The Untold Truth Of Sally Ride

Sally Ride entered the history books on June 18, 1983 when, as part of the crew of Space Shuttle STS-7, she became the first American woman in space. (Two Russian cosmonauts, Valentina Tereshkova and Sventlana Savitskaya, beat her to the punch in 1963 and 1982 respectively.) Ride's job as part of the 147-hour mission was to operate a robotic arm that would help launch satellites into Earth's orbit. The trip was a glass ceiling-shattering success, and Ride, already a household name, was celebrated as a heroine and a pioneer.

Ride was, of course, more than an impressive resume in a space suit. She was a complex and very private woman who shied away from the spotlight, focusing her considerable energies on scientific discovery and progressive reform. After nine years at NASA, she would go on to a successful career as a physics professor. She also worked tirelessly as a passionate advocate for girls and women in science. Read on for more about one of the brightest stars in the history of the American space program.

Sally Ride grew up in a religious family

Sally Kristen Ride was born May 26, 1951, to Darrell Ride, a political science professor, and Carol Anderson, a volunteer counselor at a women's prison. Both Darrell and Joyce were elders in the Presbyterian church, and Ride's younger sister, Karen "Bear" Ride, would go on to become an ordained minister.

It might surprise some Ride fans and space exploration enthusiasts that one of the most famous astronauts to come out of NASA had deep roots in a faith-based community, but, according to the San Francisco Chronicle, belief in a higher power and the study of science simply went hand-in-hand for Ride and her family. Ride's sister, Bear, has a photo suggesting that Ride did not consider religion and science to be at odds with one another. One picture of the sisters shows Sally in her flight suit and Bear in her clerical collar. Another shows them in a similar pose, having traded uniforms.

In an essay published after her sister's death and excerpted by NBC News, Bear wrote that much of the credit for her and Sally's sense of wonder goes to Darrell and Carol. "Our parents encouraged us to be curious, to keep our minds and hearts open and to respect all persons as children of God. Our parents taught us to explore, and we did."

Sally Ride almost chose tennis over space

Sally Ride was very nearly not a NASA astronaut. As a young woman, she was a very strong tennis player and almost opted for that sport instead of space. According to the PostGame, Ride started taking tennis lessons at age 10 and her coach was none other than Alice Marble, a pro with four U.S. Open wins and two Wimbledon championships under her belt. Then, having received a scholarship to play tennis at LA's famed Westlake School for Girls in the late sixties, Ride was eventually ranked 18th among junior girl players in the United States and even received encouragement to remain in the sport and go pro from the legend Billie Jean King.

When Ride left Southern California for Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania, she didn't stop playing. In fact, she won the Eastern Collegiate Tennis Championships two years in a row, prompting her to return to the Golden State to pursue a career in professional tennis.

It wasn't meant to be, though. In a 2006 interview quoted on Tennis.com, Ride said she quit the sport because her forehand was weak. Her mother thought it was because Ride, a perfectionist, wasn't always able to control her game. Either way, she decided to go back to school to study English and physics. Game. Set. Match.

Sally Ride was part of the very first female class of NASA astronauts

Anyone who's read Tom Wolfe's The Right Stuff or watched Apollo 13 or Hidden Figures or First Man — in the latter case, it's right there in the title — knows that NASA began as the very definition of a boys' club. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration became a thing in 1958. Twenty years had to pass before the first women were officially admitted to the program. Sally Ride was part of that inaugural class.

The women — Judith Resnik, Anna Lee Fisher, Kathryn D. Sullivan, Margaret Rhea Seddon, and, of course, Ms. Ride — were part of NASA's Astronaut Class 8 that also included three African-American men and the program's first Asian American. As Space.com makes clear, women had previously been part of the astronaut training program — they were dubbed the Mercury 13 or the FLATs, which stood for "Fellow Lady Astronaut Trainees" — but none of those women made it into space.

