What It Was Like The Day Hitler Died

It will likely come as little surprise to learn that, for many, the day Hitler died was a pretty grim one. To start, the situation in Berlin, where Nazi leader Adolf Hitler and a small group of supporters were hiding in an underground bunker, was dire. The city had already been encircled by Soviet soldiers and their Red Army was making headway into the heart of the capital. Their assault, known as the Battle of Berlin, ground on from April 20 to May 2, 1945, and left an already crumbling Berlin in even greater disrepair. Just 10 days after the battle had commenced, Hitler had decided that he was by no means ready to face justice and died by suicide on April 30. Just over a week later, on May 8, the Allies were celebrating Victory in Europe Day and Germany was facing the division of its territory amongst the Allies. Japan, the last remaining member of the Axis powers, didn't surrender until August 1945.

Even as Hitler was finally defeated, that didn't mean the war or its repercussions suddenly ceased to exist. The experience of living through April 30, 1945, was one that many people would surely remember for the rest of their lives.

Soviet forces were advancing on Berlin

By April 30, 1945, the Soviet Red Army had already put Berlin in a chokehold. The Battle of Berlin – one of the deadliest engagements of the war — actually began about 10 days earlier and didn't end until April 2. Soviet soldiers were ready for revenge, as many recalled German offensives such as the brutal Battle of Stalingrad, a more than six-month siege that had ended in February 1943. At Stalingrad, official Russian estimates claim more than 1 million military deaths, with a further 40,000 civilian deaths. The siege of Leningrad, which ended in January 1944 after almost 900 agonizing days, is said to have claimed the lives of more than 800,000 civilians, many of whom died of starvation.

When it came time for the Red Army to descend upon Berlin, it did so with a fury. Besides gunfire and shelling, grim accounts of widespread sexual assault were later reported by German civilians. The outlook was bleak for the defenders, some of whom were only teenagers armed with the bare minimum of weapons. As former German soldier Heinz Reinhart told American Experience of his time as one of these teenaged defenders, "We thought we had to fulfill our duty at the position where we had been stationed." But ultimately, Reinhart said "that the whole story simply had no prospects for success anymore. Be we were, as I said, jaded and callous and accepted everything as it came."

Things were pretty grim in the bunker

With the Red Army closing in on Berlin, Hitler was already ensconced in a reinforced bunker near his chancellery headquarters. In fact, he had gone down into the 18-room bunker on January 16. By April 22, he got word that a key attack had failed to materialize. Hitler apparently broke down, loudly proclaiming that Nazi Germany was doomed. The reassurances of officials around him in the bunker did little to assuage Hitler, who had admitted defeat and was now clearly planning to die by suicide rather than come under Soviet control.

Though his motivations aren't fully clear, it's almost certain that the news of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini's brutal death had something to do with it. Killed by a partisan mob, Mussolini's remains (along with those of mistress Clara Petacci and 14 others) were dumped in a public square in Milan and greatly abused by a crowd. Hitler reportedly claimed he would not allow such a thing to happen to himself, ordering that his body be cremated.

Hitler then decided that he would finally marry his longtime partner, Eva Braun, who seemed briefly excited, but the final days of Hitler were hardly glowing as Russian munitions fell in the vicinity.

The bunker became the site of multiple deaths

After what appeared to be a downbeat wedding — marked by a pointless bureaucratic snafu in which lawyer Walter Wagner (who had never met Hitler before) forgot the right paperwork — Hitler completed his political testament and private will, dictating the contents of both to secretary Traudl Junge. She typed it up while a wedding reception with liverwurst sandwiches and Champagne took place.

According to Junge's account, "Until the Final Hour," by April 30, Braun and Hitler made their final goodbyes. Braun urged Junge to try and escape Berlin (having already gifted the younger woman her own fur coat; Hitler gave Junge a cyanide capsule). According to valet Heinz Linge's memoir, "With Hitler to the End," Hitler stated: "Linge, I am going to shoot myself now" and also told him to do his best to leave the city. Officials and aides in the bunker shortly found the couple dead on a sofa in Hitler's room.

The next day, more death followed. Propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, along with his wife Magda and their six children, had also been staying in the bunker. After Hitler's death, Goebbels was briefly German chancellor, though he and Magda poisoned their children the next day and also died by suicide.

