The Life And Tragic Death Of Jesse James

Most everybody has heard of Jesse James — the legendary outlaw who robbed and murdered his way across the Midwest. The man is a legend in his own right, and James' rise to fame began while he was still alive.

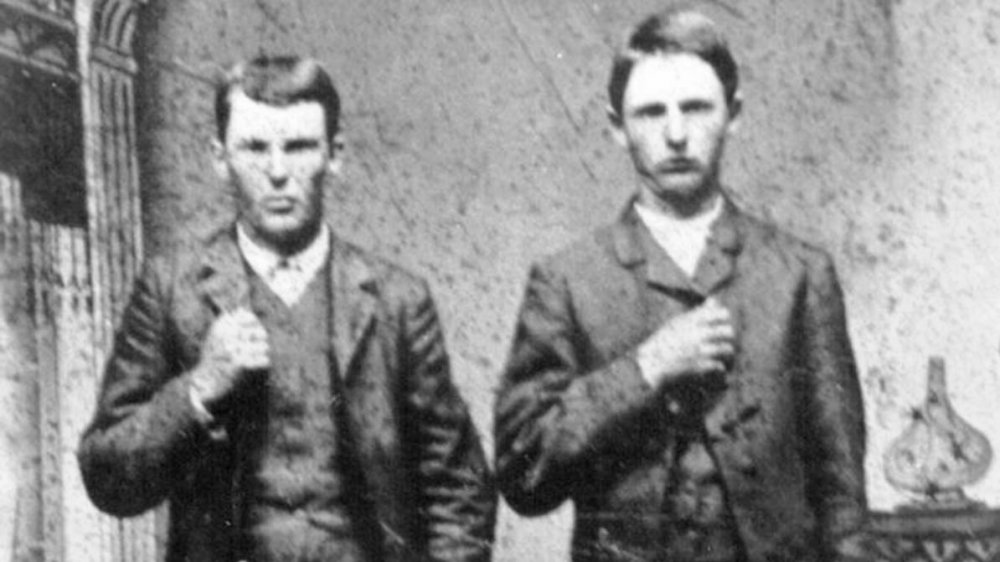

After serving as a Confederate soldier in the Civil War — perhaps as revenge against Union soldiers who attacked his family farm in 1863 — James actively pursued the life of an outlaw. Frontier America, egged on by the paparazzi of the day, would revere the fierce young man who carried a chip on his shoulder and rebelled against society at large. Those looking for a hero found one in James, who relentlessly robbed trains and banks while maintaining the demeanor of a well-dressed, charming Dapper Dan and family man. With his brothers, half-brothers, and others, James plowed through the Midwest, guns a-blazing, and committed more than 20 robberies between 1860 and 1882. His take was an estimated $200,000, nearly all of it gained along a trail of blood.

But while many people think that he robbed from the rich and gave to the poor, HistoryNet classifies this widespread belief as "purely fiction." And there's plenty more you probably don't know about the life and tragic death of Jesse James.

The making of an outlaw

The man who would become a fearsome outlaw started out a baby like everyone else. He was born Jesse Woodson James to the Reverend Robert James, a Baptist minister and successful farmer, and Zerelda Cole James in Kearney, Missouri on September 5, 1847.

According to History, Robert died in the fall or winter of 1850, on a trip to preach in the goldfields of California. A widow at the age of 28 with three children to feed — 10-year-old Frank, 4-year-old Jesse, and infant Susan — Zerelda knew that finding another husband was key to her survival. Missouri marriage records show her second marriage to Benjamin Simms in 1852. The marriage wasn't a happy one, and Simms died just two years later. Zerelda probably hoped the third time was a charm when she married Reuben Samuel in 1855.

The world of the James children was rocked by their father's death, their mother's poverty, and her subsequent marriages. Things only got more complicated when, in 1863, a group of Union militiamen converged on the family farm. They were looking for Frank, who was a member of a Confederate guerrilla gang commonly known as "bushwhackers," and engaged in attacking Union sympathizers as the Civil War raged. Young Jesse was ambushed and whipped by militia soldiers, and Reuben Samuel was hanged from a tree and tortured. Samuel survived, but Jesse became determined to join his brother and fight for the South.

