12 Historical Artifacts That Are Said To Be Cursed

People might say they're scared of cursed objects (along with cursed songs and curses said to haunt families), but many love hearing about it all anyway. Plenty others are also skeptical of the whole idea — really, a haunted chair? A cursed painting? Malevolent statues? But we also all enjoy a good story. A proper legend can transform an ordinary old chair or discarded toy into something full of malevolent power. It can also present a good inroad to learn more about the deep history of an object or place.

Take the Hope Diamond. Its story is rooted in the gemstone-related history of India, where it likely originated from the Kollur mine. But also has its tendrils in many other world events, from the glittering court of French king Louis XIV to its present-day home in Washington, D.C.'s Smithsonian. If your tastes run less to the glitz and glam of potentially cursed gemstones, there are also many seemingly everyday objects haunted by tales of tragedy. Or, as some legends go, tales of annoyance and misfortune tinged by history.

Busby's stoop chair

Busby's stoop chair is hardly attention-grabbing, but its story is. The precise origins aren't easy to tease out, but legend says that Thomas Busby murdered his father-in-law, Daniel Auty, near the town of Thirsk in North Yorkshire. Condemned to hang, Busby requested that he make one stop before the gallows: the Busby Stoop pub. Having downed his last beer, he proclaimed that anyone who sat in his chair would die. That's all unverified, though contemporary historian Ralph Thoresby did record passing by Busby's displayed remains in 1703.

Real or not, the story of the curse naturally led to many an ale-fueled dare in which people placed their seat upon the chair. Legend goes that many who did fell from roofs, died in car crashes, or otherwise mysteriously fell dead. During WWII, a group of Canadian airmen visited the pub and, as it's retold but not necessarily confirmed, those who sat in the chair never returned from their missions.

Eventually, the pub owner donated it to the local Thirsk Museum, where it was displayed hanging from the ceiling. However, as The Northern Echo reported, this move also allowed historians and furniture experts to take a closer look at the chair. They found that it appeared to have been machine-made sometime in the mid-19th century, well after Busby's execution.

Forres witches stone

Starting in the 1590s and continuing into the 1660s, Scotland was gripped by a series of witch panics, perhaps made all the more dire by the growing rift between Protestantism and Catholicism and the dramatic rise of the Protestant Scottish Reformation in the 1560s. No wonder some people thought that witches and demons were out to get, well, everyone. In 1563, the country even introduced the Scottish Witchcraft Act, which made witchcraft an execution-worthy offense.

Accused witches were therefore rounded up and subjected to brutal punishment (some sources suggest about 4,000 people died as a result of the panics). In Forres, Scotland, this is allegedly represented by a large, broken boulder at the base of a hill. A sign proclaims that condemned witches were taken to the top of the hill, each placed in a barrel full of spikes, then rolled down. At the bottom, the barrel and its occupant were burned, with the stone said to mark the site of one such immolation.

To many, this means the stone is bad news. Legend maintains that the boulder was broken up to be used in local home construction. and it does appear to be cracked and reassembled with metal reinforcements. It's said that the stone fragments made occupants grow mysteriously ill, forcing locals to remove the offending building material and return it to the original resting spot.

The crying boy paintings

Cheerfully displaying a mass-produced picture of a child in distress probably sounds odd, but things were just different in the '80s. During that era in England, just such a painting hung on the walls of homes across the nation (most were actually sold from the 1950s to 1970s). But then they started to gain a darker reputation. By the middle of the decade, some noted these paintings had an odd habit of surviving destructive house fires. As the 21st century dawned, the legend was often embellished with the detail that its subject was crying because he had orphaned himself by starting a house fire (or who was the source of mysterious fires, or who died in a sudden explosion, as more colorful versions have it).

However, these allegedly cursed paintings actually depict different boys, and there's no confirmation that any were arsonists. When comedian Steven Punt found a painting and set it on fire for the BBC, he and researcher Martin Shipp found it really was hard to set ablaze. Their conclusion? The varnish layered on top appeared to be fire resistant, as did the board it was painted on. Moreover, the string used to hang it readily burned away, which meant that paintings could have quickly fallen to the floor and escaped the worst of the flames.

