US Presidents Who Made Huge Changes During Their Administrations

Because the United States is such a vital and influential global superpower, the elected head of the entire country wields tremendous power. Dubbed the most powerful person in the world, the president of the United States doesn't just lead the nation in a day-to-day capacity or take action when emergency strikes; they also get to interpret, tweak, and transform the law and operations of government as they see fit.

While U.S. presidents must still follow strict rules while in office, and the American government system is structured to prevent any one of the three branches from overstepping, some commanders in chief took some big swings with the powers to which the office entitled them. Many were responding to the needs or political climate of the time, while others acted from their hearts or agenda. At any rate, by pushing legislation, signing orders, or directing their associates and underlings to act on their behalf, a few presidents in particular reshaped American life with relative swiftness. Here are some of the best and worst presidents of the U.S. who managed to usher in monumental changes during their time in charge.

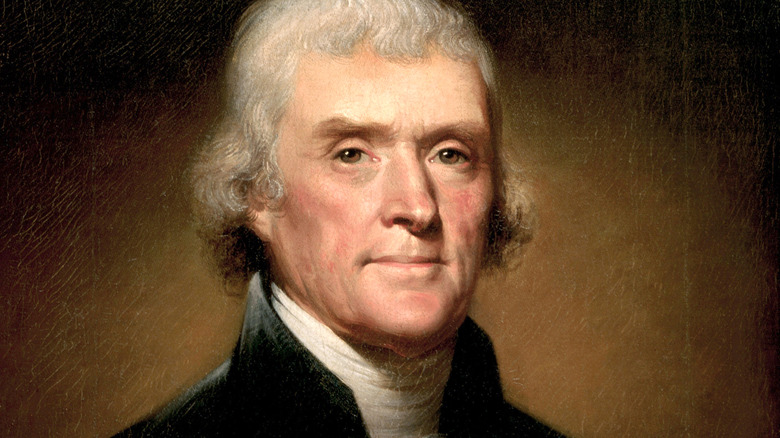

Thomas Jefferson doubled the size of the United States

When Thomas Jefferson ascended to the presidency in 1801, the U.S. comprised 16 eastern states, with the rest of the continent heavily contested. In 1795, the U.S. had signed a treaty granting access to the Spanish-controlled Mississippi River and ports of New Orleans, vital to the American economy. Napoleon wanted those lands, along with most of western North America, to return to France, having lost them at the end of the French and Indian War in 1762. Jefferson's fears of collusion between the two European nations were confirmed in 1802, when Spain decreed lands west of the Mississippi River back to France, blocking U.S. use of those important waterways.

Jefferson reacted on multiple fronts: Troops were sent to the Mississippi River Valley, while diplomat James Monroe and ambassador to France Robert Livingston were dispatched to broker some kind of deal with Napoleon, with the Americans being prepared to offer $10 million for New Orleans and Florida. In part because of a yellow fever epidemic running through Napoleon's troops in the Caribbean, and a fear of the American troops, Napoleon counter-offered: He'd sell all the land from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains, and from the Gulf of Mexico to the Canadian border. For $15 million, the Jefferson administration barred France and Spain from expanding its colonial presence in North America while also adding 827,000 square miles to the country. Instantly, the U.S. had doubled in area and the age of westward expansion had begun.