Jesse James and the Civil War

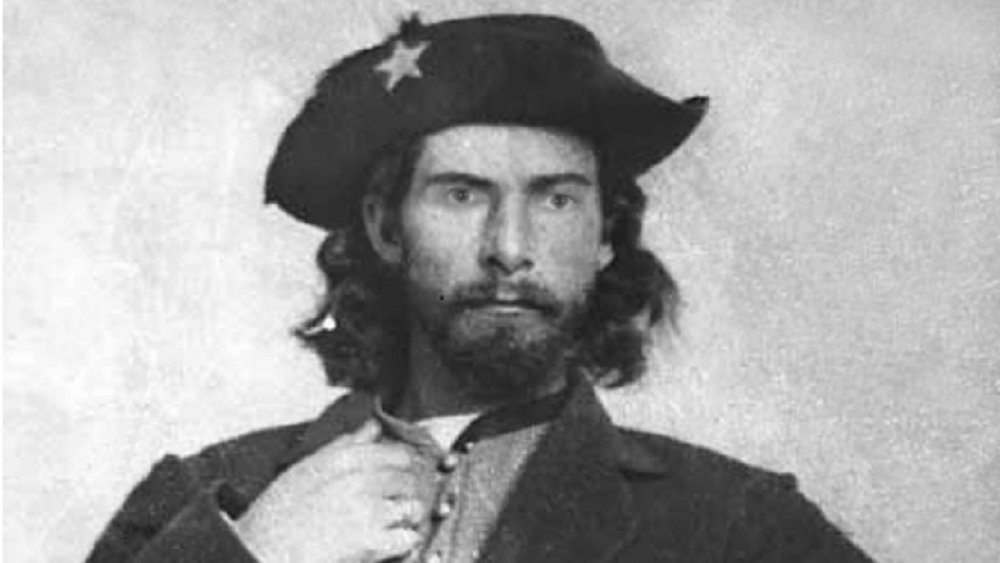

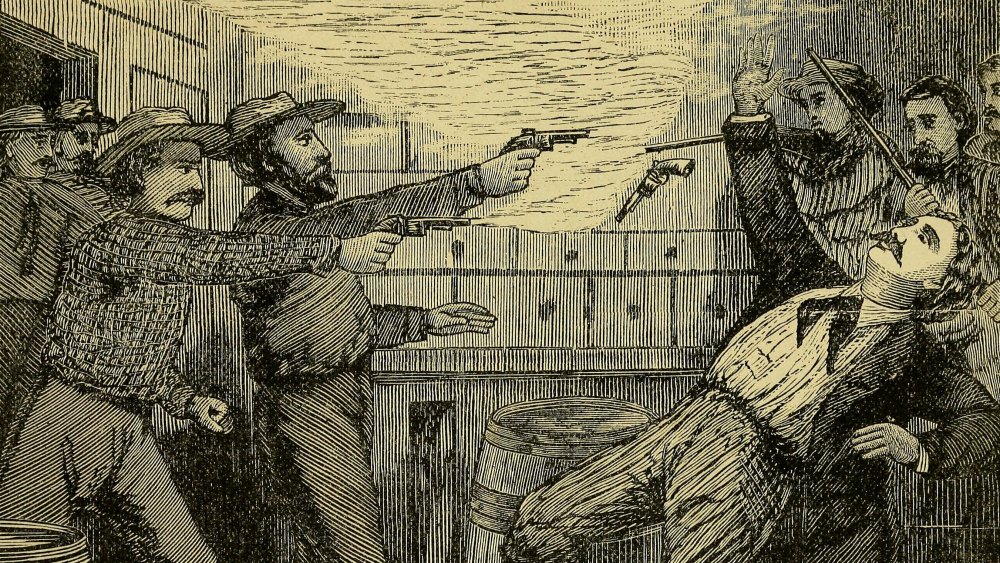

Soon after the attack on the family farm, Jesse James joined the war. The National Park Service's documentation of the Civil War confirms that Jesse signed up with the Confederate 4th Regiment of the Missouri Infantry. Within a year he had joined his brother Frank, whose guerrilla gang was headed by William "Bloody Bill" Anderson (pictured).

In September of 1864, the notorious group robbed a Union congressman, James S. Collins, before raiding a Union passenger train. On board were 22 furloughed soldiers who had surrendered, according to History. Anderson's gang ordered the men from the train, and mercilessly murdered each of them. The Union 39th Missouri Volunteer Infantry set out in pursuit of Anderson's gang, but was ambushed at Centralia, Missouri by the guerrillas. Anderson's men killed over 100 soldiers. The bodies of the dead were mutilated, while the survivors were brutally tortured. The battle, in which both Frank and Jesse participated, was later called the Centralia Massacre. Jesse was only 16-years-old.