Ride's class had more luck. Resnik became the first Jewish-American in space in August 1984. Sullivan became the first American woman to walk in space in October of that same year. And Fisher became the first mother in space a month later. Two words: gold stars.

Sally Ride was a classic overachiever

How's that cliche go about not having to be a rocket scientist to understand something? Well, Sally Ride was a rocket scientist. And an accomplished and decorated tennis player. And a classic overachiever who earned not one, not two, not three, but four degrees from Stanford University.

According to an article on the Stanford alumni page, Ride earned two bachelor's degrees — one in English and one in physics — as well as as a masters and PhD in physics before being accepted into the space program. That acceptance was no small feat. Ride beat out thousands of other applicants for her place in the NASA class of 1978.

Following her departure from NASA nine years later, she went back to Stanford to teach and was such a celebrity the university had to keep her name off her office door for fear she might be stalked by the public. It's bittersweet, then, that, following her death of pancreatic cancer at age 61, Stanford renamed a residence hall in her honor.

Sally Ride lived quietly as a gay woman after her time at NASA

Sally Ride, famous and beloved as she was, was largely successful at keeping the details of her personal life hidden from the public eye. In 1982, she married fellow astronaut Steve Hawley. The marriage lasted for five years, after which Ride entered into a relationship with Tam O'Shaughnessy (above), a professional tennis player and children's science writer. Ride and O'Shaughnessy remained together until Ride's death in 2012. The fact that Ride was in a partnership with a woman for most of her life shocked some friends and fans. Many learned of Ride's homosexuality for the first time when they read her obituary.

Ride's sister, Bear, also lesbian, told BuzzFeed News that Ride wasn't in the closet, per se. She was simply very private. She even kept the fact that she was suffering from pancreatic cancer from her family and friends for over a year. Bear Ride has suggested that much of her sister's reticence about her sexuality can be chalked up to their Norwegian heritage, and to the fact that Sally resisted labels. The label that seems most appropriate here is role model. And trail blazer.

Sally Ride left NASA following the Challenger disaster

On January 28, 1986, the Space Shuttle Challenger lifted off from Cape Canaveral, Florida on an uncharacteristically cold morning. The launch had been delayed for six days for various reasons, including bad weather at the Transoceanic Abort Landing site in Senegal and problems with the exterior access hatch.

According to Space.com, a long line of successful missions had made NASA complacent, and, even though at least one engineer, Allan McDonald, raised concerns that the Challenger should not be given the go-ahead — McDonald was worried that the shuttle's o-rings, rocket booster seals, would be adversely impacted by cold weather — the launch went on as planned. Seventy-three seconds after lift-off, the Challenger exploded in front of a shocked and disturbed public.

Sally Ride was the only active astronaut on the committee, the so-called Rogers Commission, that investigated the causes of the disaster. (A failed o-ring was, indeed, the culprit.) Her biographer, Lynn Sherr, told the Los Angeles Times that Ride's decision to leave NASA in 1987 was almost certainly directly linked to the Challenger tragedy and the dispiriting findings of the Rogers Commission. A member of Ride's NASA class, Judith Resnik, perished in the explosion, and Ride, one of the committee's most outspoken members, was, as the Washington Post points out, not shy about asking the hard questions. Incidentally, in 2003, after the Columbia exploded, Ride was on the investigative committee into that disaster as well.

As a female astronaut, Sally Ride suffered a lot of sexism

As the first American woman in space, Sally Ride faced often ridiculous displays of sexism. She also faced a barrage of questions from reporters, most of whom were men obviously puzzled by the sight of a female in a flight suit. According to People magazine, some of the questions Ride had to answer in NASA press conferences included, "Will the flight affect your reproductive organs?" and " Do you weep when things go wrong on the job?" and "Will you become a mother?"

Ride met such insulting questions with characteristic grace and poise. She said there was no evidence space flight rearranged a woman's reproductive organs. She wondered why reporters weren't asking her male counterparts whether or not they wept at work. And she smiled and refused to answer the third question about her plans for motherhood.

