The Most Bizarre Unsolved Mysteries Of World War I

World War I, though overshadowed for some modern observers by its even bloodier sequel, stands as a turning point in history. Empires shattered, millions of people died, many more were injured, and warfare changed forever due to the new weapons and strategies deployed over the course of the conflict. Borders in Europe and the Middle East were redrawn, new countries were born, and sadly, the seeds of further (and in some cases, ongoing) conflicts were sown. (In the thin-silver-linings department, World War I also led to the popularization of the candy bar.)

Historians have continued to study World War I. Its apparently sudden outbreak and enormous scale smashed the elegant Belle Epoque period that preceded the carnage. But even after over a century, some mysteries about the war persist. The diversity of the people involved in these unanswered questions points to the enormity of the conflict: Artists, murderers, spies, scholars, and even grand duchesses were all swept up in the maelstrom that consumed so much of the world.

What did Colonel Redl tell the Russians?

In May 1913, the counterespionage service of Austria-Hungary caught a very big fish indeed: Its own empire's chief of intelligence. Colonel Alfred Redl had been caught receiving envelopes of money from addresses abroad that were known to be used by Russian spy networks. Confronted, Redl confessed to a long career of treason — primarily but not exclusively in the service of Russia — from as early as 1902. He was left alone with writing supplies and a revolver. He used them both, dying by suicide after penning a farewell letter. The devoutly Catholic emperor Franz Josef disapproved of the decision to allow Redl to die in mortal sin. The more pragmatic military establishment would have preferred a chance to interrogate him, perhaps even using the blinding floodlights Redl himself used when asking hard questions.

Redl's seemed to have committed treason purely for money. While he was gay (or at least had same-sex relationships), this was an open secret to everyone except the Russians, who apparently didn't know that one of his vices they were funding was men. Blackmail was only an indirect motive, as Redl needed to pay off lovers threatening to make their secret far more open.

Historians continue to assess how badly Redl's treason damaged Austria-Hungary's war effort. He certainly had access to effectively all of the empire's significant military plans and secrets, and he died without giving a full accounting of what he had told his Russian handlers and potential other clients in France, Italy, and Serbia. Austrian plans changed as the war went on, and with both empires collapsing under the strain of the conflict, there was no ultimate beneficiary to the Redl affair.

What happened to Bela Kiss?

Bela Kiss was a catch. Handsome, employed, and intelligent, he had educated himself without attending school and was known by his neighbors as a good conversationalist. He divided his time between a primary residence in Cinkota, a town outside Budapest, and an apartment in the capital. Age 37 in 1914, Kiss had taken his time choosing a missus, and was single when he went off to fight for Austria-Hungary.

By 1916, Kiss was very, very late on his rent, and his landlord feared he'd been captured or killed in one of the empire's meat-grinder warfronts. When this landlord went to evaluate the property, he found, to his horror, a number of metal drums containing the corpses of strangled women. The bodies had been preserved in wood alcohol, a toxic industrial chemical. The drums had aroused suspicion (of bootlegging) when they arrived; Kiss had reassured his neighbors that he merely intended to stockpile gasoline in the event of war. Papers in Kiss's study indicated that he had corresponded with some 174 women intending to defraud them, proposing to 74 and murdering at least 30, based on the remains found around the property.

Kiss was traced to a hospital in Serbia, but he was able to skedaddle before being caught. Rumors placed him in a Romanian prison, a Turkish cemetery (dead from yellow fever), and walking free on the streets of the United States. No sighting of Kiss was confirmed after 1916. His later life, and any subsequent murders, remain a mystery, and Kiss remains a particularly disturbing figure in the rogue's gallery of the most wanted criminals who were never caught.

What was lost in the library of the University of Leuven?

On the eve of World War I, Germany sat between two allied military powers: Russia and France. Germany knew that a two-front war could be devastating, and so the empire's military logic dictated that, in the event of war, France was to be smashed with a knockout blow to free up German men and materiel to face the Russian juggernaut. This plan involved sweeping around the heavily fortified Franco-German border and through Belgium, whose neutrality had been guaranteed by European powers, including the German Empire's predecessor, Prussia.

