The Most Insane Acts Of Resistance Throughout History

History is shaped by conflict — it's human nature to oppose each other. We define ourselves by the concept of "us," and those who aren't "us"? That's "them," and most of the time, that's an indicator of some conflicting ideals. The problems start when one of those groups tries to force their ideals on others, and let's be honest — that's most of the time. When it comes to resistance, sometimes it's much more subtle than outright war. It's not always launching a missile or opening fire, sometimes it's much more creative.

And here's the thing about resistance — it always comes at a price. Fighting for what you believe in, fighting to make the world a better place, fighting to get your message across ... it's never easy. Sometimes, resistance means going to extremes, and when people feel they have little or no choice left, those extremes can get pretty insane. It's not always the soldiers that make the biggest difference, sometimes it's the ordinary civilian who steps up and says, "I don't like this, and I'm going to do something about it."

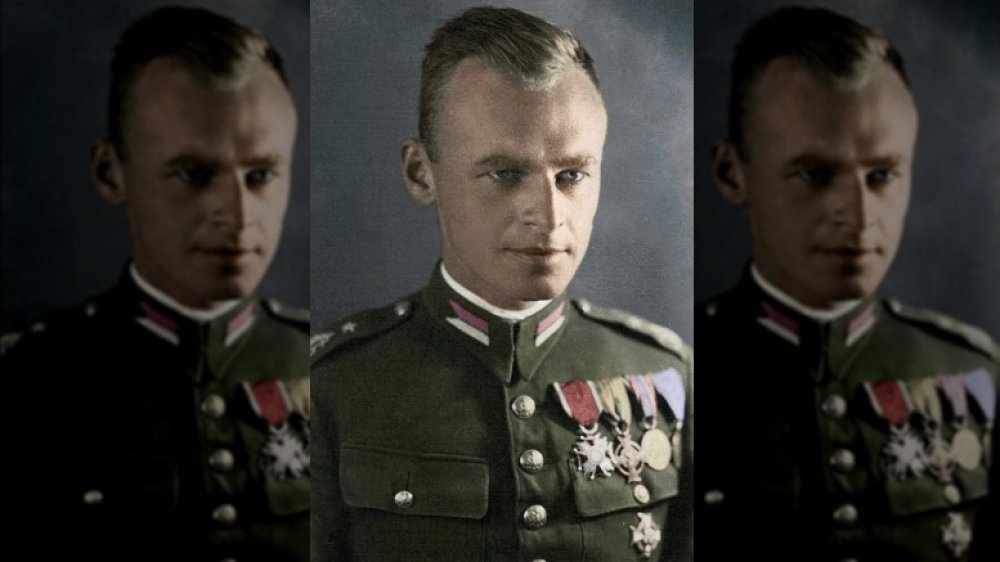

The man who volunteered for Auschwitz

Witold Pilecki was living a pretty normal life on the farm when the Nazis rose to power. He wasn't about to just keep his head down and ignore what was going on around him though, and on September 19, 1940, the Catholic Pilecki was in Warsaw when the soldiers came. He was rounded up with a group of other people and sent to Auschwitz — and he had volunteered to do it.

Author and foreign correspondent Jack Fairweather uncovered his story in 2011, and he told Time it completely changed the way he saw life in concentration camps. Pilecki was at the heart of a cell of resistance fighters — many who were recruited from among the ranks of the prisoners there — who spent their days and months sabotaging camp facilities, smuggling messages and information out to the Allies, and even assassinating SS officers. According to the Jewish Virtual Library, Pilecki had confirmed the Nazi's goal of exterminating the Jews as early as 1941. His group then confirmed the existence of the gas chambers in 1942, and it wasn't until 1943 he realized he needed to get out — help wasn't coming. He escaped, crossed 100 miles of Nazi territory in just a handful of days, and rejoined the Polish Army.

The end of his story isn't a happy one. He was ultimately captured and tortured by the Polish Communist regime and executed in 1948, nearly erased from history before being awarded some of Poland's highest decorations in 2006.