Multiple concentration camps had already been liberated

The first liberation of a large concentration camp came in July 1944, when Soviet troops moving through Lublin, Poland, uncovered the half-dismantled Majdanek. Some prisoners remained, but many had been moved to camps like Auschwitz (which would be liberated by the Red Army in January 1945). Though Nazis had attempted to do away with much of the evidence at Majdanek, enough remained to speak to the atrocities committed there, from the accounts of remaining prisoners to the mountains of personal items (and 14,000 pounds of human hair).

As troops moved further into Germany, they encountered more concentration camps, human remains, and starving, disease-afflicted survivors. As U.S. soldier Andrew "Tim" Kiniry told the National World War II Museum in an oral history, his experience liberating Buchenwald was gut-wrenching. "I don't think they told us what we were getting into," he recalled, noting that local Germans must have known something was wrong by the stench of the camp alone. By April 29, Dachau had also been liberated by U.S. troops, who faced similar horrors — including an appalling "death train" containing thousands of abandoned human remains — and joined the growing group of people who would learn the true extent of Nazi atrocities. At Dachau, American soldiers summarily executed German soldiers and other German prisoners that had been found nearby and inside.

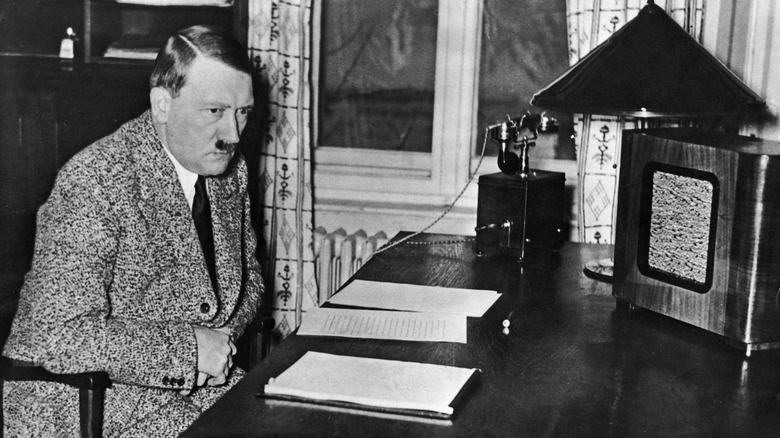

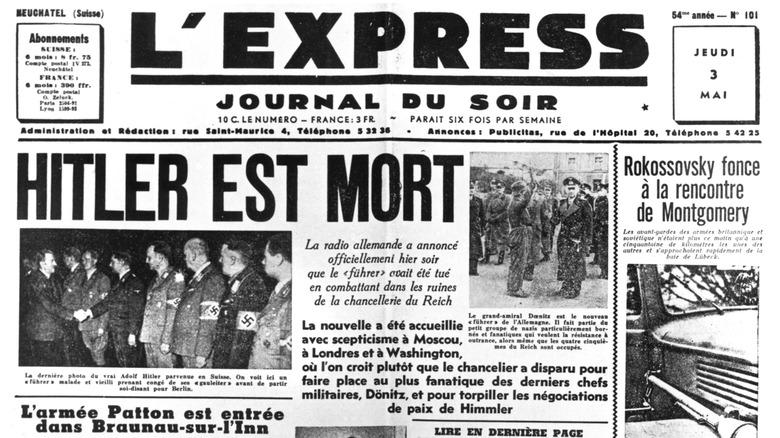

News of Hitler's death was confusing

Beyond those who handled Hitler's remains on April 30, the circumstances of his death weren't quite so clear that day ... or for a long while after. In the confusing aftermath, many began to wonder and spin tales of a führer who had escaped and started a new life elsewhere. A May 1945 report in Time magazine acknowledged that Hitler was almost certainly dead, but then referenced conflicting causes of death and even the notion that Hitler was alive but held by the head of the Gestapo, Heinrich Himmler. Even the BBC and its listeners weren't totally sure what was going on, as many wondered if Hitler had somehow died in combat.

Why the confusion? For one, the Soviets got involved. It was long rumored that Red Army soldiers had salvaged some of Hitler's remains. However, it wasn't until 2018 that this was more or less confirmed, when skull and jaw fragments held by Russia matched up with Hitler's X-ray and dental records. The skull portion displays what appears to be a close-range gunshot wound, consistent with firsthand accounts from within the bunker.

Others held onto the survival notion, either because they weren't ready to give up on the idea of Nazi Germany or because they wanted Hitler to be publicly brought to justice. But, even before the physical evidence came to light, the numerous first-hand reports and official investigations made it clear that Hitler had died on April 30, 1945.

