The 10 Most Bizarre Coincidences Of World War II

Perhaps it isn't quite so surprising to learn that World War II has some odd coincidences. After all, it was a massive, deadly, globe-spanning war that involved some 100 million fighters (not counting civilians who supported war efforts or were caught up in the conflict) and over 50 different nations. On the one side were the Allied powers, led by the "Big Three" of the Soviet Union, Great Britain, and the United States, the last of which entered the war shortly after the December 1941 Japanese attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. On the other side, the Axis powers were headed by Germany, Japan, and Italy. With those sorts of numbers and players involved, weird accidents, instances of providence, and unexpected crossovers are bound to happen.

And yet, it's hard to ignore some of the more bizarre coincidences and eyebrow-raising connections that happened during and around the course of World War II, which officially kicked off in 1939 and finally ended in 1945. From a medieval warlord who may or may not have had a role in the Soviet Union's entry into the war, to the strange reoccurrence of flunked-out chicken farmers in Europe, this conflict contains quite a few bizarre examples of happenstance.

A series of coincidences linked a long-dead warlord with the outbreak of war

What does a 14th-century Central Asian warlord have to do with World War II? If you ask some people, everything. It all begins with Timur, a conqueror whose bloody campaigns, canny military strategy, and artistic and architectural legacy were so profound that he became a cultural figure in far-flung parts of the world and a highly regarded military commander. (Sixteenth-century English writer Christopher Marlowe's first play, "Tamburlaine the Great," cemented him in literature syllabi for generations to come.)

Centuries later came Mikhail Gerasimov, a Soviet archaeologist who specialized in reconstructing the faces of historic figures — Timur included. In 1941, Soviet premier Joseph Stalin essentially told Gerasimov to hustle off to Uzbekistan and open Timur's architecturally stunning tomb, Gūr-i Amīr. Locals were none too happy about the plan, but Gerasimov could hardly say no to Stalin. Around June 20, 1941, Timur's grave was opened and his remains were taken away. On June 22, Germany invaded the Soviet Union.

Allegedly, Timur's tomb contained at least one inscription threatening a curse upon anyone who desecrated the grave, though there's no definitive evidence that one of the most famous historical curses really existed. Still, it appears that, not long after Timur's remains were returned to Gūr-i Amīr in late 1942, the Soviets prevailed at the Battle of Stalingrad, a key engagement in the war and a point of national pride for many Russians then and today.

A British crossword accidentally published Allied code names

If you were a high-ranking Allied military officer who cracked open the Daily Telegraph in spring 1944, you had cause to be concerned. Starting that May, certain answers to the crossword aligned with code names for the upcoming D-Day invasion. Was this a plot that would somehow tip off the Germans? Could the utterly massive military operation be doomed by a crossword?

For MI5 agents, the accumulation of hints was hard to ignore. Over the course of multiple issues, the answers to the Daily Telegraph crossword included code names like Utah and Omaha (for proposed landing sites), Mulberry (a mobile harbor), Neptune (the seaborne part of the operation), and even Overlord (the code name for the whole dang operation). Surely there was a major leak or a saboteur, and they were determined to find the source.

Agents finally tracked down crossword setter Leonard Dawe, an unassuming headmaster. But instead of being a devious Nazi agent, Dawe really was a teacher who proved very surprised — and indignant. Investigators eventually concluded that Dawe had somehow managed to work in the code names innocently, perhaps because he had overheard schoolboys using the terms or directly asked them for crossword ideas. But where would British teenagers have gotten the words? It could well be that they had heard them from some rather loose-lipped Allied service members stationed nearby. Thankfully, the sloppy operational security didn't do much to imperil Operation Overlord, and D-Day proved to be a major success.