Irom Sharmila's 16-year hunger strike

On November 4, 2000, Irom Sharmila sat down by a pond, and ate some pastries. She wouldn't eat again for 16 years. Sharmila did it to protest India's Armed Forces Special Powers Act, says the Smithsonian. In a nutshell, the law gives the military the freedom to shoot and kill any civilian in any neighborhood that's been designated a "disturbed area." After 10 civilians were killed waiting for a bus, Sharmila decided to go on a hunger strike until the law was repealed.

It wasn't long after she started her hunger strike that she was arrested, for violating a law that made attempting suicide illegal. For the next 16 years, Sharmila lived in a hospital room, under constant surveillance, force-fed through a tube in her nose. She became a symbol of the resistance, at the same time she said (via The Guardian), "I was isolated and idolized, living on a pedestal, without voice, without feeling." Outside, people kept dying and those who killed them got off because of the law she was protesting.

Unfortunately, 16 years into her hunger strike, nothing had changed. She announced the end of her strike and did end it — with a taste of honey — in 2016. Her plans to run for government office failed, but she did marry, move to Bangalore, and said she had no plans to return to the city where she spent more than a decade and a half as a hostage to her own protest.

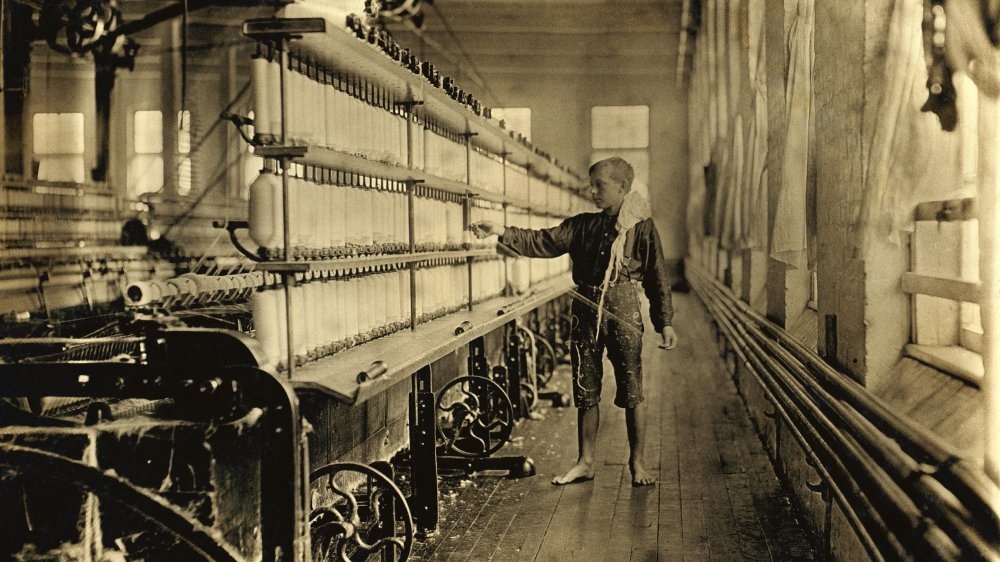

The Luddites take a stand

Call someone a Luddite, and that sends a very direct message. They're old-fashioned, out of touch, and just, well, not very sophisticated. But the term actually comes from something very different, and the original Luddites were a group of skilled, middle-class workers who were protesting the loss of their livelihood. If anything, they were fighting for a world that might have been much better than the one that exists now.

In the early 1800s, the Luddites — weavers and textile artisans — started smashing factory equipment across Britain. They paid for it, too, with many being sent away in exile or even executed for their crimes. What were they resisting? The heavy boot of factory owners. The Luddites were campaigning for things like a minimum wage, a fair share of the profits that came from the goods they made, pensions for workers, and fair working conditions. Since technology was making the process easier and faster, workers were able to make a better product — and more of it. All they wanted was their fair share.

According to Quartz, the end was swift. It became a capital offense to smash factory equipment, and when special gallows were made to hang offenders — including a 16-year-old boy — it discouraged the fight for better working conditions in a world that had been turned upside down by recession, trade barriers, and changing fashion. Sounds familiar, right?

The self-immolation of Buddhist monks

If there's any form of resistance that might be considered the most extreme, this is a serious contender. It really started on June 11, 1963, with a Buddhist monk named Quang Duc. In order to protest the oppression of Buddhism by South Vietnam, he sat down in the middle of a street in Saigon and set himself ablaze.

