The Biggest Contradictions About God In The Bible

For the faithful of multiple world religions, it may seem as if the God of the Bible is a solid, unchanging, and immutable force. That's how it may be taught, but a look at one source can sometimes introduce considerable doubt. That source? The Bible.

Maybe it's not all that surprising when you consider that all the books of the Bible, from the opening Genesis to the final Book of Revelation, were written over the course of about 1,500 years. The Hebrew Bible — essentially, what many now call the Old Testament — was done by around 100 B.C., while the New Testament was complete by the second century. Scholars now broadly agree that the Bible was written by many different people, though many of those writers are unnamed, and somewhat smaller-grained arguments about the number and name of all those authors are sure to start serious debate in churches and conferences everywhere. The point is, with so many hands in the creation of the Bible, no wonder that it contains contradictions about the very nature of God himself.

These discrepancies include competing verses about God's motivations, ultimate plans, positions on key issues like human sacrifice, and whether or not you really ought to be circumcised. Even the basic timeline of how God created all of existence — and when and how the very first humans came to be — gets muddled very early on.

Did God create existence once or twice?

The first chapter of Genesis starts, naturally enough, with God creating everything. Then, the second chapter ... retells the creation story? The whole thing starts all over again, but with some oddly changed details. Genesis 1:27, for instance, only vaguely mentions the creation of male and female humans after the animals, telling them (without specification to gender) that humans are to have dominion over the earth, its plants, and creatures. But then Genesis 2 comes along with a more complicated tale that has the male human, Adam, created first and the female Eve made from his own body after God determines Adam is lonely. It's only here that a Garden of Eden is mentioned.

Even within a single chapter, things don't necessarily line up. God creates light on the first day in Genesis 1:2-3, but the sun, moon, and stars don't show up until the fourth day, per Genesis 1:14-19. From a scholarly perspective, it could just be that Genesis is a mash-up of accounts written by different people and perhaps not all that carefully compiled into a single book.

Those arguing from a religious perspective also more or less state that it's okay if there are some differences, so long as the basic themes line up. However, it's hardly satisfying from the point of view of a biblical literalist, and many still argue that it carries some uncomfortable questions about what God was doing in the beginning of the Bible.

It's not entirely clear if God is the only divinity or not

Is God the only divine being in the Bible? Many faithful Christians will likely say that, yes, of course there's only one God. Deuteronomy 6:4 plainly states that "the Lord our God is one Lord," while Isaiah 43:10 likewise quotes God as saying "before me there was no God formed, neither shall there be after me." Over in the New Testament, the Gospels say the same, from Mark 12:29 having Jesus effectively quoting Deuteronomy to Paul's statement in 1 Corinthians 8:6 that "to us there is but one God, the Father, of whom are all thing, and we in him."

But others will point out some additional verses that, viewed in a certain light, introduce doubt. In a couple of places in Genesis — Genesis 1:26 and 3:22, to be exact — God is recorded as referring to "us" and not "me." And, yes, that's borne out in the original Hebrew as much as the English translations and which elsewhere in the Hebrew scriptures are used to refer to groups of people.

Some have argued this is a case of "majestic plural," meant to get at the awe-inspiring, all-encompassing nature of God. Others point out other verses that specifically say other gods are false or might be demons instead (like in Deuteronomy 32:17). Still, uncertainty — like the mysterious reference to potentially quasi-divine "sons of God" in Genesis 6 — remains.

Can you see God face-to-face or not?

The idea of meeting God in person and seeing what he really looks like may conjure up images of the bad guys from "Indiana Jones" getting their faces melted off, but what do the scriptures actually say about the possibility of an in-person meeting with God?

John 1:18 has it that no one's seen God, but flip back to Genesis 32:30 and Jacob says, "I have seen God face to face, and my life is preserved." And that's after he not only directly encountered the divine, but engaged in a marathon wrestling match with it — either in the form of an angel or maybe God himself. Exodus 33:11 says that Moses spoke to God "face to face, as a man speaketh unto his friend," then in Exodus 33:20, God tells Moses, "Thou canst not see my face: for there shall no man see me, and live." Moses instead sees just a bit of God through a void in a rock. In the Gospels, Jesus likewise says it's impossible to see God's face in John 1:18.

It could be that the human imagination is simply not up to the task and that all of these instances of ancient people getting a glimpse of God's face are metaphorical. Others suggest that God has a way of scaling back his divine yet deadly glory, but the Bible itself doesn't produce such easy answers on its own.

The Biblical God is inconsistent about human sacrifice

You may think that human sacrifice is forbidden by God, but, according to some parts of the Bible, that's not necessarily true. In Genesis 22, God commands the ancient prophet Abraham to sacrifice his only legitimate son, Isaac. With little word as to why he was asked to sacrifice Isaac, Abraham restrains the boy on a sacrificial altar but, before the knife can fall, an angel stops him and points out a ram caught in a nearby bush that will act as a proxy.

