Things About The Battle Of Dunkirk That Don't Make Sense

In 2010, The Guardian published an open thread, challenging their readers to answer: Do Britons still have the "Dunkirk spirit?" World War II has remained a defining conflict for the United Kingdom, and the Battle of Dunkirk was a pivotal moment in the war. An evacuation that was expected to save 45,000 men at the most ended up bringing 338,000 Allied soldiers safely to British soil. The heroism of the Allies even in retreat and the courage displayed by thousands of civilians who contributed to the evacuation are still widely celebrated in print, politics, and the silver screen. Christopher Nolan's 2017 "Dunkirk" remains the highest-grossing World War II film to date and was a passion project the director had nursed for decades.

The "Dunkirk spirit" might best be summarized by Winston Churchill's description of the evacuation: "A miracle of deliverance, achieved by valor, by perseverance, by perfect discipline, by faultless service, by resource, by skill, by unconquerable fidelity." Whether the U.K. could muster such a feat in the 21st century, the ideal that Dunkirk represents hasn't lost its hold over Britain and the West. And yet in some ways, the battle is a curious turning point in the history of World War II. The "Miracle of Dunkirk," as it's so often described, owed as much to chance as to courage. That it became such a boost for morale is more than a little at odds with the scale of defeat it represented for the Allies. And some decisions by the German high command are still questioned to this day. Read on to learn more about the strange twists in the Battle of Dunkirk.

The Allies blundered the war leading up to Dunkirk

It was perhaps impossible for the Allies to defeat Nazi Germany at any point prior to the Battle of Dunkirk. But the battle and evacuation were, in part, the culmination of a series of mistakes and blunders made by British, French, and Belgian forces. After the fall of Poland, Britain and France were reluctant to engage the Germans directly, leading to several months of a "phony war" before a blitzkrieg attack came for Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. Some 400,000 troops of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) — a fraction of what ultimately would have been needed — were stationed in Belgium to help repel the attack, and the French held overall command.

But the Allies were stuck in the past, their leadership wedded to outmoded methods of warfare and exhausted by internal strife. They also assumed that the German attack would come along the Maginot Line. Instead, they took Belgium through the Ardennes Forest, which the Allies had judged impossible to penetrate by tanks.

Once the Germans defeated the French, they were able to cut off the BEF from the bulk of Allied troops and disrupt the already poor lines of communication between armies. Per the U.S. Naval Institute, the Allies had no reserve of troops behind the front lines, something Prime Minister Winston Churchill was only belatedly informed of. By the time he knew, the situation was hopeless. What reinforcements the British did send weren't enough, and the BEF had no choice but to fight their way back to Dunkirk and hold out until the rescue came.

Hitler pulled back his assault at nearly the last minute

In the British press' rush to portray Dunkirk as a miraculous escape achieved by the pluck and gallantry of the Britons, a major contributing factor to the evacuation's success was overlooked. The Allies had time to pull off the rescue because the German advance on Dunkirk was halted on May 22, a move now considered one of the great mistakes of World War II. And the decision came from Adolf Hitler himself.

Why the Führer would order such a halt has long baffled historians. One theory suggests that he possessed a shred of sympathy for the Allies, or at least to the British. Per Louis C. Kilzer's "Hitler's Traitor," General Hans Jeschonnek claimed that Hitler considered the English and Germans to be kin, didn't want to humiliate the British, and resented Winston Churchill for not recognizing his restraint. But there's much in the surviving paperwork that casts doubt on these claims.

Others have argued that Hitler, not terribly insightful on military matters, grew paranoid about Germany's string of military successes. He feared that fortune would turn against him, and Hermann Göring took advantage of his leader's paranoia to influence the decision to halt the army's advance. For Göring, this meant a chance for the Luftwaffe to hog the glory by wiping out Allies alone. Still another theory holds that an Allied counterattack along the advance, doomed though it was, had a powerful psychological effect on Hitler and his field commanders, who felt compelled to deal with the resistance they met en route to Dunkirk.

Even with the halt, the Nazis thought the Allies were finished

Whatever Adolf Hitler's reasons for ordering the Germans to halt their advance on Dunkirk, he may not have felt it was urgent to keep the momentum going. As the Allies fell back to Dunkirk, Britain's continued resistance to the Nazis seemed very much in question. Winston Churchill was only just installed as prime minister, and his hold on the job was tenuous. As intransigent as Churchill was about appeasement, the Nazi high command knew that factions of the British aristocracy and political class were convinced that their country could not hold out and that it was better to make peace with Germany.