In an interview with Gloria Steinem published on the Verge, Ride said it would have been easier if another woman had joined her on her first space flight in 1983, and that the only negative experiences she had leading up to the launch and afterwards were with the press. In a History.com piece, though, she recalled biases at NASA, too. Not only did they ask her for help in designing a makeup kit that would work in space; they suggested a woman take 100 tampons with her for a one-week mission, just in case she started her period while on the shuttle.

Sally Ride worked hard to support girls in science

As a teenager, Sally Ride went to a girl's high school in Los Angeles that did very little to nurture in its students an interest in science or math. Instead, the school focused on English and sports, and Ride, who told Gloria Steinem in a 1983 interview that she suffered from the lack of STEM courses, made it her mission as a former astronaut to make sure that other young girls didn't struggle as she did to find their place in the world of science.

With that goal in mind and in collaboration with her life partner, Tam O'Shaughnessy, and UC San Diego, Ride founded Sally Ride Science, an outreach organization, in 2001. Sally Ride Science has, among other things, trained more than 30,000 students and supplied six million students with STEM books and guidance about STEM careers. The organization has also changed the national conversation about girls and science. As Space.com points out, Ride, along with O'Shaughnessy, penned five science books for children — To Space and Back, Voyager, The Third Planet, Exploring Our Solar System, and The Mystery of Mars.

According to NASA, another one of Ride's accomplishments was the EarthKAM project, which allows middle school students to take pictures of Earth from the International Space Station. During her too-short life, Ride often told young people to "reach for the stars." She enabled countless kids to do just that.

Sally Ride did not relish her fame

Sally Ride made history as the first American woman in space. She was also the youngest American in space and most likely the first gay American in space. As such, Ride's fame was a foregone conclusion. It was not something she sought, however. Ride was a very private woman and her interactions with the press prior to and after her two space missions were difficult for her. According to her Washington Post obituary, she could not have been more different from many of her fellow male astronauts in that way. Unlike John Glenn, Chuck Yeager, and Gus Grissom, she shied away from the spotlight, even going so far ask to request that NASA refuse calls for endorsing any Sally Ride-themed merchandise.

She didn't see herself as a role model or a source of inspiration and she voiced dismay that American society was still so backward that her work as an astronaut was seen as an out-of-the-norm achievement.

In 1987, after Ride's work on the Roger's Commission — the committee charged with investigating the causes of the Challenger explosion — she left NASA to pursue a career as a physics professor, first at Stanford and later at University of California, San Diego. The San Diego Tribune described Ride as a "trail-blazing but down-to-earth" astronaut, quoting her life partner, Tam O'Shaughnessy as saying, "Sally is someone who did things because she wanted to do them, not for any awards or statues."