It hardly stops there. In Judges 11:29-40, Jephthah promises that he will sacrifice whoever first greets him upon his return, as long as he prevails in battle. In a tragic twist, Jephthah's own daughter comes out to see him and is sacrificed. In Numbers 31, "the Lord's tribute" includes 32 captives (after male children and non-virginal women are killed, and the remaining women are to be kept for the Israelites, per Moses' command). And in 2 Samuel 21, King David resolves a famine (due to the sins of his predecessor Saul) by sacrificing some of Saul's sons and grandsons. Even Jesus is obliquely or directly referred to as a human sacrifice meant to atone for the sins of the whole species, as when 1 Corinthians 5:7 compares Jesus to a sacrificial Passover lamb.

But Leviticus 18:21 presents a stark contrast when it forbids child sacrifice to the pagan god Molech, and a common interpretation of the Abraham and Isaac story is that it is a symbolic repudiation of the practice of sacrificing people.

Different verses have different takes on God's jealousy

Does God get jealous? Depends on who you ask and which book of the Bible you turn to. Exodus 20:5 says that God indeed gets jealous when he directly states "for I the Lord thy God am a jealous God." Seems pretty darn clear, at least until you get to Proverbs 6:34, which claims that "jealousy is the rag of a man." Certainly Paul writes in Galatians 5:20 that hatred and wrath — of which jealousy is surely a part — is a sin.

So, is God exempt from this sort of sin? Some believe so, or at least they argue that jealousy in a divine sense is very different from the petty concerns of humanity and how we mishandle difficult emotions. God's jealousy may be more properly interpreted as a kind of divine indignation when humans don't worship him and instead pay too much attention to something else, be it another god or some more vague concept like wealth or power. Human jealousy can also encompass wanting something that isn't yours, such as making wolf eyes at another person's partner. But this isn't clearly laid out in the Bible directly, making it potentially difficult to discern just when divine jealousy is warranted.

Generational curses may or may not be an aspect of divine retribution

Should you have to pay for the wrongdoing of your parents? Many people today would surely say not, at least in concept. But what about the God of the Bible? Again, a deep reading of the scriptures presents dramatically different takes on the matter. Many verses — like Exodus 20:5, Exodus 34:7, Numbers 14:18, and Deuteronomy 5:9 — reference divine retribution echoing down the years, even to the third and fourth generation after the original offender. In 2 Samuel 21, David sacrifices some of the sons and grandsons of former king Saul to effectively atone for the sins of the old ruler (more specifically, David hands them over to the Gibeonites attacked by Saul, and the Gibeonites proceed to hang the men).

But then Ezekiel 18:20 rather strongly states that "The son shall not bear the iniquity of the father, neither shall the father bear the iniquity of the son." Neither was Jesus a fan of the concept, though it was certainly around in his time — when Jesus encounters a blind man in John 9, he wonders: "who did sin, this man, or his parents?" He then answers himself, saying, "Neither hath this man sinned, nor his parents: but that the works of God should be made manifest in him."

One interpretation of all this holds that perhaps generational curses are more reflective of divine or natural consequences for bad behavior, which can certainly be learned and passed down to the next generation. Another point of view notes that Jesus can be viewed as an opportunity to break this inheritance, though it remains debatable whether it's a direct consequence of God's displeasure or one's own fault.

God may or may not change his mind

God is often depicted as immutable, as an ageless and unchanging force for whom regret is a nonsensical concept. After all, Numbers 23:19 says that "God is not a man, that he should lie; neither the son of man, that he should repent." But consider 1 Samuel 15:10-11, in which it certainly sounds like God regrets putting Saul on the throne. "It repenteth me that I have set up Saul to be king," he admits. Sure, it's because God has seen Saul going against God's commandments — but wouldn't he have known about all that already?

Other verses might start to introduce the unnerving feeling that God can change his mind and perhaps even make mistakes. In Jeremiah 18:8, God states, "If that nation, against whom I have pronounced, turn from their evil, I will repent of the evil that I thought to do unto them." And back in Exodus 32:14, God seemingly gets heated indeed when he sees the just-escaped-from-Egypt Israelites worshipping a golden calf, but then Moses talks him down and "the Lord repented of the evil which he thought to do unto his people."

It could be that this is another case of humans misinterpreting things and tacking their own perceptions onto a deity that is beyond their full understanding. And perhaps it's not fair to expect God to anticipate every minutiae of human behavior, say some, especially if humanity can be so often unpredictable.

Does God demand circumcision or not?

For early Christians, one of the most difficult prospects of joining the faith was the possibility of circumcision. The physical mark of the covenant between God and his people is mentioned way back in Genesis, where it's first described in Genesis 17. "Every man child among you shall be circumcised," God commands Abraham, starting with 8-day-old male infants. Just about everyone needs this particular bit of flesh removed, including enslaved men ("he that is bought with thy money," as God puts it). So, circumcision is clearly a big deal, and a physical mark that is meant to set apart those who are in with God from those who are not.