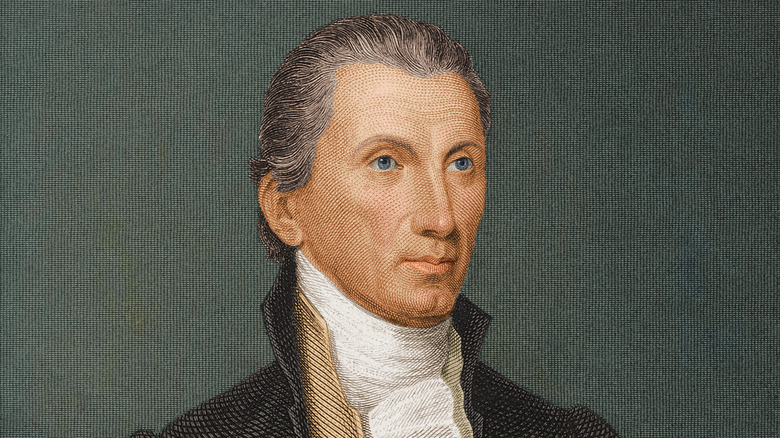

James Monroe ended European colonialism in the Americas

Previously serving as Secretary of State under President James Madison, James Monroe brought a keen understanding of his era's complicated world political climate when he became president in 1817. During his two terms, imperialist European nations experienced both setbacks and advancements in their dealings in the Western Hemisphere. Areas once controlled by Spain and France asserted their independence, while Russia claimed power over the West Coast of North America, moving in from Alaska. Fearing Spain, France, and Russia would attempt to reclaim old lands or create new territories, Monroe delivered a speech to Congress in 1823 that effectively declared the end of colonialism in the Americas.

Retroactively called the Monroe Doctrine, the president's speech proved foundational to U.S. foreign policy for generations while also establishing the still-young country as the local superpower of the West, and its self-appointed international police force. Monroe aimed to finish what the American Revolution had started 50 years earlier: to expel European powers from North and South America. It was also economically beneficial, too. The European style of mercantilism benefits only the economies of Europe. By establishing trading partners with other American countries, the local economies could thrive. In exchange, the U.S. offered protection of its neighbors from its former colonizers.

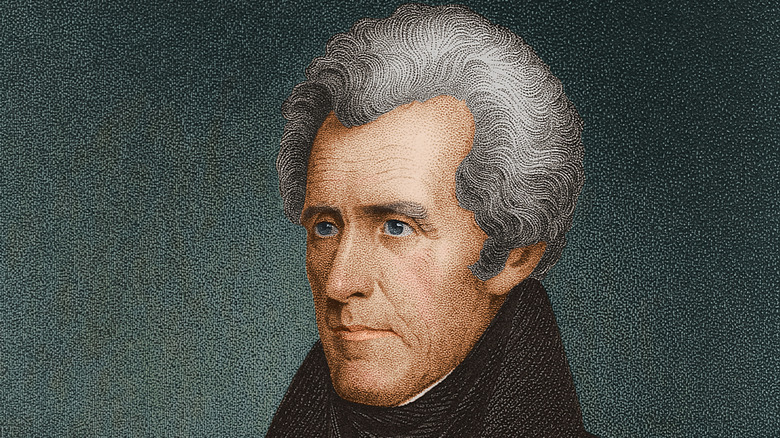

Andrew Jackson claimed control over occupied lands

Andrew Jackson's biggest and most overstated goal as president, which he talked about in his 1829 inaugural address, was to increase the size of the portion of North America controlled by the United States. The method by which he'd achieve that was brutal: to displace tens of thousands of Native Americans, annex their land, and create the legislation to make it all legal under U.S. law. In 1830, Jackson signed the Congressionally approved Indian Removal Act, which proclaimed authority over all lands occupied by Native Americans that fell between established U.S. states and the Mississippi River. At the time, the president called the Indian Removal Act the fulfillment of an idea set forth by Thomas Jefferson, who, when finalizing the Louisiana Purchase, suggested that some of those newly acquired lands could be set aside to relocate and cordon off Native Americans.

The mass evictions and expulsions began almost immediately. Starting in 1830, and continuing until 1850, indigenous people living in the region — stretching from what's now Michigan and down to Louisiana and Florida — were forcibly sent westward to the newly created Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) by U.S. military contingents. Of the 17,000 Cherokee marched out from their homelands during what became known as the Trail of Tears, 6,000 died. An additional 3,500 members of the Creek community died.

