The Only 5 Times In History Inmates Refused Clemency From Presidents

It came as a surprise on December 12, 2024, when President Joe Biden commuted the prison sentences of a whopping 1,499 people. This included reducing the sentences of 37 inmates on death row to life in prison. He also pardoned 39 other individuals. In the end, Biden's act of clemency was the largest single such act in presidential history, far above President Obama's previous all-time high of 330 in 2017. Such end-of-term clemency bonanzas aren't uncommon, at least since President Ford (1974 to 1977), though they've skyrocketed dramatically since George Bush, Sr.'s presidency (1989 to 1993).

We mentioned that 37 of Biden's commutations — reductions in sentencing — involved inmates on death row. That's 37 out of the 40 inmates on federal death row, leaving only three people awaiting execution. Two of those are on death row for mass shootings at houses of worship, the other is the person convicted of the Boston Marathon bombing. Those with commuted sentences — every single one — also killed people, in one instance, an entire family. "I condemn these murderers, grieve for the victims of their despicable acts," the White House quotes Biden. Nonetheless, his administration has imposed a ban on federal executions, "in cases other than terrorism and hate-motivated mass murder."

Surprisingly, two of those 37 people are refusing Biden's commutation: Shannon Wayne Agofsky and Len Davis. But before the reader assumes that they're refusing out of contrition, The Washington Post says that they're holding out for appeals. They're not the first people to refuse a presidential act of clemency. They are, however, only two of five people out of the United States' nearly 250-year history to do so.

George Wilson refused Andrew Jackson's pardon

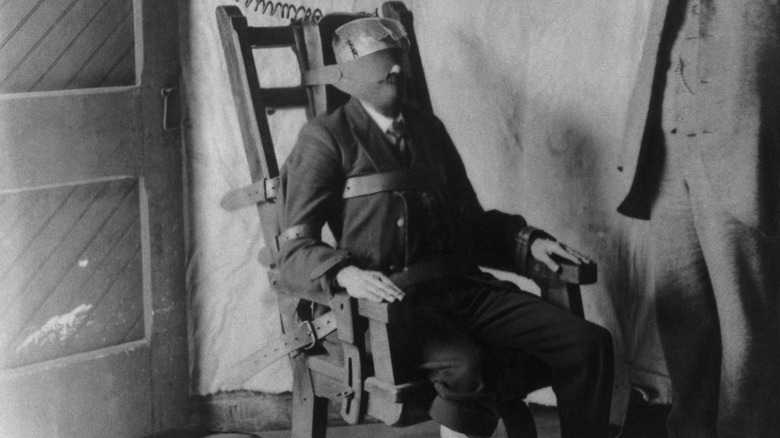

The first instance of a criminal refusing presidential clemency came in 1830 when Andrew Jackson was president. The United States was a very different place at the time, consisting of 24 states, four territories, and execution largely by hanging. In 1830, when Jackson pardoned George Wilson, 36 people were hanged to death and one was killed by firing squad.

Wilson and his co-criminal, James Porter, had committed a crime that might not seem like it warrants the death penalty: robbing mailmen of mail. They did this six times in November and December 1829, were apprehended, went to trial, and pleaded "not guilty" in April 1930. On May 27, they were sentenced to death for "feloniously, violently" robbing and assaulting mail carrier Samuel McCrea and putting the man's life at risk, as Justia quotes. On July 2, Porter became one of the 37 people executed that year.

Wilson, however, withdrew his plea of not guilty. President Jackson, in turn, pardoned Wilson's mail-stealing crimes provided that Wilson serve 20 years for other crimes that he'd committed. Strangely enough, Wilson refused; it's suggested he mixed up what he was being pardoned for. As Justia says, Wilson's refusal established a legal precedent described by the Supreme Court in 1833's United States v. Wilson: "A pardon is a deed to the validity of which delivery is essential, and delivery is not complete without acceptance. It may then be rejected by the person to whom it is tendered, and if it be rejected, we have discovered no power in a court to force it on him."

George Burdick refused Woodrow Wilson's pardon

It was a long time before anyone else refused an act of presidential clemency — 85 years, in fact, during the presidency of Woodrow Wilson in 1915. The case is a strange one, as it doesn't involve what you'd typically expect of a prison sentence worth pardoning or commuting, i.e., murders and death sentences. It involved a case of suspected fraud, the invocation of Fifth Amendment rights, and Wilson reaching out with a pardon before anyone was charged with anything.

In a nutshell, the case involved an editor for the New York Tribune, George Burdick, refusing to answer questions to a grand jury regarding crimes that he "may have committed," per Constitution Annotated. Those crimes were related to customs fraud, which might involve undervaluing an imported product, for instance. Burdick cited the Fifth Amendment to avoid answering, stating that his answers might incriminate himself, and President Wilson intervened and pardoned him. This was an odd move because Burdick hadn't even been charged with anything. Burdick, apparently an extremely stubborn person, refused the pardon and then continued refusing to answer the jury's questions.

The case was something of a touchstone when it comes to presidential power and the limits of pardons. It further defined what a pardon is, and demonstrated that even a presidential pardon can't override an amendment in the U.S. Constitution. In other words, "it was Burdick's right to refuse it [the pardon]," because he wanted to exercise his Fifth Amendment powers, per Constitution Annotated.