In May of 1865, Jesse was outside of Lexington, Missouri when he was shot in the chest. His cousin, Zerelda Mimm (who was named after Jesse's mother), nursed him back to health. But the atrocities Jesse and Frank committed during the war were considered so terrible that the family had to leave Clay County.

Jesse James was the Robin Hood of the West — not

James' experiences during the Civil War would result in some post-traumatic stress disorder of the worst kind. Unable to return to a normal life, the young man turned to a life of crime instead. According to History, James' first widely-publicized bank robbery occurred in 1869, and went terribly wrong.

The robbery took place in Gallatin, Missouri, where James thought he recognized the cashier as Samuel Cox — the man who had managed to kill James' army buddy Bloody Bill Anderson in 1864. So James shot him to death. But the cashier was not Cox, rendering his killing even more senseless and brutal. Worse yet, the bounty James snatched up on his way out the door turned out to be a portfolio of bank stationery, not money.

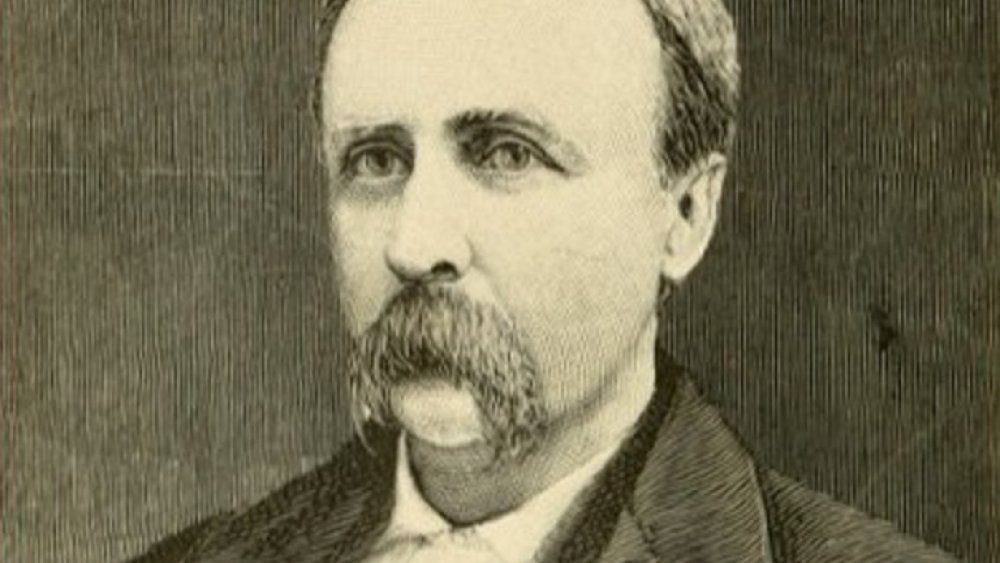

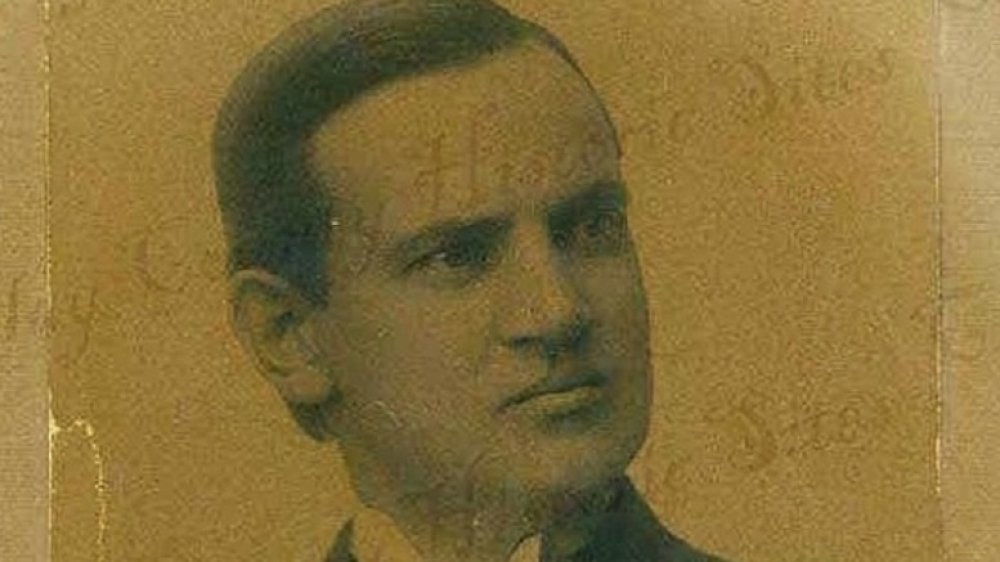

As news of James' activities went public, pro-Confederate newspaper editor John Newman Edwards (pictured) decided to spice up his own paper with sensational stories about the murderer and would-be bank robber. Edwards published articles portraying Jesse James as a hero who used his ill-gotten gains to help the poor, while James himself penned letters to the editor defending himself. Readers got their dime-novel fodder, while Edwards used the stories to inspire his fellow Confederates to regain political power. America bought the story, although no evidence has ever been uncovered to substantiate Edwards' claims that James was a 19th century Robin Hood.