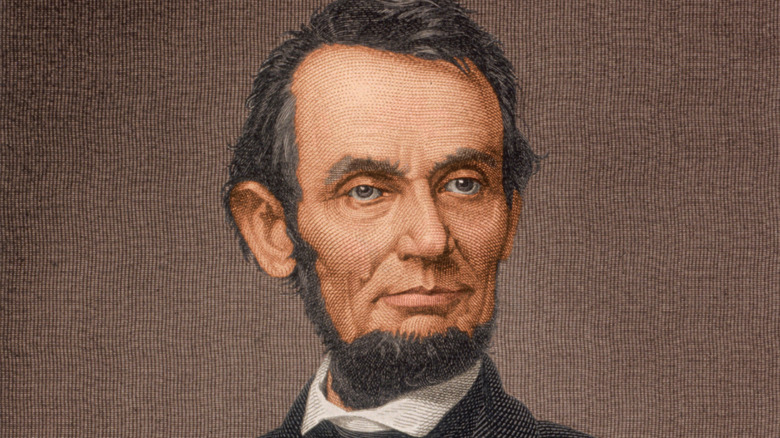

Abraham Lincoln ended slavery

Abraham Lincoln was elected president of the United States in 1860. The first victorious Republican candidate, he ran on his party's platform that insisted in part that enslavement, already abolished in many Northern states, shouldn't be practiced in newly acquired territories and admitted states. Six weeks after the election, South Carolina became the first of 11 Southern, pro-enslavement states to secede from the U.S., ultimately forming the Confederate States of America. As a result, in April 1861, the Civil War began, giving way to many messed-up events.

At first, Lincoln didn't send Union troops into battle to specifically fight against enslavement. His aim was primarily to keep the United States whole, and he treated the creation of the Confederacy as an action of rebellion that needed to be quashed. But in 1862, Lincoln explicitly and unequivocally made the Civil War a fight about enslavement versus abolition. Set to go into effect on January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, an executive order that sought to liberate enslaved people in certain American regions. Enslavement was declared illegal in four Union-aligned border states as well as in the Confederacy, where Lincoln's legal authority wasn't recognized.

The Union won the Civil War, and enslavement was eradicated nationwide. After Abraham Lincoln died, all the seceded states were readmitted to the Union and had to adhere to the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, which granted citizenship to freed enslaved people born or naturalized in the U.S.

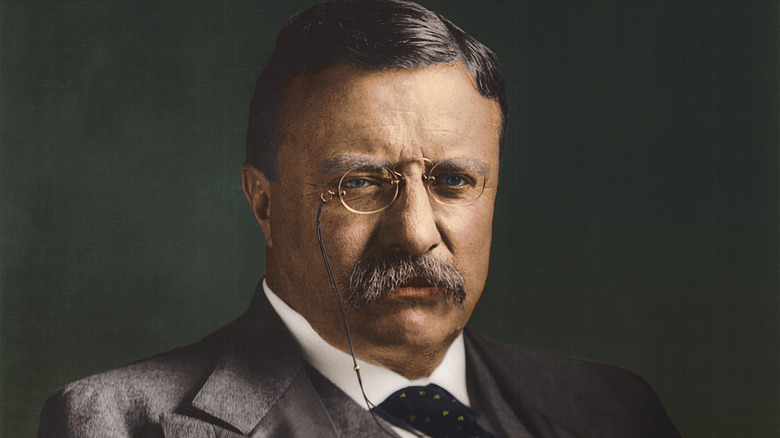

Teddy Roosevelt introduced regulation and safety across American life

Following the assassination of William McKinley in 1901, 43-year-old vice-president Teddy Roosevelt assumed the office. An agitator for conservation and politically a populist, Roosevelt enacted measures to preserve the natural features of the U.S., protecting them from exploitation by his chosen nemesis: big companies that operated with little to no regulation.

