Rules That Jesus Actually Broke In The Bible

In Matthew 5, as Jesus Christ begins his famous Sermon on the Mount, he tells the assembled crowd: "Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them." After this assurance, he launches into his famous admonitions about loving one's enemies and turning the other cheek. In the same section of the sermon, he warns against swearing oaths, divorcing wives, and making offerings to the Lord before reconciling one's self to estranged siblings — all points made in contrast to edicts from the Old Testament, the "law and the prophets" Jesus claimed he was coming to fulfil.

Later on, in the New Testament book Hebrews, it is written: "The law is only a shadow of the good things that are coming — not the realities themselves. For this reason it can never, by the same sacrifices repeated endlessly year after year, make perfect those who draw near to worship." This has been interpreted as meaning that the ceremonial sacrifices long practiced by the Israelites were only a temporary necessity, able to be set aside once the messiah came. And calls to "turn the other cheek" may be thought of less as total pacifism than as savvy, nonviolent protest.

But the details of this interpretation didn't patch over the tensions between followers of Jesus and the Pharisees, which is evident in the New Testament's gospels. Nor did they paper over all the times Jesus seems to explicitly contradict laws and beliefs from the Old Testament. Here are a few of those instances and how they've been addressed within Christianity.

No touching lepers

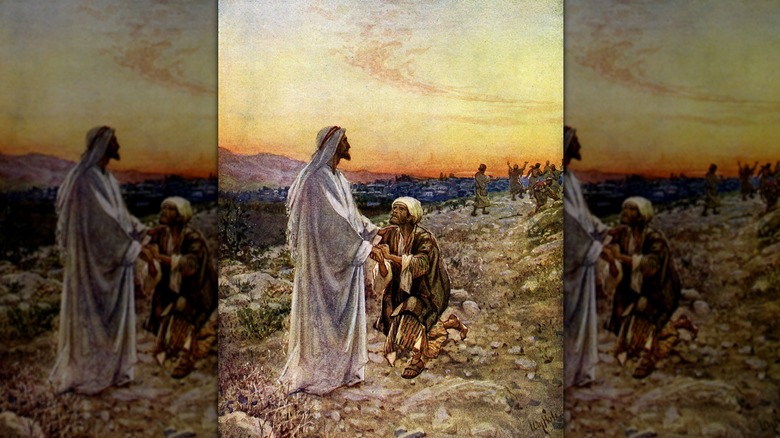

Leprosy is among the oldest and most notorious diseases in human history. The infected have visible marks, and this has led to them being singled out, leading many to consider their illness a punishment from God. They were the "unclean," outcasts from society, isolated lest their pestilence spread. Half of the Old Testament's Leviticus 14 is dedicated to prescribed rituals for the cleansing of lepers and others marked by skin diseases, and it's taken for granted in those prescriptions that only duly anointed priests can safely touch lepers as part of the ceremonies.

The term "rabbi" would have applied to Jesus in his day, but he was not an ordained priest. So his healing of lepers, as recounted in Matthew, Luke, and Mark, has been taken as a violation of religious law. For this reason, some argue he cannot be a divine presence. Yet Christians have argued that the warnings of "unclean" lepers were meant to protect others from disease, not shame and degrade the afflicted. In this interpretation, Jesus worked around the letter of the law to fulfil its spirit by providing cures. But throughout the Gospels, Jesus calls for his followers to fully heed God's laws, with no words for loopholes or ambiguities.

Apologetics Press argues that Jesus obeyed the letter and the spirit of the law when he touched the lepers to heal them. Jesus, they say, was a priest, the highest priest as God on Earth. Furthermore, they argue that uncleanliness through illnesses like leprosy was not, under Jewish religious law, regarded as inherently sinful.

No working on the Sabbath

Jesus has a complicated relationship with the Pharisees, a legalistic sect of Judaism. At times, the Pharisees seem friendly to Jesus, or at least respectful. They warned him of a threat from Herod, and some protect the early Christians after the Resurrection. But the Pharisees also act as a recurring foil for Jesus in the Gospels, challenging his actions and accusing him of violating the law.

Jesus and the Pharisees clash multiple times over the Sabbath — specifically, whether he breaks the law by healing on the holy day. Jesus heals during the religious observance many times, and these public miracles (in Matthew 12, Mark 3, John 5, John 9, and Luke 13) all brought upon him question and rebuke. By the first century, the idea of the Sabbath had evolved from a day to rest from labor and offer worship to God to a rigidly enforced abstention from almost any activity at all, at least under the Pharisees' interpretation. To go about healing the sick on the Sabbath was, by their creed, a violation of the edict to rest and worship.

Jesus answered the Pharisees in various ways. In Luke 13, he notes that they are unwilling to see the sick healed but will take their livestock to watering holes. In Mark 3, he rhetorically asks whether one should do good or evil — in other words, heal the sick or let them die — on the Lord's day. And in the prior chapter, he notes: "The Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath."

No drinking blood

The Old Testament isn't too keen on consuming blood. In Genesis 9, God himself forbids eating anything that still has its life's blood in its veins, and Leviticus and Deuteronomy have several prohibitions against eating or drinking the body fluid. That's all Leviticus 17 is about, with God threatening to set himself against any blood-drinker out there. The reason for this prohibition? "The blood is the life."

It's just a little strange, then, to have the central ritual of Christianity concerned with eating the flesh and drinking the blood of the messiah. Whether the bread and wine used in Mass are symbolic or undergo transubstantiation is an old and ongoing difference of belief among Christian denominations with a long history of controversy. But even a metaphorical consumption of blood seems like a pretty wild departure from the repeated injunctions against it in the Old Testament. Even Catholic priests have conceded that defending the ritual, and their belief in transubstantiation, is a tall order.

Jesus's declaration in Mark 7 that all foods are clean gets around the issue for some, but there are still prohibitions against blood-drinking elsewhere in the New Testament after the Resurrection. Catholicism points to Jesus' words from John 6 for the answer: "Unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you have no life in you." As discussed on Catholic Answers, this is believed to supersede past injunctions and represent an aspect of "positive divine law" — that which can be changed by God.

No talking to women unsupervised

As outlined on Franciscan Media, among the prayers offered by Jewish men in the first century was: "Praised be God that he has not created me a woman." That should give you some idea of how patriarchal the Israeli community of Jesus' time was. Women and girls were highly vulnerable in this society, being almost entirely reliant on their male relations. They enjoyed no rights to property or wealth, had no legal means to remove themselves from a marriage for any reason, and were shut out of religious life. While there was no ironclad law against a man speaking to a woman without the supervision of her father or husband, it was a strong taboo.

Jesus violates that taboo several times throughout the Gospels. That he did so surprised even the women he interacted with. The Samaritan woman he asks for water in John 4 wonders why Jesus would speak with her, considering she is both a woman and a foreigner. His disciples are surprised too, though none of them voices their concerns. In Luke 8, Jesus is compassionate toward a woman who touches him to be healed without asking. And in Luke 13, after he is attacked for healing a woman on the Sabbath, he declares her a "daughter of Abraham." For the first time ever, he granted Jewish women equal status and respect as the "sons of Abraham," as Jewish men had long been known as.