The British commanders in the field were, if not inclined to appeasement, similarly pessimistic. Lord Gort, leader of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), considered it inevitable that the bulk of his command and its artillery would be lost and confided in a captain that he felt he had led the British to their greatest military defeat. According to Ronald Atkin's "Pillar of Fire," Churchill later reported on the pensive mood in Westminster Abbey by May 26.

The self-defeating attitude of Britain was mirrored by German confidence. William L. Shirer, traveling with the German Army, published in The Atlantic that the mood in Berlin before the halt was celebratory. "The fate of the great Allied army bottled up in Flanders is sealed," he wrote. He also reported on a bet given him by soldiers that the army would push past the resistance into London within a matter of weeks. Churchill later mused that such overconfidence fed Hitler's decision-making regarding Dunkirk.

The British were caught off-guard by Belgium's surrender

As British and French forces fell back from the German advance, they were caught off-guard by the behavior of one of their allies. Just as they managed to fall back behind the Belgian army, King Leopold III of the Belgians surrendered to Nazi Germany on May 28. Contrary to some claims afterward, Leopold did not spring his decision on the Allies without notice. He had communicated through liaisons that he would likely need to surrender if Belgium's situation looked hopeless. But Leopold was poor at communicating the state of his army, and his decision still left the British and French shocked and outraged. What's more, he acted against the unanimous advice of his own government. They fled to London, and Leopold remained behind, a prisoner, until the end of the war.

Even before his decision to surrender, Leopold had been a puzzling and frustrating partner for the Allies. He and the Belgian commanders serving under him bungled communications with the British and French during the "phony war," confusing their partners as to what actions to expect from Belgium. Tensions with France reached a point where the French government tapped the phones of the Belgian embassy. But up until the surrender, Leopold's army fought valiantly against the Nazis. Bitterly resented by the leaders of Britain and France, he was eventually forced to abdicate for his son after the war. He in turn begrudged the charges that he'd betrayed the Allies, and he was estranged from the British royal family for the rest of his life.

A German tank division blew a chance to land a crippling blow on the Allies

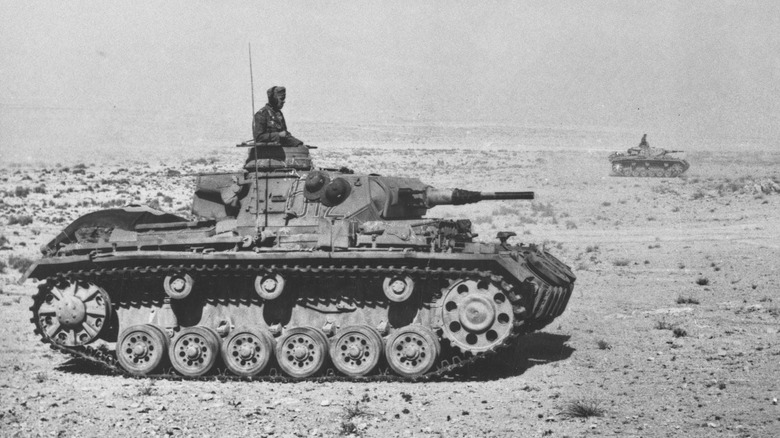

The decision to halt the German advance on Dunkirk came from the highest rung in the Nazi command ladder, Adolf Hitler. His choice has invited considerable scrutiny, and it's considered one of the biggest mistakes that cost him World War II. But the Germans made strange delays to their pursuit of the Allies on the micro level too. General Erwin Rommel, still months away from earning his sobriquet of the Desert Fox, commanded the 7th Panzer Division during the Battle of Dunkirk and was taken unawares by British resistance. They had few tanks, and few of those were equipped to hold up to the German artillery. The fact Rommel was surprised at all upset him, so he helped persuade Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt to divert the panzer divisions against Allied counterattacks rather than keeping steady toward Dunkirk.

On an even smaller scale, according to Julian Thompson's "Dunkirk: Retreat to Victory," the 6th Panzer division and the 29th Motorized Division had an opportunity to cut off the British 44th division, which had to go through or around the Germans to reach Dunkirk. Thompson calls their failure to do so "astonishing" and attributes it to German overconfidence. The 44th was largely reduced to traveling on foot, and the motorized division saw no need for haste in going after them. Poor coordination by the armored division also allowed the out-gunned British to inflict an unexpected amount of damage, a precursor to similar encounters against Rommel's forces in the desert and the Battle of Goodwood.

Allied miscommunication contributed to the myth that the French were abandoned

As the last of the Allies standing after the Battle of Dunkirk, it's understandable that the British press zeroed in on British valor. Coverage of Dunkirk often omitted the pivotal role French forces played in keeping the shores secure, and their contribution remains underappreciated to this day. But there is also a myth that the French were essentially abandoned by the British at Dunkirk. According to History, some 140,000 French soldiers were rescued during the evacuation, and at Winston Churchill's insistence, most of the French rearguard was rescued at the beginning of June 1940.