When Belgium refused free passage to German troops at the outbreak of war, the Germans, enraged and in a hurry to enact their plan against France, embarked on a savage campaign of reprisals subsequently called the Rape of Belgium. One of the worst crimes against culture committed by the advancing Germans was the burning of the library at the Catholic University of Leuven, a repository of countless historical and valuable books. The holdings were still being catalogued, so the losses cannot be tallied, but we do know that medieval manuscripts and some of the earliest printed books in Europe were among the lost.

The rest of the world was so outraged that a German responsibility to rebuild and restock the library was written into the Treaty of Versailles. When the Germans returned in 1940, they burned the library again, but the repeated crime was overshadowed by even worse German and Axis actions across Europe. Today, the library has again been rebuilt, even as some historians seek to blame the Belgian resistance for the blazes.

Where are the Romanov jewels (and Russian state gold)?

In addition to bearing a paragraph's worth of titles and ruling a colossal empire, the Romanov tsars of Russia were absolutely loaded. In 1917, the imperial family controlled an estimated $45 billion in cash and assets. (In an absolute monarchy like the one the Romanovs helmed, separating the royal family's property from that of the state is not necessarily easy.) Of course, by the end of 1918, Tsar Nicholas II and his immediate family were dead (future alleged Anastasias notwithstanding), and most of the rest of the family had fled the Bolshevik takeover of Russia. And one of the most enduring mysteries about the fall of this glittering dynasty has always been, put bluntly: Who got the loot?

Land was snapped up by the emerging Soviet state, as was much of the movable jewels, gold, and valuable art pieces like Faberge eggs. The Soviets sold many of these assets abroad, as even a worker's paradise will face start-up costs. Other pieces were smuggled out by opportunists or persons hoping to aid the Romanovs or a restoration effort. But as one might expect from movable wealth in a time of chaos, it hasn't all been found.

One theoretical bonanza is the remaining imperial gold reserves, which had been sent from St. Petersburg to Kazan for safekeeping in the early days of the Russian Revolution. The loot then went farther east to Irkutsk in Siberia, where the Red Army took control of it and sent it back to Kazan. Or at least most of it. Or some of it. Historians differ on whether all the gold was accounted for, and local legends place some of it still hidden in Siberia or at the bottom of chilly, beautiful Lake Baikal.

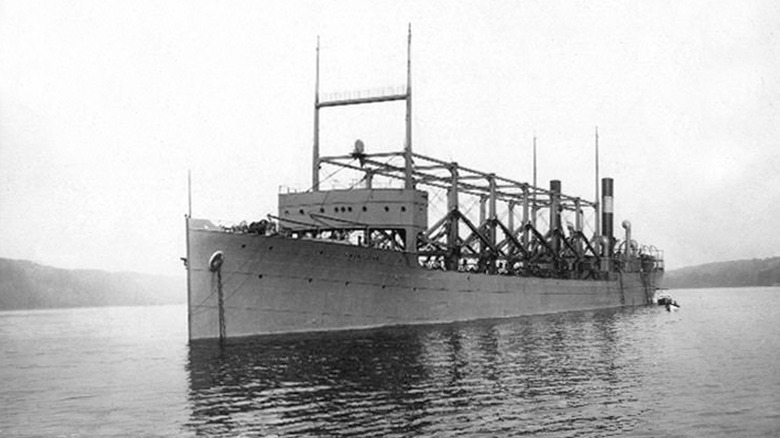

What happened to the USS Cyclops?

The disappearance of the USS Cyclops in 1918 remains the worst noncombat loss of life in the history of the U.S. Navy. The Cyclops was a collier, meaning a transport ship designed to shuttle coal and thus support steam-powered warships (though they could and did handle other cargo). Initially civilian-crewed, with the entry of the United States into the war in the better-late-than-never year of 1917, support ships like the Cyclops were brought under direct naval control, with military officers in charge.

In early 1918, the Cyclops was sent to Brazil with a load of coal, which it was to offload in Rio de Janeiro before taking on a load of ore for transport to Baltimore. The ship left Bahia, in Brazil's northeast, on February 15, called at the island of Barbados on March 3, and then ... poof. The ship never arrived, and no trace of it has been found in the century since its disappearance.