More robberies, a marriage, and a raid

Jesse James would commit more robberies over time. According to PBS, by June of 1871 he had hooked up with the notorious Younger Brothers gang and robbed another bank in Croydon, Iowa. James discovered that most of the locals were attending a speech by orator Henry Clay Dean at the Methodist Church. After swiping $6,000 from the bank, the gang busted into the church and angrily "shook the stolen money at the crowd."

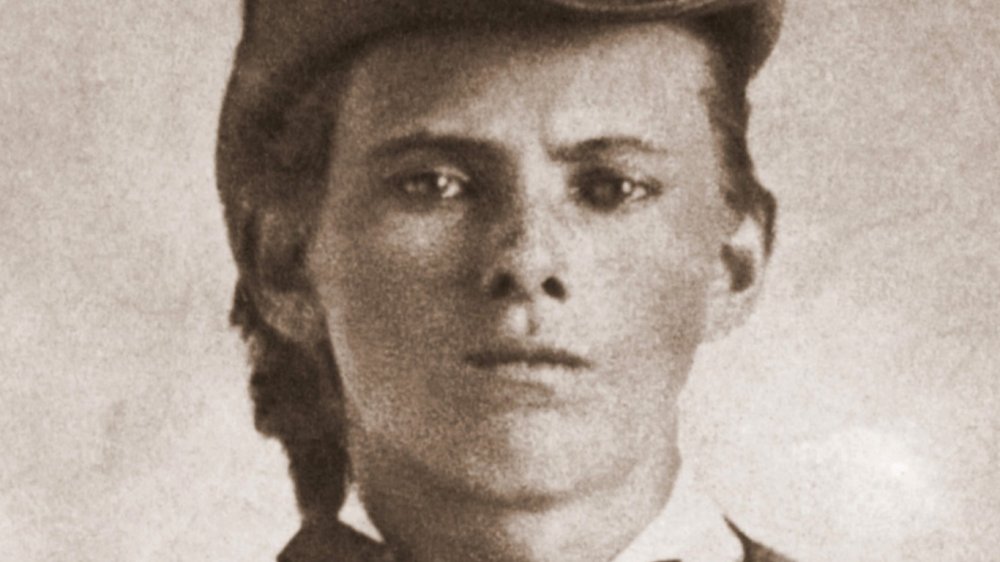

James also started robbing trains and leaving his own press releases at the crime scenes. Many of James' robberies turned violent: At another bank holdup in Kentucky during 1872, the unarmed cashier was shot but refused to open the vault even as he was dying. A more successful robbery, a train at Gads Hill, Missouri, took place in 1874. (In between rampages, Jesse managed to marry Zerelda "Zee" Mimms (pictured), the cousin who took care of him after he was shot in 1865. Missouri marriage records show the couple was united in matrimony on April 24, 1874, three months after the Gads Hill Robbery.)

After the train robbery, Pinkerton's National Detective Agency was brought in. According to History, agents snuck up to Zerelda and Reuben Samuel's farm in the dead of night on January 25, 1875 and tossed a bomb into the house. In the resulting explosion James' 8-year-old half brother was killed, and his mother lost her arm. Worse yet, the James boys were nowhere near the farm.