In October 1902, five months after 140,000 coal miners went on strike in Pennsylvania, Roosevelt personally brokered an agreement between the United Mine Workers and the mine operators. It was among the first moves in what Roosevelt would call the Square Deal, a system of laws and projects that Roosevelt believed would improve the quality of life for all Americans. Soon thereafter, he helped create the Department of Commerce and Labor in order to create some oversight of American business and industry, while also looking out for illegal trusts and monopolies. After he read "The Jungle," Upton Sinclair's exposé of appalling and unsanitary meatpacking industry secrets, Roosevelt pushed for the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Drug and Food Act, which called for federal inspection of food processing facilities and accurate food labeling.

Roosevelt was also an avid outdoorsman, and he acted on his philosophy of respecting nature throughout his presidency. He made Florida's Pelican Island the first federally protected bird sanctuary, established the National Forest Service, and with the National Monuments Act set aside 18 recognized natural wonders, including Muir Woods and Devils Tower.

Franklin D. Roosevelt put the U.S. back to work

Franklin Roosevelt was elected in 1932, during the Great Depression. The economy was in disarray, and to help alleviate all the suffering that went along with it, President Roosevelt spent his first 100 days in office trying to get the economy back on track, first by righting a flagging banking system and then putting unemployed Americans back to work. These actions were all a part of two separate editions of what the president called the New Deal. Within days of Roosevelt's inauguration, Congress had passed the Emergency Banking Act. After ordering all banks closed for four days, to prevent runs of customers withdrawing their savings from unstable institutions, Roosevelt's law made banks safe again by offering to bank them with the weight (and funding, if necessary) of the federal government.

The New Deal, both the first edition in 1933 and the Second New Deal in 1935, are notable for the public works projects they collectively introduced. The Tennessee Valley Authority provided jobs building dams along the Tennessee River, preventing flooding and creating cheap and plentiful hydroelectric power. The Works Progress Administration followed the same model, hiring thousands to build public structures like schools, highways, bridges, parks, and post offices, while the Civilian Conservation Corps needed workers to construct infrastructure in neglected rural areas. Through his New Deal programs, Roosevelt indirectly gave jobs to as many as 8.5 million people.

Harry Truman dropped the atomic bomb and rebuilt Europe

Inheriting the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1945 and with World War II still raging, former vice president Harry Truman acted quickly to end the conflict while simultaneously ushering in a new age of science, warfare, and political chess. Developed in secret by the Manhattan Project during Roosevelt's tenure, the world's first atomic bomb made its entrance as the most destructive weapon in human history, and on August 6, 1945, Truman put it to use. He authorized and ordered the bombing of the Japanese city of Hiroshima; three days later, another atomic bomb fell on Nagasaki.

With two population centers leveled instantly and 120,000 people dead, Japan unconditionally surrendered to the U.S. and its allies within weeks, marking the end of World War II in Asia. However, nuclear weaponry looked very attractive to the world's superpowers, and many nations would eventually develop and stockpile their own cache of atomic devices, leading to decades of Cold War between democratic and communist nations, a stalemate that threatened to devolve into Armageddon at any time.

Truman also helped Europe rebuild from its own wartime devastation, authorizing the Economic Recovery Act of 1948. Also known as the Marshall Plan after its creator, Secretary of State George Marshall, it allocated $13.3 billion to Europe to fight economic depression and famine. Not merely an act of goodwill, the project led to new economic alliances and created lucrative markets for American-made products.