While German submarines did prey on Allied shipping, no U-boats were reported in the area, and an attack on the Cyclops does not appear in any available records. A more credible theory is that the crew was unfamiliar with the safe transport of the heavy manganese ore it was hauling, and if this material had been loaded improperly, it could have cracked open the hull and sank the ship. Other theories, with varied degrees of credibility, point to poor command (and thus a possible mutiny), damage to one of the ship's propellers and cascading failures from such a fault, cryptids, or the actions of whatever entity or force leads to the disappearances within the Bermuda Triangle.

Who was the artist JM?

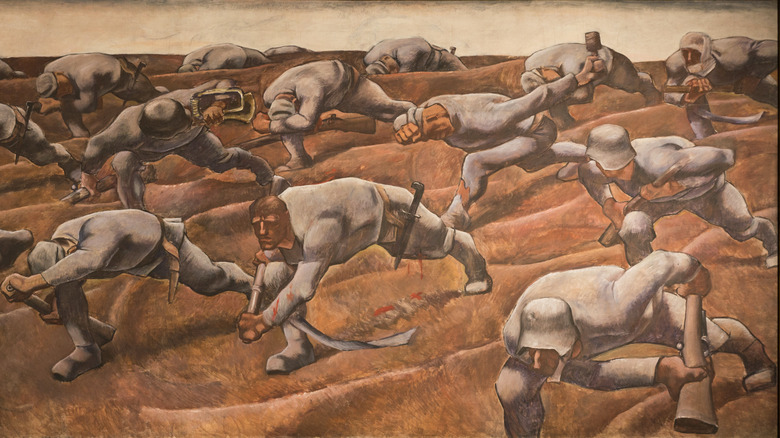

The traumatic experiences of World War I inspired a number of artists to respond, especially those who had served in the war. Poets, novelists, musicians, and visual artists all produced work reflecting their experiences and the broader horror of the conflict. Some of these works are made far more poignant by the artists' deaths in battle, while one particular body of work has emerged as an enduring mystery, as its artist has never been identified.

The University of Victoria, British Columbia holds two beautifully illustrated wartime journals of uncertain provenance. They are believed to have been in the university's collection since the 1960s and are signed only with the initials "JM." Full of watercolor and pen-and-ink illustrations reflecting technical skill and a strong artistic eye, the journals hold a few clues to the artist's identity but no slam-dunk answers. He served with the Royal Horse and Royal Field Artillery in France and Belgium in the last years of the war, had at least one daughter he addressed as "Adele," and, happily, survived the war: The last entry is from 1920. Despite this information and the university placing the entirety of the sketchbooks online, no one has yet come forward with answers about the identity of this mysterious artist.

Was the Grand Duchess of Luxembourg a German sympathizer?

A less well-remembered casualty of the German advance against France in the early days of the war was the little country of Luxembourg. Ruled by Grand Duchess Marie-Adelaide, Luxembourg spent the 19th century bouncing between various schemes to reorganize the Low Countries. It ultimately wound up as a demilitarized, neutral, independent nation with its own grand duke (or duchess, as it turned out) in a customs union with Germany. Deep economic ties to Germany, cultural similarities, and the German roots of the grand ducal family put Marie-Adelaide and her country in a complicated position at the outbreak of war.

When Germany occupied the little grand duchy in 1914 as part of its attack on France, 20-year-old Marie-Adelaide and her government protested, but they couldn't do much else, especially when they saw the savagery with which Germany dealt with resistance in neighboring Belgium. Very, very imprudently, however, Marie-Adelaide received the kaiser, Wilhelm II, in Luxembourg, as her sister was going to marry the crown prince of Bavaria. This, combined with wartime propaganda against Marie-Adelaide as the head of a government that was not resisting German war efforts, led people to perceive the young grand duchess as very much in Germany's pocket.