Self-immolation has been a part of stories and legends since Sati, one of the wives of Shiva, set herself ablaze after her father insulted her husband. Most of the stories tell tales of women who are set on fire to honor a dead king or chief, but it's only fairly recently that it's become a form of horrifying protest.

In total, five monks self-immolated to protest the rule of Ngo Dinh Diem, and the practice continued through the Vietnam War. According to Time, 13 monks self-immolated to protest the war in a single week, and one man — Norman Morrison — even did it on the grounds of the Pentagon, while holding his own child (who survived). Since then, it's been done to protest Soviet invasions, job quotas in India, and according to NY Books, dozens of Tibetans — including at least seven underage children — have self-immolated or attempted to do so in resistance to Chinese rule, the oppression of the Dalai Lama's teachings, and the destruction of Tibet's landscape. Some have survived, only to disappear.

The Birmingham Children's Crusade

It's said that children are the future, and in May of 1963, the children of Birmingham, Alabama stood up in resistance to the idea that racism was there to stay. Martin Luther King, Jr. called them (via The New Yorker) "the disinherited children of God," and they did an incredible thing. On May 2, Biography says it was thousands of teenagers and children that gathered to march in protest of segregation and in resistance to the acts of horrible violence that had shaken the community in prior months.

Their resistance movement was a parade, and the consequences were brutal. Hundreds were arrested on the first day, and on the second day, law enforcement turned up and turned fire hoses on the kids. Others were beaten with batons, and then they released the police dogs. The youngest children were just 6-years-old, and those that still had their freedom continued their resistance for days. They sang songs, marched through downtown Birmingham, and all the while, videos and photographs were sent around the world.

Even as the school board promised to expel all the students that had been involved with the march (a decision overturned by the courts), Birmingham desegregated businesses and freed those who were arrested.

Mohism: avoiding war by making all equal

For just a few hundred years in ancient China, the philosophical movement of Mohism flourished. Between 479 and 221 BC, the followers of Mozi (also known as Master Mo or Mo Di, notes the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) did all they could to obey and spread the teachings of their founder. Among those teachings were the beliefs that morality was defined as actions that benefited everyone else, and that the ideal was to exist in a state of peace and harmony. It was a difficult position to take during a time in history referred to as the Warring States era, and Mohists promoted their ideas in a very hands-on way.

According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, Mozi was a skilled craftsman. Initially, his livelihood involved building instruments of war, but the more bloodshed he saw, the more firmly he believed it was nothing more than a waste of life. So, he started traveling from one state to the next, building fortifications. After fortifying one area, he would move on to the next and tell them just how futile attacking their neighbors would be.

Unfortunately, his efforts really didn't work. While his methods of resisting conflict by building defenses were mostly ridiculed, he did ultimately set up a school of philosophy and carpentry to help spread his message of peace, so that counts for something.

Denmark's Protest Pigs

Denmark and Prussia had a history of border disputes, and things really came to a head in the 1860s, after the end of the German-Danish War. The Prussian victors decided it wasn't enough to win, but they were also going to pass a series of laws that restricted displays of Danish pride in their newly conquered lands.

Many of the people who lived on lands that now belonged to Prussia weren't thrilled with the idea of being told they could no longer be proud to be Danish, so they came up with a brilliant way to display their country's colors: on the backs of pigs. With just a bit of selective breeding, Mental Floss says they were able to take red pigs and create a new breed that was defined by the white band around its shoulders — a pattern many might recognize as being similar to the Danish flag. It wasn't until the 20th century that these undeniably flag-striped pigs became recognized as an official breed, the Husum Red Pied. Denmark's "protest pigs" are, unfortunately, endangered, with less than 75 remaining as of 2019.

Gandhi's incredible Salt March

Everyone knows the name of Gandhi, and everyone knows that he was a massive proponent of peaceful resistance. But what did he actually do? Well, in 1930, the Indian National Congress renewed their push for independence, and History says that's when Gandhi decided on salt as the unlikely vehicle for his campaign. Since the 19th century, India's British occupiers had closely regulated the production and trade of a number of things — including salt. Indian manufacturers were forbidden from making it or selling it, and were instead forced to buy it at insane prices from the British. Considering it was a necessary part of everyone's diet, it was a universal cruelty.