Robert the Doll

With some very respectful apologies to one particular toy who might just be reading, we have to admit that the story of Robert the Doll is especially creepy. Robert — who may have inspired horror icon Chucky the doll — was the toy of Robert Eugene Otto, who grew up in Key West, Florida and became an artist (and who went by Gene, perhaps to avoid confusion). Robert the Doll was so beloved by Eugene that people around him began to think the attachment was getting weird.

Weirder still are accounts that claim Robert began to do things on his own. Young Gene would allegedly blame incidents on Robert and, as he grew older, others claimed to see or hear evidence of Robert moving on his own. Gene died in 1974 and his home, naturally known as the Artist House, was rented out. Robert came with the place and was said to have terrorized tenants, repairpeople, and others by giggling, moving, and even changing expressions.

In 1994, Robert was donated to the Fort East Martello Museum. By then, he had grown notorious and began to receive quite a few visitors ... not all of whom behaved. But Robert appears to get his revenge on rude guests, at least going by the numerous letters sent to Robert apologizing (mostly for taking pictures or entering the space without first asking permission) and asking for his curse to be lifted.

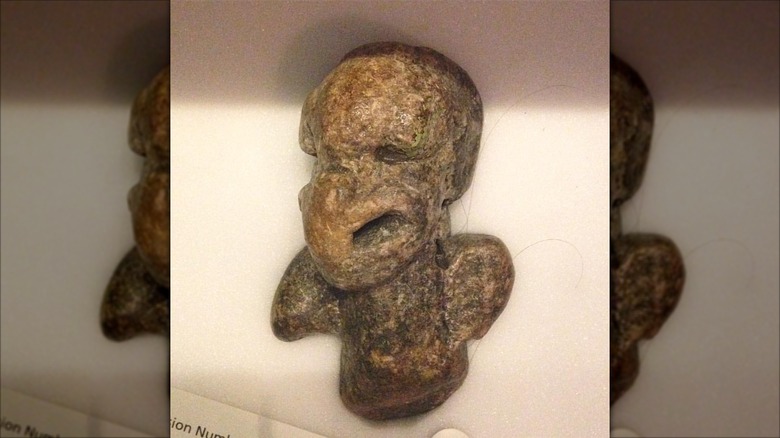

The Little Mannie

Looking at the sculpture now popularly known as Little Mannie, it can be hard to understand what you're viewing. The very worn, three-inch stone carving was found by a cleaning lady in 1960s England who was scrubbing a packed dirt floor in a 17th-century building. Further investigation found a buried circle of candles, animal bones, and other carvings perhaps meant to bless the structure. By the 1970s, some guessed the Little Mannie — short for "Little Mannie with his daddy's horns" — was left behind by Celtic people. The notion was supported by evidence that Little Mannie had once been painted green, maybe in reference to magical activity. He also has strands of hair wrapped about him, either also part of a ritual or merely a stray tangle.

When Little Mannie was taken in by the Manchester Museum, archaeologist and curator A.J.N.W. Prag wrote that he and other museum workers began to experience odd misfortunes, though it was largely on the level of scraped car doors, bonked heads, and a failed pants fly (via "The Materiality of Magic"). Eventually, an African art expert said that the figure wasn't Celtic at all. Instead, it's almost certainly a West African nomoli figure. How it got from there to England remains a mystery — Prag suggests a French priest might have brought it there for help from a fellow priest. But perhaps Little Mannie is none too happy about being taken from his original home.

The Hope diamond

How can a rock become one of the most famous curses of all time? In the case of the Hope diamond, it's either because of very real misfortunes or really excellent marketing. It first popped up in the possession of merchant Jean Baptiste Tavernier, who purchased a massive 112 3/16-carat blue-violet stone, likely from India. He sold it to Louis XIV of France in 1668. Five years later, it was cut down into a smaller but still considerable 67 1/8 carats. Ultimately, it ended up in the French Royal Treasury, where it was stolen during the French Revolution.

