The Mysterious Stone Archeologists Reburied To Protect From People

Every now and then, humanity gets a reminder of how little it knows about its own remote past. Sites like Stonehenge in Salisbury, England — with central pillars dating to about 2500 B.C.E. — sit at the top of memorable global locations that still intrigue and invite speculation. But an ancient temple site like Gobekli Tepe in Turkey proves truly mystifying, as it dates to about 9000 B.C.E. That's further in the past from Stonehenge than we are from Stonehenge in the present. Some structures or objects seem religious in nature, while others are devoted to astronomy or sheer artistry. And some, like the Cochno Stone, need to be protected. Not from the elements, but from us.

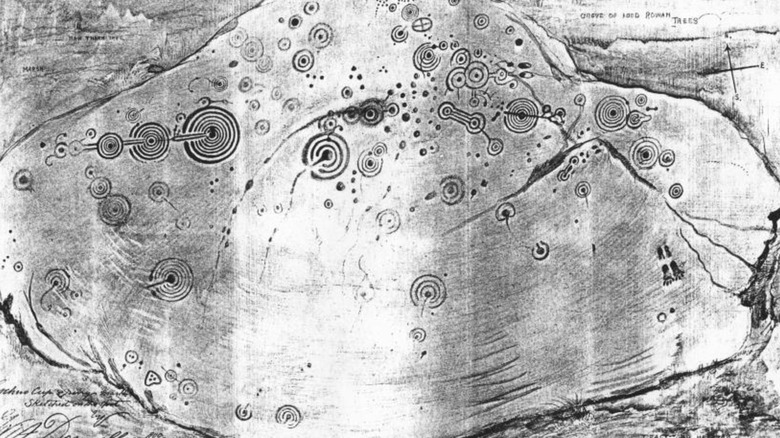

Dating back to about 3000 B.C.E. and accidentally discovered in 1887 in the town of Clydebank, Scotland, near Glasgow, the Cochno Stone was dubbed the "most important Neolithic cup and ring marked rock art panel in Europe," per the University of Glasgow. What does "cup and ring marked" mean, visually? It means that the Cochno Stone is a smooth slab engraved with rings and lines that look like crop circle formations.

In 2016, the stone was unearthed for the first time since it was first covered up in 1965. So why was this artifact buried and then reburied? Well, because people are idiots and jerks — shocking, we know. The stone was vandalized, even by those setting out to investigate it. At present, the stone remains buried. Researchers are examining it thanks to 3D imaging technology.

A 5000-year-old mystery inscribed in stone

Even before Reverend James Harvey came across the Cochno Stone in 1887, local shepherds had known about it for quite some time. Deriving its Anglicized name from the Gaelic "Cauchanach" — "place of little cups" — its name refers to the cup-and-ring shaped markings on its surface. Attributed to "ancient rock-engravers" in the area of Scotland west of Glasgow, Harvey wrote, "It is my hope that, in the course of time, with a little labour, more of these mysterious hieroglyphs may be brought again to the light of day." That quote comes from a proposal from archaeologist Kenneth Brophy of the University of Glasgow to Historic Scotland for the use of digital imaging technology under the Factum Foundation to investigate the Cochno Stone.

Located near a quarry, the Cochno Stone is a soft slab of sandstone — soft enough to carve into more easily than other stone. Much like other ancient objects, structures, and sites, some have attributed astronomical meaning to its Cochno Stone inscriptions. The aforementioned proposal suggests that the inscriptions are "the first 'sprouts' of language, pre-syntax," abstractified into geometric pictures. But really, no one knows what it means, who made it, or anything else.

Folks have tried to make sense of the Cochno Stone, and that's where the vandalism started. Ludovic Mann, known for "unorthodox 'mythocelestial'" interpretations of the Cochno Stone (per the proposal), painted over the stone's lines in 1937 — oil paint, too — to try and see them better. While standing on it, of course. The stone was subjected to further, random etchings by passersby, and Clydebank residents had to bury it in 1965 to protect it.

Buried to protect it, then unearthed, then reburied

As the proposal to the Factum Foundation reads, the Cochno Stone was buried "to prevent any further degradation as a result of neglect and damage from graffiti." "Graffiti" in this case doesn't mean spray paint — it means any kind of writing on a surface, kind of like how some thoughtless individuals carve their names into the Colosseum in Rome. Since 1965, the Cochno Stone has sat under soil and mud, sadly uninvestigated considering its historic and cultural importance.

Come 2016, this changed thanks to the efforts of archaeologist Kenneth Brophy of the University of Glasgow, his team, and the Factum Foundation. As an archaeological dig video from the University of Glasgow shows and explains, a team uncovered the Cochno Stone for the purpose of viewing it, yes, but more for imaging purposes. The team used drones to take photos of the stone and then software to make a model — a facsimile — of the stone for later investigation. The Factum Foundation has done a number of similar facsimile projects in the past — hence the proposal we talked about earlier.

After finishing their work, Brophy's team reburied the stone to preserve it once again. "It is emotional when you have worked on a project such as this, touched it, walked on it and closely examined it, to then rebury it but for now that is what we have to do to protect it from the elements," the University of Glasgow quotes him. There's no further word yet on the facsimile, but the stone remains safe, untouched, and out of sight.