After the war, faced with enormous public disapproval, Marie-Adelaide abdicated in favor of her sister, Charlotte, who led the little country through World War II. Marie-Adelaide entered a convent and died young in 1924. Whether her making nice with the Germans was a ploy to preserve her country or a reflection of her own inclinations can never be fully answered.

What were the Angels of Mons?

The first few weeks of battles on the Western Front — the Battle of the Frontiers — saw Germany occupy almost all of Belgium and a considerable chunk of northeastern France before being stopped uncomfortably close to Paris at the Battle of the Marne. One of the battles making up this opening phase of the war was at the industrial city of Mons in western Belgium, where British forces first clashed against the German army. The British were outmanned and forced to retreat, though arguably the delay they provided helped save Paris and with it, the war.

British soldiers who had escaped the attempted German encirclement at Mons later reported phantom archers armed with bows and arrows helping to cover their retreat, with German soldiers falling dead though no wounds were visible. Others saw apparitions of St. George, the patron saint of England, riding into battle on a white horse while yet more reported winged figures frustrated the German advance. These apparitions (and many others) were collectively termed the Angels of Mons.

The obvious answer is that dehydrated, exhausted, frightened men hallucinated or misinterpreted what they saw, either at the moment or in retrospect. The supernatural writer Arthur Machen claimed to have begun the legend with a short story he had written that had been published shortly after the battle, regarding... St. George helping the British Army at Mons. These logical but emotionally unsatisfying explanations have never fully quashed the legends, and the Angels of Mons have gone on to inspire artists, writers, and the tourism board of the liberated, rebuilt city of Mons.

What happened to the 5th Norfolk Regiment?

In 1915, the Allies attempted a straightforward if optimistic plan to knock the Ottoman Empire out of the war: They would just go seize Constantinople, the capital of the teetering realm. The resulting disaster was called the Gallipoli campaign, Winston Churchill's failed attack named after the landing site outside the city where the Allies established a beachhead and not much else. It led to over 200,000 casualties, many of them from members of the emerging British Commonwealth like India, Australia, and New Zealand. But one regiment of British soldiers straight from jolly old England herself simply disappeared: No dead, no captured, all gone save one wounded survivor.

The men of the 5th Norfolk Regiment were all from the area around the royal estate at Sandringham, still used by the British royal family as a country house today. During World War I, friends and neighbors often joined up and served together. The pro was instant camaraderie. The con was that disaster befalling a unit could rip the core out of a town or village. The 5th Norfolk arrived in the Ottoman Empire on August 10, 1915 and were ordered to advance on August 12. Equipped with bad maps, vague instructions, and insufficient water, attack they did that afternoon, never to be seen alive again.

Supernatural explanations have, as usual, been proposed. The more likely explanation is that the raw recruits were especially unlucky and were all killed, either in battle or by a Turkish army unwilling to bear the cost of prisoners. Remember, this is the same Ottoman government that was beginning its most recent genocide of Armenians. The post-war discovery of remains bearing Norfolk insignia around a ruined farm near where the regiment was last seen confirmed this interpretation for many, but not all observers.

Was the kaiser experiencing mental illness?

Kaiser Wilhelm II was the emperor of Germany and king of Prussia from 1888 until 1918, when he was one of the many European monarchs to lose his throne at the end of World War I. As the visible, eccentric figurehead of one of the clashing alliances, Wilhelm received a good deal of blame for the war, a perception helped by a reign full of erratic behavior that had nearly led to war at least once before. Was the kaiser experiencing mental illness, and had this instability led Europe to ruin?

The answer, of course, depends on who you ask and how you define mental illness. Diagnosing public figures is generally considered poor form for clinicians, if not malpractice, and evaluating the mental states of the dead comes with its own challenges. Nevertheless, during and after his reign, Wilhelm has attracted the attention of a number of armchair diagnosticians, labeling him as having narcissistic personality disorder, bipolar disorder, neurasthenia (an old-fashioned term more or less meaning chronic fatigue), and good old-fashioned madness. None of these diagnoses can, of course, be proven, but the fact that the discussion came up then and has lingered since does emphasize a key weakness of hereditary autocracy: Some people have kids unfit to rule.

If you or someone you know needs help with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.