Aides hastily attempted to dispose of Hitler's remains

Hitler's death marked a major moment in world history and the course of World War II in particular. But for those still inside the chancellery bunker, there remained a practical, if seriously unpleasant question: what to do with the bodies? Hitler himself had already given some indication as to what should happen next, having directed aides to fully destroy his remains. Therefore, SS officers wrapped Hitler's now-disfigured corpse in a blanket and hauled it up four flights of stairs into an open area just outside the bunker. Braun's remains were also carried up in a similar fashion. Heinz Linge wrote that the remains were placed in a small ditch and, because Soviet shelling was too intense to allow for much standing around, some papers were lit and then tossed onto the gas-soaked bodies.

One of the few outside witnesses to this event, Erich Mansfeld, was an on-duty guard situated in a nearby observation tower who, upon hearing a commotion of sorts below him, went down to investigate. He reported seeing a concealed corpse wearing black pants and the unwrapped and identifiable remains of Braun. After being yelled at by bunker inhabitants, he returned to the tower. Another guard, Hermann Karnau, managed to witness the moment both bodies, doused in gas, were set on fire (an event also witnessed by Mansfeld from the tower).

Some German scientists were preparing to flee

Elsewhere in the crumbling German state, many scientists understood that, because they held information about nuclear weapons research, they were key targets. By 1943, a secret Allied unit known as the Alsos Mission (or Lightning A), led by U.S. Colonel Boris T. Pash, had begun investigating the Nazi atomic program. By April 22, 1945, Pash's team had made its way ahead of Allied forces and into Heidelberg and its environs. There, they uncovered a nuclear lab and quickly set about destroying its reactor. They also recovered files fleeing scientists had submerged in a cesspool, along with uranium and other radioactive materials buried nearby.

Just two days after Hitler's death, Lightning A managed to detain a group of German scientists, including top physicist (and 1932 Nobel Prize winner) Werner Karl Heisenberg. Though Heisenberg spent only a brief time held by the Allies, others made a far more lasting move. Wernher von Braun, a top rocket scientist, emerged from hiding in Austria to surrender. Thanks to Operation Paperclip, a short-lived U.S. venture that allowed key Nazi scientists to emigrate to the U.S., von Braun became an employee of the U.S. Army and later NASA, where he led the team developing the Saturn V rocket that carried Apollo 11 astronauts to the moon.

Many cities were in ruins

Troops moving into Berlin on April 30 would have encountered a city that, at times, seemed to be more of a smoldering wreck than a place where people once lived their lives. Starting April 23, Berlin was completely surrounded and bombarded by artillery that blasted buildings and took many lives. Encounters between advancing Allies and defending German troops, as well as civilians, produced even further damage. Even worse, perhaps, was the state of Dresden.

By February 1945, Dresden had been almost entirely razed by a bombing campaign meant to instill shock and despair. Most estimates claim somewhere between 25,000 to 35,000 civilians killed in the firebombing campaigns against Dresden alone, though others argue that the number could have been far higher due to an influx of refugees.

Over in Japan, Tokyo was subject to a brutal firebombing campaign that some have since deemed the worst act of war in history (and that includes the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki). On the night of March 9, 1945, around 100,000 people were killed in the firestorm set off by Allied bombers above Tokyo. A further million were left without homes, speaking to the widespread devastation that left much of Japan's capital in ashes. Even if they weren't directly harmed by enemy troops or bombs, people worldwide experienced hardships due to supply chain disruptions, wartime rationing, and the movement of refugees. Even after the war, most nations grappled with the economic and social aftershocks of the conflict.

The Cold War had already begun

Even as Hitler was still alive, the Cold War had begun to germinate. Tensions amongst the Allies became more obvious at the February 1945 Yalta Conference, where British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin met to plan the shape of the postwar world. Though WWII had not officially concluded, the writing was on the wall. Hitler had already fled to his bunker, the war in the Pacific had begun to sour for the Japanese as it lost more and more territory, and fascist Italy was beginning to crumble. For the major commanders of what was shaping up to be the victorious side, it was time to make a plan for the aftermath.

Stalin's Red Army had a commanding presence in Europe that eclipsed that of Britain or the U.S. All three had seemingly different goals, and neither FDR nor Churchill was especially keen on letting the Soviet Union grow into an even more dominant power. But who else was there to rely on but each other? Ultimately, they hammered out a deal that included a split Germany controlled in a hodgepodge of different zones, as well as the okay for the United Nations to go ahead. FDR also got Stalin to agree to invade Japan if the war came to such a point, but Churchill never got an assurance of an independent Poland.

