What Your History Class Didn't Teach You About WWII

If you attended high school in the United States, then it's all but inevitable that you've come across a unit or lesson plan concerning World War II. That makes sense, of course. The Second World War was truly massive, with an estimated 100 million soldiers deployed across the globe and, depending on your source, a grim death toll of around 60 million (the majority were civilian casualties). Many of the survivors were displaced by the conflict, while it dramatically reshaped seemingly everything from individuals to small communities, to geopolitical relations between superpowers.

Speaking of superpowers, the story of World War II — condensed by the length of a school year and all the other subjects your poor history teacher had to cover — is often reduced to broad strokes and major players. There were the Axis Powers, widely summed up as Germany, Japan, and Italy. Then there were the Allies, headed up by the Big Three of the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union. But who has been left out of that story and which tales ought to be told more? As it turns out, there are many things your history class simply didn't teach you about this globe-spanning war.

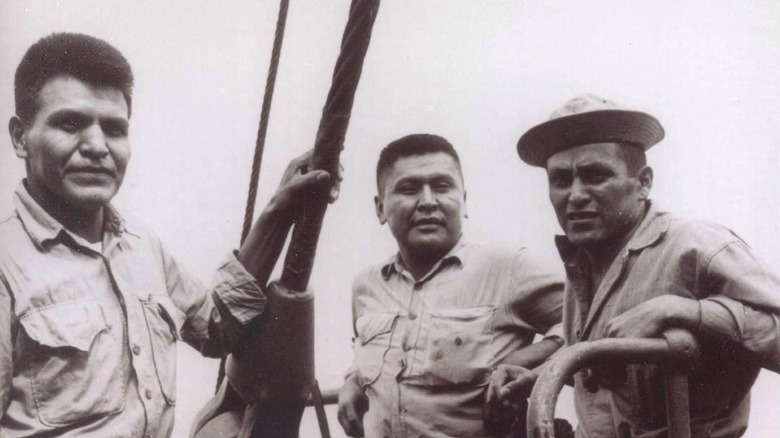

Indigenous languages stymied Japanese codebreakers

Perhaps, at some point in class, you learned about the importance of coded communications during the war. It makes sense — why send vital messages about troop movements or invasion plans without some level of security? It was a common practice on all sides, as was the attempt to break these coded messages. But while some efforts were successful, other codes were never broken thanks to the linguistic contributions of Indigenous Americans.

Often referred to as the Code Talkers, U.S. service members who were also Native used their fluency in indigenous languages to set up codes that Japanese listeners simply couldn't break. The history of U.S. Code Talkers actually goes back to World War I, when the Choctaw Telephone Squad began operating in Europe. By WWII, the U.S. military was specifically recruiting people who fluently spoke both a tribal language and English. Their job was to translate coded messages from English into their language, then communicate that message (often via radio) to another tribal language speaker. The contents were crucial to military operations, including information about their own troops and the movements of the enemy.

Many of these Code Talkers were Diné (or Navajo) people. They were expected to completely memorize a complex code and whose work was credited with helping the Marines win the otherwise pretty difficult Battle of Iwo Jima (among many other achievements). Other Code Talkers hailed from a diverse array of tribes including the Comanche, Hopi, Mohawk, Chippewa, and Crow.

The Allies had an entire Ghost Army

Naturally, a lesson on World War II is going to include information on dates and troop movements, but what about propaganda and disinformation? For the Allies, one of the most powerful such campaigns was the spooky-sounding Ghost Army. As far as anyone call tell, no actual spirits were involved, but the WWII Ghost Army did include the phantom-like impression of many troops and much military equipment.

If German forces had looked more closely, they could have seen that a lot of that equipment was fake. These included inflatable tanks, fake radio transmissions, and speakers blasting sound effects. The effort was undertaken by about 1,100 artists and military members who put on a traveling show of sorts to fool Nazi Germany. They kept Axis military forces confused and often going in the wrong direction, including their part in the March 1945's Operation Viersen.

While a real detachment of soldiers was preparing to cross the Rhine, a Ghost Army 10 miles away set up hundreds of dummies and fake equipment to convince anyone listening that the divisions were actually elsewhere. Radio transmissions, blasting sounds of bridge construction, and loud discussions of their fake plans in local spots completed the picture. Ultimately, Nazis attacked the false army while the real one crossed the river in relative peace. Their efforts during the war saved an estimated 15,000 to 30,000 members of the U.S. military.

