The Life Of Typhoid Mary Was Worse Than You Thought

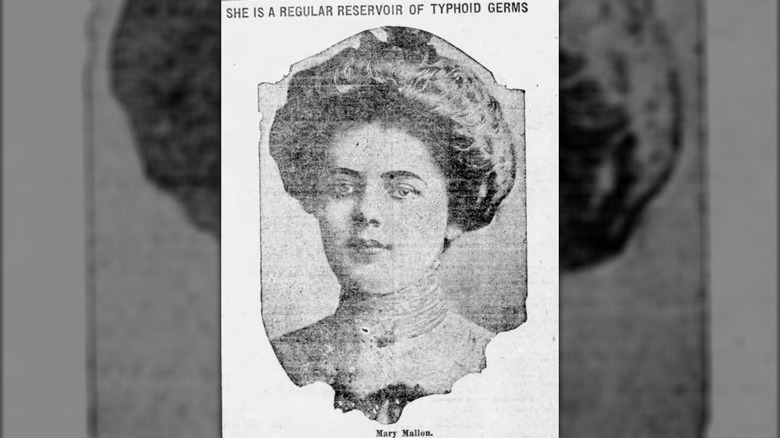

Typhoid fever is a terrible disease with a messed-up history. Spread by water or food contaminated with fecal matter, symptoms include high fever, nausea, and diarrhea. Even in modern times typhoid fever can be fatal, and in the early 20th century often was. Therefore typhoid fever is definitely not the kind of thing you would want your name to be synonymous with. Unfortunately for Mary Mallon, she went from an anonymous working-class New Yorker to the infamous "Typhoid Mary." The discovery that she was making people sick with typhoid despite not being sick herself solved a medical mystery and changed everything scientists knew. However, to a medically ignorant public who read sensationalized tales in the press, she was one of the most feared women in the U.S.

The story of "Typhoid Mary" is incredibly tragic, but the life of the real Mary Mallon is far worse than any yellow journalism could make it seem. It was a personal tragedy that affected every day of her life for over two and a half decades. She wasn't just some diseased boogeyman, she was a real person who found herself in a horrible situation with no way out. Here's why the life of "Typhoid Mary" was worse than you thought.

She immigrated on her own to the U.S. as a teenager

Mary Mallon left poverty in Ireland in the quintessential American immigrant narrative. This was decades after the potato famine of the 1840s, but the Irish were still coming to America in droves in the 1880s. Amazingly, Mallon was a teenager (sources disagree on whether she was 15 or 17 years old when she made the journey from Cookstown, Ireland, pictured above) when she crossed the Atlantic, leaving her home behind forever and all by herself, too. While the basics of her story were the same as millions in her position, Mallon's journey was not exactly like the stereotypical image many might have of immigrating to New York City at that time. When she arrived in 1883, the Statue of Liberty was not built yet: Ellis Island wouldn't open for nine more years.

Mallon would have been poor, scrambling, and discriminated against when she got to New York City. Fortunately, her aunt and uncle arrived before her and she was able to live with them. It's possible she was one of the tens of thousands of poor Irish whose journey was paid for by charity or by family members already in the U.S. The year before Mallon landed, the U.K. Parliament (then in control of the entire country of Ireland) voted for legislation to cover the travel costs of 54,000 Irish immigrants to America.

For all of the difficulties coming to the U.S. alone as a teenager entailed, Mallon had one piece of luck. She got a good job — as a cook.