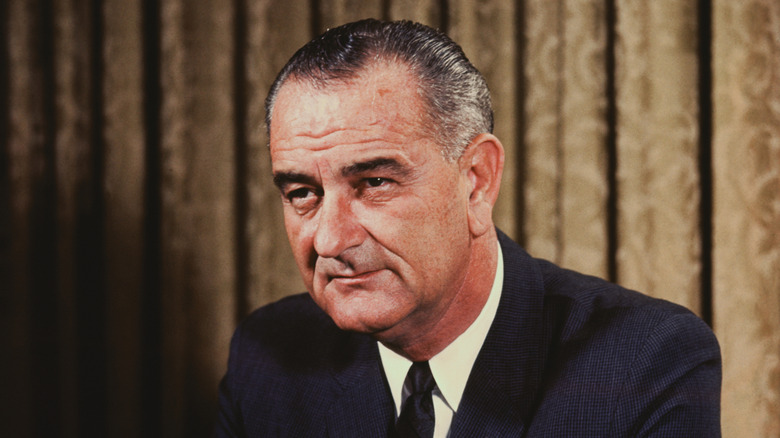

Lyndon Johnson created the social safety net

After the assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963, President Lyndon Johnson set about reviving and building upon his predecessor's agenda. Kennedy's New Frontier agenda became Johnson's Great Society, an expansive and assertive collection of progressive legislation designed to attack what the new president called the biggest social ills of 1960s American life: racism and poverty.

A former Senate majority leader skilled in negotiation and securing votes on bills, Johnson got Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act, which banned segregation by race and made racial and gender discrimination illegal in hiring practices. Johnson also championed the Voting Rights Act, which outlawed voter suppression tactics aimed at preventing Black Southern voters from casting their ballots.

As far as economic disparity was concerned, Johnson signed the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, thereby creating the Office of Economic Opportunity and the Job Corps, which oversaw numerous public welfare and aid programs and provided job training, respectively. Some of the organizations and programs brought to life included Head Start, or publicly-funded preschool, and Volunteers in Service to America, which sent volunteer teachers to underserved communities. And as the two primary populations lacking health insurance and care in the 1960s were older Americans and those living below the poverty line, Johnson helped create Medicare and Medicaid. Medicare paid for hospital and doctor visits for older Americans, while Medicaid covered medical expenses for those already in the welfare system.

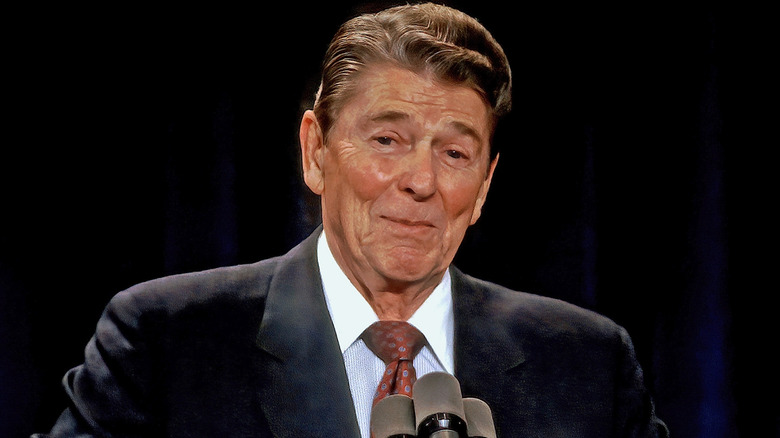

Ronald Reagan shifted the wealth to the top

After conservative research groups blamed the rampant inflation and slow economic growth of the 1970s on an abundance of workplace and environmental rules, the Republican party, under the leadership of 1980 presidential election winner Ronald Reagan, adopted a platform of aggressive deregulation. Early in his first term, Reagan and his administration attempted to eliminate entirely the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Department of Energy. Congress, controlled by the Democratic opposition, stopped the push, but the president was able to severely slash all those agencies' budgets nonetheless.

In other moves ostensibly designed to boost the economy, Reagan called for a revamped tax system that he felt punished large companies and the financial industry. He managed to pass the Economic Recovery Act through Congress in 1981, which trimmed taxes by 5% and 10% in successive years. Five years later, another Reagan-backed tax plan cut substantially dropped tax rates for the super-wealthy. The underlying principle behind those actions was the idea of "trickle-down economics," which proposed that cutting taxes to the individuals and companies at the top of the economy would theoretically open up more funds to stimulate job growth, and help the economy overall.

