10 Bizarre Artifacts Discovered At Pompeii

One day in A.D. 79, Mount Vesuvius, a volcano that still looms over the city of Naples, roared into life. The erupting volcano blanketed the nearby city of Pompeii and some smaller adjacent towns with ash, pumice, and hot gas, killing many inhabitants and sealing them, their homes, and their possessions away for centuries under several meters of debris.

While the site had been rediscovered earlier, excavations of the lost cities did not begin in earnest until the mid-1800s, a development that marked the start of modern archaeology. Excavations have continued ever since, with some interruptions (for example, World War II). The city has provided archaeologists and history buffs an unparalleled glimpse of how Romans actually lived, with the speed of the destruction and subsequent years of protection from interference preserving a snapshot of a day in a Roman city that, despite its horrifying end, began like any other.

While some mysteries about Pompeii remain (and are likely to endure indefinitely), the site, filled with everyday Roman goods and human remains, has answered countless questions about Roman life. Among the artifacts discovered at Pompeii are some fairly bizarre finds: some underscoring the humanity these Romans shared with modern people, and others emphasizing the ways the antique world differed from today.

Bread

They're probably a bit stale, but to be fair, they're nearly 2000 years old: loaves of charred bread are among the fascinatingly everyday objects unearthed at Pompeii. Organic relics like food are relatively rare finds in archaeological sites, as decay or scavengers usually consume them. At Pompeii, the heat of the gases that flooded the doomed city quickly carbonized the bread, rendering it safe from decomposition and unappetizing to any enterprising vermin digging through the rubble. Today, we have a humanizing glimpse at the literal daily bread of the everyday Roman.

The bread found at Pompeii appears to be a type called panis quadratus, a type of segmented sourdough common in that region of the Roman world at that time. A typical loaf would weigh in at a little under 3 pounds and was probably mostly made of simple wheat flour, though extras like honey, seeds, and herbs may have been included. The central hole appears to have had a string passed through it, which bakers and archaeologists (and a few lucky people who are both!) think either helped consumers carry the bread or cut it into segments for sharing. Enterprising food historians have replicated the recipe and describe it as a chewy whole-wheat loaf, one that might go well with a rich autumn soup.

Glass

Romans were expert producers and enthusiastic consumers of glass products, and a number of such relics have been unearthed at Pompeii. Glass had been made and worked in the ancient Mediterranean for centuries, but the Roman industry appears to have arisen and developed in a fairly short time in the early first century. After this industry bloomed, glass was sent all over the empire and to trade partners. Glass's discovery in archaeological sites is not rare, but the intact artifacts at Pompeii are.

One particularly lovely but sadly ironic example of Roman glass unearthed at Pompeii is a blue urn containing human ashes, buried along with coins to pay the deceased's fare to the afterlife some time before the fire. Glass seems to have been omnipresent for the living as well, providing various household vessels and containers as well as windowpanes, which had recently been invented. Pompeii was a center of the perfume-making industry of the Campanian region, and so its artisans needed glass containers to store and ship their products. Chemical studies of glass found at Pompeii indicate that, even though fresh glass was available, a productive glass recycling system existed, and that at least one workshop existed that made blown glass, a Levantine innovation that was relatively new at the time of Pompeii's burial.

Erotic art

One charming but occasionally startling fact about the ancient Romans is that they both loved and were amused by sex. Many of the walls in Pompeii are decorated with frescoes that have been preserved, and many of these frescoes depict various sexual acts, with varying degrees of technical skill and explicitness. The acts depicted range from the relatively staid (heterosexuality in a conventional position) to the more outré: orgies, mythical figures copulating with animals, homosexuality, and orgies are all represented among the erotic works, along with a number of disembodied phalluses.

These works adorned both private homes and public buildings, including public baths and what researchers believe to have been brothels. In the brothels, the works had an obvious potential role as inspiration, perhaps even serving as advertisements. In baths, they may simply have been for decoration and pleasure, as well as perhaps providing a visual reference point for where an individual bather may have left his clothes. The presence of erotic scenes in private homes is especially interesting for modern viewers. Comparable decor would be rare today, but the Roman zest for sexy scenes helps us see them as entire, well-rounded human beings.

Some of the bonanza of erotic depictions unearthed at Pompeii was housed in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples and intermittently concealed from public view from about 1849 to 2000, when the "Secret Cabinet" was fully opened to the admiration (and occasional giggles) of the general public.