Failed chicken farmers became majorly involved in the war

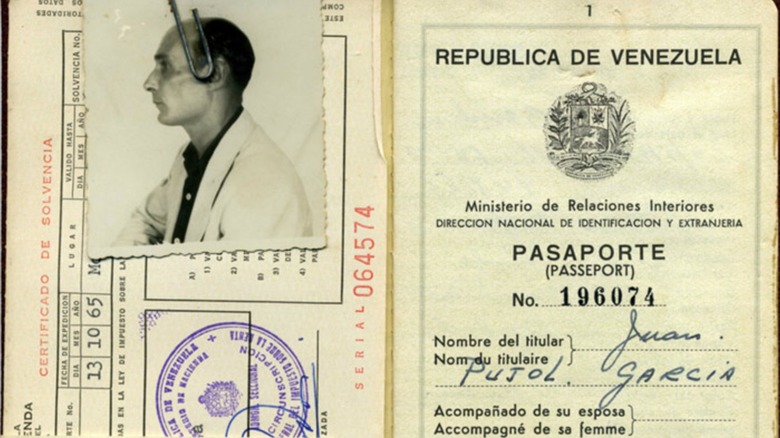

Chicken farmers are surely a largely innocuous bunch ... unless, perhaps, we're talking about chicken farmers embroiled in WWII. The first, Juan Pujol Garcia, was a Spanish self-made spy who delivered valuable intel to the Allies, though he was turned down first by the British and then the Germans (whom he hoped to double-cross). Perhaps Pujol was initially snubbed because he was a graduate of Spain's highly-regarded Royal Poultry School.

Before Heinrich Himmler became second-in-command of the Nazi regime, he was a failed chicken farmer who jumped from an unimpressive agricultural career to a now even less impressive one in politics. After the war, Himmler attempted to escape the Allies but was captured in May 1945 and died by suicide in custody. Another Nazi official, Adolf Eichmann, was also briefly captured by Allied troops, but before he could be prosecuted for his part in helping organize the Holocaust, Eichmann escaped.

For some years, he hid out in Germany under an assumed identity, taking on a number of jobs that included working as a chicken farmer. Later, he would write smugly of his time undercover, noting that he even sold eggs to British soldiers and that "no one was suspicious of the quiet little egg farmer" (via "Hiding in Plain Sight"). Yet he wasn't quite that good, as Eichmann was eventually captured by Israeli Mossad agents in 1960 near Buenos Aires, Argentina, put on trial, sentenced to death, and hanged in 1962.

Did a dice game ad really predict Pearl Harbor?

In the wake of the many confusing things about the Pearl Harbor attack, numerous factors both large and small came into consideration ... including a seemingly innocuous ad for a dice game. The game, promoted as the Deadly Double, was advertised in the New Yorker in the magazine's November 22, 1941, issue. In fact, the magazine contained multiple spots for the game, with the main ad showing the image of people playing the game in an air raid shelter — a weirdly grim tactic for Americans not yet under attack, not to mention the cover image of a kid in a Hitler mask trick-or-treating. Smaller ads in the issue showed the dice with the numbers 12 and 7. Look at a standard-issue six-sided die, and you'll see no such numbers. It certainly didn't look good just over two weeks later, when Pearl Harbor dominated the headlines.

Was this a coded message or warning connected to the impending Pearl Harbor attack? It seemed possible to investigators, who allegedly looked into the affair. Only, no one was ever arrested, no nefarious plot was uncovered, and the game's creator, Roger Paul Craig, openly mocked the notion and even later joined the Office of Strategic Services (the forebear of the CIA). Even if the numbers and the image of a family in an air raid shelter were awkward, and even if the ad kind-of, sort-of (not really) predicted Pearl Harbor, it was nothing more than coincidence.

November 9 has some eerie coincidences for Germany

While many Americans treat November 9 like any other day, in Germany it has a far heavier association and is now known as the Day of Destiny. It all starts well before WWII — the German empire crumbled that day in 1918, as the First World War came to a close. Though a republic rose in its place, the following economic and civil strife put few at ease. In 1923, an upstart Adolf Hitler chose November 9 to lead the small Nazi Party (technically the National Socialist German Workers' Party) in a revolt known as the Beer Hall Putsch. The Nazis were stopped and Hitler was thrown in jail for nine months, which pushed him to seek power through quasi-legitimate means like winning election instead of flashy but easy-to-quash rebellions.

