How Archeologists Unearthed Million-Year-Old Weapons In An Ancient Lakebed

Humanity may have mapped the entire world as early as the 16th century, but as a recent archaeological study in Iraq has confirmed, there are still worlds to discover if you know where to look. Toward the tail end of 2024, archeologist Ella Egberts, a researcher at Vrije University Brussel in Belgium, undertook a pilot project to the Iraqi Western Desert alongside three archeology students from Iraq in search of Stone Age artifacts that would "help gain insight into the geomorphological history," according to a Vrije University Brussel statement.

What the team discovered during their time in Iraq has made headlines in archeology publications, with Egberts branding the fieldwork a "huge success." Analysis has shown several of the found objects may be over a million years old, dating back to the dawn of our earliest ancestors.

What is even more remarkable about these finds is that the team in question used no special equipment to uncover them. Whereas many archeological projects are dig sites, requiring heavy machinery to uncover artifacts hidden beneath the earth, each object discovered during Egberts' pilot project was simply lying out in the open, ready to be picked up.

A major archeological haul

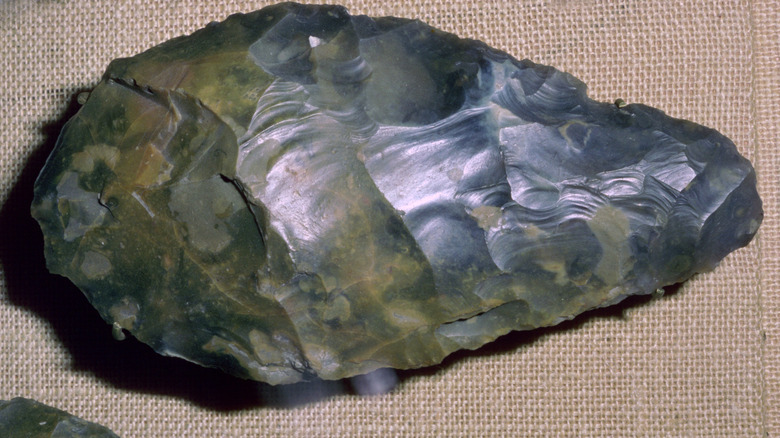

Elle Egberts' team collected over 850 artifacts from a single site in the Al-Shabakah area of the Iraqi Western Desert in November and December 2024. Among the headline-making finds were two Lower Paleolithic hand axes, which to the eye, look like teardrop-shaped stones coarsely shaped to have a point and cutting edge. Egberts believes these objects may date from 1.5 million years ago. Their creation came before the arrival of homo sapiens (the genus of modern humans) and the date to the time of homo erectus, a human species that went extinct over 100,000 years ago. For context, the oldest tools ever discovered date back 3.3 million years. Other artifacts found during Egberts' fieldwork uncovered numerous Levallois flakes, a more sophisticated cutting tool that may have been crafted 300,000 years ago.

Archeologists find it remarkable that such ancient artifacts are simply lying out in the open in the Iraqi Western Desert, just waiting to be picked up, although to the untrained eye, such precious finds may simply resemble sharp rocks. Egberts has reported that her team's fieldwork was carried out without a hitch, despite the impression in the West that Iraq continues to be a dangerous country to visit. "Apart from the presence of numerous checkpoints, we were able to carry out our work without any problems," said Egberts, per a Vrije University Brussel statement. "The people are friendly, and it's actually very nice to work in Iraq. Initially, earlier last year, we did have to postpone our expedition due to a security warning. That was probably related to the war in Gaza..."

There is much more to be uncovered

As the statement from Vrije University Brussel reported on January 29, 2025, Elle Egberts' project in the Iraqi Western Desert is far from over. The findings already made public were just from a single Paleolithic site: the team has identified six more, all within the same 12-mile by 6-mile area.

The area of desert in which the discoveries were made was once a vast lake, with the team exploring the remains of what were once riverbeds to uncover the objects left unstudied for millennia. The project will continue with further expeditions to the area, and Egbert and her team intend to return to the sites they have already identified in search of more treasures. "The other sites also deserve equally thorough systematic investigation, which will undoubtedly yield similar quantities of lithic material," Egberts claims.

Ready to dip into the past again? Here are some incredible archaeological finds that changed everything.