Garum containers

At the other end of the olfactory spectrum from its perfumeries, Pompeii also produced garum, a stinky but beloved sauce made of fermented fish that the Romans ate and exported extensively. (It's a cousin of Asian fish sauce, and a fermented anchovy sauce called colatura de alici is still made in Italy for the curious.) The umami-rrific result of sun, salt, and time on a wooden barrel full of little fish was popular on Roman tables, but its production was banned in some areas (because of the odor), so Pompeii's role as a significant garum producer brought it both commerce and a degree of gourmet cred. Garum was one of a handful of similar sauces made from different parts of different fish; wine, vinegar, and/or honey could also be added to vary the flavors present.

One of the wealthy Pompeii residents whose home was excavated was a freedman named Aulus Umbricius Scaurus, whose wealth came from his business selling garum and similar fish sauces. The unearthed floor of his house's atrium bears tile mosaics portraying jars of this salty brown moneymaker — jars similar to the terracotta amphorae found throughout Pompeii, some of which would have contained garum at some point in their liquid-holding careers. Sadly for the curious gourmand hoping for a whiff of this distinctively Roman condiment, the smell has faded over time.

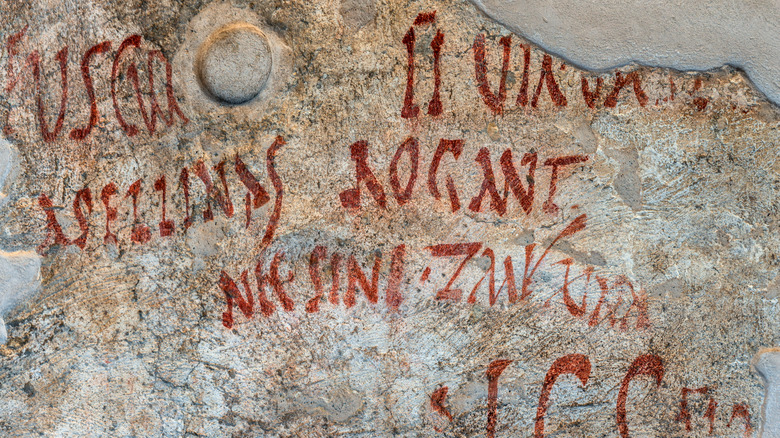

Graffiti

Most people imagine the Roman world as a lot of clean white marble: austere, pristine, and suspiciously clean. But as Pompeii's artifacts constantly remind us, the Romans were as human as we are, and one of the things Romans most enjoyed was writing or scratching graffiti on walls. Like modern people, Romans who added graffiti to walls tended to write about what they happened to be thinking about; like modern people, these topics were very often poop and sex, although these are rounded out with political comments and declarations of love, filling out our understanding of the common Roman's psyche.

Walls warned passersby not to defecate or fornicate nearby (a reasonable request, in most instances). Disappointed diners trashed restaurants and pointed fellow travelers to bars in other cities. People, generally men, bragged about their sexual exploits with members of both sexes, with one man even taking his farewell of women's company for good, as he'd realized he now preferred men. (His exact words are less delicate.) There are wanted posters, insults, and even the timeless classic "so-and-so was here." These graffiti have proven to be valuable as an academic resource and so popular among the public that interactive maps of Herculaneum and Pompeii have been generated.

Surgical tools

Surgical instruments found at Pompeii offer a valuable, if often squirm-inducing, look at how medicine was practiced in the ancient Mediterranean. While most of the tools were found at a structure called the House of the Surgeon, medical tools have also been found in various parts of the excavated city. Many of these tools were made of copper alloys, and while Romans did not yet have germ theory, they used copper in some medicines, and the copper in these tools may have prevented infection thanks to copper's antimicrobial properties.

And Roman patients would have needed the help. Among the tools unearthed were a variety of vaginal speculums, depressingly similar to those in modern gynecologists' offices. Scalpels are of course present, as are specialized tools called osteotomes to cut bones. Cups to capture blood during the long-lasting practice of bloodletting have been found, along with cautery kits used to apply heat and stop bleeding when necessary. Probes and catheters are recognizable, as are a wide variety of tongs, forceps, and other generalized poking and prodding instruments. Clysters — reusable enema administrators — add an unnerving example of thrift, and surgical scissors may have been used to cut hair, which is described by some classical authors as a medical procedure; a glimpse at the comparatively crude shears will certainly make you hope so.