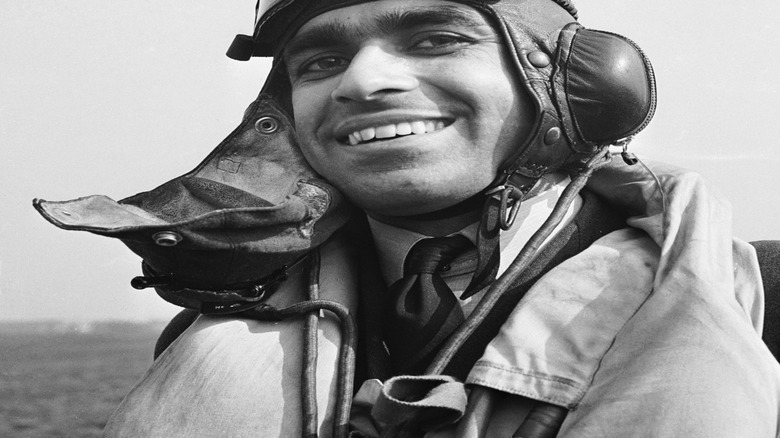

Night Witches struck fear into the hearts of German soldiers

How did we miss out on learning about the Night Witches? Called "Nachthexen" by German soldiers, these daring all-female Soviet pilots dropped over 23,000 tons of bombs on the Nazis. The group was formed by already-famous navigator and lesser-known WWII heroine Marina Raskova, who got permission to form a group of attack aviators as Germany landed major blows against the Soviet Union. And while the old-school biplanes were the result of a scanty budget allocated to the women (not to mention widespread skepticism and harassment), the old aircraft gave them an advantage.

The small planes rarely showed up on radar or other monitoring equipment, while the ability to cut engines just before attack allowed them to quietly glide and surprise the enemy. The old aircraft could also fly more slowly than their Nazi counterparts, which stalled out at lower speeds. Because they were also denied radio equipment (along with a lack of parachutes, guns, or up-to-date navigation tools), there was no radio communication to intercept.

Their skill led some Germans to suspect they had been given medication that somehow allowed them to see in the dark. But the reality is that the Night Witches — many of whom wanted revenge for attacks against their families and homes — were highly skilled and motivated. Raskova herself died in action in 1943, joining the 30 pilots lost in the program. All told, the Night Witches flew over 30,000 missions.

Churchill considered attacking the Soviets

Any astute student can figure out that the alliance of the Allies was pretty tenuous, especially when it came to the Soviets. Of course, military leaders couldn't say that outright, especially when Soviet troops had taken over Berlin by May 1945. But United Kingdom Prime Minister Winston Churchill and members of his government were uneasy. They were so concerned about the increasingly powerful Soviets and their Communist puppet regimes that British strategists came up with a plan ominously deemed Operation Unthinkable.

Churchill had tried to get U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt in on the idea, but FDR wasn't interested. His successor, Harry Truman, was more into it, but never fully came on board. And while the war with Japan was still ongoing, Soviet help could be vital ... or, if sufficiently motivated by bellicose Allies, Stalin could link the well-supplied USSR with Japan.

So, Operation Unthinkable came to be, at least conceptually. But when the Joint Chiefs of Staff and other officials really looked into the idea, they came away chastened. The Soviets simply had greater numbers, more territory, and had demonstrated the ability to stick it out through prolonged war. Even as Poland fell under Communist control, enacting Operation Unthinkable was deemed, well, unthinkable. Instead, the world entered into a postwar period marked by uneasy compromises and anxiety-inducing rivalries — hardly the stuff of easy lessons or straightforward test questions. The plan was shuttered and kept so secret it didn't become public knowledge until 1998.