Mary Mallon was not knowingly making people sick

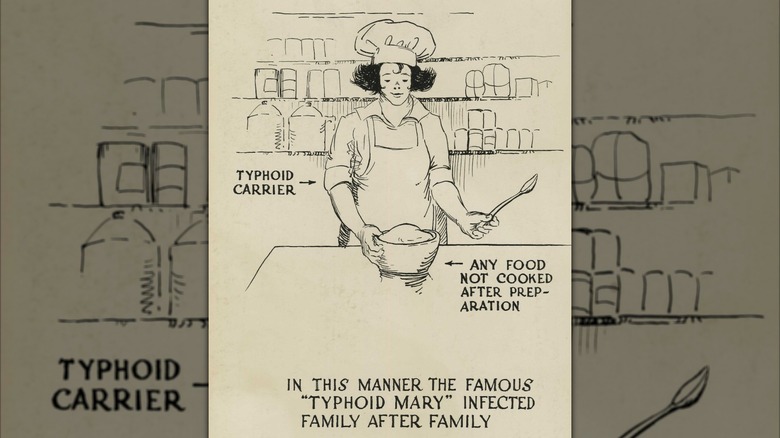

When Mary Mallon started infecting her employers and their families with typhoid by handling the food she prepared for them, she wasn't doing it knowingly. Germ theory was new; it had only been proved in the mid-1800s and even surgeons were ignoring the reality that germ theory presented until the turn of the 20th century. As for the public, they knew even less about it, let alone an uneducated immigrant woman like Mallon.

So imagine you are in her shoes. As far as you know, you have never had typhoid, or at least certainly not a bad case. Suddenly a stranger shows up at your place of employment, telling you that you are spreading a disease you don't have and that you are killing people. Also, he wants a sample of your poop. You would be well within your rights to chase that man out of the house with a knife, as Mallon did.

Perhaps because of her ignorance of cutting-edge medical science or perhaps just because she did not like the people trying to educate her, Mallon continued to insist she could not be making others sick. She filed a lawsuit seeking $50,000 in 1911 in which she insisted she could prove she was not a typhoid carrier. In 1909, a reporter alleged Mallon told them that every time her stool was examined by the Health Department, she always sent a sample to an outside lab, which had failed to find any typhoid bacilli.

She was held without charge

Despite a key investigator, Dr. George Soper, finding conclusive evidence connecting Mary Mallon to various typhoid outbreaks in the homes where she was a cook, she was never actually charged with any crime, let alone convicted of one; accidentlly making people sick because you don't wash your hands well enough would be a tough one to prosecute. While it is tragic that some connected with her got sick and died, legally she was not responsible.

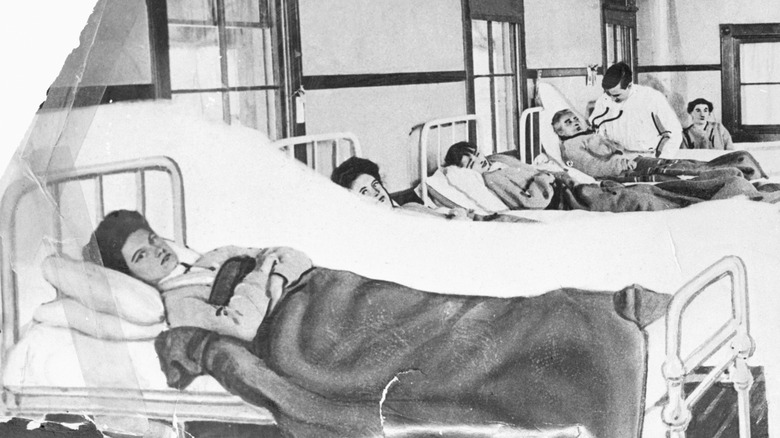

Despite this, she was held against her will for a total of 26 years. Her first confinement on North Brother Island (used to quarantine others with infectious diseases) in New York's East River began in 1907. At this point, no healthy carriers had ever been discovered, so the scientists and judges involved could believe they were doing this for good reasons, to allow them to study her. Mallon had refused to peacefully submit to being a lab rat for something she could not understand. She refused to allow anyone to take samples of her blood and stool, and reacted aggressively to attempts to do so. The authority's solution was to effectively lock her up.

Mallon had no idea how long she would be held. She was given a small bungalow to live in and assisted the doctors and nurses on the island, but it was a hellish life with little to do but sit and think about how she was there against her will. She was confined to the island from 1907 to 1910, and again from 1915 until her death in 1938.

She was the only asymptomatic carrier to be imprisoned

While her name has gone down in history in connection with spreading disease, Mary Mallon was not a particularly special medical case. The thing that made her notable was the discovery by Dr. George Soper that her case was the first time a person had been found to be a healthy carrier of typhoid — someone who was not sick themselves but still harbored typhoid germs. The medical community had a theory this was possible for years, but it was only when Dr. Soper presented his findings about Mallon to the Biological Society of Washington, D.C., in 1907 that it was proven.