Fall clothes and foods

Some 20 years after the eruption at Pompeii, the historian Tacitus wrote to a prominent Roman, Pliny the Younger, to ask about the event and, more specifically, the death of Pliny's uncle Pliny the Elder. The surviving Pliny obliged, and the resulting letter is the only firsthand description of the catastrophe of Pompeii. He describes his uncle's efforts to save friends stranded near the danger, comments on a nap his uncle took and the resulting snoring, and transmits reports he'd received of Pliny the Elder's ultimate death from suffocation by gases emitted by the explosion. Pliny closes by emphasizing that everything he writes, he either saw or learned shortly after the explosion: it's all true, and Pliny gives the date of the disaster as August 24.

Why, then, were some of the dead found in heavier clothes than August in the Mezzogiorgno would require? How were chestnuts and other fall crops among the preserved foods identified, and why did people have heating braziers out? In 2018, a charcoal graffito was found that gives the date as mid-October, meaning that the blast happened after that date, with scholars now suggesting October 24, not August, as the fatal date.

This can be squared with Pliny's account when we take into account that we don't have his original letter, but instead only copies and transcriptions that don't all completely agree. Add to this the fact that the "octo" in "October" refers to its former position as the eighth month, and the mistake is suddenly understandable. It was a crisp fall day, not a summer scorcher, in which the volcano was immortalized.

Water infrastructure

Pompeii had a sophisticated water management system for the time. Initially, people in the area had built cisterns to catch and store rainwater, which remained a source of water for household use. But by the time of Pompeii's destruction, the city was connected to an aqueduct that provided settlements in the Bay of Naples with water from a spring 94 kilometers away. This made it possible for Pompeii's residents to enjoy running water in both homes and public spaces.

Water went to public fountains and baths for general use, but some homes were apparently also hooked up to the system, which was kept pressurized by elevated water towers. Fixtures have been found that clearly resemble modern faucets, and the fountains in upper-class homes were fed with water for household use. Pompeiians even enjoyed an early style of flush toilet, though the "flush" was manually provided by throwing in a bucket of water. Finally, a system of drains carried the city's runoff toward the sea.

Nothing is perfect, of course. Many of the pipes revealed in Pompeii were, like pipes elsewhere in the empire, made of lead. Ancient plumbers chose lead for such projects because it is easy to work and does not rust; it's also extraordinarily toxic, with no safe level of exposure.

Snack bars

Pompeiians in a hurry could grab a quick bite at antiquity's equivalent of a snack bar or fast food joint. Excavations in Pompeii have revealed a number of businesses that seem to have specialized in quick, easy meals. These would have been enjoyed by lower classes, in all likelihood: the rich had their own kitchens with slaves or servants to work in them, so had little need for convenience food. The less affluent may not even have had their own kitchens, and so they would have formed these restaurants' clientele.

Decorated with frescoes, these snack bars feature a number of built-in spots for pots or dishes. Archaeologists have found traces of the grains, cheese, and olives one might expect from southern Italy, along with proteins like fish, duck, chicken, goat, and snails, among others. Wine was probably a popular drink, as it was in much of the empire, although likely diluted with water to allow diners to function for the rest of the day.

A quick terminological note: the word "thermopolium" has caught on to describe one of these eateries (plural "thermopolia"), but this seems to be a joke word invented and used by the writer Plautus. Eminent classicist Mary Beard, among others, doesn't care for this usage; Beard noted on X, formerly known as Twitter, that the contemporary term would have been "taberna" (compare "tavern") or "popina."

Human remains

The most arresting artifacts at Pompeii are the human figures. These familiar shapes show the inhabitants of the doomed city as they were in their last moments: in kitchens and gardens, fleeing or hiding, in groups or alone. The recognizable postures and attitudes underscore the humanity of the dead, reminding viewers that lives like ours were lost in the calamity.

Strictly speaking, the familiar human shapes from Pompeii are not remains: they're casts. During excavations in the 1860s, archaeologists discovered voids in the debris layer, eventually realizing that these were shaped like human bodies. Some of the dead of Pompeii had been sealed under a layer of ash and pumice cool enough to preserve their forms. This then hardened, and when the bodies decayed over time, they left behind these haunting chambers. The archaeologists realized they could pour plaster into these chambers and create casts replicating the shapes of the bodies, and it is these casts that have become famous as images of the victims of Pompeii.

New casts are still being made today, using a similar process; today's researchers are also able to find DNA traces in the chambers or on casts to investigate the genetics of the victims. Some are even do-overs: Pompeii suffered bombing during World War II, and some of the original casts were lost. Of the 1000 sets of remains that have been found, a little over 100 have had casts taken of them. These ultra-vivid reminders of the people who lived and died in Pompeii are one of the most arresting achievements of Pompeii's generations of excavators.