So, Gandhi and some of his followers set out, walking about 12 miles a day until they reached the coast. Thousands of people joined along the way, and the march stretched for miles. An impressive 241 miles later they reached the beach, where representatives of the British had ground hunks of salt into crumbs. Still, Gandhi found a salt rock, held it up, and denounced the British Empire.

From then on, it was open season on salt. People started extracting and selling it themselves, and somewhere around 80,000 people — including Gandhi — were arrested in the chaos that resulted. A year later, British officials agreed to meet with Gandhi and end their control over salt.

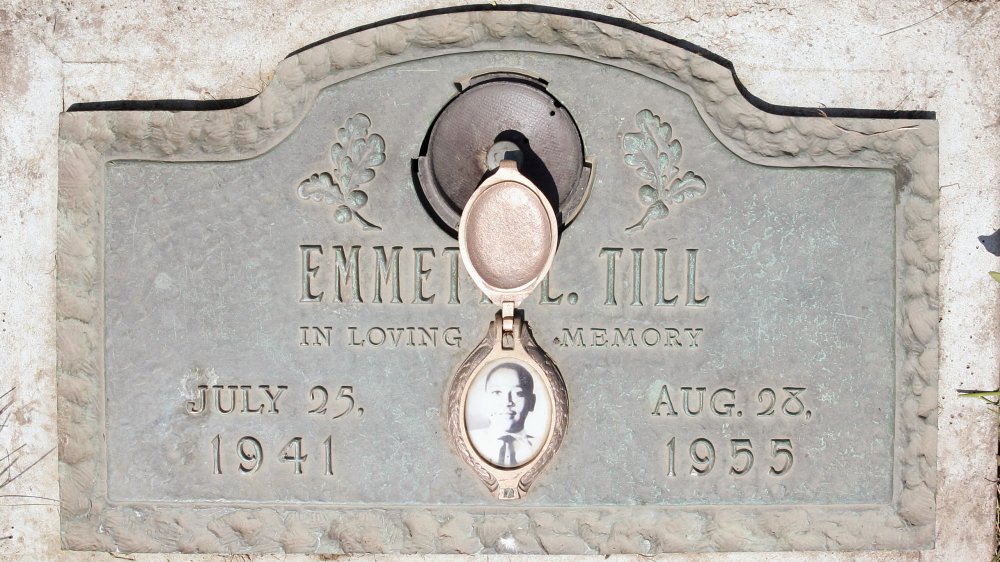

Emmett Till's open casket

Emmett Till was from Chicago, and during the summer of '55 he was visiting family in Mississippi. He was 14-years-old, says Vanity Fair, and he went into a store to buy some bubble gum. That's when... something happened. What? It's impossible to tell. One story is that he whistled at a white woman named Carolyn Bryant Donham, who would later testify that he had shoved her and threatened her, too. She would later admit that was a complete fabrication, and the whistling might have been untrue, too — Till had a lisp. Regardless of what happened then, what happened next was infinitely worse.

According to the Civil Rights History Project, Carolyn's husband and brother-in-law kidnapped Till, then beat, bludgeoned, and shot him to death before dumping his body in the Tallahatchie River. When his body was recovered he was nearly unrecognizable, but according to Time, his mother said, "Let the people see what I've seen." She insisted on an open casket, and not only did tens of thousands of people come to pay their respects, but the photos of the teen's battered face brought the struggle for civil rights into stark focus.

The men who killed Till were acquitted, but the image of his body was front and center with people like Rosa Parks, who later said they found the courage to do what they did because of Emmett Till and one mother's determination that everyone would see her son.

The Singing Revolution and the Baltic Chain

How hard is it to stand up and sing the most patriotic song that you know? Now, imagine how hard it would be to do that very same thing, only to do it while there's a tank bearing down on you. Estonia had long been under the thumb of the Soviet Union when, in the mid-1980s, they decided to use their rich cultural history as a weapon against their oppressors. According to the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict, doing things like flying the Estonian flag and singing traditional songs had been banned by the Soviets — and they decided to do it anyway in what was called The Singing Revolution.