A child and a request for peace

In March of 1875, a sympathetic group of citizens rallied for an amnesty bill to release the James brothers from all guilt. According to Jesse James and the Movies, the bill made it to the General Assembly, where 58 legislators voted for it and only 39 voted against it. But the tally failed to meet the two thirds majority vote necessary for the bill to pass.

James, who had fled with his family to Tennessee, continued pushing for amnesty. He was likely inspired by the impending birth of his first child, Jesse Edwards James (pictured). Just before the baby was born, James wrote a letter to the New York Times which was reprinted by other newspapers, including the August 5 issue of the Leavenworth Weekly Times in Kansas. In his letter, James expressed his opinion that it was "high time that this cruel war was over." He now claimed he was a "high-toned gentleman" who was being "persecuted for the sake of the confederacy." What really incensed him, he said, was that he was being "reproached with horse-stealing and burglary by Democratic and Southern newspapers," for whom he fought in Civil War. But the Times concluded that "an application for 'amnesty' does not really affect the main facts charged against the criminal."

James had no choice but to remain an outlaw, and set about acting like it. Meanwhile, according to census records, Zee gave birth to Jesse Jr. in August.

Jesse James' failed bank robbery in Minnesota

A year after his plea for amnesty, Jesse's wife gave birth to a second child, identified by census records as Ethel Louise James. According to History, just a month later, on September 7, 1876, the James-Younger gang — consisting of Frank and Jesse James, Cole, Jim, and Robert Younger, and three other gang members, waltzed up to the First National Bank in Northfield, Minnesota. The men had heard that noted Union general and Republican governor of Reconstruction-era Mississippi, Adelbert Ames, had just recently deposited $75,000 with the bank. According to the Grange Advance newspaper in Red Wing, three men went inside and told the cashier to open the safe, which he refused to do, so they killed him.

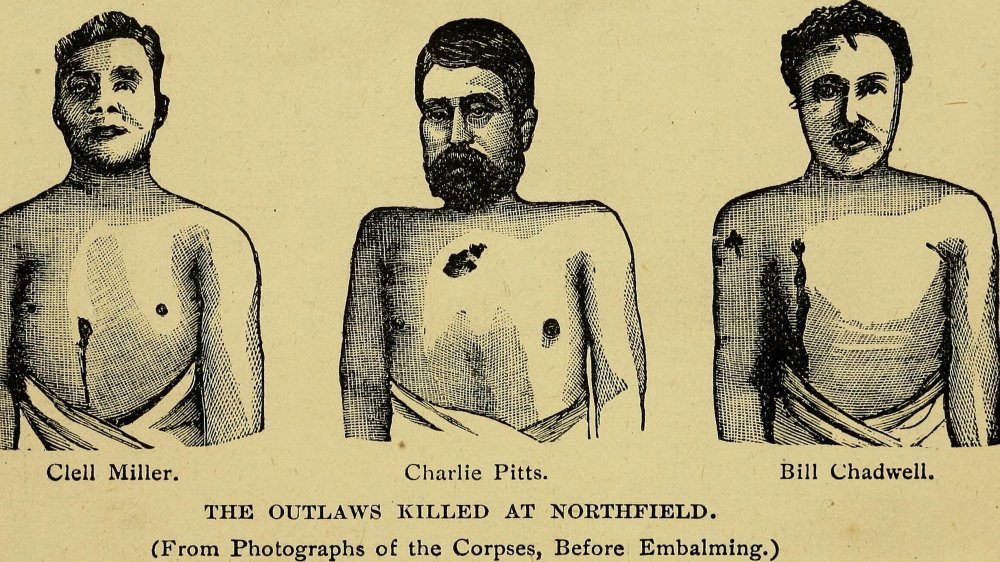

The others remained outside as a lookout, but word quickly got out of the hold-up. Angry townsfolk took up arms and approached the robbers in the street. In the ensuing gunfight, two members of the gang, Charley Pitts and Bill Chadwell, were killed (although some sources say the other bandit was Clell Miller). The others fled sans any money, but with a few gunshot wounds. The Younger brothers were captured two weeks later near Madelia, Minnesota and were later sentenced to life in prison.

The failed robbery was a lesson to Frank and Jesse, who decided to remain in Tennessee under assumed names to avoid capture. After two years of living peaceably, however, Jesse decided to resume his life of crime.