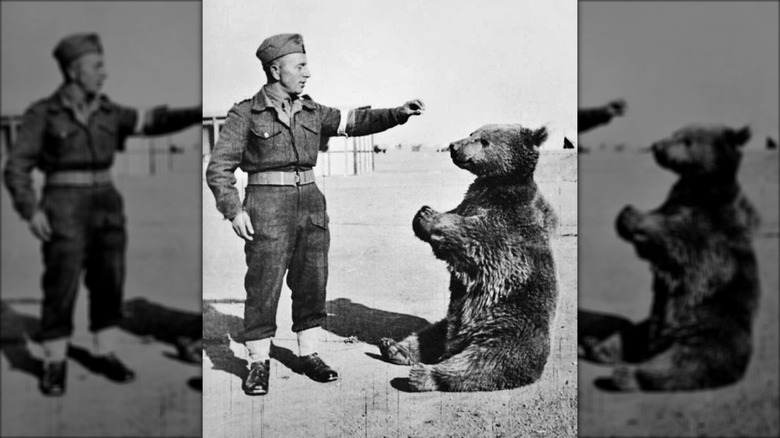

The Polish military had a pet bear with rank

The story of Wojtek starts not in the European or Asian theatres of WWII, but in the Middle East. Of course, the Second World War affected just about every part of the globe, which was why Polish troops were sent to Iran to fight the Nazis. There, members of the 22nd Artillery Supply Company of the II Corps traded with a local shepherd for an orphaned brown bear cub. The company named the bear Wojtek (a shortened version of "Wojciech," Polish for "joyful warrior") and eventually gave him the rank of private. His handler, Peter Prendys, also taught the bear the basics of company life like saluting and marching. Beloved by his fellow soldiers, Wojtek got treats like dates, beer, and cigarettes (which he reportedly ate instead of smoking). However, others in the company later noted that luxuries like beer were rare, and Wojtek was more likely to get plain water instead. Wojtek also enjoyed wrestling with some of the soldiers.

Wojtek soon became a favorite of the company, perhaps because soldiers displaced by the war empathized with the young, orphaned bear who also found himself far from home. And though Wojtek learned to carry shells during battle, he survived and went to live in Scotland, dying in the Edinburgh Zoo in 1963. Today, there remains a statue of Wojtek alongside a fellow soldier in Edinburgh's Princes Street Gardens.

Britain planned for a secret cave bunker on Gibraltar

Britain does have an outpost on Gibraltar, the very southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, poised between Spain and the Mediterranean Sea. But, during the war, it was vulnerable. With Axis forces nearby in Northern Africa and to the east on the island of Sicily, the specter of a German or Italian takeover wasn't all that far-fetched.

In case of such a situation, British forces had a plan, but it was potentially grim. Known as Operation Tracer, a small group of men were to be left behind in an underground bunker excavated in great secrecy. At first, the plan was for five people to stay for only a year in what became known as the Stay Behind Cave complex. Eventually, that was expanded to a maximum of six people for up to seven years. They were to be trained not only in surveillance techniques but also in how to maintain their quarters, eat properly, and stay psychologically healthy over an agonizingly long stay. If anyone died, they were to be buried in the floor of the cave.

Though construction was completed by 1942 and a team was put together, the invasion of Sicily in August 1943 helped turn Axis attention away from Gibraltar. It was soon sealed up, and though rumors persisted of a secret WWII cave in the area, no one was sure they had uncovered the Stay Behind Cave until the late 1990s.

Germany wasted tremendous time searching for rats full of bombs

World War II is full of rather wild weapons innovation attempts, from space-based efforts to tiny bombs strapped to bats. Yet few were as gross — and, in its own odd way, as fairly effective — as the rat bomb. The basic idea was pretty much as it sounds. British forces came up with the idea of planting charges inside dead rats. These were to be left beside German coal supplies, with the idea that someone would see a dead rat and hastily shovel it into a boiler alongside the coal to get rid of the nasty thing. The charge would quickly explode and ruin the boiler, thus hampering the Nazi war effort.

At first, the whole thing seemed to be a dud, as the Germans figured out the ruse right away. But while the Allies soon gave up on the idea of explosive rats, German soldiers seemed fairly spooked by the idea and spent considerable time combing through their coal looking for rat bombs. Ultimately, though Britain put little additional effort into the incendiary rodents, it remained an oddly effective time-waster and decidedly gross dent in enemy morale.

The Nazis toyed with the idea of a huge space mirror

It sounds like the plot of an especially far-fetched James Bond adventure, but the notion of a giant, weaponized space mirror launched by Nazis was — for at least a brief time — a real possibility. As revealed by the end of the war in Europe by summer 1945, German scientists were busy at work on all sorts of weapons that some hoped would turn the tide of war back into their favor. Of course, that did not work, and Allied intelligence officials were left to learn just what the enemy had been up to. This included what came to be known as a sun gun, a massive parabolic mirror that would have been launched into space. With the right positioning, it could have focused the sun's rays onto one spot, blasting key targets.

Ultimately, the idea literally was never going to take off, especially as Germany was hit hard by advancing Allies. Rockets weren't powerful enough for space station-building purposes, the right sort of mirror was hard to make, and it wasn't clear how it would all be maintained. Even so, the sun gun concept persisted for some time, both as part of the quasi-legendary, sometimes off-the-wall Wunderwaffen (wonder weapons) developed by Germany and as more altruistic scientific ideas. A very similar concept was even floated as a way to concentrate heat onto the surface of Mars and create small pockets of Earth-like conditions in a far-future situation.

