The Biggest Lies These Biopics Told You In The Past Decade

One of the most tried and true movie genres of the past few decades: the biopic. These movies tell the life story — or a single important event in a life — of a famous or notable individual. And oh boy, with how many of them are out there, it seems like everyone gets biopic treatment at some point. The problem is, even famous people don't necessarily have lives that follow standard character arcs and hit all the right emotional beats. This is a problem for filmmakers.

Biopics are based on a true story, but they're rarely (if ever) entirely a true story. Film is a completely different medium than the non-fiction books many of these movies are based on, and they're certainly paced a lot differently than reality. Screenwriters and filmmakers have to take a life story and juice it up — embellish details, compositing similar people into a single character, truncating events, or leaving out major things entirely so as to fit narrative structure as well as a standard movie running time of around two hours. Hey, they're spending millions to make a movie here, and hopefully get a couple of Academy Awards out of it. They just can't let something like facts get in the way of telling a good story. Here are some of the most successful and most popular based-on-truth movies of the 2010s ... and how they brazenly lied to your face.

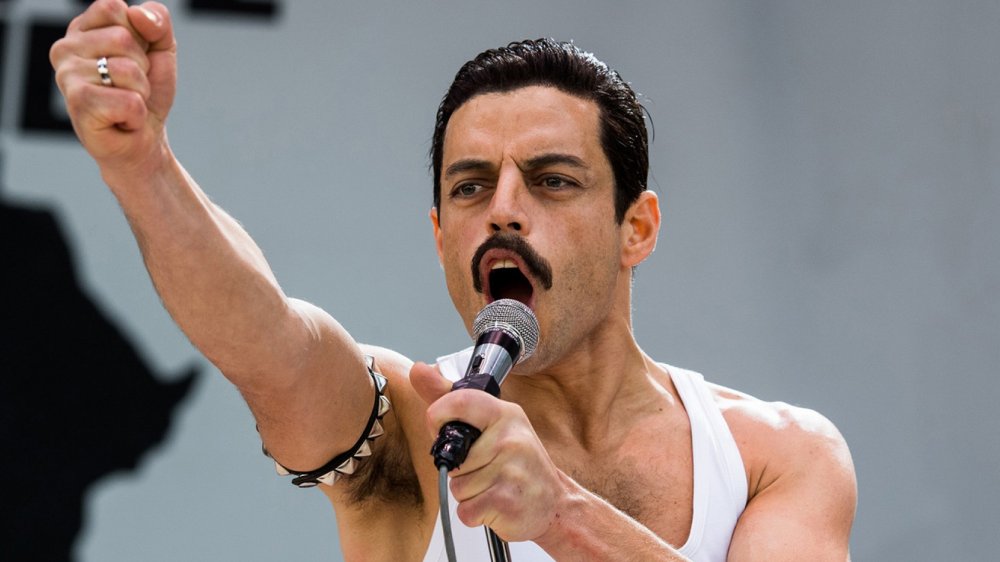

Bohemian Rhapsody is the Queen of fibbing films

Bohemian Rhapsody focuses on Freddie Mercury (Rami Malek), the charismatic, supernaturally voiced lead singer of Queen. It's natural that filmmakers wanted to place the most attention on the late, larger-than-life Mercury, but it was also practical because the band history of Queen doesn't contain nearly as many big, dramatic moments as Bohemian Rhapsody may claim.

The film shows Queen originating after Mercury introduces himself to Brian May and Roger Taylor, guitarist and drummer, respectively, of the band Smile, and gives an impromptu audition. When Mercury actually joined those guys, they were his roommates. Then there's the matter of Queen splitting up so Mercury could selfishly and arrogantly pursue a solo career. But Queen never broke up; sure, they took a hiatus in 1982, but that was so all the band members could go off and record their own stuff. By 1984, they'd released the album The Works and toured throughout 1984 and 1985 to promote it. That emotional sequence where the band let bygones be bygones to reunite for a triumphant appearance at Live Aid in the summer of 1985? That was just another gig, and business as usual.

Sniping on American Sniper

Most contemporary war movies made in the last decade or so — think Thank You For Your Service and Brothers — downplay the action and pro-America politics to instead focus on the psychological impact of combat on military personnel. Clint Eastwood's 2015 drama American Sniper, based on the memoir of the same name of highly decorated Navy SEAL sniper Chris Kyle, delves into those areas a bit, but also provides compelling and frighteningly realistic scenes that aim to imitate actual war zone scenarios. However, Eastwood and his team fudged the details here and there to craft scenes that are somehow even more harrowing than the events from Kyle's real life.