A new crime spree and Jesse James' supposed death

By the summer of 1879, Frank James had decided to leave his lawless life behind. For Jesse James, however, going straight was not so easy. Riding back to Missouri, he began looking around for a new set of gang members. HistoryNet reports one of them was Ed Miller, Clell Miller's brother. Ed decided to introduce Jesse to the Ford family outside of Richmond. Jesse felt at ease with the Fords, especially Bob and Charlie, who were fellow guerrillas from the Civil War days. The new gang committed at least one robbery, in 1879. According to the Leavenworth (Kansas) Weekly Times, the boys raided an "express train on the Chicago & Alton Road" in October.

Soon, however, Jesse was shocked to learn that America was under the impression he had been killed by one George Shepherd. An incensed Jesse wrote a letter to the Clipper-Herald in Hannibal, from "Brownwood, the Hardest Town in Texas." The letter read, in part, "Your reporter and George Shepherd have the most brilliant imaginations in America ... I read your reporter's yarn, and myself and wife laughed heartily over it." The outlaw even teased that he was now living in Brownwood under an assumed name. "Tell your reporter to 'set 'em up' to the boys around and send the bill to me," he wrote. He even enclosed a photograph of himself for all to see, although the paper didn't publish it.

Jesse James' sense of humor versus his nasty temper

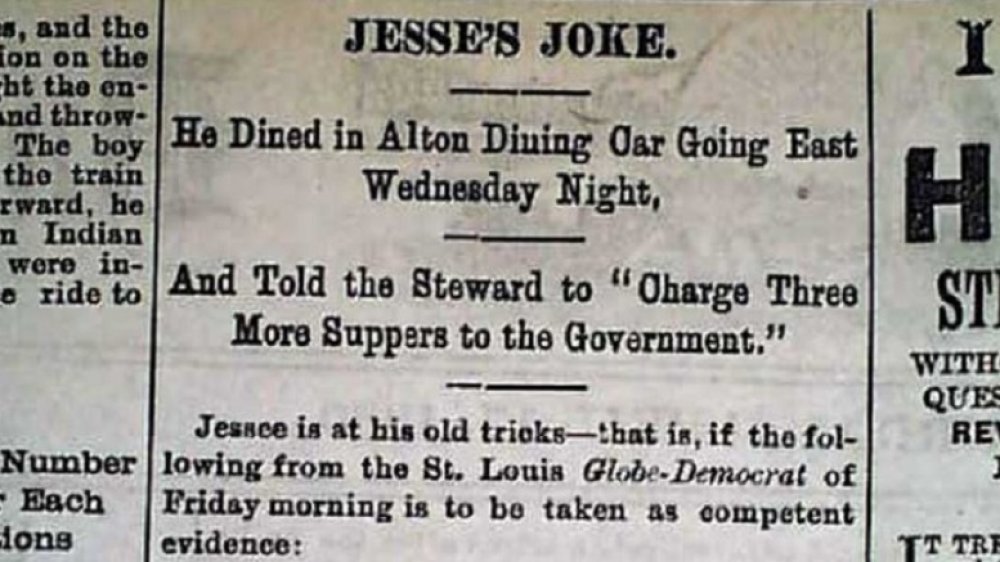

James remained in good humor, perhaps even faking his own death on occasion to get the best of his adversaries. In 1880, the Russellville Democrat published a rather humorous article stating that James and two gang members even boarded a train in Kansas City long enough to chat amicably with others and eat a meal. As the train neared Odessa the men took their leave, with James calling out cheerfully, "Charge three more suppers to the government!"

HistoryNet says James also remained appreciative of Ed Miller for introducing him to the Fords — at least until the summer of 1880, when Miller announced he wanted to leave the gang. James immediately suspected Miller of betraying him and shot him to death. James next appeared at the Ford house with Miller's horse, which he left there with the explanation that ol' Ed was on the mend in Hot Springs, Arkansas from some ailment.

A member of the Ford family, Jim Cummins, grew suspicious. After looking for Ed Miller for awhile, Cummins visited James in Nashville during the winter of 1880-81. As with Miller, James became suspicious of Cummins when he asked too many questions. Cummins took off in night, fearful that he too might become one of James' victims.

A book about Jesse James and a deal

As Jesse went after those who seemed to betray him, a whole new set of troubles appeared on his horizon. In 1880, Joseph A. Dacus published "a carefully prepared" book titled Life and Adventures of Frank and Jesse James. Gleaned from years of interviews with Jesse's family and friends, Dacus sought to tell the truth about the outlaw brothers. The book sold like hotcakes — 21,000 copies in four months (knowing a good thing when he saw it, Dacus's second book, The Illustrated Lives and Adventures of Frank and Jesse James, would come out in 1882).