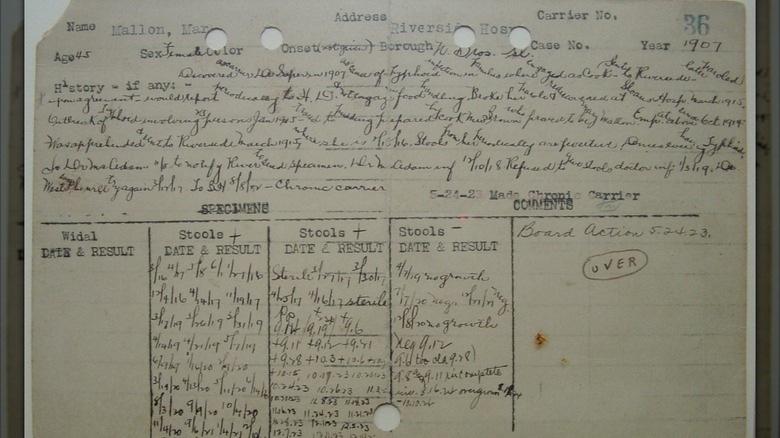

Dr. Soper took samples of Mallon's stool and found typhoid bacillus present (pictured are records of these results over the course of her long confinement). Based on this alone, Mallon found herself stripped of her liberty.

Mallon was not notable as a seemingly healthy carrier of typhoid — an estimated 6,000-9,000 new people became asymptomatic carriers every year in the U.S. at that time, and the medical community was aware of this even then. Yet, for some reason, Mallon was the only one ever incarcerated. Others, once discovered, might be required to register with a local health department, get periodic checkups, and be encouraged to avoid handling other people's food. But even as this became the standard way to handle the increasing number of healthy carriers of this deadly disease, Mallon continued to be held against her will for decades.

Her freedom relied on her taking low-paying jobs

In 1909, Mary Mallon went all the way to the New York Supreme Court in an attempt to gain her freedom, but was denied. The following year, she finally had a bit of luck. The hospital on North Brother Island got a new administrator who agreed to help her get out of there. There was just one catch: since she could still make people sick by handling their food, Mallon had to promise she would never get a job as a cook again.

This was a bigger ask than it might seem, and Mallon refused, despite this extending her time being held without charge. For an Irish immigrant in her position, it was the best possible job she could get, dignified with decent pay. If she agreed to never work with food again, she would have to take harder, lower-paying jobs. And that was assuming she could manage to do so without anyone associating her with the by-then-infamous "Typhoid Mary" moniker. Employers probably didn't understand germ theory either, and would only know that she made people sick by being around them.

Mallon did work as a laundress for a short time, but two years after she gained her freedom, she disappeared. In 1915, after an outbreak of typhoid, she was discovered to be working as a cook again. While still not charged with a crime, the fact she broke her non-legally binding promise meant she was sent back to involuntary quarantine until she died.

She was understandably furious about what happened to her

Mary Mallon was filled with rage over her treatment by the health department and legal system. She had been a law-abiding, employed member of the community and then some scientists decided she needed to be locked up for the rest of her life. Few would stand for it, and Mallon expressed her frustration any way she could.

She got a lawyer and took her case all the way to the New York Supreme Court. In her handwritten affidavit for the case, there is visual proof of her emotional state: as she fills more pages, the handwriting goes from perfect penmanship to very sloppy, and the tone of the contents becomes much angrier. She also launched a suit against the health department seeking $50,000 in damages. She wrote threatening letters to the doctors who helped put and keep her in quarantine on North Brother Island.

Those who lived and worked with Mallon on the island knew better than to call her "Typhoid Mary," and most were smart enough to avoid talking about that disease around her at all. Allegedly, she would get aggressive if anyone forgot and let something about typhoid slip out. When Mallon agreed not to take a job as a cook in order to secure her release in 1910, the document she signed had a few words added in her own hand, making clear she did not accept responsibility for what the doctors were accusing her of.