One battle saw American and German soldiers working together

For the vast majority of World War II, German and American soldiers were on opposite sides of the conflict. Yet there was an odd one-off situation when these two groups teamed up to fight against what they had deemed to be an even greater enemy. It all starts with Castle Itter, a medieval Austrian fortress that had been repurposed as a prison for high-ranking detainees, including French government officials, military officers, and a famous tennis player. Though they had far more comfortable conditions than those detained at concentration camps, the prisoners of Castle Itter were nonetheless prisoners. And, as Germany started to fail by 1945, the possibility that they would all be killed by retreating Nazis became all too real.

Eventually, however, there came Major Josef Sepp Gangl, once a vaunted Wehrmacht officer who had soured on the Nazi regime and wanted to defend the Itter prisoners. He and his small group of soldiers teamed up with U.S. tank commander Captain Jack C. Lee Jr. A Sherman tank containing a likewise small group of American soldiers under Lee's command made it to the castle. But they were followed close behind by the Waffen-SS, who managed to destroy the U.S. tank but couldn't breach the castle itself. Lee and Gangl's combined groups managed to successfully defend Castle Itter, saving the lives of the prisoners inside with only one death — Gangl himself, who was struck by a sniper's bullet.

Colonial troops are often forgotten

When talking about the Allies of WWII, the so-called Big Three are often mentioned: Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and the United States. But while this trio of nations did put considerable effort into defeating the Axis powers, they were not the only ones involved in the fight. Across the globe, people from what were then colonies of Britain also served, and in fact had been serving in multiple wars over the years. Divisions of Indian soldiers were stationed in North Africa, Italy, Greece, and Java, among many other places. Of an estimated 2.5 million troops, more than 36,000 Indians were estimated to have been killed or missing in action during the war. Many more were part of the overall war effort as India provided vital supplies and served as a strategic military base of operation.

But where are the monuments and lesson plans dedicated to these soldiers? Commemoration of their work is pretty scattered and has been marred by colonialist attitudes that treated them as lesser-class citizens. For instance, many commanding officers of these companies were European or American, regardless of how skilled or decorated the people ranked beneath them were. They were also paid less and weren't necessarily consulted when the British Empire wanted to pull resources from colonies into the conflict. Still, this widespread participation empowered many independence movements, as when Indian independence activists including Gandhi began agitating for separation (though Gandhi and others had begun organizing for independence decades earlier).

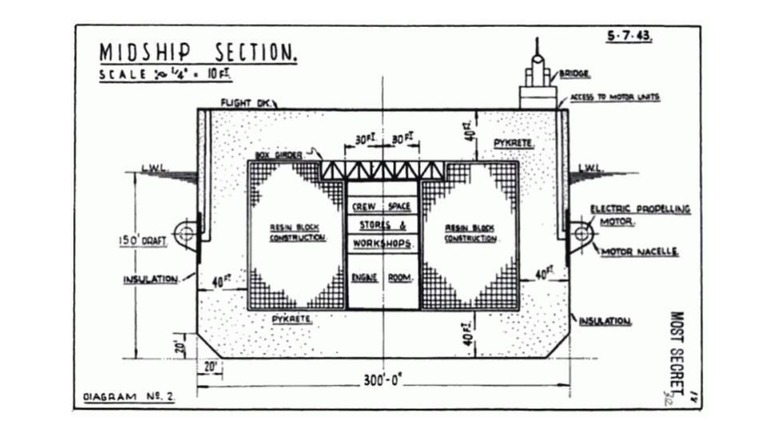

Britain tried to build an aircraft carrier out of ice

If you worry that standing in front of a classroom and droning about supply lines is sure to generate snores, it's time to talk Project Habakkuk. Named after a Biblical reference, the project began in 1942, when scientist Geoffrey Pyke was trying to address the problem of moving through the north Atlantic. Nazi U-boats dominated part of the region, as military planes had a difficult time getting out far enough. What's more, key shipbuilding materials like steel were getting scarce. So, how were ships to make it through the infested waters safely? Pyke's solution: Get a whole bunch of ice.

It sounds like a made-up military experiment, but it was the real deal. Ice was considered a particularly tough material, as attempts to smash icebergs had already demonstrated. Pyke designed a ship with an ice hull (later iterations used an ice-wood pulp mix, called "pykrete" in Pyke's honor). It would have been the then-biggest warship, at about 2,000 feet long and over 2 million tons. Britain went so far as to source ice from Alberta, Canada, building a 60-foot prototype there in 1943. But though it floated, crafting a seaworthy vessel remained tricky.

Then, Iceland came into play as a key base in the north Atlantic, while radar advancements made it easier to strike back against U-boats. By summer 1943, testing was called off and the Project Habakkuk prototype was allowed to sink into Jasper National Park's Patricia Lake.