It popped up in London before traveling through a variety of owners, including Henry Philip Hope (who lent his name to the gem) and American socialite Evalyn Walsh McLean. In the 1940s, Harry Winston Inc. purchased it, then it donated the gem to the Smithsonian in 1958. Today, visitors to the National Museum of Natural History can view the stone in its diamond-encrusted necklace setting.

Rumors of a curse didn't pop up until shortly before McLean's 1911 purchase. They appear to have been partially invented by newspaper writers who couldn't resist a good story (but could resist fact-checking) and sellers like Pierre Cartier, who sold McLean both a diamond and legend. While some deaths, divorces, and financial woes were reportedly tied to the stone, it's worth noting that McLean held onto the Hope diamond for decades before her own peaceful death in 1947.

Ring of Senicianus

Made somewhere between 350 to 450 A.D., the gold Ring of Senicianus was lost near the Roman settlement of Silchester in what's now England. Centuries later, just north of Basingstoke, Hampshire in 1785, a farmer rediscovered the ring. The inscription references both the Roman goddess of love, Venus, and the Christian God (the juxtaposition of Christianity and pagan belief wasn't quite so strange in Roman times).

Around the same time, someone uncovered an inscribed bit of lead likely from a nearby Roman temple. Now called the Lydney tablet, it says a man named Silvianus lost a ring. "Among those who are called Senicianus do not allow health until he brings it back," it reads, implying that Senicianus was a cursed thief (via National Trust Collections). People then connected the angry text with the Ring of Senicianus, though there's no clear proof of the link.

We can't really ask an ancient Romano-Briton man named Senicianus if he was cursed, but at least there are no known reports of the ring bothering any modern folks. Legend has it that it was among real-world objects that inspired J.R.R. Tolkien's Lord of the Rings, who visited archaeological sites in the area. Not long after his visit to the ancient temple, he started work on "The Hobbit," which includes a now very-famous, very-cursed fictional ring.

The Conjured Chest

A cursed chest of drawers sounds like the plot of a mid-career slump Stephen King novel ... until you learn that it's a very real object in the possession of the Kentucky Historical Society. To be fair, the society cautions that it's just a legend with some verified details and many more that remain murky. It all started, it is said, with a new baby. Around 1830, a man named Jeremiah Graham had a chest of drawers made in anticipation of his first child's arrival. An enslaved man, Remus, crafted the piece of furniture, but Jeremiah, somehow displeased with the result, beat Remus so badly that he died. In revenge, other enslaved people cursed the chest. Anyone who put their clothes inside was said to die, leading to 16 deaths (17 including the killing of Remus). Finally, a maid named Sallie broke the curse with conjure work of her own, though it took her life, too. Today, owl feathers in the top drawer are purportedly remnants of Sallie's curse-breaking efforts.

There are some tricky aspects to this story. It was first written down by family member Virginia Cary Hudson Cleveland, born many years after the cursed chest was made. She said that the legend was passed down orally within the family. But legends can take on new shape over the generations, though you may still wish to avoid putting your clothes inside.

The Cursed Amethyst

Though it's now in the United Kingdom's Natural History Museum, the Cursed Amethyst's mysterious history began in India. Previous owner Edward Heron-Allen claimed in a 1904 letter that it was stolen from a temple by Colonel W. Ferris amidst colonial unrest. Though he made it back to England, Ferris, his family members, and their friends reportedly experienced a bevy of misfortune including poor health, sudden death, and financial woes.

Heron-Allen claimed that upon receiving the amethyst in 1890, he was also affected by the curse. Despite his best efforts — which included setting it alongside other ancient and mystical items and tossing it into a canal — the gem kept returning and bringing bad luck with it. One singer friend allegedly lost her voice after taking possession of the stone, and after the canal incident, it was dredged up and restored to him in short order.