The book might have spurred both Jesse and Frank to resume their lives of crime with a vengeance. There were more robberies, more killings. But when Jesse again took up his hunt for Jim Cummins and roughed up a 15-year-old member of the Ford family, the Fords had enough, according to HistoryNet. In the fall of 1881, a meeting was arranged between Bob Ford and Governor Thomas Crittenden, during which Ford agreed to capture Jesse James. Ford would later claim he had agreed to get Jesse "dead or alive."

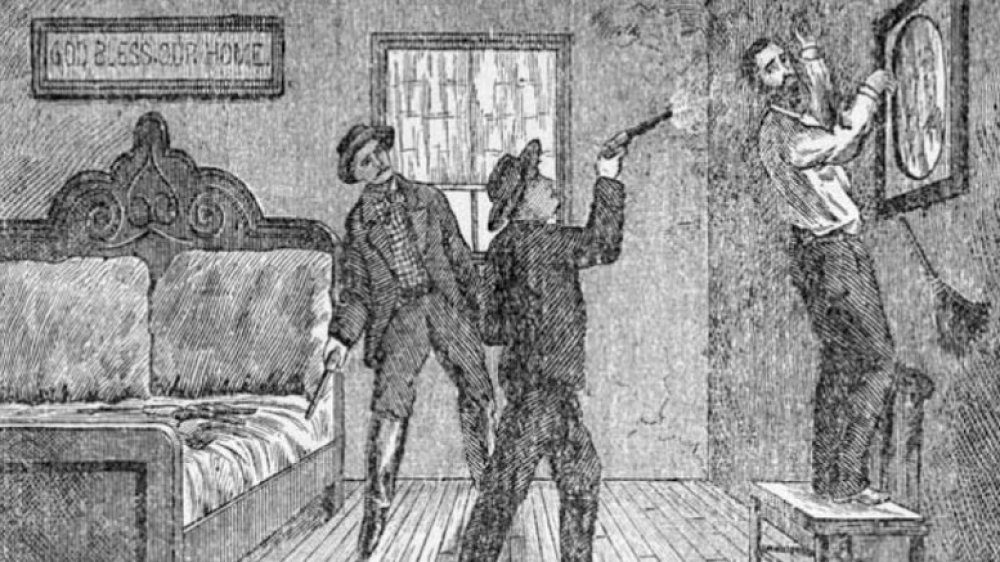

The death of Jesse James

In early March of 1882, Jesse and the Fords began planning several bank robberies in Kansas. Charlie and Bob had moved into the James home, where they awaited their chance to take the outlaw. On the morning of April 3, Zee was in the kitchen as the men chatted in another room. Jesse had taken off his pistol belt, "for fear somebody will see them if I walk in the yard." Next, he hopped on a chair to dust some pictures on the wall. Behind him, Bob and Charlie quietly drew their guns. Jesse heard a noise behind him and was turning to look around when Bob shot him in the back of the head.

Zee rushed into the room to see her husband lying on his back as the Fords ran towards the back fence outside. "Robert, you have done this; come back!" she shouted. "I swear to God I did not," replied Bob as the brothers re-entered the house. Jesse was not quite gone, trying to say something to Zee as she cradled his head and attempted to wipe off the fast-flowing blood, but unable to get out any haunting last words. Within seconds he was dead. Charlie then explained that a "pistol had accidentally gone off." In a 2006 issue of Wild West magazine (via HistoryNet) Ted Yeatman, long considered the foremost authority on Jesse, wrote that the grieving Zee replied, "Yes, I guess it went off on purpose."

Jesse James' legacy and the end of Bob Ford

Jesse James was buried at the family farm as America revered his death. His widow Zee was forced to sell everything, including the family dog, to stay afloat. Several historians, including David Hamilton Murdoch, author of The American West: The Invention of a Myth, discovered that in the coming years Zee, her landlord Henrietta Saltzman, James' mother and even his brother Frank kept the James home as a tourist attraction and charged admission.