The film opens with Kyle (Bradley Cooper) keeping armed watch over a street in Iraq where a Marine convoy is about to pass through. He spots a woman hand off a massive anti-tank grenade to a little boy, who goes running at the convoy. Kyle has no choice but to take the kid out. In his memoir, however, Kyle makes no mention of a child, only a woman holding what was likely a much smaller, less destructive grenade. Then there's the de facto villain of the film: an Iraqi sharpshooter named Mustafa (Sammy Sheik), who crosses paths with Kyle a few times in American Sniper, including a only-one-man-lives final battle. Kyle only mentioned him in on paragraph of his book, saying he never saw Mustafa personally, and "other snipers later killed an Iraqi sniper we think was him."

Rocketman got its dates incredibly wrong

There's a Broadway theatrical style called the "jukebox musical," in which well-known, pre-existing songs tell the story, as opposed to ones written solely for a production. The 2019 film Rocketman is a Elton John jukebox musical disguised as a music biopic, utilizing the vast catalog of its subject's songs to tell the story of the man's rise to fame, his wild success, and almost losing it all due to addiction and mental health issues, while ignoring the timeline when it's inconvenient.

John (Taron Egerton) is shown writing or recording certain songs in a completely different years than he actually did, so as to emphasize dramatic beats. For example, he records "Don't Go Breaking My Heart," a #1 hit in 1976, and then he plays a legendary show at Dodger Stadium, which happened in 1975. Not long after he's recording the 1979 album Victim of Love while wearing the sequined hat he rocked in the late '80s. While making that LP, he decides to marry sound engineer Renate Blauel, an ill-fated idea that didn't go down in real life until 1984. And when John finally gets sober around 1990, the revitalized performer goes off and writes "I'm Still Standing." That song came out in 1983, and so it isn't really about the singer's new outlook on life at all.

The lies in The Revenant are pretty wild

Leonardo DiCaprio won an Oscar for his performance in The Revenant as Hugh Glass, who in 1823 was left for dead in the Dakota region by fur trappers after a brutal grizzly bear attack. That "rev" could also refer to "revenge," because as Glass brutally struggles to regain his wherewithal and health, the film turns into a tale of vengeance.

Glass sets out to kill John Fitzgerald (Tom Hardy), the man responsible for the death of Glass's son. In the movie, they enjoy a climactic showdown that ends in Fitzgerald's death from a scalping (but not by Glass's hand.) In real life, Fitzgerald didn't die in this manner. In 1824, he enlisted in the army and served for five years. While he was stationed at Fort Atkinson, Glass encountered him, but didn't kill him — he did, however get back his gun that Fitzgerald had taken when he'd left Glass to die.

There's actually no evidence that Glass was married to a woman from the Pawnee group of Native Americans, nor that he and this probably fictional woman (portrayed by Grace Dove in the film) had a son together. Her spirit visits Glass as he nears death at the end of the film, which also didn't happen in 1823. Glass recovered from his bear attack and returned to work in the fur industry. He actually died a decade later, in 1833.

Hey Canada, thanks for making Argo possible

Argo is about the making of a movie that doesn't exist ... nor was it ever supposed to. The Oscar-winning film tells of how the C.I.A. extracted six American diplomats held hostage in Iran in 1979 by staging a fake movie production. Pulling from the memoir of C.I.A. agent Tony Mendez (portrayed by Affleck in the film) and a Wired article by Joshuah Bearman, the film paints the C.I.A. in a very heroic and lone-wolf light. But getting those six people out of Iran was only partially thanks to the C.I.A. — it was almost entirely the doing of Canadian government operatives, so much so that until the release of Argo, this moment in history was known as "The Canadian Caper." After the events went down 40 years ago, Canada ironically received full credit, while American involvement was actually downplayed so as to protect the C.I.A. from reprisals.

As shown in Argo, the Americans were housed in Iran by Canadian ambassador Ken Taylor (Victor Garber). A Canadian Embassy worker named John Sheardown did that too, but he wasn't even a character in the film. It was Taylor who helped hatch the escape plan, while other Canadian government officials were the ones who did things like scout Iranian airports and secure exit visas. Even Jimmy Carter, president of the United States at the time, gives all respect to Canada. In 2012, he told CNN's Piers Morgan that "90 percent of the contributions to the ideas and the consummation of the plan was Canadian."

Saving Mr. Banks came with many spoonfuls of sugar

Ostensibly, Saving Mr. Banks is about the Walt Disney Company's attempts to turn P.L. Travers' Mary Poppins books into a big-screen movie musical. Travers (Emma Thompson) is extremely and openly reluctant to let anybody touch her beloved work because, as many flashbacks in Saving Mr. Banks let us know, the first Mary Poppins tale — with its redemption of Mr. Banks into a family man — is really about Travers finding peace with the memory of her alcoholic father (Colin Farrell). Thanks to the kind but relentless persuasion of Walt Disney himself (Tom Hanks), the author relents and the 1964 film Mary Poppins goes into production. Saving Mr. Banks depicts Travers attending the film's star-studded public premiere ... and sobbing her way through the screening as a cathartic release.