In 1938, Hitler was firmly in power as Germany's chancellor, Nazis were annexing parts of Austria and what was then Czechoslovakia, and a wave of antisemitic laws made life all the more difficult for Jewish people in Germany and beyond. This escalated even further on November 9, with the beginning of the terrible event known as Kristallnacht (often translated as "Night of the Broken Glass") as Nazis and Nazi sympathizers broke out in violence, destroying synagogues, Jewish homes, and Jewish-owned businesses and killing at least 91 Jewish people. Some 30,000 men were also arrested and forced into concentration camps.

One man managed to be bombed in both Hiroshima and Nagasaki

One Japanese man found himself to be fully at the mercy of coincidence in August 1945. Tsutomu Yamaguchi was a naval engineer who visited the city of Hiroshima on a months-long business trip to design and construct an oil tanker. On August 6, his last day in the city, Yamaguchi was more than ready to return home. On his way to the shipyard, Yamaguchi witnessed the Enola Gay in the skies above Hiroshima and even claimed he saw a small object fall from the plane. Moments later, the bomb detonated. Yamaguchi took cover in a nearby ditch before a shockwave picked him up and deposited him in a patch of potato plants. A badly burned Yamaguchi made his way through the devastated city to the somehow still-operating train station. There, he boarded a train for his hometown of Nagasaki.

Unbelievably, a fevered, bandaged Yamaguchi went in to his office for work the morning of August 9. According to his account, Yamaguchi was in a meeting with a supervisor who didn't believe Hiroshima was gone ... when another atomic bomb went off. Yamaguchi managed to avoid major injury, though he was again dosed with radiation and had just earned the dubious distinction of surviving two atomic bomb attacks. Rushing home, he found his house partially collapsed. Yet, his wife Hisako and son Katsutoshi were both alive. Hisako had taken the baby out looking for burn ointment for her husband; the two had sheltered in a tunnel.

Coincidence brought two veterans together again

Life experiences can return to you in myriad surprising ways, but few people experience the sort of happy coincidence that came upon Lee Tulper and Ben Trujillo. Both joined the U.S. Army and served in the European theater of World War II when they were young men. Trujillo entered the infantry (and would eventually become a battlefield medic) while Tulper became a radio operator. One day, while Trujillo's unit was being moved, he spotted Tulper with his radio equipment and, his curiosity sparked by seeing a large antenna, asked the other man about his work. They exchanged only the barest information before Trujillo and his group had to move on.

For many, such a short conversation would likely be forgotten as time marched on. After all, they were going through a war, with both participating in major battles that left lasting injuries. (Tulper lost his hearing in one exchange, while Trujillo lost a leg; both earned Purple Heart medals.) But then both Tulper and Trujillo moved to Denver. Tulper was going back home to work in his family jewelry business, while Trujillo was attending watchmaking school. A supervisor asked Trujillo to source some parts, which led to him walking into none other than Tulper's store. After a short conversation, they recognized each other. But this time, instead of shrugging their shoulders and moving on, they struck up a close friendship that lasted seven decades until Trujillo's death in 2022.

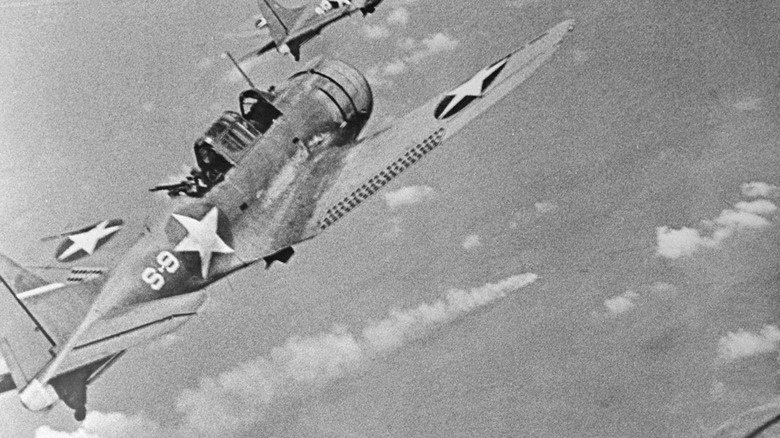

The U.S. may have won at Midway partially due to coincidence

When talking about the Allied course through the war, there's no missing the Battle of Midway, one of the most important battles of World War II. Taking place in early June 1942, the confrontation between American and Japanese forces north of Midway Atoll was a decisive turning point in the Allies' favor. With over 3,000 Japanese deaths and more than 360 American service members lost, it's clear that the battle was hard-won and hard-lost. But did coincidence play a role?