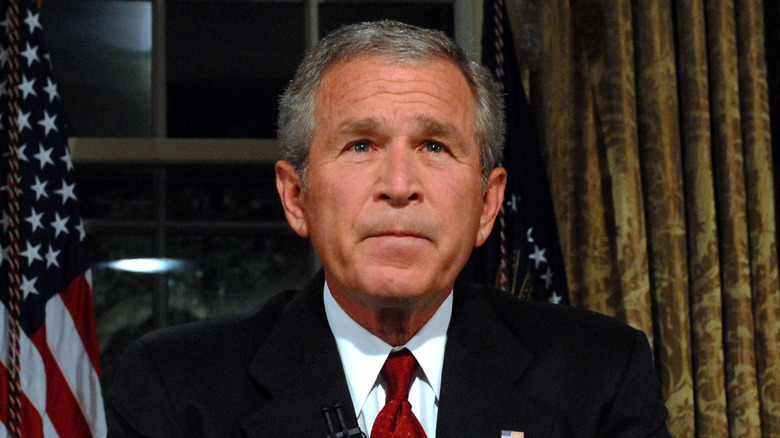

George W. Bush enhanced national security after 9/11

Two months after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, President George W. Bush approved the Aviation and Transportation Security Act. It created the federal-level Transportation Security Administration to carry out strict new practices to prevent future attacks on planes, including exhaustive baggage checks, enhanced passenger screening, and growth of the air marshal program. Another way President Bush responded to the events of 9/11 was with the creation of the Homeland Security Council. Established via an executive order, the organization would be elevated to a cabinet-level position as the Department of Homeland Security in 2003, bringing all domestic security and anti-terrorist activities under the umbrella of one organization.

President Bush's primary and most far-reaching post-9/11 legislation was the creation — and steady expansion of – the USA PATRIOT ACT, which granted federal entities the authority to act aggressively in the name of anti-terrorism. According to the U.S. Treasury Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, agencies acting at home and abroad were empowered "to prevent, detect and prosecute international money laundering and financing of terrorism," among other stipulations.

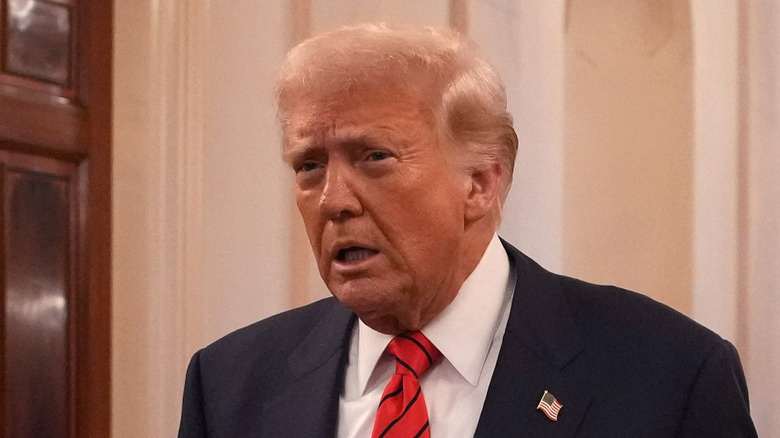

Donald Trump aggressively pursued immigration issues

During the first days of his second, non-consecutive presidential term in 2025, Donald Trump signed more than 80 executive orders that sought to force immediate change in almost every department of the federal government. Nine of those executive orders concerned immigration, migration, and citizenship issues, with President Trump attempting to quickly make good on campaign promises to better secure the nation's borders to prevent illegal entry and to deport individuals already in the country who arrived in an allegedly unlawful manner.

In one order, the President declared the Mexican border situation a national emergency, and authorized military deployment to prevent immigration, particularly by criminal means. Other executive orders halted the Refugee Admissions Program entirely and indefinitely, banning those seeking asylum from coming to the U.S., and directed the expansion of a Migrant Operations Center at the Guantanamo Bay federal detention site to imprison and process for deportation any illegal aliens accused of crimes.