The 5 Most Painful Ways To Die In The Wild West

The following article contains graphic descriptions of death and murder.

The Western United States between 1865 and 1900 was called "wild" for a very good reason. The frontier region was long on lawlessness and short on infrastructure, which meant people there often took matters into their own hands, by gun or by rope. Being shot by the large-calibre lead slugs of the time or hanged were two incredibly painful ways to die. Then there were the Native Americans who retaliated against white settlers encroaching on their lands, the slaughter of their people, and broken treaty after broken treaty. Dying by scalping was excruciating. It should be noted that going back hundreds of years, Anglo-Americans scalped Native Americans as much if not more than the opposite. In the mid-1600s, Willem Kieft, the governor of the Dutch colony New Amsterdam, offered bounties for the scalps of Native Americans deemed to be enemies.

Other horrible ways to go in the Wild West included dying by various diseases like typhoid fever and cholera, which came with agonizing symptoms and no known medical interventions at the time. Similarly, during the 19th century, snakebites were mostly fatal and always painful since antivenom wasn't invented until the turn of the century and didn't come into common use in the U.S. for several decades afterward. The Wild West offered a host of nasty ways to die, a far cry from the romanticized Hollywood vision of the era.

Death by gunshot

The image of the Wild West gunslinger has become an ever-present part of the era's mythology. But what doesn't often make it into most depictions is the horrific damage and accompanying pain the lead slug of the time produced. The typical revolver of the period was a .44 or .45 caliber that packed a real wallop and was deadly enough that it could kill no matter where it hit, whether shoulder or leg, much less chest or head. The soft-lead slug left a large and irregularly shaped path as it traveled through the body, smashing bone, ripping tendons, and severing arteries.

If you were able to get decent medical treatment — and in the Wild West, many doctors didn't even have medical degrees — there was the real possibility of them amputating a limb that had been damaged by gunshot. With only light anesthetics like chloroform available at the time, the patient would have to be held down from the pain during the operation. There was also the accompanying infection that could come from the slug, the uncleaned wound, or even the doctor's dirty hands or instruments at a time before antibiotics. This was as deadly as the wound itself and a slow, painful way to die.

Death by hanging sometimes took agonizing minutes

In the Wild West, judges were strict and justice swift. This is probably best personified in Federal Judge Isaac Parker, known as the "Hanging Judge" who sentenced 160 people to be hanged. Then there were the extrajudicial hangings by vigilante groups. Death by hanging was the go-to form of execution during most of the 19th century in the United States, even though it was known to be an extremely painful way to die. As far back as 1774, a Scottish anatomy professor, Dr. Alexander Monro, described the process as akin to having someone suffocate you with a pillow, saying that the victims are conscious of the fact that they're slowly being strangled to death. "The man who is hanged suffers a great deal," he wrote (via "The Hanging Tree: Execution and the English People, 1770-1868"). It could take up to several minutes for the victim to die.

Later, newer hanging methods came around, including the long drop and the upright jerker, which were designed to quickly break the neck. But even these methods were less than perfect. If the execution went wrong, the prisoner could have their head snapped off or worse — be slowly strangled to death.

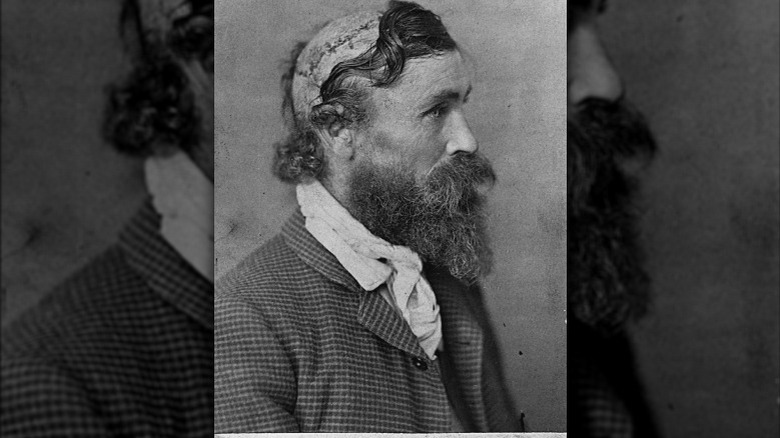

Scalping: A red-hot searing pain

The Native American tradition of scalping one's enemy in battle was a long-standing practice among various tribes from across North America going back at least to the 14th century. The Plains Indians tribes tended to scalp dead or sometimes on dying warriors, but in some instances victims survived. That was the case with a man named Herman Ganzio, who was among the Anglo-Americans who had broken a treaty and invaded the sacred Sioux Nation lands in the Black Hills of what is now South Dakota and Wyoming in search of gold. This triggered the Great Sioux War.

In the spring of 1876, Ganzio was attacked by a band of Native Americans about 70 miles north of Fort Laramie. The warriors shot him twice before catching up with him. One warrior held his hair tight and used a knife to cut away his scalp. "I felt a hot, a redhot, stinging sort of pain all around the top of my head — being torn out by the roots; it was too much; I couldn't stand it; I died — at least I thought I did," Ganzio later told a Kansas City Times reporter (via the Ann Arbor District Library). A counterattack prevented the warrior from finishing the job, and Ganzio suffered through a painful surgery and months of recovery. He was lucky, as most people didn't survive being scalped.

Waterborne diseases that killed quickly but painfully

Life in the 19th century (and earlier), before the medical breakthroughs of antibiotics and other life-saving drugs, meant even a minor wound or common disease could be very deadly. Among the ailments that folks living in the Wild West had to contend with were waterborne diseases like typhoid fever and cholera, which was one of the brutal ways to die while traveling on the Oregon Trail. Both cholera and typhoid fever are caused by bacteria and attack the victim's gastrointestinal system.

Cholera was spread through contaminated food and water and could kill within just a few hours, sending some victims into shock. The symptoms included searing stomach cramps, diarrhea, vomiting, muscle pain, and an unquenchable thirst before victims would begin convulsing and then die. Typhoid fever, also caused by infected food or water, left victims suffering from similar symptoms as cholera plus intense headaches, swollen abdomens, reddish lesions, and other issues that also often ended in death. And then there were other untreatable diseases such as smallpox, diphtheria, and tuberculosis. It was even worse for the Native Americans. It's been estimated that 95% of the Indigenous population died from infectious diseases caused by contact with European colonizers and later Anglo-Americans.

Death by snakebite

If you avoided dying in the Wild West from a bullet wound, swinging from the end of a rope, having your scalp sliced off, or succumbing to a waterborne disease, there were still snakes to contend with. In the Western U.S., there are several species of rattlesnakes, from the Western diamondback to the sidewinder to the Western coral snake. If you were bitten by any of these in the Wild West, you didn't have a great chance of survival. French scientist Albert Calmette developed the first antivenom (also spelled "antivenin") in 1895, but it wasn't produced in the U.S. until the late 1920s. Additionally, common snakebite treatments in the Wild West were often as bad if not worse than the bite.

Most rattlesnake venom contains a hemotoxin that attacks the blood and tissue, causing necrosis and internal hemorrhaging. Symptoms include difficulty breathing, among other problems, before organ failure after two to three days. The Western coral snake's venom includes a neurotoxin, which affects nerve function, producing symptoms like muscle twitching, paralysis, and often death. Some common treatments at the time included cutting into the wound and attempting to suck out the venom and then cauterizing it, which often produced a deadly infection at a time before antibiotics. So while it's fun to imagine what it would be like to have lived in the Wild West, the truth is a bit scarier.