And it was huge. Around 300,000 people — a quarter of the country's population — gathered at a single festival in 1988, and they didn't just sing — they called for independence. A year later, around 700,000 Estonians would join others in the Soviet-controlled Baltic nations to join hands — literally — as a show of solidarity and resistance.

According to PRI, around two million people joined hands to form what was the longest human chain in history, stretching for 400 miles through Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, and through their capital cities. And the statement made a huge difference: independence came in 1991.

The peaceful protests of Parihaka

From where it sat at the base of New Zealand's Mt. Taranaki, the settlement of Parihaka became known as a center of resistance. It started with leaders Te Whiti and Tohu, who guided the Maori on a peaceful resistance against the Europeans who had seized the lands they had lived on for generations. At the heart of their resistance? Plowing.

According to New Zealand History, it started in the 1860s when the Maori started plowing and fencing the lands that had been traditionally theirs. Many were arrested, but resistance continued — until November 5, 1881. That, says the New Zealand National Library, is when the Native Affairs Minister ordered an invasion of Parihaka. The armed militia was greeted by singing children and women who offered them bread. And it didn't make any difference — their settlement was destroyed, their crops were stolen, and their leaders were imprisoned.

For a long time, it was simply forgotten. It wasn't until 2017 that authorities went back to Parihaka, offering a formal apology and reconciliation.

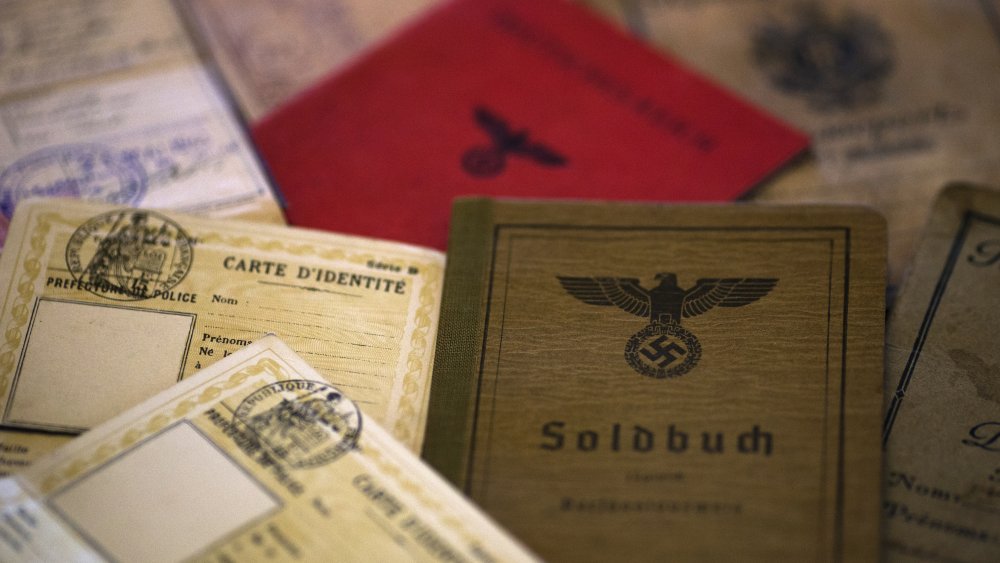

Adolfo Kaminsky: the great forger

Adolfo Kaminsky spent much of his life as a forger, and he put those skills to good use, starting when he was just 18-years-old. That's when Kaminsky set up shop in Nazi-occupied Paris, and began using his apartment to forge documents for families who were on the verge of being sent to the concentration camps.

His involvement started in 1943, when he and his family were sent to Drancy, on their way to the camps. Fortunately for the family, they had passports from Argentina — and the government protested their arrest. They were released, and when they got false documents, his skill at removing ink — skills he had learned while working at a dairy — got him an invitation to join the Resistance. He did, and spent the war years forging everything from food stamps to passports, sometimes at a rate of 30 documents each hour. He never took a dime, and saved thousands of lives. He never told anyone about it, either — according to The New York Times, the 91-year-old's neighbors didn't even know what was so special about him ... in 2016.

After the war, he continued forging documents for others in war-torn countries from Algeria and South Africa to Vietnam. He did it all because of one belief: "I saved lives because I can't deal with unnecessary deaths — I just can't. All humans are equal, whatever their origins, their beliefs, their skin color."