Finally, Heron-Allen admitted quasi-defeat, locking it away in seven nested boxes within a bank vault. After his death, his daughter donated the Cursed Amethyst to the Natural History Museum, though her father had hoped otherwise. "Whoever shall then open it, shall first read out this warning, and then do as he pleases with the jewel," he wrote. "My advice to him or her is to cast it into the sea." Curators have since noted odd occurrences possibly linked to the gem, like mild illnesses or intense storms during transport, but that's far tamer than sudden death.

The Bronze Lady of Sleepy Hollow

Sleepy Hollow, New York has something of a spooky reputation. It was once a truly sleepy little village about 25 miles north of New York City, but it got spooky with the 1819-1820 publication of "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" by Washington Irving, which related the in-story legend of a headless horseman. But the real-life Sleepy Hollow Cemetery might just contain a true cursed object.

Known as the Bronze Lady, this statue depicts a larger-than-life woman mournfully staring at the tomb of General Samuel M. Thomas, a Civil War veteran. Thomas' widow commissioned artist Andrew O'Connor Jr. to make it in 1903 after allegedly complaining that the statue wasn't cheerful enough. O'Connor agreed to make a replacement head, and he reportedly did so — only to smash it to pieces in front of her, making the point that a smiling graveyard statue wasn't quite his style.

Local legend has it that anyone who mistreats the statue or climbs into her oversized lap would be haunted by the vengeful lady (in some retellings, being nice gains you protection courtesy of the Bronze Lady). Others claim to have found real tears on her face. Some allege that if you get into the statue's lap and then climb down and look through the keyhole of the Thomas tomb, you'll see a ghost, be plagued by bad dreams, or once again bring down a curse upon yourself.

Man Proposes, God Disposes

Just by looking at "Man Proposes, God Disposes," you will likely get a pretty eerie feeling. The 1864 oil painting by Edwin Landseer shows two polar bears tearing at the remnants of a wooden ship and its long-gone occupants. It references the lost Franklin Expedition, which set off in 1845 to find a sea route through northern Canada known as the Northwest Passage. The two ships and 129 men commanded by Sir John Franklin were never heard from again, apart from an 1848 letter left behind by straggling survivors noting his death and the abandonment of both ships.

The painting generated much interest and controversy, and in 1881, it was purchased for Royal Holloway College, University of London. It remains there today, but students aren't especially fond of it. Popular rumor alleges that not only is the painting difficult to look at, but it may be cursed.

Legend has it that students who are seated near the painting during exams are doomed to fail, though their stumble probably wouldn't be as dire as that of the Franklin Expedition. By the 1970s, students refused to be seated near it. One exasperated administrator found a large covering — a nearby Union Jack flag — and flung it over the oversized painting. Since then, the flag has been draped over the painting during every test in its room.

The Terracotta Army

In 1974, farmers digging a well in China's Shaanxi province uncovered fragments of a life-sized clay figure. Eventually, archaeologists uncovered thousands of terracotta soldiers, animals, and courtiers. About 8,000 of these were interred as part of the sprawling funerary complex of China's self-proclaimed first emperor, Qin Shi Huang, who died around 210 B.C.

One of the original excavating farmers, Yang Quanyi, told the South China Morning Post, some locals worried that the unearthed terracotta was part of a religious statue that might bring a curse. Then, the Chinese government seized much of their farmland and didn't provide much to make up for the lost income. As Yang Quanyi noted, the discovery happened "[in] the days of collective farms and we were given 10 credit points by our brigade leader for finding the warriors. That was the equivalent of about one yuan in our pay packet at the end of the month."

The farmers effectively got nothing more than a pitiful bonus and swarms of archaeologists, government officials, and tourists for their trouble. Some of the original group, now unable to afford medical care, succumbed to treatable illnesses. At least two associated people reportedly died by suicide. As Yang Quanyi's wife Liu Xiqin told the South China Morning Post, "He's afraid they might have brought misfortune in some way — and does still wonder if maybe the soldiers should have been left beneath the ground."