But come around to the New Testament, and religious leaders are less keen on the idea. This may have been for practical reasons, since it represented a significant roadblock to letting others join the growing Christian faith and to distinguishing their religion from Judaism. In his letter to the Galatians, Paul wrote that "if ye be circumcised, Christ shall profit you nothing" (Galatian 5:2). In Colossians 2:10-11, Paul similarly writes that a more spiritual form of circumcision is totally fine, and in 1 Corinthians 7:18 he writes that Christians don't have to worry about the practice, saying "Is any called in uncircumcision? Let him not be circumcised."

God may or may not want to tempt people

Is God all that interested in tempting people? Doesn't that seem like, well, more of a Satan thing? Besides the many things people get wrong about the Devil anyway, God's role in temptation is pretty tricky. Some portions of the Bible sure make it seem like God has a role in perhaps pushing people to stray from their righteous paths. In Genesis 22:1, God tempts the original Biblical patriarch, Abraham, to sacrifice his only legitimate son, Isaac (though other translations change this to "test"). King David faces a similar situation, when God "moves" David to take a census of the people of Israel in 2 Samuel 24:1 (curiously, 1 Chronicles 21:1 says that it's actually Satan who pushes David into this misdeed, though also a look at the Hebrew makes it even less clear who was inciting the potentially prideful census).

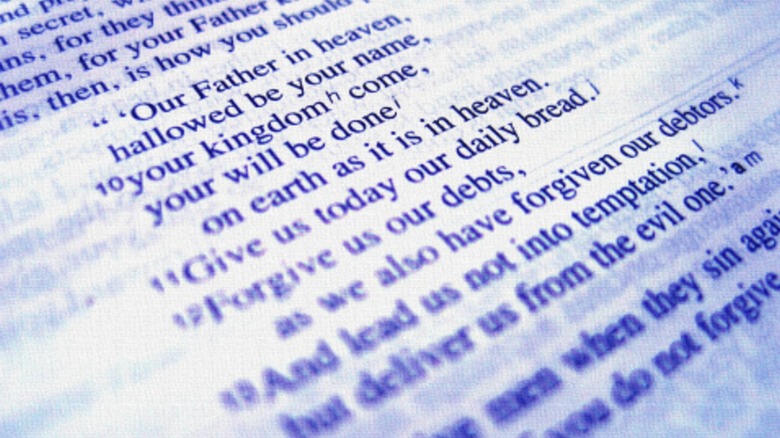

For many raised in Christian traditions, the very familiar Lord's Prayer as recited in Matthew 6:13 includes the line "And lead us not into temptation." Then there's the admittedly grim tale of Job, which includes an early conversation in Job 1:12 between Satan and God where God allows Satan to try and lead Job away from his faith via terrible misfortune (one might interpret this God-approved test as indirect temptation).

Jesus' divinity is unclear

The question of whether or not Jesus was all-divine or all-human has long sparked debate and is one of the things people often get wrong about Jesus. Supposedly, St. Nicholas even struck Arius of Alexandra at the First Council of Nicaea in AD 325, as Arius claimed that Christ was not actually divine (though the story pops up about 1,000 years after Nicholas died). But the Arian controversy was a very real thing and centers on the conflicting information the Bible gives about whether or not Jesus is really, fully linked up to God.

For Bible verses, there's Philippians 2:5-6, another letter (or collection of letters) written by Paul to an early Christian community. There, Paul says that Jesus "being in the form of God, thought it not robbery to be equal with God." In John 10:30, Jesus is recorded as saying, "I and my Father are one"; earlier in John 8:58, he says that "before Abraham was, I am" referencing a way God refers to himself in Exodus 3:14.

However, it's worth noting that, while the Gospels claim to record the words of Jesus, none were written during his lifetime. The Gospel of John — the only one in which Jesus calls himself God — was likely written 60 to 70 years after Jesus' death. It would be odd indeed if Jesus made such major claims and yet three of the four Gospels failed to mention them.

Is God warlike or merciful?

Is God nice or, well, not-so-nice? The evidence in the Bible is, frankly, all over the place. On the side of God being warlike, Exodus 15:3 says that "The Lord is a man of war," while other passages reference God teaching his faithful to fight. Meanwhile, there are multiple disturbing parts of the Bible in which God calls for the deaths of entire people. Looky-loos who peeked into the Ark of the Covenant earned the deaths of some 50,000 people, per 1 Samuel 6:19, and God is repeatedly described in the Old Testament as lacking pity for those who suffered by his hand. In Ezekiel 9:5-6, he instructs some to go through a city and "Slay utterly old and young, both maids, and little children, and women."

But what about the merciful side of things? Later on, Paul wrote in 2 Thessalonians 3:16 that God was "the Lord of peace," much as he would in his letters to the Corinthians. James 5:11 says that "the Lord is very pitiful and of tender mercy," while 1 John 4:16 plainly states that "God is love."

So, in the end, which is it? Maybe both. Some biblical scholars argue that the biblical God can contain both merciful and wrathful sides, though how that's depicted by the multiple authors of the Bible is admittedly inconsistent. Likewise, some Jewish scholars have argued that the sometimes-angry God of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) can be colored by who is doing the perceiving (and who may be the recipient of that wrath).