She couldn't walk for the last six years of her life

The second time Mary Mallon was confined to the hospital on North Brother Island (pictured above in its current dilapidated state) in 1915, she was about 45 years old. She was kept there until the day she died in 1938, aged around 68 or 69. By this point, any danger she posed to the public had been lessened considerably, since even if she was released, her health meant she would not have been able to hold down a job as a cook for many years at that point.

Some historians think Mallon may have had a minor stroke at some point that went unnoticed. There is at least one image of her with a slightly drooping mouth that could be evidence for this theory. What is not in doubt is that she had a much larger stroke on Christmas Day in 1932. She was found on the floor by a porter, totally immobile. The stroke had paralyzed her, and she would not walk again in the six remaining years before she died.

Despite her paralysis — which meant she couldn't stand in a kitchen making food for an employer even if she wanted to — Mallon was still not released from her confinement. She was simply moved from her private bungalow to the hospital building to be looked after. As the end of her life neared, she was never transferred to a hospital off the island or asked where she would like to be moved to.

Her funeral lacked any dignity

Mary Mallon died in the hospital on North Brother Island on November 11, 1938, having never regained her freedom. By that point, she was disabled, a shadow of her former self, and resigned to the fact she was going to die in forced isolation. She was said to have become more religious over the years as a way of dealing with her fate. She had remained an intensely private person and shared very few personal details with others. To the end, she insisted that she could not be making others sick since she was healthy.

Those who had controlled her life were not done disrespecting her yet. There are conflicting reports on whether or not an autopsy was performed, and it may be that the original reports saying none was done were only to reassure the public. Officially, she died from a week-long case of pneumonia, and some sources say she was cremated.

Mallon's remains were hurriedly buried the same day she died. A funeral service at St. Luke's Catholic Church in the Bronx drew nine anonymous mourners, although none of the healthcare workers (the only people other than the quarantined individuals she had been in contact with for decades) were said to have bothered to attend. No mourners escorted her coffin to St. Raymond's Cemetery, where she was buried. Her tombstone (pictured), which she may have paid for herself, records Mallon by her real name and not the nickname she hated.

She didn't get to tell her story - her nemesis did

Mary Mallon was not the only famous historical figure who was quarantined when it was discovered they were spreading disease, but she was treated particularly unjustly. Much of the blame for this lies at the feet of Dr. George Soper, the man who would become her nemesis. Dr. Soper discovered Mallon was a typhoid carrier and spent his career trying to keep her imprisoned, and also built his fame off her story.

Dr. Soper told his version of her story many times and at length. Over the years, his tale got more dramatic and more unfair to Mallon. He also refused to acknowledge she had any right to be angry, insisting that if she had just done what he asked everything would have turned out okay. He made it clear that, in his opinion, she was too loud, opinionated, and obstinate, called attention to her size by calling her overweight and manly, and even that she was dirty. The fact that she was unmarried was a huge blow against her in that historical period, and at one point he added a male friend who she spent time with to his story, implying sexual uncleanliness as well.

Unfortunately, his version is also the only one that was told, as no one asked Mallon for her side of the story. All we have are legal documents outlining why she believed she should be freed from quarantine and a few interviews that reporters somewhat dubiously claim to have conducted with her.

She was blamed for outbreaks she had nothing to do with

Mary Mallon was known as "Typhoid Mary" even during her lifetime, with the nickname first appearing in a 1908 edition of the Journal of the American Medical Association. By the following year, "Typhoid Mary" was writ large in newspaper headlines and remained there until she died, when the headlines announcing her passing again labeled her "Typhoid Mary." Mallon was fully aware of her nickname and hated it with a passion.

The phrase became shorthand for anyone who spread disease. When a carrier was discovered, regardless of what illness was actually present, they were referred to as "another 'Typhoid Mary.'" Any outbreak of typhoid would lead to jokes about how she was involved.

There are plenty of facts about "Typhoid Mary" the average person doesn't know, but decades after her death, even professional historians have misrepresented Mallon's story. A misunderstanding of a source by a historian in the 1960s resulted in her being blamed for sickening 1,300 people with typhoid in Ithaca, New York. While this event did occur before Dr. Soper found and quarantined Mallon, she had no connection to the outbreak. Perhaps even worse, despite her obvious and understandable misunderstanding about what being a healthy carrier meant, some historians started implying that Mallon probably knew she was making people sick and didn't care.