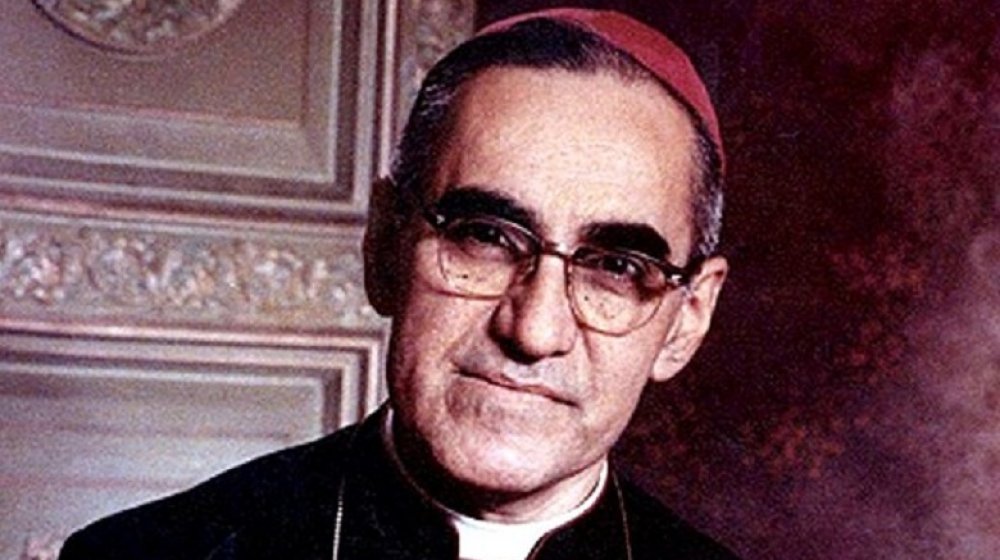

St. Oscar Romero was murdered for giving the voiceless a voice

Oscar Romero was canonized in 2018, almost 40 years after he was assassinated. He was killed just as he finished a sermon at the chapel in San Salvador's Divine Providence Hospital, hit by a single bullet from a single assassin. Why? Because he wasn't about to let injustices slip away unnoticed.

According to The Irish Times, he started out his career as a bit of a cynic, until working in rural El Salvador made him a witness to the hardships suffered by the people there — hardships delivered mostly by official security forces on patrol. In 1977, a close friend was murdered, and the government refused to investigate.

Romero began to preach — eventually on the global stage — about the social injustices, poverty, and murders happening in his country. He condemned the US for aiding El Salvador's government, spoke publicly against the torture and murders of priests and nuns, and as he built up a larger and larger following on his Catholic radio program, he began reading the names of those who were killed or who'd simply disappeared. Death threats became the norm for him, and the assassin came the day after he'd condemned the soldiers of El Salvador for blindly carrying out orders, even though they had to know those orders were against all Christian beliefs. The gunman was never brought to justice.