While the crying did happen, the reasons are different than presented in the movie. Seeing Mr. Banks reconnecting with his kids up on screen didn't give Travers closure and peace with her long-dead father. "It was such a shock, that name on the screen, Mary Poppins. So sudden. It hardly mattered, then, that her name was in such small type, listed as a 'consultant' at first, then in the line 'Based on the stories by P.L. Travers,'" wrote Valerie Lawson in Mary Poppins, She Wrote: The Life of P.L. Travers (via Vulture). She was still upset about the adaptation and Disneyfication of it all ... which certainly wasn't going to be shown truthfully in Saving Mr. Banks, a movie made by Disney.

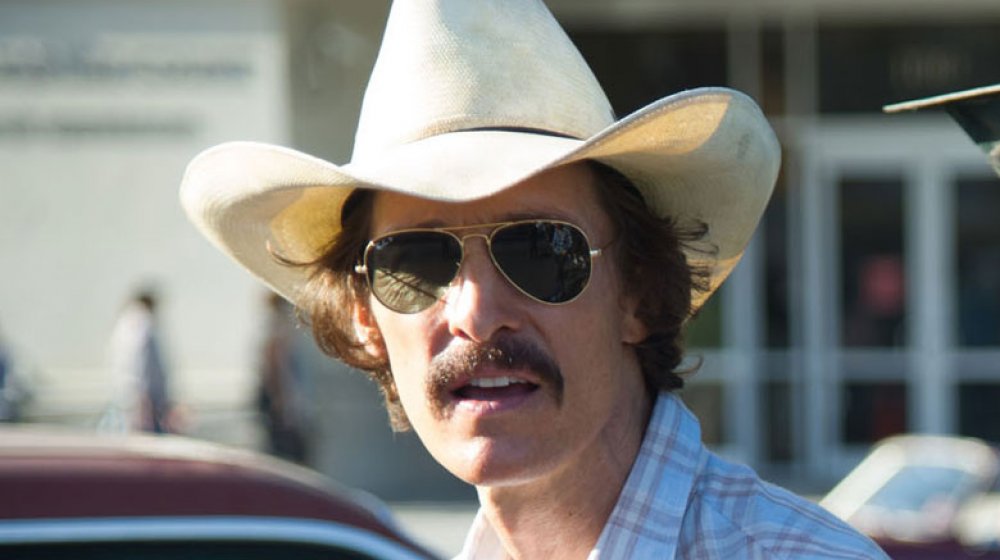

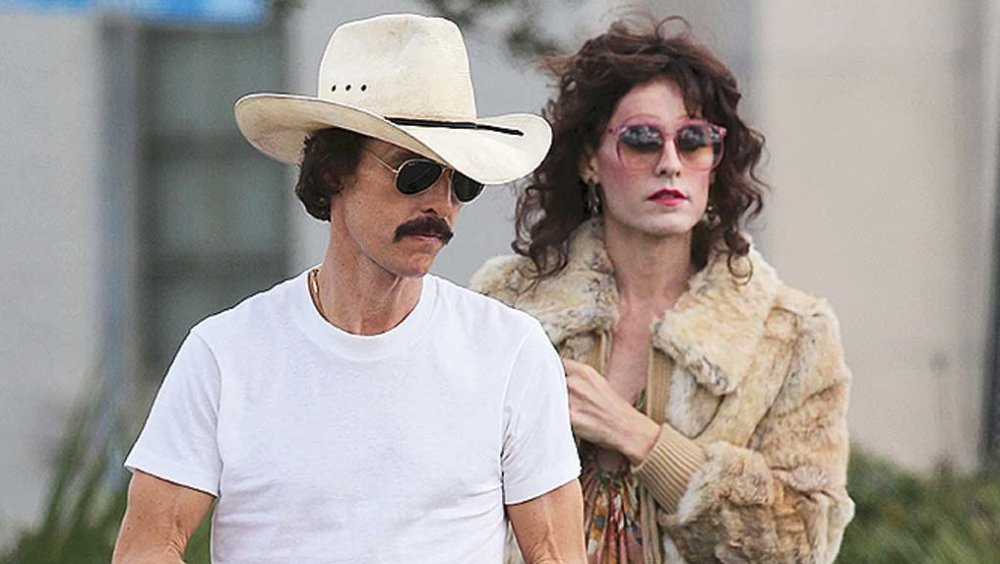

Dallas Buyers Club is the true story of fake people

The makers of the Texas-set Dallas Buyers Club cast actual Texan Matthew McConaughey in a role that would elevate his career and change his life. He won an Academy Award for his portrayal of Ron Woodroof, a rodeo-riding, hard-partying, promiscuous macho man who around 1985 tests positive for HIV, the virus that leads to AIDS. Virtually a death sentence at the time, doctors give Woodroof about a month to live. Unable to get into a clinical trial for a promising drug called AZT, Woodroof starts an operation (the Dallas Buyers Club) to smuggle such experimental and possibly life-saving HIV and AIDS drugs into his community.