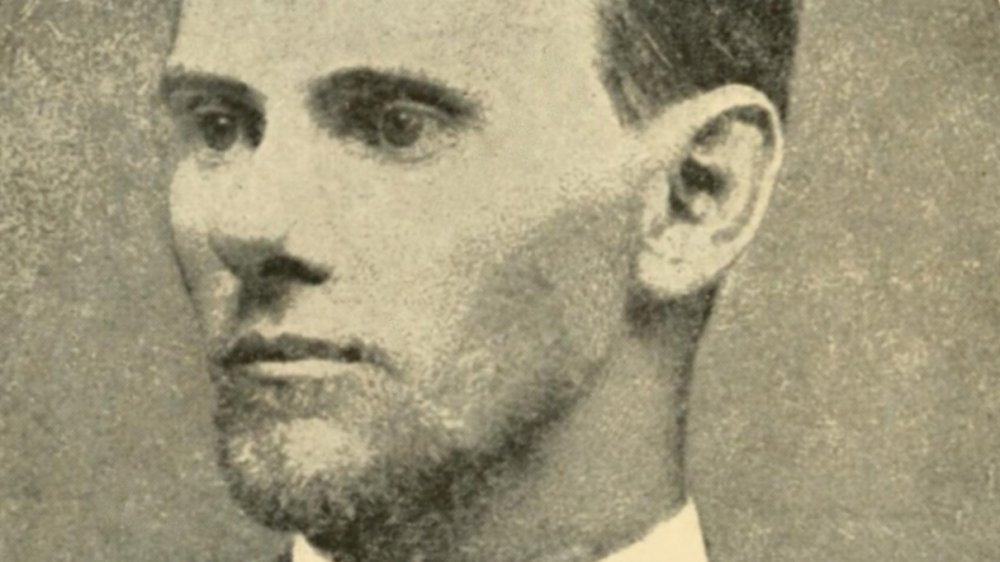

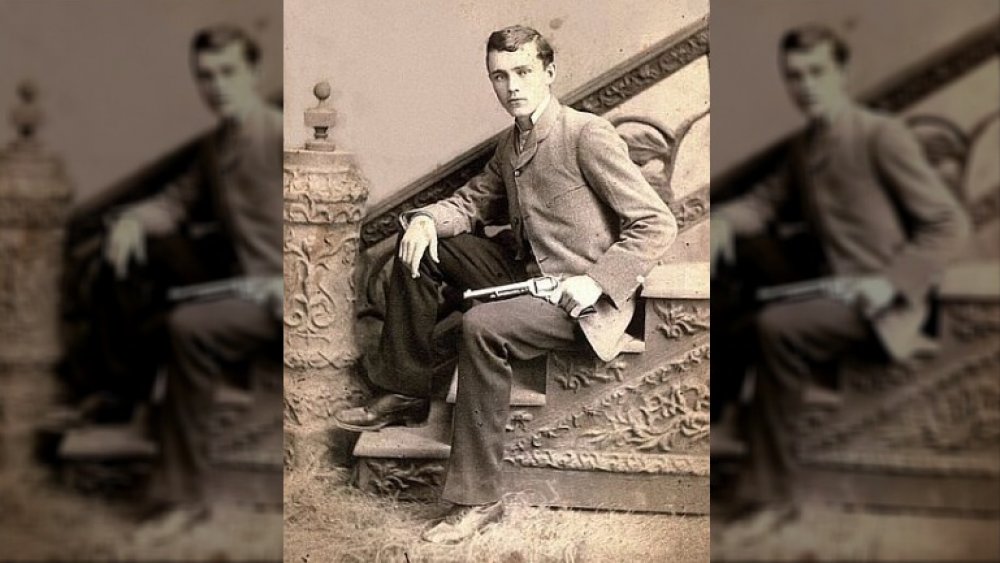

Because he killed Jesse James rather than apprehending him as agreed, Bob Ford (pictured) was denied any reward money and even arrested for murder. He was later pardoned and began roaming the country telling (and selling) his story, although his actions caused many to believe he was a common coward for shooting James from behind. By 1889 Ford was in Colorado, dealing cards in (Old) Colorado City and opening a bar in Creede in 1891. He often traveled between the two places. Notably, he was turned away from the city limits of Cripple Creek by the sheriff himself in 1891. In 1892, a rumor circulated that he had been killed. But Ford remained very much alive — until 1894, when one of his enemies, "Red" Kelley, waltzed into Ford's Creede saloon. Kelley called out, "Hello, Bob!" before firing a double-barreled, sawed off shotgun a mere five feet from Ford's throat.

Today, the story of Jesse James remains as one of the best-known, and most debated, tales of the West.