Part of the reason that the myth of French abandonment has endured is the poor communication between the Allies during the Battle of Dunkirk. Per The National Archives, British commanders assumed that as soon as retreat and escape became the game plan, they would be rescued by their ships and the French by theirs, but the French had not planned to evacuate. Even after French forces became pinned at Dunkirk, their navy was in the Mediterranean as part of a prior agreement with the British. And Lord Gort, who commanded the British forces at Dunkirk, was tactless and hostile to his Gallic partners.

Nevertheless, Britain was informally committed to helping as many French troops escape as it could. By the end of the evacuation, they were moving French and British troops in equal number. Many of the French, however, were to return to their country shortly thereafter, just in time for its final defeat by Nazi Germany.

The Nazis ignored intel that revealed British movements

The evacuation of Dunkirk took place over nine days, between May 26 and June 4, 1940. The German advance resumed on the first day of the evacuation, and by May 31, Field Marshal Georg von Küchler was getting intelligence on the movement of the Allies. Per Walter Lord's "The Miracle of Dunkirk," a number of suggestions based on the position of the Allies were relayed to Küchler by the Army High Command (OKH). One proposal was to take a number of German troops out to sea and land them behind the British. Another was to reposition German forces to give the Luftwaffe a clean shot at Dunkirk. Adolf Hitler himself, annoyed at the sandy beach's diluting effect on artillery shells, wanted them fitted with timers.

Küchler rejected every suggestion sent his way. He had already made his plans: A steady bombardment to wear down the Allies and then an all-out assault along the perimeter of Dunkirk on June 1. The fact that intelligence had intercepted communications that revealed the British were already on the move, had already moved from the east, and were vulnerable as they fell back, made no difference to him. He even got a break in the weather — several days of clouds and fog had scrambled planned Luftwaffe flights. And so his preparations continued without change, with no one at German headquarters expressing any misgivings that they were overlooking anything by sticking to the script.

There were British politicians who moved for peace during Dunkirk

At the same time that the British and French were trying to escape Dunkirk to fight another day, elements in the British government were prepared to let the battling end altogether. Making peace with Germany was an active discussion within the War Cabinet, despite Winston Churchill's refusal to consider it. Among those considering a negotiated peace was Edward Wood, better known to history as Lord Halifax. Halifax had seen Neville Chamberlain's efforts fall to pieces, and he wasn't sympathetic to the Nazis. But he was convinced that victory over them was impossible.

Per Foreign Policy, Halifax's preferred plan would have been to sue for peace while France was still in the war and Britain's air force was relatively unscathed. With some fight still left in the Allies, Halifax reasoned that Britain could secure terms that would safeguard most of the British Empire and let it carry on a stable, if not particularly happy, coexistence with Germany. He and Chamberlain still commanded considerable respect within the Conservative Party. Meanwhile, Churchill was faced with having to stand his ground against their ideas without wounding their pride to the point that they resigned and collapsed the government — all while the men of Dunkirk were being rescued.

Had Halifax prevailed, Britain would have explored peace options through Fascist Italy. But Churchill managed a one-two piece of internal diplomacy, soothing Halifax on May 27 while delivering his famous vow. "If this long island story of ours is to end at last, let it end only when each one of us lies choking in his own blood on the ground," he said.

There was a strange mismatch between the scale of defeat and the effect on British morale

When looking over the history of the Battle of Dunkirk, one incontrovertible fact hovers over the operation: It represented a massive defeat for the Allies. The blitzkrieg tactics of the Germans overran British and French forces within weeks. Thousands were killed. For all the men rescued, some 90,000 were left behind, as was nearly all the heavy artillery that the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) had brought with them. It was perhaps Britain's greatest military defeat, and Winston Churchill publicly acknowledged it as a "colossal military disaster" (per the BBC).

And yet, Dunkirk brought about a near-instant reversal of British morale. The mood in the United Kingdom, which was almost funereal when the evacuation began, turned euphoric by the time the BEF was returned. The shift was in part due to the realities of 1940s communication. A grim letter by King George VI suggesting bleak odds was published at the same time that the evacuation was picking up steam, making the survival and rescue of so many troops seem that much more of a miracle.

But the British press also leaned into the framing of Dunkirk as a miraculous feat — a divinely-guided victory snatched from the jaws of defeat. They played up the part of the "little ships," those civilian craft with crews that provided much-needed support but weren't nearly as decisive as the media claimed. Sober assessments of the scale of the loss went unheeded, even if they came from the prime minister. Britain needed the miraculous, heroic version to steel itself for what lay ahead.