Allied attack planes launched from both the USS Enterprise and USS Yorktown aircraft carriers converged at practically the same time over the Japanese fleet. Moreover, Japanese fighter planes were off attacking other parts of the Allied fleet, leaving multiple Japanese carriers more vulnerable to the Enterprise and Yorktown strike forces. Three — the Akagi, Kaga, and Soryu — were taken down within minutes. Soon, the Hiryu aircraft carrier was irreparably damaged as well (though it first struck the Yorktown twice, contributing to the U.S. craft's eventual sinking by a Japanese submarine).

Still, it's more than worth remembering that Midway was not won by coincidence alone. During the battle, many Allied service members sacrificed it all to help win. And before the attack, American forces enjoyed a serious intelligence advantage over the Japanese, including the hard work of the U.S. Navy Combat Intelligence Unit that intercepted and then broke coded Japanese radio communications outlining Axis plans in the Pacific.

One paratrooper's chute was checked by a close family member

Surely even the most hardened paratrooper experiences a tinge of fear when they're about to fling themselves out of an airplane thousands of feet above the hard, hard ground. And if that daring feat is to be completed in wartime, with enemy troops poised to shoot? Surely, that's all the more nerve-wracking. But one WWII paratrooper, facing down just such a mission as part of the 1944 D-Day invasion into Nazi-occupied northern France, claimed no such fear. As Private Robert C. Hillman told his commanding officer in the plane, he knew that his own mother had done the final check on his parachute.

This wasn't just a case of wishful thinking undertaken by a scared young soldier (though it would be more than reasonable if Private Hillman had the jitters while flying above the English Channel on his way to parachute down behind enemy lines). He had concrete evidence on his side. Hillman's mother, Estella, worked at the Pioneer Parachute Company in his hometown of Manchester, Connecticut. A reporter on the flight heard Hillman say she was in charge of giving all parachutes leaving the facility a final inspection. As a result, her initials were on the chute, making it clear that she had deemed it safe for the military to use. Certainly, her own son took great comfort from the surprise. He made it through the invasion and returned home, dying in Meriden, Connecticut, in 1993.

Two Japanese aircraft carriers had odd parallels

When Japan struck the U.S. base at Pearl Harbor, Honolulu, in December 1941, it was in possession of one of the largest navies in the world. Though the Japanese navy would suffer considerable losses, two of its 11 aircraft carriers survived long enough to come across some odd twinned coincidences. Those were the similarly built Shōkaku and Zuikaku. Whenever the Shōkaku (Flying Crane) went into an engagement and took heavy losses, the nearby Zuikaku (Lucky Crane) would fare better, as when the Shōkaku was hit hard in the May 1942 Battle of the Coral Sea.

When the Shōkaku was damaged in the Battle of the Coral Sea, it went into port for repairs while the Zuikaku waited for its twin ship to come back into active duty. This meant that both missed the Battle of Midway, in which four Japanese carriers were damaged beyond repair. The Shōkaku was again damaged in November of that year and went back for repairs, while the Zuikaku remained relatively unscathed. The Shōkaku finally sank in June 1944 near the Mariana Islands in the Battle of the Philippine Sea. This time, the Zuikaku sustained serious damage and barely squeaked out of the engagement intact.

The Zuikaku's own demise came in the Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944. Strangely enough, it was hit by the USS Lexington CV-16, the successor to a previous carrier of the same name ... that had been sunk by aircraft launched from the Zuikaku and Shōkaku.