Vuco Perovich objected to Wiliam Taft's commutation

The next time someone refused a presidential act of clemency came in 1927. Or we should say "objected to" an act of presidential clemency, because the criminal in question — Vuco Perovich — complained to no avail. Perovich's case is messy and not clear-cut or standard in any way. In the end, it helped distinguish between the refusal of a pardon vs. the refusal of a commutation of sentence.

Perovich had been sentenced to death in 1905 for murder. He sat on death row for four years until President William Howard Taft commuted his sentence to life in prison in 1909. This wasn't a highly selective choice on Taft's part, but part of a series of regular acts of mercy enacted by the president at the time. Thus began Perovich's odyssey from prison to prison, leaving Alaska to go to Washington, and eventually ending up in Leavenworth, Kansas. In 1918, perhaps growing tired of being shuffled around, Perovich asked for a pardon. He was refused, tried again in 1921, and was refused again. Then in 1925, he protested his sentence being commuted altogether, filing a writ of habeus corpus meant to question whether he was being detained on lawful grounds. It's unclear whether or not Perovich preferred to go back to death row, but this was perhaps the case.

Ultimately, in 1927 the Supreme Court ruled that the, "president may commute a sentence of death to life imprisonment without the convict's consent," per Justia. This ruling impacts cases all the way to the present, including President Biden's recent acts of clemency.

Shannon Agofsky filed an injunction against Joe Biden's commutation

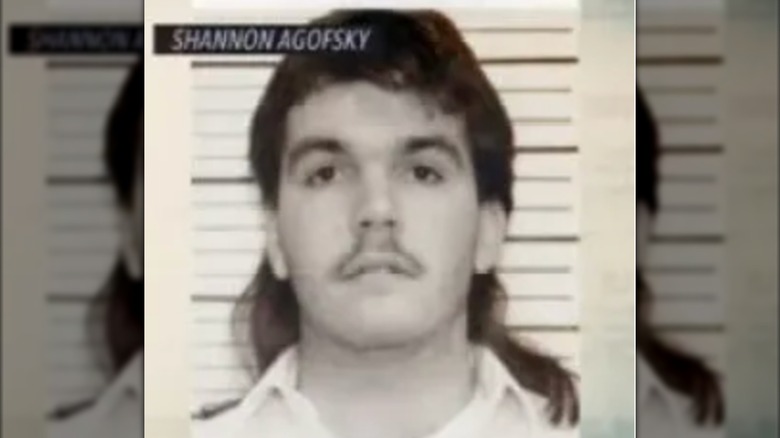

At this point we can see: 1) No two refusals of clemency are alike, 2) Each case built on the precedent of earlier cases, and, 3) Refusals of clemency are rare things, indeed. This is why it's so strange that not only one, but two individuals, refused President Joe Biden's recent, December 2024 act of clemency. One of these individuals, Shannon Agofsky, was even featured on shows like Oxygen's "Killer Siblings."

Back in 1989, Shannon and his brother Joe robbed about $71,500 from a bank in Noel, Missouri. The bank manager went missing, too, and was found floating in a river with a chain hoist duct-taped to his ankle. Evidence couldn't 100% connect his death to the Agofsky brothers, but the brothers were found guilty of aggravated armed bank robbery, conspiracy, and use of a firearm while committing a felony. They were sentenced to life in prison. Joe died in incarceration from unknown causes in 2013, and Shannon received the death sentence in 2004 for the 2001 murder of a fellow inmate.

Per NBC News, Shannon filed an injunction against Biden's attempt to commute his sentence back to life behind bars. "The defendant never requested commutation. The defendant never filed for commutation," the injunction reads. "To commute his sentence now, while the defendant has active litigation in court, is to strip him of the protection of heightened scrutiny." The "active litigation" in question refers to both Shannon's original 1989 bank robbery case and "how he was charged with murder" when he stomped a man to death in prison in 2001.

Len Davis rejected Joe Biden's commutation

Len Davis is the fifth and final person who's refused an act of clemency from a U.S. president. Like Shannon Agofsky, Davis protested having his sentence commuted from death to life to prison. He's also, like Agofsky, an inmate at the United States Penitentiary, Terre Haute, in Indiana. They also both filed their injunctions on the same day, December 30, 2024. But, the confirmed facts of Davis' case stand out as particularly disturbing.

Davis operated in the Desire Projects in New Orleans in the 1990s as a police officer. According to Human Rights Watch, he was known by various nicknames like the "Desire Terrorist" and "Robocop." There'd been complaints of brutality about Davis going back to 1987, usually related to intimidation and violence, and he was eventually sentenced to death for hiring a hitman to kill a mother of three named Kim Groves in 1994 in retaliation for filing a brutality complaint against him. Not only was he convicted and sentenced to death in 1996 for ordering Groves' murder, he was convicted on separate charges related to involvement in a cocaine trafficking ring, for which he received another life sentence, plus five years. He also provided fake information that led to three false arrests, amongst other things.

Per Police1, Davis protested Biden's commutation because the president was "forcing an unconstitutional life sentence" on him. Echoing Agofsky's rationale, his motion reads, "Prisoner Davis did not request any commutation nor does he accept any commutation." Furthermore, his motion says that he, "always maintained his innocence and argued that the federal court had no jurisdiction to try him for civil rights offenses."