While Woodroof was apparently a colorful character who really did bring new medicines (and hope) to a lot of people, many elements of Dallas Buyers Club are movie-building fantasy, created by screenwriters to provide a narrative arc and emphasize parts of the Woodroof character. In reality, Woodroof's doctor was a man named Steven Pounders, not a woman named Eve Saks (Jennifer Garner). She's there to be somebody with whom Woodroof can flirt, confirming the idea that he's aggressively heterosexual. That's an important distinction to make — in the 1980s, HIV and AIDS were still largely associated only with homosexual men. To that end, Woodroof (who friends say had relationships with men and women in real life) is very homophobic, but he ditches that attitude by the end of the movie through his friendship with a transgender woman named Rayon (Jared Leto). Like Eve Saks, Rayon wasn't a real person either.

The movie Captain Phillips was great; the man, maybe not so great

Captain Phillips tells the absolutely terrifying tale of Captain Richard Phillips, a humble, regular guy who in 2009 accidentally steers his cargo ship, the Maersk Alabama, into pirate-controlled waters off the coast of Africa, before heroically ensuring safety for all (eventually).

However, according to some of those crew members, the depiction of Phillips as a hero is entirely false. "Phillips wasn't the big leader like he is in the movie," said one crew member, anonymously, in the New York Post. Following the hijacking ordeal, 11 members of the crew sued Maersk Line and the Waterman Steamship Corp. over "willful, wanton, and conscious disregard for their safety" that were the doing of Phillips. According to the crew's attorney, Deborah Waters, those ship staffers pleaded with Phillips to not get so close to the coast of Somali, where pirates thrived. "He told them he wouldn't let pirates scare him or force him to sail away from the coast," Waters said. Phillips also allegedly completely disregarded anti-piracy protocol plans that had been written up for him. "He didn't want anything to do with it, because it wasn't his plan," added the anonymous the crew member. "He was real arrogant."

You could fill a book with the errors in Green Book

The Academy Awards named Green Book the Best Picture of 2018. It's the story of the friendship that develops between African-American pianist Dr. Don Shirley (Mahershala Ali) and his Italian-American driver Tony Vallelonga (Viggo Mortensen), on a concert tour through the segregated South in 1962. Screenwriter Nick Vallelonga — Tony's son — based his script on anecdotes of the trip told by his father, with little to no input from Shirley's family. Shirley's brother, Maurice, went so far as to call Green Book "a symphony of lies."

There are indeed historical errors. The exact locations and dates of the film's events were heavily changed, on account of how the trip lasted over a year, and not, as the film suggests, two months. Nor was Dr. Shirley estranged from his only brother. The musician had three brothers, with whom he spoke regularly.

In one sequence, a racially-charged argument with a policeman in Mississippi leads to physical violence, and Tony and Dr. Shirley are jailed. They're released when Dr. Shirley places a call to a powerful friend: U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy. According to Dr. Shirley, the corresponding real-life event went down in West Virginia, when a policeman stopped the duo for going 35 mph in a 25 mph zone, but claiming they were doing 75. There were no fisticuffs, and only Vallelonga was arrested. Dr. Shirley didn't have enough cash on hand to post bail, so instead of getting some money wired, he called Kennedy.

As if BlacKKKlansman wasn't unbelievable enough already

Most based-on-a-true-story movies are dramas, because historic, high-stakes events are often very serious things. But sometimes certain occurrences are just so absurd that filmmakers can't help but make the movie retelling the events into a comedy. That's what happened when Spike Lee co-wrote and directed BlacKKKlansman. It's based on the memoir Black Klansman by retired Colorado police officer Ron Stallworth (portrayed by John David Washington), an African-American man who managed to infiltrate and expose local operations (and criminal activity) of the white supremacy-touting Ku Klux Klan in the 1970s.

It sounds made up, if not impossible, but Stallworth would deal with KKK personnel on the phone, while a white law enforcement colleague attended in-person meetings and events. That's all real, although Flip Zimmerman, the white detective portrayed in BlacKKKlansman by Adam Driver is an invention — in his memoir, Stallworth gave the policeman the fake name of "Chuck." Also made up: the love interest. Stallworth didn't date a politically active woman named Patrice Dumas during the time of his involvement with the KKK (which happened in 1978, not in 1972 like the movie presents).

During his investigation, Stallworth becomes something of a mentee to national Klan leader David Duke (Topher Grace). Late in the film, Stallworth exposes and humiliates Duke telling him he's been duped by an African-American man. In real life, Duke didn't know that Stallworth wasn't who he said he was until 2006.