The Sally Ride soundtrack

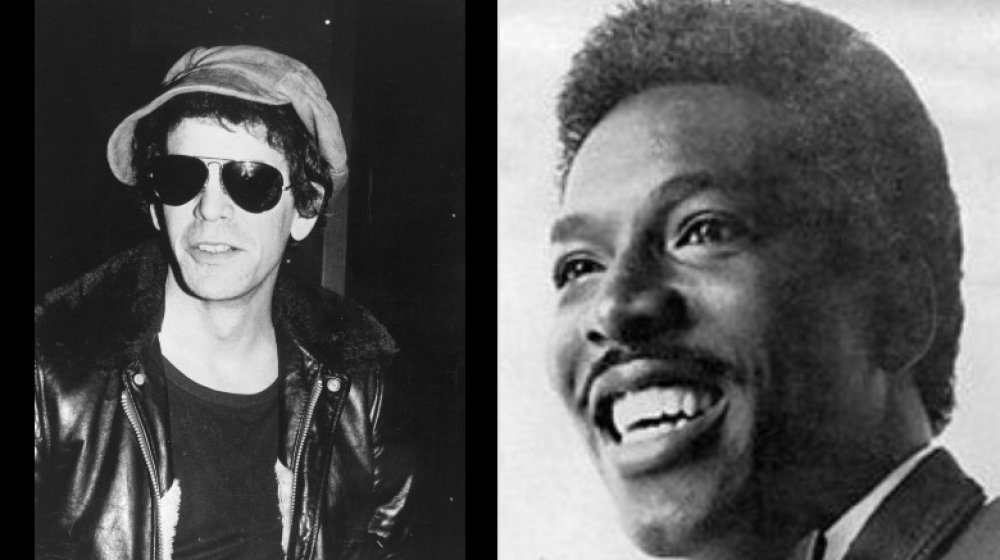

Leading up to Sally Ride's first mission in space in June 1983, radio stations around America played Wilson Pickett's recording of "Mustang Sally" on repeat. The song, written in 1965 by R&B artist Mack Rice, was a natural pick for DJs that summer because it includes the lyrics "ride, Sally, ride," and excited spectators serenaded Ride with it while she climbed into the shuttle with her four crewmates.

Sally Ride's connection to American popular culture doesn't end there. Lou Reed of Velvet Underground wrote a song called "Ride Sally Ride," reportedly before he'd heard of the soon-to-be famous astronaut. A New Yorker writer considered Reed's song, which Reed wrote in 1974 and included on his album, Sally Can't Ride, an eerily accurate prediction of Ride's ascension in NASA. As proof, the writer cited these lyrics: "Ooh, isn't it nice when your heart is made of ice?," arguing that the line can easily be read as a prophetic reference to Ride's trademark cool.

Of course, both "Mustang Sally" and "Ride Sally Ride" were written before Sally Ride even joined the space program. And the coincidence is easy to explain away, given the fact that "Sally" is a standard American girl name and "Ride" is a verb. Still, it's a testament to Ride's popularity and the far-reaching impact of her work that music fans' minds automatically turn to her when they hear those now famous three little words.

Sally Ride made a shuttle ride more comfortable for her sisters

When Sally Ride was accepted into the NASA space program in 1978, the shuttles were designed for men. For the first 25 years of American space flight, that sufficed. Then Ride came along and changed everything. Well, she changed some pretty key things. Prior to leaving NASA in 1987, Ride made sure, according to the Washington Post, to leave her mark on space shuttle design and to do so in a way that would benefit the female astronauts that came after her. And no, these changes did not involve makeup kits or tampons. They involved comfort. She saw to it that engineers made the shuttle seats adjustable to more easily accommodate a woman. And she asked that they add a curtain to the restroom area and redesign the vacuum toilet.

Adjustable seats, privacy curtains, and a more comfortable toilet might seem like small potatoes when one is pondering a) the vastness of space and b) the immense challenges that come with confronting inequality in the workplace, but hey, one small step often leads to a giant leap. And Ride took both.

Sally Ride's last battle was with pancreatic cancer

In her sixty-one years, Sally Ride fought many battles. Her first fights were on the tennis court, where, more often than not, she emerged victorious. Later, she fought for equal standing in America's space program. She won that battle, too, making history as the first American woman in space. Still later, she worked hard to see to it that young people interested in science — girls, especially — had the tools and books and guidance they needed to aid them in their studies.

Her final battle was one she could not win. In 2010, she was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Seventeen months later, she died, having only recently told her family and friends about her illness. According to CNN, President Barack Obama marked Ride's passing by saying that her life was proof that there are no limits to what humans can achieve.

Four years prior to her death, in an interview with the cable TV network, Ride talked about how awe-inspiring it was to view Earth from the window of the space shuttle. "It's just remarkable how beautiful our planet is and how fragile it looks," she said. How fragile, too, are the humans that inhabit it. Even tough-as-nails trailblazers and glass ceiling shatterers. Ride, Sally, ride. To the stars and into the sunset.