The US was still reeling from the death of FDR

When FDR appeared at the Yalta Conference, it was uncomfortably clear to all in attendance that the president was unwell. Just two months later, Roosevelt was dead. Though he was 63 years old and had just been elected to a fourth term, Roosevelt was suffering from a variety of maladies like shockingly high blood pressure and heart failure, not to mention the stress of the presidency. Perhaps if everyone had known the true extent of the president's health problems, his sudden death from a stroke on April 12, 1945, would have been less of a surprise.

FDR had been visiting Warm Springs, Georgia, and was sitting for a portrait when a stroke hit him. That left Harry Truman, FDR's oft-ignored vice president, to take the reins. Rushing to the White House, he was greeted by Eleanor Roosevelt, who told Truman of her husband's death. When he asked how he could help, Eleanor reportedly replied: "Is there anything we can do for you? For you are the one in trouble now" (via The New York Times).

The public heard of the president's death within two hours, and at about the same time that Truman was sworn in as president. While even regular citizens had noticed a turn in Roosevelt's appearance and had begun to speculate on his health, as well as what the U.S. might do if he suddenly died, when that truly came to pass, it was still a grim surprise.

The United Nations was getting its start

On the day of Hitler's death, the nascent United Nations was already in the midst of one of its earliest meetings. The San Francisco Conference included 46 invited nations that had signed onto the United Nations Declaration, along with four other nations, for a total of 50. Beginning on April 25, delegates (about 850 total) met and approved the organization's charter and the framework for its International Court of Justice, a point that many consider to be the true creation of the U.N. and the start of its history as a working organization.

President Harry S. Truman delivered an address to the conference via wire. After paying tribute to the recently deceased FDR, he said, "By your labors at this Conference, we shall know if suffering humanity is to achieve a just and lasting peace." Truman — and surely everyone who listened to or read the address — was also clearly reflecting on the bloody war that was only then grinding to a close. "The essence of our problem here is to provide sensible machinery for the settlement of disputes among nations. Without this, peace cannot exist," Truman argued. "If we do not want to die together in war, we must learn to live together in peace."

The world was poised to see major technological advancements

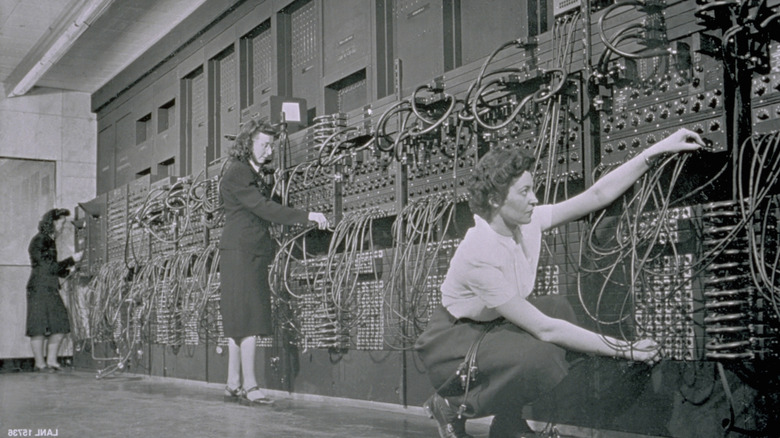

With so much of the world in shambles, to some it may have seemed ridiculously hopeful to think that something helpful would come out of all that suffering. Yet, with the benefit of hindsight, we can see that the war led to major technological advancements that influence us today. Many were already completed or nearly so by the time April 30 came around. Radar technology improved dramatically during the war, thanks in large part to a device known as the cavity magnetron, which produces microwaves and became an important component of modern microwave ovens.

And while computers had gotten their start long before World War II (Ada Lovelace, one of the earliest-ever computer programmers and a clearly ahead-of-her-time scientist, lived in the early 19th century), the war pushed computer science dramatically further. The massive calculating machine known as the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC) had its start as a military device and was finally released to the public in 1946, whereupon it became a major advancement that helped scientists complete about 5,000 calculations per second (modern computers have taken that per-second number into the billions).

Medicine also took huge leaps forward thanks to the demands of war, from U.S. Army-sponsored research into flu vaccines (the first military flu shot was approved in 1945) to the mass production of penicillin to aid wounded soldiers. Likewise, blood plasma became easier to transport and administer thanks to doctors looking for a fast battlefield solution.